SB5

Physical properties and composition of TNOs and Centaurs

Convener:

Csaba Kiss

|

Co-conveners:

Thomas Müller,

Silvia Protopapa,

Estela Fernández-Valenzuela,

John Stansberry

Orals WED-OB2

|

Wed, 10 Sep, 09:30–10:30 (EEST) Room Earth (Veranda 2)

Orals WED-OB3

|

Wed, 10 Sep, 11:00–12:30 (EEST) Room Earth (Veranda 2)

Orals WED-OB5

|

Wed, 10 Sep, 15:00–16:00 (EEST) Room Earth (Veranda 2)

Orals WED-OB6

|

Wed, 10 Sep, 16:30–18:30 (EEST) Room Earth (Veranda 2)

Posters TUE-POS

|

Attendance Tue, 09 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Tue, 09 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Finlandia Hall foyer, F138–149

Wed, 09:30

Wed, 11:00

Wed, 15:00

Wed, 16:30

Tue, 18:00

Session assets

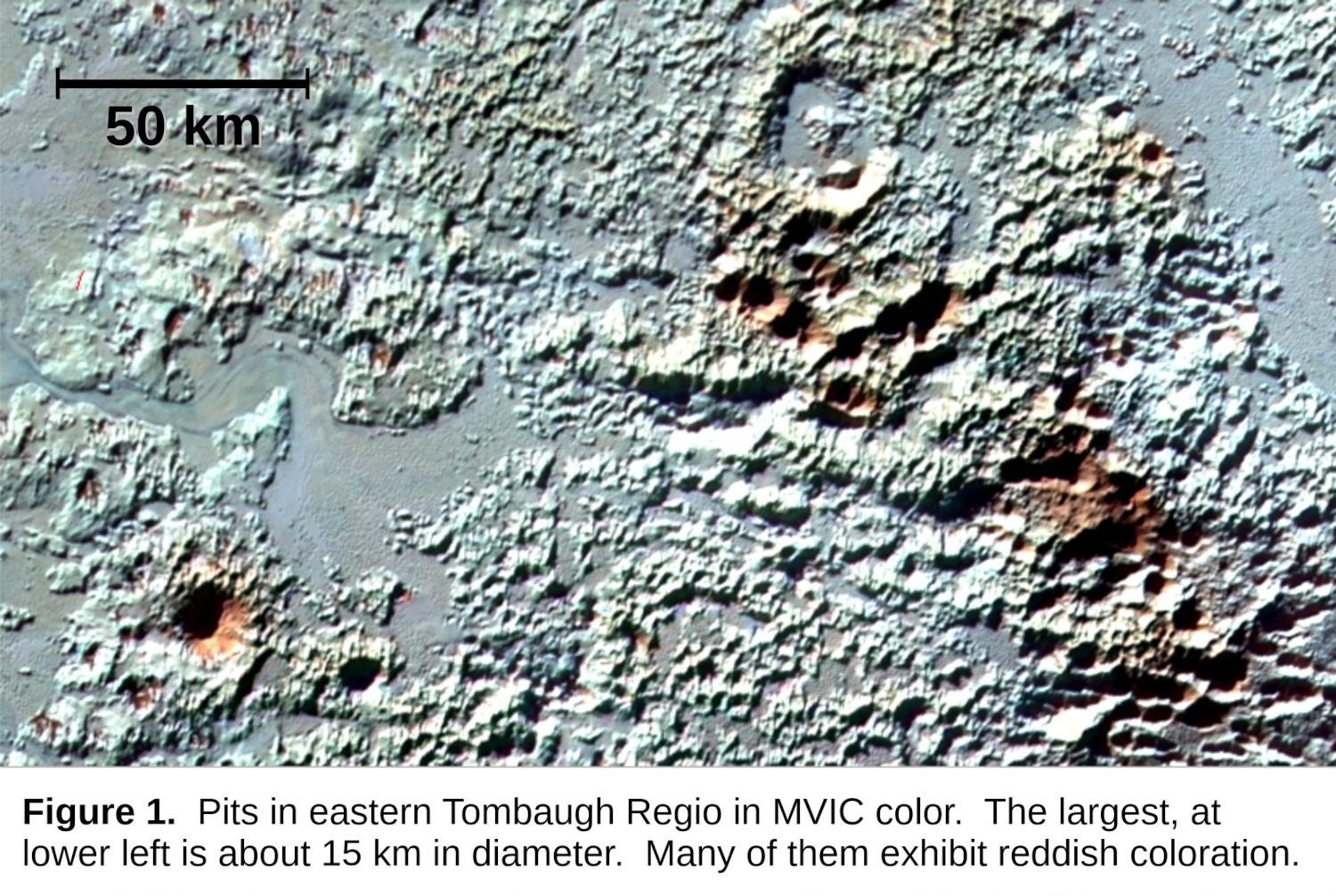

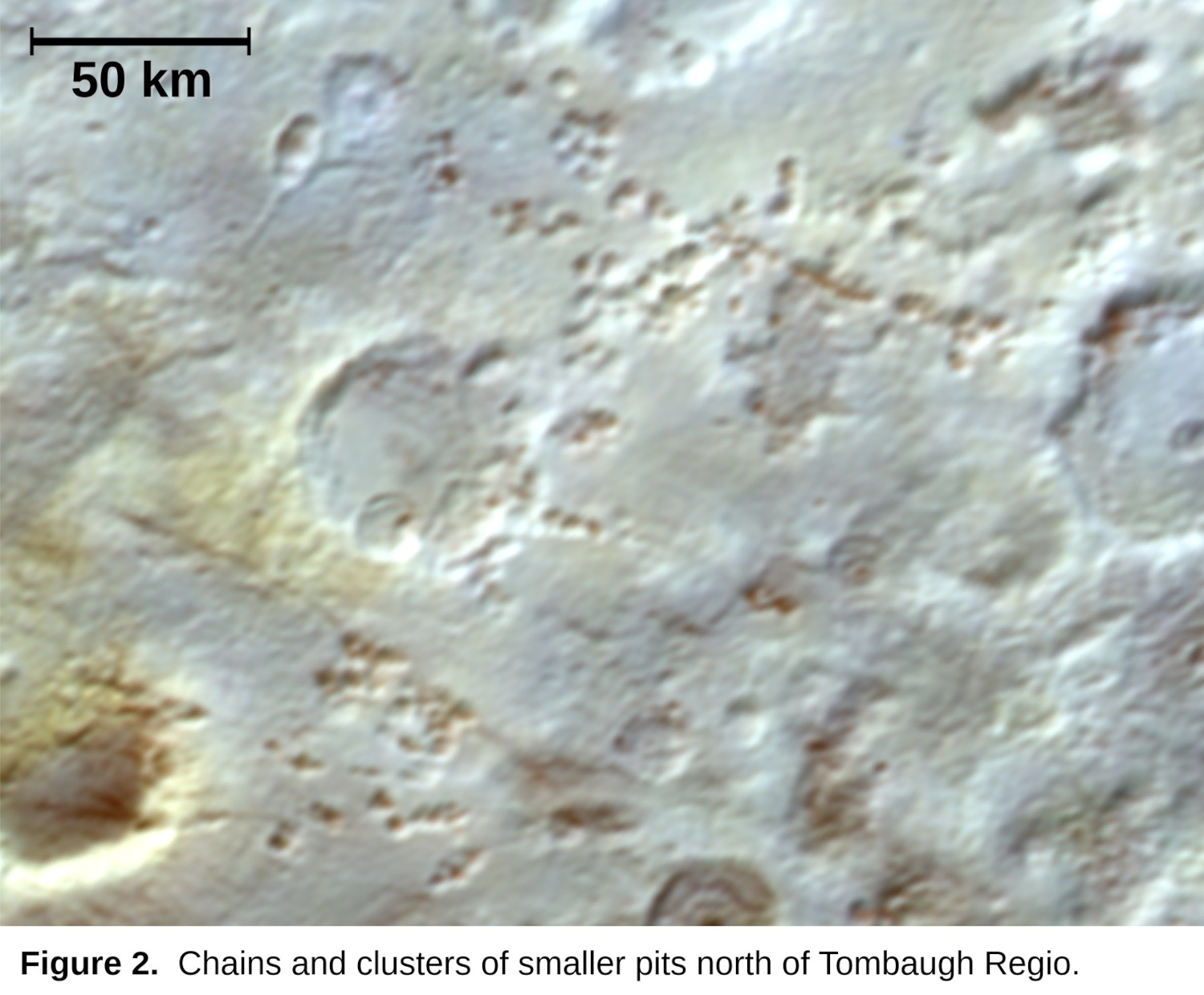

Pluto / New Horizons

09:30–09:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-184

|

On-site presentation

09:42–09:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-862

|

On-site presentation

09:54–10:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-791

|

On-site presentation

Rings

10:06–10:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1768

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

Occultations

11:00–11:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-380

|

Virtual presentation

11:12–11:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-252

|

On-site presentation

Physical properties of TNO’s satellites from stellar occultations

(withdrawn)

11:24–11:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-254

|

On-site presentation

11:36–11:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-345

|

On-site presentation

Binaries

11:48–12:00

|

EPSC-DPS2025-339

|

ECP

|

Virtual presentation

12:00–12:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-905

|

On-site presentation

12:12–12:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-225

|

On-site presentation

12:24–12:30

Discussion

Discovery and photometric monitoring

15:00–15:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1006

|

On-site presentation

15:12–15:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1418

