- 1Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado, USA (scot.rafkin@swri.org)

- 2University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA (selizabethdolski@gmail.com)

- 3NASA Ames Research Center, Mountain View, California, United States of America (alison.bridger@sjsu.edu)

1. Introduction and Motivation

Regional to large-scale dust storms are climatologically favored in the Hellas Basin region, especially during the northern fall equinox. The dust storms, while often occurring in the same general season year after year, do not occur repeatedly sol after sol. It follows that the wind stress must cross an initial threshold above which dust lifting occurs and then fall below that threshold in two sols or less. Prior to and after that peak, the wind stress must be below the lifting threshold as the canonical scenario. The most common scenario is for an absence of storms.

The Hellas region exhibits numerous superimposed atmospheric circulations of different spatial and temporal scales: The seasonally-varying large-scale mean meridional (Hadley) circulation; large-scale stationary waves, the ubiquitous large-scale tidal circulations (primarily diurnal and semi-diurnal); traveling/transient eddies primarily associated with large-scale baroclinic instabilities; standing waves within Hellas itself (e.g., basin-wide gyres); and mesoscale direct thermal circulations associated with topographic slopes, ice/ice-free boundaries, and thermal inertia and albedo variations. All these individual circulations sum in non-linear ways to produce the total net circulation in the Hellas region. Except for traveling baroclinic waves, all the other circulations should have nearly repeatable amplitude and phase from sol to sol at a given season. Therefore, these quasi-constant circulations likely are not the source of dust storm genesis since constant amplitude and constant phase circulations are unlikely to add together to exceed the dust lifting threshold.

2. Hypothesis

Prior work suggests that baroclinic storm systems circling along the ice cap edge are an important mechanism for the generation of dust events. Although the baroclinic activity is ubiquitous around Ls 180, only a small number of dust events occur each year. Baroclinic waves typically have a period of several days, but dust lifting in the region is stochastic and not periodic. Therefore, if traveling baroclinic waves are responsible for the dust lifting, only a handful of these systems per year trigger dust lifting events while most of the waves do not. We hypothesize that only special and rare types of baroclinic systems can push the wind stress beyond the lifting threshold. These rare systems, perhaps only one or two per year, explain the stochastic and infrequent nature of dust storms. However, the storms depend on a climatologically strong non-baroclinic background circulation to generate a high surface wind stress condition that is, by itself, below the lifting threshold.

3. Hypothesis Testing Methodology

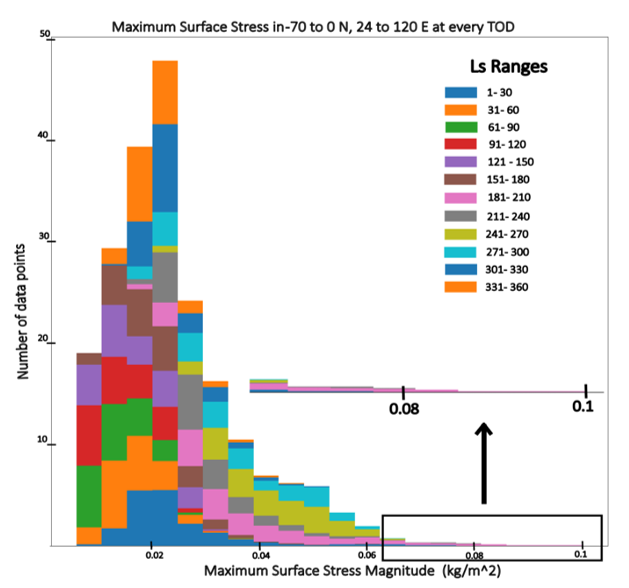

Statistical analysis is performed on 10 years of NASA Ames Mars General Circulation Model output in the Hellas Basin region to identify the most intense surface wind stress events (Figure 1). From this catalog of events, the highest stress events are analyzed to decompose the circulation into separate background and traveling (mostly baroclinic) components and to characterize and correlate baroclinic characteristics with high surface wind stress events.

