On 6th December 2020, a capsule parachuted down into the Australian desert. Inside the sealed chamber were grains collected from asteroid Ryugu: a type of carbonaceous asteroid whose minerals might offer clues as to how the Earth became habitable.

The sample had been collected by the Japanese Hayabusa2 mission during a six year round-trip to the asteroid, breaking a series of world records in both science and engineering. The spacecraft’s journey had been followed from around the world as Hayabusa2’s cameras picked out the asteroid surface for the first time, followed by deployment of rovers and the European-developed MASCOT lander to the asteroid surface, and then two challenging touchdowns to collect material from the boulder-strewn landscape. A continual stream of news and images had been shared via the mission website and social media feeds, with the sample collections and final Earth return broadcast in live events. But now, there was a problem.

To avoid contamination from the Earth environment, the Japanese team had moved rapidly to locate the sample capsule and bring this to the extraterrestrial sample curation facility at the JAXA Sagamihara Campus within 60 hours. The capsule was opened in vacuum conditions, before being transferred to analysis chambers filled with unreactive pure nitrogen gas. Over the next six months, the sample was carefully catalogued so that scientists could propose experiments that would reveal more about the recovered grains. The asteroid grains would therefore travel around the world. But they would always be handled inside scientific clean facilities where few people would ever set foot. To almost everyone in the world, the mission that had filled the news for the last six years would disappear.