|

On-site presentation

15:24–15:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-38

|

On-site presentation

15:36–15:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-771

|

On-site presentation

15:48–16:00

|

EPSC-DPS2025-450

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

16:30–16:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1230

|

On-site presentation

JWST results

16:54–17:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-848

|

ECP

|

Virtual presentation

17:06–17:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-59

|

On-site presentation

17:18–17:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-459

|

On-site presentation

17:30–17:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-968

|

On-site presentation

17:42–17:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-383

|

On-site presentation

17:54–18:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-424

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

18:06–18:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-16

|

On-site presentation

18:18–18:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1035

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F138

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1053

|

On-site presentation

F139

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1527

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

Multi-epoch stellar occultations by the large trans-Neptunian object (28978) Ixion

(withdrawn after no-show)

F140

|

EPSC-DPS2025-21

|

On-site presentation

F141

|

EPSC-DPS2025-24

|

On-site presentation

F142

|

EPSC-DPS2025-227

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F143

|

EPSC-DPS2025-371

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F144

|

EPSC-DPS2025-539

|

On-site presentation

F145

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1214

|

On-site presentation

TAOS II: The Transneptunian Automated Occultation Survey

(withdrawn after no-show)

F147

|

EPSC-DPS2025-728

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F149

|

EPSC-DPS2025-518

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation