Jupiter’s South Temperate Domain: Origins of new cyclonic features and a change in the cyclic regime, 2019-2024

- 1British Astronomical Association, London, UK (jrogers11@btinternet.com)

- 2Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, AZ, USA

- 3Independent scholar, Stuttgart, Germany

- 4Jet Propulsion Lab, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA

- 5JUPOS team

Summary

Long-term observations by amateur astronomers show that Jupiter’s major domains commonly show cyclic phenomena repeated for several decades, but which can then switch to a different mode of activity [ref.1]. Now these cycles can be characterised thoroughly by modern amateur imaging, complemented by spacecraft images which provide very-high-resolution images of the component features. This is exemplified by the South Temperate Belt (STB), which showed a consistent cyclic pattern of disturbances from 1998-2018, in which new structured sectors of STB would arise preceding oval BA and drift eastward and expand, eventually catching up with oval BA from the following side. From 2019-20 onwards, the style of the disturbances has changed although many consistent aspects remain. Here, we describe the origins of new cyclonic spots preceding Oval BA, similar to previous examples but observed closely by JunoCam. These provide well-studied models for the origins and metamorphoses of cyclonic spots not only in this domain but also in others. We also describe how the new spots have developed into structured segments, showing variations on the previous theme, and resulting in the revival of a dark STB around much of the circumference in a way not seen since the mid-1990s.

Introduction: The cyclic behaviour (1998-2018)

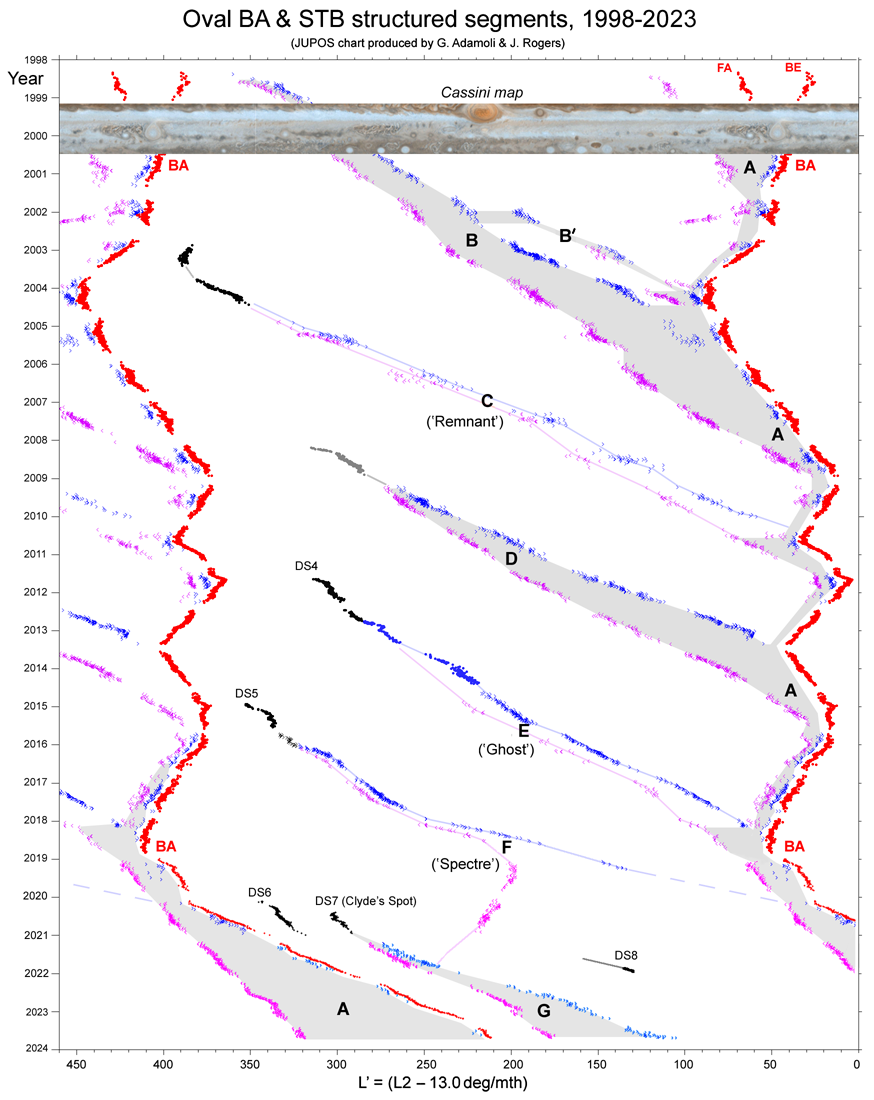

The merger of three large white ovals in 1998 and 2000 left only a single large anticyclonic oval, called BA. Major cyclonic features are ‘structured sectors’ of STB, separated by largely undisturbed sectors, and there are always between two and four of them. One is always a dark sector of STB following BA (STB Segment A), of variable length and activity. Each additional structured sector arose tens of degrees preceding BA, first seen as a small dark spot, then developed in one of two ways: either it would expand as a dark turbulent STB segment, or it would change from dark through reddish to white and then expand as a pale, quiescent loop. In either case, the new structured sector would drift eastward faster than BA and therefore eventually, after several years, having become tens of degrees long, it would collide with dark STB Segment A following BA. This collision caused vigorous activity (including, in two cases, a sudden convective outburst that transformed the formerly quiescent structured segment into a turbulent dark segment); and soon it would merge with Segment A, and emit streams of dark spots eastward (in the STBn jet) and westward. The reinvigorated Segment A would then shrink down towards BA again over one or more years.

