Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

TP2

Session assets

The UVI camera onboard the JAXA Akatsuki mission provided long-term series of images of the Venus cloud tops at 283 nm and 365 nm – two wavelength that correspond to the spectral bands of gaseous sulfur dioxide and unknown UV absorber. We used the automated correlation method to track motions of the cloud features and derive wind speed and its variations for two observation intervals one Venusian year each: October 2019 – April 2020 (S07) and April 2022 – September 2022 (S11). The mean zonal velocity derived from 283 nm images at noon is by up to 5 m/s higher than the speed measured at 365 nm. Also the afternoon peak of zonal velocity at 283 nm is shifted towards evening terminator with respect to that measured at 365 nm. Zonal velocity increases with phase angle that implies positive altitude gradient of the wind velocity. This might suggest that the radiation at 283 nm forms in slightly higher layers than that at 365 nm that can explain the difference in velocity measured in two spectral bands.

How to cite: Patsaeva, M., Khatuntsev, I., Ignatiev, N., and Titov, D.: Variability of the cloud top wind speed from the UVI/ Akatsuki imaging at 283 and 365 nm, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-280, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-280, 2025.

Atomic oxygen is important for the photochemistry in the mesosphere and thermosphere of Venus and can be used as tracer for atmospheric dynamics. The altitude range where it predominantly occurs is between 90 km and 130 km with a peak at 100 km – 110 km. Atomic oxygen is mainly generated through photolysis of CO2 on the dayside. From there it is transported to the nightside by the subsolar to antisolar circulation. It accumulates near the antisolar point and recombines to molecular oxygen [1, 2 ,3, 4]. The region between 90 km and 120 km altitude is the transition region from superrotation to subsolar-antisolar flow and is not yet well understood. This is the altitude range probed in this work.

We have detected atomic oxygen on the dayside as well as on the nightside of Venus by measuring its ground-state transition at 4.74 THz (63.2 µm) with the upGREAT (German Receiver for Astronomy at Terahertz Frequencies) heterodyne spectrometer on board SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy) [5]. This is a direct detection in contrast to most past and current detection methods, which are indirect and rely on photochemical models to obtain atomic oxygen concentrations [1, 2]. We have used this transition to determine Doppler shifts and the corresponding wind velocities. Due to the high spectral resolution of the upGREAT heterodyne spectrometer of 0.2 MHz it is possible to measure the speed at which the atomic oxygen is moving towards the observer [6]. The observations were made on Nov. 10, Nov. 11 and Nov. 13 2021. The 2.5-m diameter telescope of SOFIA was pointing at Venus. The telescope provides a diffraction-limited beam with 6.3 arcsec, which is about five times smaller than the apparent diameter of Venus (29 arcsec). The phase of Venus was 42%.

The 4.7-THz channel of upGREAT has seven pixels in a hexagonal pattern separated by 13.6 arcsec. While most of the pixels were on Venus, three pixels were pointing at its limb. At these positions the component of the wind vector which points towards the observer is sufficiently large to be measured with upGREAT. As a reference we take the transition frequency measured by a pixel which points towards the center of the disk of Venus where the wind vector component towards the observer is negligible. The measurements at 45° and 15° north don’t show a wind speed component which is significantly different from zero (13±38 m/s and 2±31 m/s, respectively) while the measurement close to the south pole exhibits a wind speed component of 120±75 m/s. These values are in agreement with the global circulation model (GCM) of Navarro et al. [6].

For those spectra which are not close to the Venus limb, the wind component towards the observer is too small to be measured by upGREAT. However, the variation of column density and temperature of atomic oxygen may serve as an indicator for the dynamics. When comparing the column density determined by upGREAT with the wind velocity provided by the GCM of Navarro et al. [7] it stands out that on the night side the column density peaks at the time between 19 and 20 hour local time where the gradient of the wind speed is strongest (Fig. 1). This might be an indication of an adiabatic flow of an air parcel in the atmosphere of Venus which leads to an increased density when the wind speed drops sharply.

Fig. 1: Column density of atomic oxygen measured by upGREAT (dots, data from [5]) and zonal wind speeds in the region between 90 km and 130 km (from [6]). The dashed line marks the terminator at the surface of Venus. The grey lines are streamlines showing the circulation (from [7]).

