- 1CSIRO, Space & Astronomy, Australia

- 2Sydney Institute for Astronomy, University of Sydney, Australia

- 3Freelance, Australia

- 4Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Japan

- 5Australian National University, Australia

- 6CSIRO, Environment, Australia

- 7Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Alaska Anchorage, Alaska

There is no denying that we are living in a state of climate emergency, and yet across both astronomy and globally, the shift away from “business as usual” towards more sustainable practices seems too slow to realise meaningful change on the required timescale. One of the key challenges in the current situation is knowing exactly what we can do to improve things, or what actions can be taken at different scales ranging from individuals to institutions. As has been previously discussed by Stevens et al. 2020, carbon emissions associated with travel are a large fraction of the total emissions produced by astronomers in our professional capacity, and still we are yet to see a significant change in physical travel for meetings, conferences or collaboration (e.g. Figure 1).

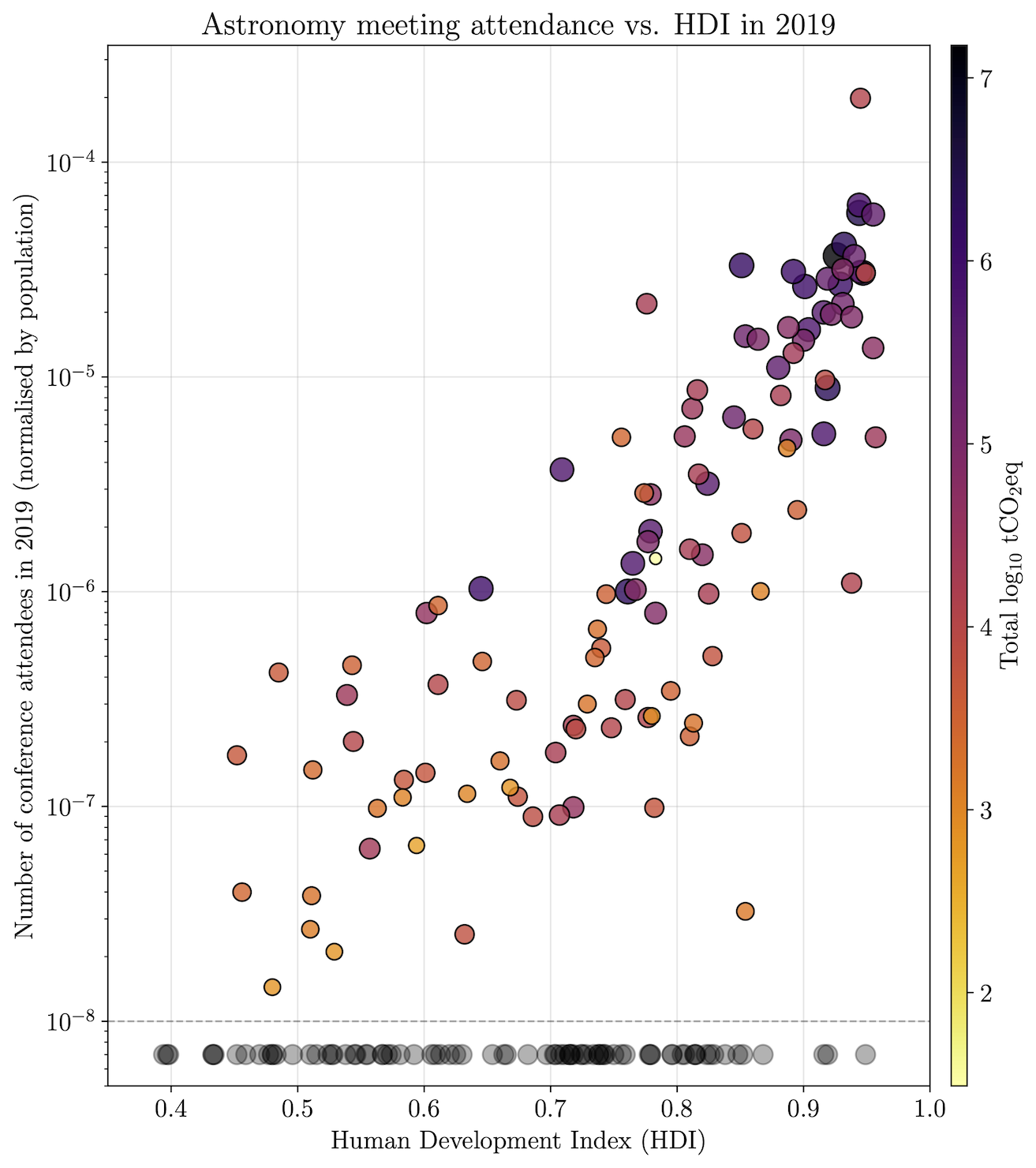

Our work as part of “The Future of Meetings” (TFOM) community of practice (consisting of people working in the field of astronomy, professional scientists in other disciplines such as climate science, computational chemistry and archaeology, and broader academic and industry contacts) has focused especially on the gains that can be made by the widespread adoption of effective online and hybrid meeting practices. The benefits of embracing online interaction are huge when considering sustainability and the climate, as the successful enacting of online meetings can significantly reduce the need to travel physically, whether that travel be locally to a workplace, nationally for collaborations and meetings or internationally for large-scale conferences. These benefits carry through to other important aspects of improving astronomy, such as increasing accessibility where barriers exist for in-person travel and enhancing inclusivity for groups that have been historically excluded from traditional meeting practices. It is clear when we measure attendance at meetings and conferences (Figure 2) that the attendee population, and their associated carbon emissions, are dominated by the most wealthy and privileged countries.

Astronomy especially can provide a unique voice in the global conversation about the future of meetings, interaction and distributed work, considering additionally the significant carbon demands of our field in terms of travel, observatory operations and computing. Our work by default focuses on looking outwards into the Universe, and in placing our experience on Earth in the bigger picture of what is happening beyond our planet. We are a field with a long history of innovative global collaboration, with tendencies towards early adoption of new technologies as well as collaborative teams that are distributed by their nature either across countries or continents. As a field, we have also taken significant steps already towards tangibly increasing the diversity of contributions to advancing research in astronomy, moving beyond the concept of acknowledging the challenges and focusing on measurable solutions.

The recent publication of “Climate Change for Astronomers” (Figure 3), edited by Travis Rector, focuses on addressing the climate crisis specifically from the astronomy perspective. The final chapter in this book was contributed by our group, with a focus on practical advice and examples that are intended to give people a sense of what can be done to measurably improve the sustainability of our meetings and interactions, from the individual through to institutional and international practices.

In this presentation, we will give an overview of the contents of the chapter and provide additional context to it for those interested to make use of our advice. We will cover: 1) introduction to TFOM and context around our general work, 2) the history and evolution of meetings in astronomy, 3) motivations for meetings and interactions in astronomy, 4) the benefits of online interaction in improving our “business as usual” practices in astronomy, 5) the role of technology in facilitating these improvements, 6) suggestions for next steps, 7) examples of common concerns about online and hybrid meetings and how to address them, 8) example case studies of online and hybrid meetings, and 9) looking to the future.

We especially hope to engage with the EPSC community about their experiences in this area and the unique challenges facing this segment of the global astronomy community, and form connections with those in attendance with a look towards the potential for future collaboration in the context of TFOM and ways of tangibly addressing the climate emergency. We firmly believe that online interaction offers immense opportunities for improving both our practices and our experiences in astronomy, and that by embracing these possibilities and the benefits they provide, we can truly go “beyond being there” in a way that also helps preserve our unique place in the Universe for future generations.

Figures

Figure 1: Indicative conference formats in astronomy as a function of time, based on meetings recorded by the Canadian Astronomy Data Centre. The format of a meeting was determined based on referring to the location provided for each meeting (where "online" aims to capture both online-only and hybrid meetings), and thus is likely to be incomplete in terms of meetings which provide hybrid access (if not indicated by the location text). Similarly, the measurement of cancelled meetings is a lower limit since it is likely many cancelled meetings do not feed back into the CADC listing. 2024 is incomplete given it is a year still in progress. While we saw a significant increase in meetings providing online access around the COVID-19 pandemic, this trend has reversed almost completely as of 2024. Credit: Vanessa Moss, for this abstract.

Figure 2: Number of conference attendees at astronomy conferences, normalised by country population, in 2019 as a function of Human Development Index (HDI) for a given country. The colour scale and size of the markers show the total amount of travel emissions for each country. Circles below the dashed line represent the distribution of the HDI for countries with no attendance at astronomy/astrophysics meetings in 2019. Credit: Gokus et al. 2024 (Figure 7).

Figure 3: Cover of the recently published IOP Astronomy book “Climate Change for Astronomers”, edited by Travis Rector. The TFOM community contributed Chapter 19 to this book: “The Future of Meetings”. Credit: Rector et al. 2024.

How to cite: Moss, V., Rees, G., Hotan, A., Kerrison, E., Tasker, E., Kobayashi, R., Trenham, C., Ekers, R., and Rector, T.: The Future of Meetings: How can we adjust our practices to meet sustainably yet meaningfully?, Europlanet Science Congress 2024, Berlin, Germany, 8–13 Sep 2024, EPSC2024-705, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-705, 2024.