- 1Northern Arizona University, Department of Astronomy and Planetary Science, United States of America (anm744@nau.edu)

- 2University of Victoria

- 3Herzberg Astronomy and Astrophysics Research Centre

- 4Space Telescope Science Institute

- 5University of Pennsylvania

- 6Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

- 7Lowell Observatory

- 8Universidad de Chile

- 9University of Michigan

Introduction: Trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) exhibit a distinct bifurcation in surface colors that reflects differences in dynamical histories. Cold classical TNOs occupy low‑inclination, near‑circular orbits beyond Neptune and display extremely red optical to near-infrared colors, consistent across a wide size range down to ~40 km [1-4]. New Horizons’ close‑up study of Arrokoth confirmed this trend and revealed a low crater density, suggesting minimal collisional resurfacing [5,6]. Dynamically excited TNOs on resonant, scattered, and detached orbits span a broad range of color from neutral to red [7,8]. As these bodies evolve inward into Centaurs and Jupiter‑family comets, solar heating and higher‑velocity impacts diversify their surfaces [9, 10].

A key question remains whether the smallest cold classicals with diameters less than 20 km retain primordial surface properties, or if frequent collisions lead to spectral neutralization or bluing. Our parallel program uses JWST NIRCam imaging to probe the size distribution of faint TNOs down to ~10 km and HST ACS+WFC3 observations to characterize color diversity at these scales. These data allow us to test whether collisional evolution or preservation of primordial material dominates surface color evolution in the cold classical belt.

Observations: JWST Cycle 1 program #1568 conducted a pencil-beam survey from January 24 to February 4, 2023 using NIRCam filters F150W2 and F322W2. A 20-tile mosaic, centered at 13h RA and –10° Dec, targeted objects between 42-48 AU. Observations at three epochs separated by ~5 days allowed for detections of objects as small as ~10 km.

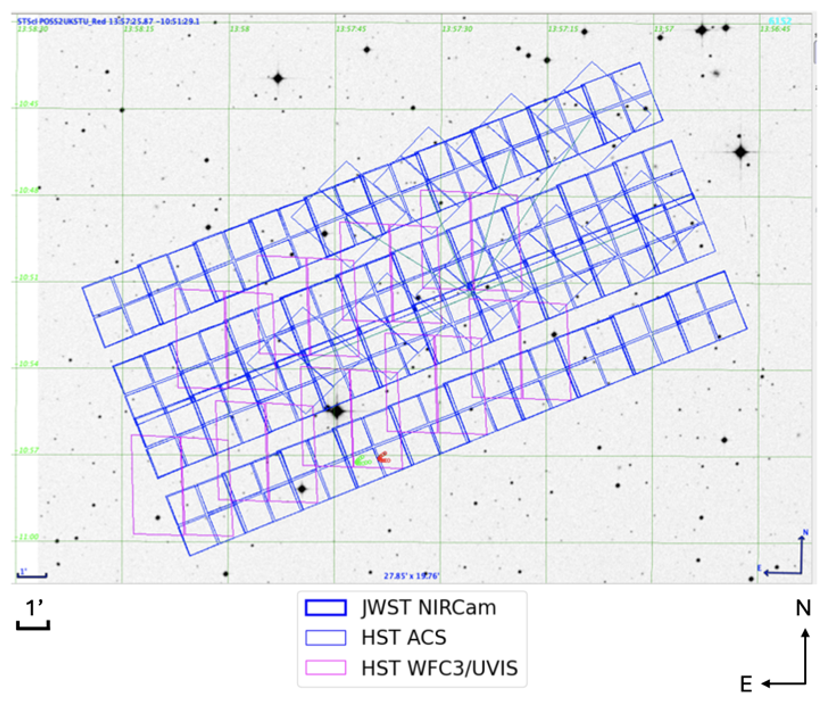

Simultaneously, HST Cycle 29 program #16720 ran from January 24 to February 3, 2023 using ACS filter F814W and WFC3/UVIS filter F350LP. Nine configurations aligned with the JWST footprint were each observed for 11 orbits. Due to differences in pointing constraints, only a subset of JWST discoveries overlap with HST coverage. Figure 1 shows the footprint of both observatories. A known TNO, 2015 GK56, was purposefully placed into both observations to test our recovery pipelines and can also be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Observational footprints of JWST NIRCam (bold blue) and HST ACS (blue) and WFC3/UVIS (magenta) at 13h RA and -10° Dec. The tracks of 2015 GK56 can be seen in green and red.

Analysis: We initially used aperture photometry for objects visible in single exposures, generating preliminary lightcurves via sinusoidal fitting. Colors were calculated from the mean magnitude difference of HST and JWST. Trailed PSF photometry is now being applied to all objects intersecting the HST fields to account for motion blur in the ~1200 s exposures.

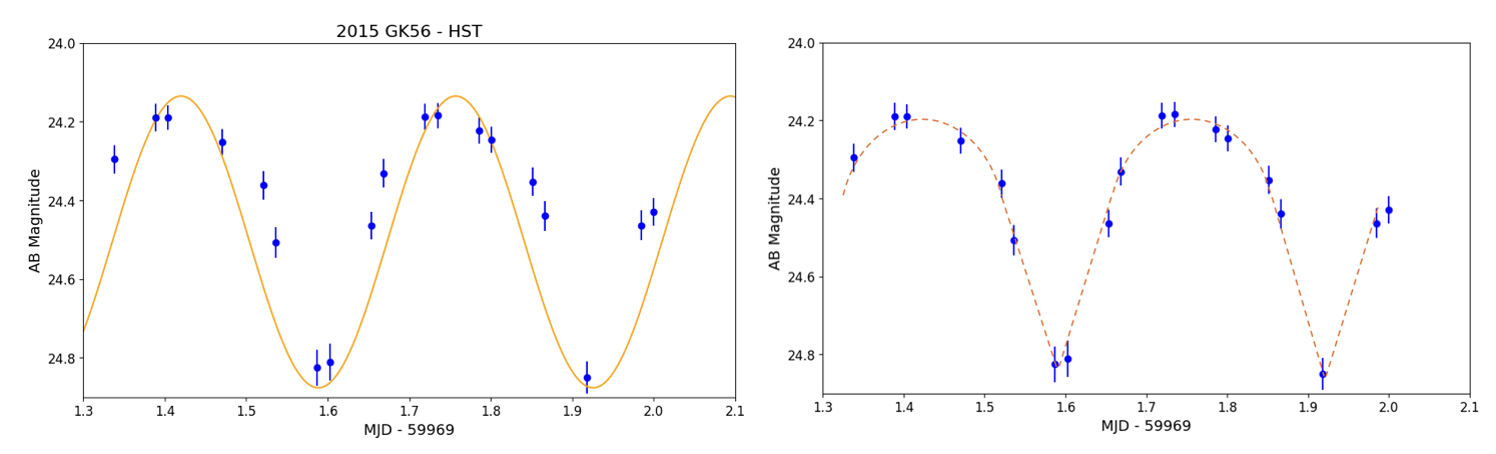

Preliminary Results: TNO 2015 GK56 was recovered in both JWST and HST data. Preliminary lightcurve fitting yields a ~16-hour rotation period and 0.7 mag lightcurve amplitude (Figure 2). The “V-shaped” troughs and inverted “U-shaped” peaks match the signature of a contact binary [11]. Interestingly, its color is more neutral than expected for a cold classical.

Figure 2. HST ACS F814W preliminary lightcurve of 2015 GK56. Blue points show single-epoch photometry with a best-fit curve (solid orange line, left) and the right panel demonstrating the pronounced V-shaped minima and inverted U-shaped maxima that are characteristic of a contact binary.