All this is summarised in Figure 1 & Ref.2. There were five repeats of this cycle, creating structured segments designated sequentially from B to F.

Shift to a new regime

In 2019 there was just one structured sector apart from Segment A: a long pale loop called the ‘STB Spectre’ (Segment F). Unlike previous examples, it grew extremely long, so its following end was no longer approaching BA; and when its preceding end arrived at Segment A, in early 2020, it did not transform internally. Instead, Segment A itself grew more active and longer as it accelerated BA eastward, and initiated the usual streams of dark spots eastward and westward. The STB Spectre itself became unrecognisable.

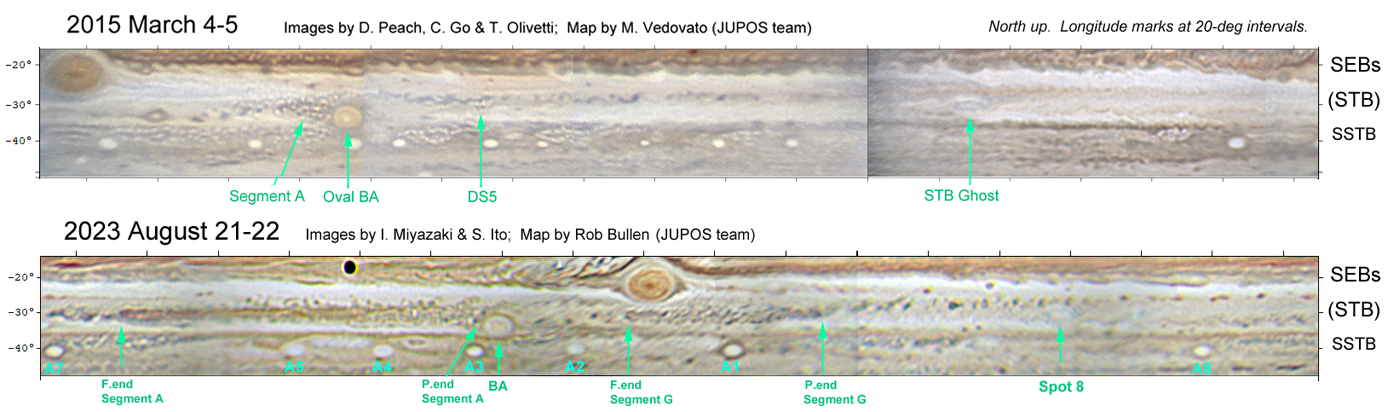

Meanwhile, we were expecting one or more new cyclonic spot(s) to arise some way preceding BA to initiate the next structured sector. This eventually happened in 2020, with appearance of two dark spots which we named spots 6 and 7. Spot 7 would become the more important: a sudden convective outburst within it created “Clyde’s Spot”, a turbulent feature which has expanded continually from that time to become the new turbulent, dark STB Segment G [refs. 3&4]. As oval BA had accelerated to similar speed, the longitudinal cycle of successive segments has been broken. Instead, the expanding Segments A and G, and the streams of dark spots emitted from both of them, have led to re-creation of a visibly dark STB around much of the circumference (Figure 2).