4. Results

The highest stress events all occur around Ls 180 and are associated with extratropical (baroclinic) storm system. Further synoptic analysis shows that there are three types of systems that are conducive to producing the highest surface wind stress. In each type, the strength and orientation of the high and low pressure systems align to constructively add to the background circulation. These three storm types are rare and are clearly distinguishable from the far more common baroclinic storm systems that regularly evolve and traverse the Hellas region.

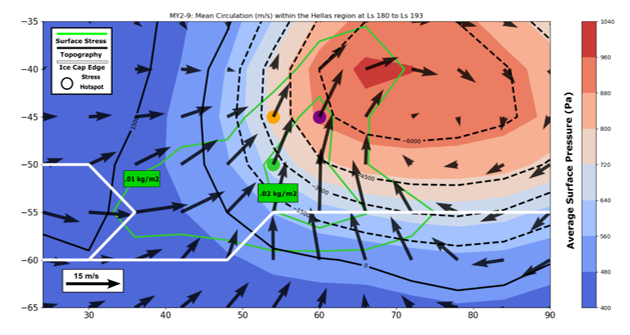

There are shared characteristics of the maximum wind stress events in the model analysis. Maximum stress events consistently occur at 0000 – 0600 LT when downslope flows are strongest. Only one case occurs at 1500 LT. The strongest events also occur in a localized area in southwest Hellas from 45 to 55 S and 54 to 66 E. This region corresponds to the strongest non-baroclinic surface stresses, thus setting the stage for a transient baroclinic eddy to trigger a dust storm (Figure 2). Systems that do not fall into one of the three categories, even though they may be deep and intense baroclinic storms, do not produce the highest wind stresses.

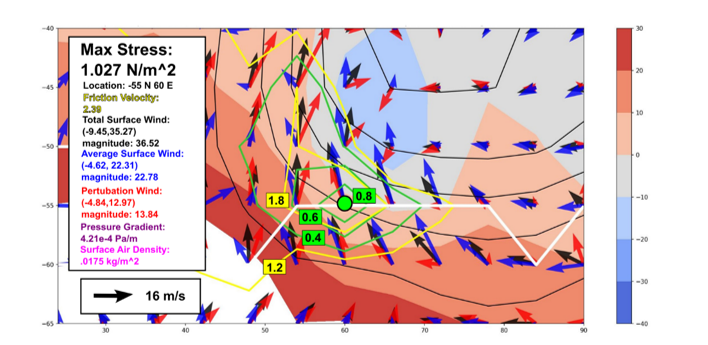

An example of a baroclinic system responsible for the highest stress case in year 3 is shown in Figure 3. This event was produced by a baroclinic low pressure in South Hellas and a strong anticyclone moving from the West into the Western Hellas ridge between latitudes -30 to -50 N. The result was an anomalous pressure gradient perturbation driving strong perturbation winds that aligned with the mean wind. Although large wind speeds are collocated with maximum stress, high speeds are also recorded west of Hellas Basin. However, the lower density at higher elevations reduces the wind stress compared to lower elevations.

The other two types of baroclinic systems have different high/low pressure configurations compared to Figure 3, but all result in an anomalous pressure gradient that drives strong perturbation winds that constructively add to the mean. The vast majority of baroclinic systems, even those with strong pressure gradients, do not align with the background circulation and do not contribute to high stress events. The analysis of the GCM model output is consistent with the hypothesis invoking rare and special baroclinic events as the source of Hellas Basin dust storms near Ls 180.

Figure 1. Histogram of the maximum surface stress events in 10 years of model data within the Hellas Basin region. There are a very small number of high stress events (1 to 2 per year).

Figure 2. The mean Hellas Basin circulation from Ls 180-193. The averaging effectively removes the baroclinic eddy component of the circulation. Surface stress is contoured in green showing a maximum on the southwest slope of Hellas.

Figure 3. An example of a Type 2 event where the baroclinic system occurs at just the right time, in just the right place, at just the right time to produce a strong perturbation pressure gradient and strong winds aligned with the mean circulation.

How to cite: Rafkin, S., Dolski, S., and Kahre, M.: The Association of Hellas Basin Dust Storms to Specific Types of Baroclinic Storm Systems, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1051, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1051, 2025.