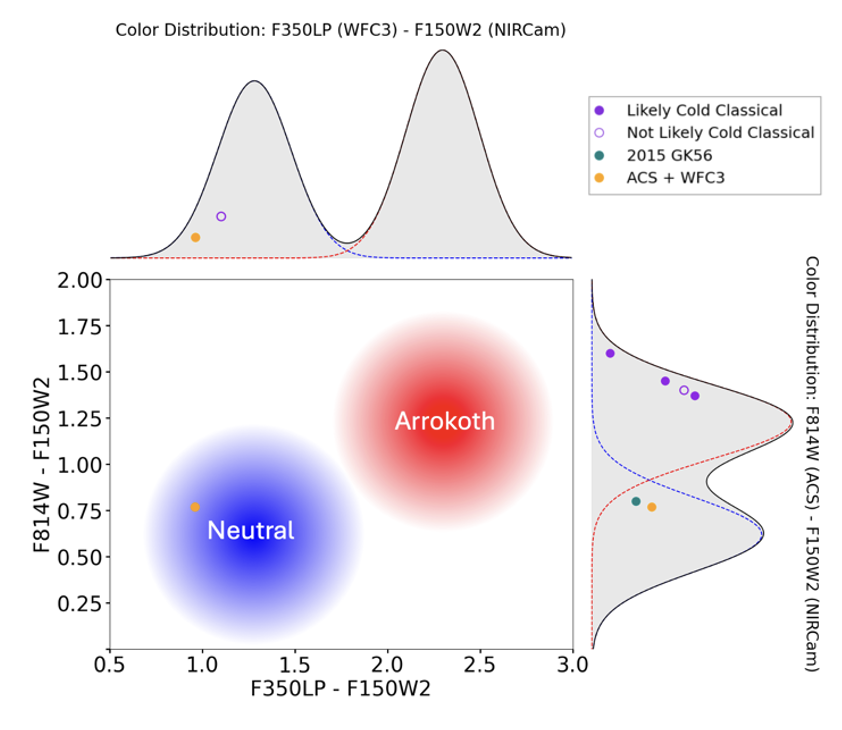

Figure 3 shows a preliminary color-color diagram for objects detected in both JWST and HST. These results combine data from HST’s ACS/F814 and WFC3/F350LP filters with JWST’s NIRCam shot-wavelength (SW, F150W2) filter. All confirmed TNO detections have been observed in both SW and long-wavelength (LW, F322W2) filters, where we have SW/LW color information for each. However, only preliminary photometry from F150W2 is included in this analysis. Additionally, only two TNOs that currently have detections in the F350LP filter. Their distribution reveals a range of surface colors and is consistent with Gaussian-like color trends reported in [9].

Figure 3. Preliminary color-color diagram for TNOs detected in both JWST and HST. The central panel shows color indices (F350LP-F150W2) and (F814W-F150W2) for objects visible in single-exposure data. Color distributions for each filter combination are seen along the top and right axes. The red shaded region marks colors expected for a red spectrum based on Arrokoth, while the blue region corresponds to a neutral, flat spectrum. Error bars are not shown, as these are preliminary measurements. Typical uncertainties are estimated to be ± 0.1 magnitudes.

Future Work: Ongoing efforts include completing trailed PSF photometry for all ACS-detected objects and finalizing a model for the WFC3/F350LP filter. These refinements will improve our photometric accuracy and expand the sample of TNOs with reliable color measurements.

We will compare our measured color distributions to previously published photometry and spectra of TNOs to investigate whether small objects follow similar surface composition trends. We will explore correlations between color and other physical and orbital properties, including size, inclination, and dynamical classification.

In parallel, we will measure lightcurves from the PSF photometry to better characterize features across the sample such as rotational periods, amplitudes, and shapes. Collectively, this work will extend previous color surveys into a fainter regime and smaller size range, helping to determine whether small cold classical TNOs preserve primordial surfaces or have been modified by collisional and dynamical evolution over time.

References: [1] Tegler S. C. and Romanishin W. (2000) Nature, 407, 979. [2] Benecchi S. D. et al. (2019) Icarus, 334, 22. [3] Pike R. E. et al. (2017) Astron. J., 154, 101. [4] Fraser W. C. et al. (2023) Planet. Sci. J., 4, 80. [5] Stern A. et al. (2019) Science, 364, aaw977. [6] Grundy W. M. et al. (2020) Science, 367, aay3705. [7] Levison H. F. et al. (2008) Icarus, 196, 258. [8] Marsset M. et al. (2019) Astron. J., 157, 94. [9] Tegler S.C. et al. (2016) Astron. J., 152, 210. [10] Jewitt D. (2015) Astron. J., 150, 201. [11] Thirourin A. and Sheppard S. S. (2019) Astron J., 157, 228

How to cite: Morgan, A., Eduardo, M., Trilling, D., Fraser, W., Stansberry, J., Bernstein, G., Hilbert, B., Holman, M., Grundy, W., Tegler, S., Fuentes, C., and Napier, K.: Joint JWST and HST Deep Imaging to Characterize Cold Classical TNO Colors, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1035, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1035, 2025.