Evolution of cyclonic spots

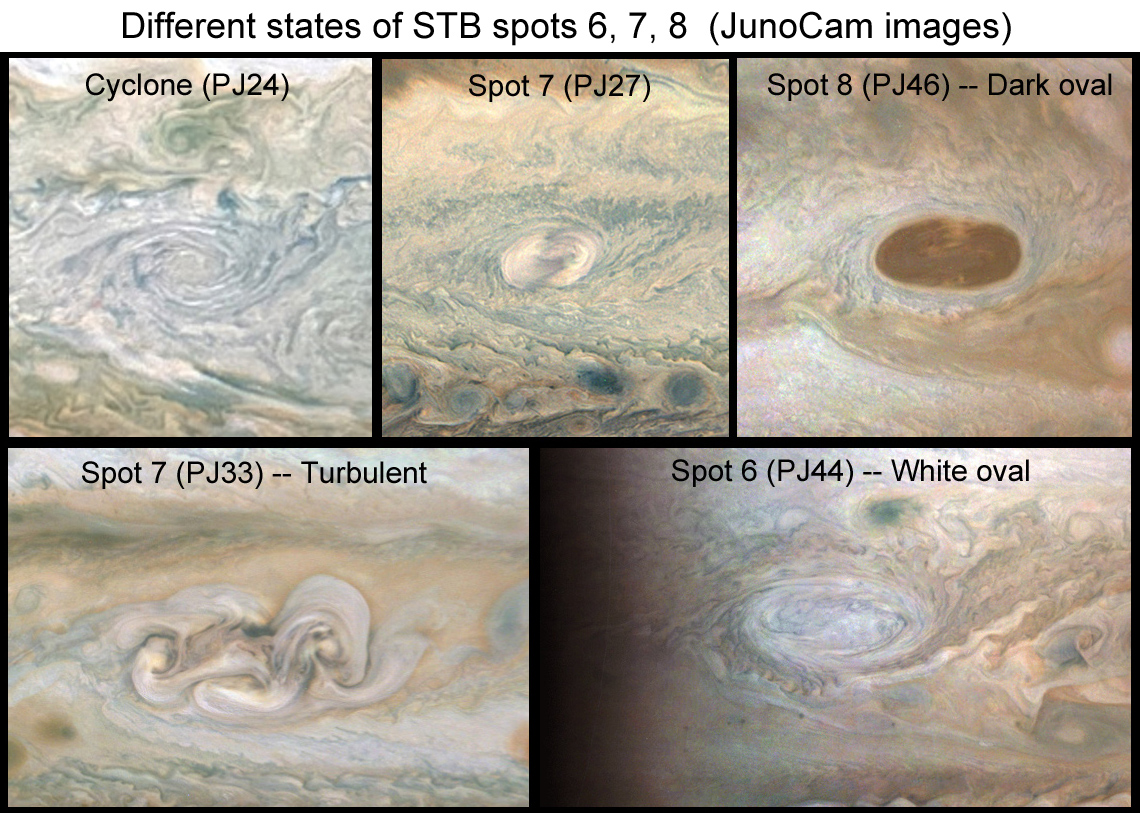

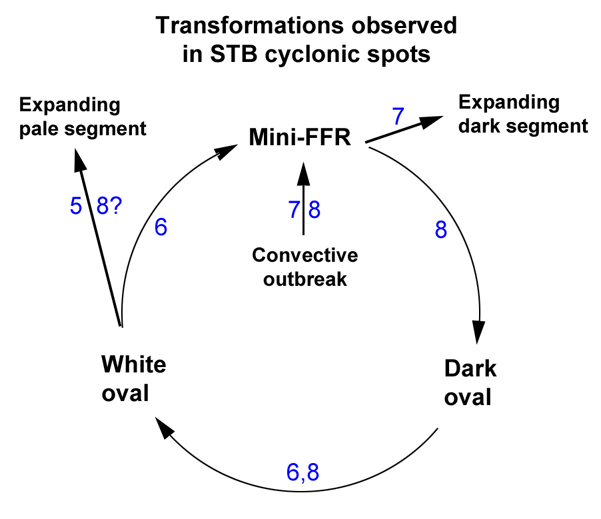

Spots 6 and 7, and a new Spot 8 which appeared in 2021, have all undergone various transformations during their lifetimes, intermittently observed close up by JunoCam. Even before 2020, JunoCam had revealed several small, pale cyclones in the whitened STB latitudes p. BA, and spots 6, 7, and 8 developed by transformation of these cyclones [ref.4]. Subsequently, they transformed variously between three canonical types of cyclonic circulation (e.g. Figure 3): dark oval (“mini-barge”); white oval (which may expand); and turbulent patch (“mini-FFR”, which may also expand, to become a dark STB segment). Figure 4 summarises the metamorphoses of these three spots.

The same three types of cyclonic circulation are common in other domains, with minor variations. In the S2 domain, where they are often longer oblongs, we have documented how each type can change into any other type [see our EPSC abstract in the OPS2 session].

Acknowledgements:

Some of this research was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (80NM0018D0004).

Details of the observations are posted in regular reports on the JunoCam and BAA websites:

https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu/junocam; https://britastro.org/sections/jupiter

References:

1. J.H. Rogers, The Giant Planet Jupiter. CUP (1995).

2. J. Rogers et al., BAA reports on Jupiter’s South Temperate domain, 1991-1999-2012-2015-2018: https://britastro.org/node/17283 & refs. therein.

3. C. Foster et al., EPSC Abstracts (2020) no.196 & (2021) no.121.

4. R. Hueso et al., ‘Convective storms in closed cyclones in Jupiter’s South Temperate Belt: I. Observations.’ Icarus 380, 114994 (2022).

Figure 1:

Figure 2:

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

How to cite: Rogers, J., Hansen, C., Eichstädt, G., Orton, G., Momary, T., Adamoli, G., Bullen, R., Foster, C., Jacquesson, M., Vedovato, M., and Mettig, H.-J.: Jupiter’s South Temperate Domain: Origins of new cyclonic features and a change in the cyclic regime, 2019-2024, Europlanet Science Congress 2024, Berlin, Germany, 8–13 Sep 2024, EPSC2024-362, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-362, 2024.