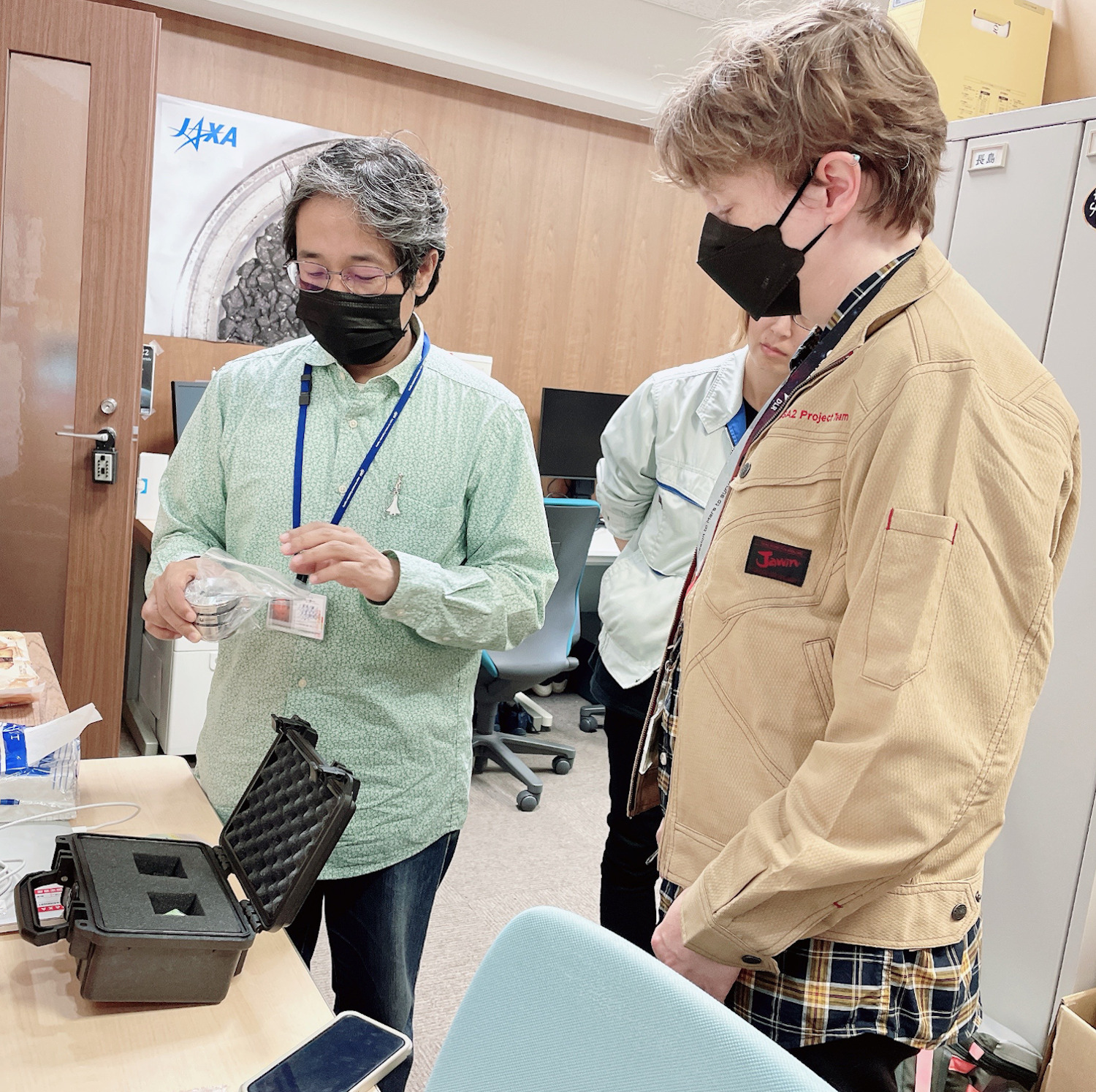

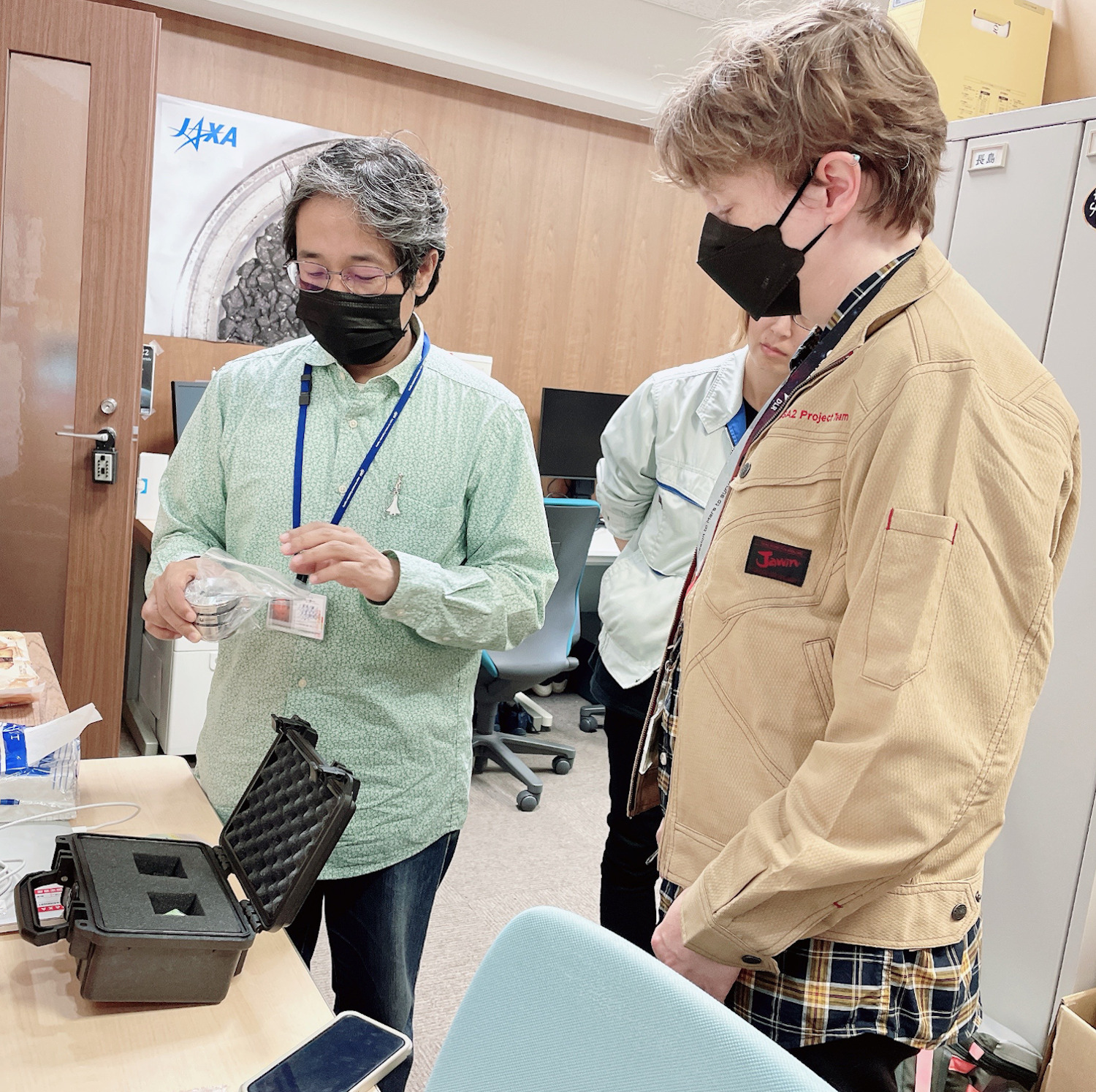

Preparing the asteroid grains for transport (JAXA).

This was both an outreach and scientific concern. After opening the sample capsule, 60% of the asteroid grains had been put aside from the grains that would be distributed for scientific study. This part of the sample is being saved for future analysis, stored for the next generation of scientists who would have new questions to ask with newly developed scientific instruments and techniques. But if the current sample analysis is performed only behind closed doors, with results emerging purely in technical journal papers, how do you inspire new scientists to join the investigation?

For this reason, the curation team extracted a small number of asteroid grains from the main sample. These would not be used for scientific analysis, but be sent to museums for public display. While little could be discerned by eye from these tiny grains, they represented the result of the Hayabusa2 mission, and the beginning of a new scientific story of what we could learn about the start of our own planet.

It is a scientific story that applies to all humans that inhabit this amazing habitable world. The asteroid grains should therefore be displayed not only in Japan, but reach an international audience.

Then the JAXA team were approached by the Science Museum in London, and shortly afterwards, by Cité de l’espace in Toulouse. Both were major museums that drew large crowds every year from all over the world. The museum teams were also experienced in curation and had displayed lunar samples from the Apollo missions, guaranteeing that the fragile asteroid grains would be properly handled.

At JAXA, we worked with both museums to develop displays that were eye catching, but could showcase such a tiny object. The first question was how the asteroid grains should be stored while on display. One choice was to seal the grain in a small disc of resin. This allows the grain to be displayed sideways, which was easier to view inside a display case. However, the resin did add an extra barrier between your eye and the grain. The second choice was to place the asteroid grain inside a facility-to-facility transfer container (FFTC) that was used when transporting the sample between laboratories. The FFTC was quite an interesting object to display, but it did have to be kept almost horizontal, or the asteroid grain would slide to the edge of the container and might fragment. In the end, both museums selected the FFTC, with Cité de l’espace requesting a second grain that could be displayed in resin.

Left: the exhibit at the Science museum (Science Museum Group). Right: the exhibit at Cité de l'espace (Cité de l'espace).

The second challenge was visibility. The Science Museum opted to place the asteroid grain inside the FFTC near the floor of a tall display case, with a mirror to reflect the inside of the FFTC to higher heights. This allowed good visibility for children and wheelchair users, as well as standing adults. Cité de l’espace projected an image of the grain through a microscope onto a screen to create an easily examined picture. We also created 3D printed models of the displayed grains that were enlarged so that the shape of the grain could be easily seen.

The asteroid grains were carried by hand from Japan to Europe last summer. Customs forms had to be carefully prepared to indicate that the asteroid grain was a loan, and did not represent the exportation of soil. In September, the first international public exhibits of the asteroid Ryugu grains opened in London and Toulouse! Events held at both museums welcomed JAXA and scientists who had worked on the mission to public talks and panel discussions. The exhibit in London is open until January 2025, after which the asteroid grain will move to a new display location also in the UK. The Cité de l’espace exhibit will be open for at least one more year. Ryugu, we’re so excited to see you in Europe!