References

[1] A. S. Brecht et al., Atomic oxygen distributions in the Venus thermosphere: Comparisons between Venus Express observations and global model simulations. Icarus 217, 759–766 (2012).

[2] L. Soret et al., Atomic oxygen on the Venus nightside: Global distribution deduced from airglow mapping. Icarus 217, 849–855 (2012).

[3] J.-C. Gérard, Aeronomy of the Venus upper atmosphere. in: Space Sci Rev. Venus III edited by B. Bézard et al., Springer Dordrecht (2017).

[4] G. Gilli, et al., Venus upper atmosphere revealed by a GCM: II. Model validation with temperature and density measurements. Icarus 366, 114432 (2021).

[5] H.-W. Hübers et al., Direct detection of atomic oxygen on the dayside and nightside of Venus, Nature Communications, 14:6812 (2023).

[6] C. Risacher et al., The upGREAT dual frequency heterodyne arrays for SOFIA, J. Astron. Instrum. 7, 1840014 (2018).

[7] T. Navarro et al., Venus´ upper atmosphere revealed by a GCM: I. Structure and variability of the circulation, Icarus 366, 114400 (2021).

How to cite: Hübers, H.-W., Graf, U., Güsten, R., Klein, B., Kührt, E., Stutzki, J., and Wiesemeyer, H.: Wind measurements and dynamics in Venus’ upper atmosphere measured by high-resolution terahertz spectroscopy of atomic oxygen, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-918, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-918, 2025.

Introduction

In this study which is a follow-up of [1], we use the most recent version of the ground-to-thermosphere VPCM [2] that includes an ionosphere model, ambipolar diffusion and nitrogen chemistry [3]. This tool allows us to investigate and identify in 3D potential mechanisms responsible for the observed variability in Venus’s atmosphere, in the region between 80 km and 130 km altitude. NO and O2(Δg) airglows, are commonly used to shed light on the global dynamics and circulation patterns above 90 km. Their characteristics are a combination of horizontal, vertical transport and chemical net reactions [1,4].

We performed sensitivity tests of unconstrained parameters (e.g. gravity waves drag and eddy diffusion vertical profile) to evaluate the impact on the dynamical structures, O number density, temperature and O2(Δg) nightglow characteristics. These results depict possible scenarios useful to interpret future EnVision observations of trace compounds in those mesosphere layers currently poorly constrained, and not fully explained by current 3D models.

Motivation of this study

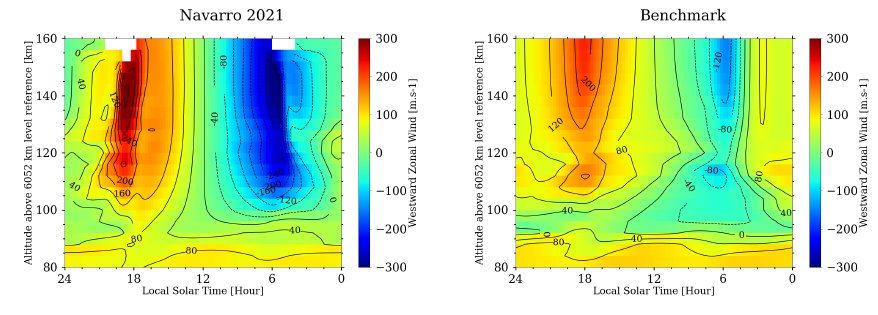

Modeling the region between 80 and 130 km, that marks the transition between superrotation regime in the deep atmosphere and the day-to-night circulation in the thermosphere, is a key step towards understanding the processes governing Venusian dynamics. Recent V-PCM improvements presented in [2] and [3] focused on Venus’s atmosphere above 130 km, and performed a comprehensive validation of model results with PVO, Magellan and VEX observations in the thermosphere and ionosphere. However, those model developments, together with ad-hoc tuning of parameters (see [2] for details) to fit observational data, changed dramatically the global circulation in the transition region in comparison to [1], as illustrated in Fig. 1. It was therefore necessary to carry out a follow-up to the study by [1].

Figure 1: Zonal wind around the equator (latitude 20ºS-20ºN) in local time and altitude predicted by the V-PCM in [1] (leftside) and [2,3] (rightside).

Sensitivity tests of unconstrained parameters of gravity waves

Among the processes studied here, gravity waves are an important source of variability, but they remain extremely poorly constrained by observations. Non-orographic gravity waves are generated in the convective layer of clouds. They will propagate upwards where they will eventually break above 90 km, injecting their momentum into the mesosphere/thermosphere, which will affect wind circulation. In this abstract, we present the cases of two key parameters: the initial amplitude of the GW and the dissipation parameter. In our scheme, the dissipation parameter ensures that the waves are dissipated before reaching the top of the model, and is intended to mimic the dissipation of GW at high altitude.

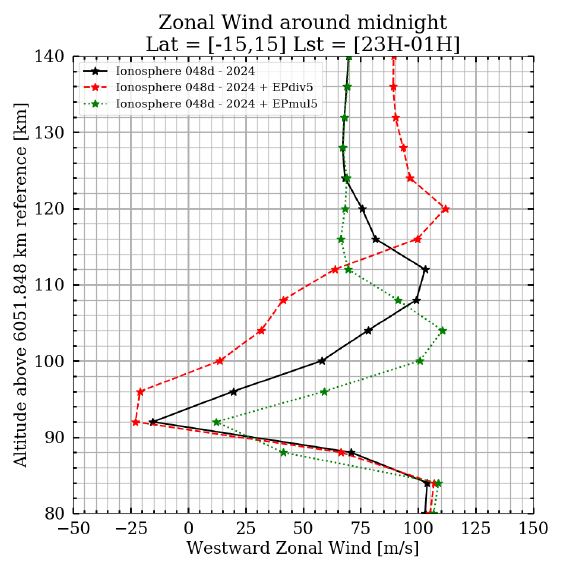

We found that this region (80-130 km) is very sensitive to the unconstrained parameters used in the non-orographic gravity wave parameterization implemented in the V-PCM [2,4]. For instance, the remnant superrotation (~100 m/s) simulated by the V-PCM peaks between 100 and 125 km, depending on the amplitude of non-orographic GW (see Figure 2). Decreasing the initial GW amplitude seems to reduce the retrograde supperrotative component between 90 and 110 km altitude.

Figure 2: Zonal wind profiles around the anti-solar point simulated with the reference V-PCM [2,3] (in black) and varying the maximum EP-flux amplitude in the GW parameterization by a factor x5 (EPmul5) and /5 (EPdiv5).

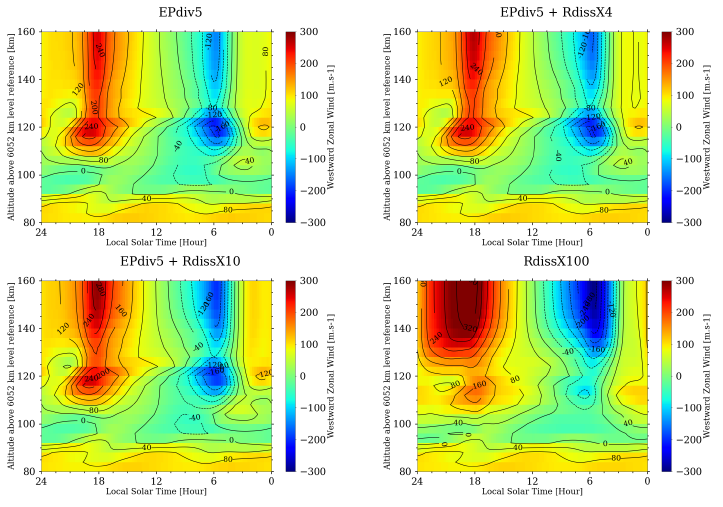

Figure 3 shows simulated zonal wind between 80 and 160 km in the equatorial region as function of local time for several GW configurations. By varying this diffusion parameter by a factor of 0.1 to 100 around our reference value, we see that the larger this parameter, the lower the altitude at which gravity waves begin to dissipate, as expected. However, this explored range of Rdiss values had no effect on the horizontal and vertical positioning of the O2(Δg) emission peak around 100 km. We found, however, a reduction in RSZ remanent around 110 km and larger zonal winds at the terminators with increasing Rdiss (see Fig. 3). This is also associated with an increase in temperature around the antisolar area, linked to an increase in adiabatic heating caused by a stronger downward vertical wind.

Figure 3: Zonal wind in local time and altitude predicted by VPCM tuning GW parameters (Rdiss is the diffusion parameter and EPflux is the amplitude of the non-orographic GW).

Acknowledgements

G.G. and A.M. acknowledge financial support from Junta de Andalucía through the program EMERGIA 2021 (EMC21 00249). AS and LML are funded by the Spanish MCIU, the AEI and EC-FEDER funds under project PID2021-126365NB-C21. IAA-team also acknowledges financial support from the Severo Ochoa grant CEX2021-001131-S funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033. This work was partly funded by project AST22_00001_23 from the European Union- NextGenerationEU, the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the Plan de Recuperación y Resiliencia, the Agencia Estatal Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas and the Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación de la Junta de Andalucía.

References:

[1] Navarro et al. Icarus, 366:114400, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114400

[2] Martinez et al. 2023 Icarus, 389, 115272, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115272

[3] Martinez et al. 2024, Icarus 415, 116035, https://doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116035.

[4] Gilli et al. 2021, Icarus, 366:114432, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114432

How to cite: Martinez, A., Gilli, G., Stolzenbach, A., Navarro, T., Lebonnois, S., González-Galindo, F., Lefevre, F., Streel, N., and Lara, L. M.: Impact of unconstrained parameters on the global dynamics in the “transition region” of Venus atmosphere with the Venus PCM, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1424, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1424, 2025.

Introduction

One of the outstanding questions regarding Venus is whether the planet once retained a significant amount of water. Observations of hydrogen atoms provide critical insights into atmospheric escape processes. Previous studies using Venus Express/SPICAV indicate that the Venusian hydrogen atmosphere consists of two distinct components characterized by different scale heights: a hot component and a cold component [1]. The hot hydrogen component primarily arises from charge exchange reactions and momentum transfer between cold hydrogen atoms and ionospheric ions [2]. Conversely, the cold component originates from the dissociation of sulfuric acid in the lower atmosphere. It is well known that, due to the absence of an intrinsic magnetic field, Venusian atmosphere interacts directly with the solar wind. However, it remains unclear whether the Venusian hydrogen corona dynamically responds to variations in solar wind conditions.

Observation

To address this question, we analyzed variations in global hydrogen column densities derived from the brightness of resonantly scattered Ly-α (121.6 nm) and Ly-β (102.6 nm) emissions observed by Hisaki[3-5], solar wind velocities and densities measured by ASPERA-4 on Venus Express[6], and solar UV irradiance at Ly-α and Ly-β wavelengths obtained from the Flare Irradiance Spectral Model (FISM) for Planets[7]. The analysis periods spanned March 9 to April 3, 2014 (Period1), and April 25 to May 23, 2014 (Period2). High-speed solar wind events were confirmed during Period1 but not during Period2.

Result

We derived variations in hydrogen column density at altitudes above approximately 310 km and 90 km from the observed Ly-α and Ly-β airglow brightness. Figure 1 shows that after the arrival of high-speed solar wind originating from a corotating interaction region (CIR) in Period1, the hydrogen column density derived from Ly-α increased by approximately 18% within a few days and subsequently remained nearly constant for several weeks. In contrast, the hydrogen column density derived from Ly-β remained relatively stable throughout the same period. Differences between Ly-α and Ly-β brightness suggest an increase in hydrogen atom abundance at higher altitudes during high-speed solar wind events. In Period 2, when no significant increase in both solar wind velocity and density was observed, there was no clear indication of the arrival of a corotating interaction region. During this period, the hydrogen column density remained nearly constant for both Ly-α and Ly-β.

Figure1 (a and b)Times series of column densities of Venusian hydrogen atoms derived from Ly-α and Ly-β observed by Hisaki respectively. The red line indicates the 1-day moving average. (c and d) Solar wind velocity and density respectively observed by Venus Express.

Discussion

A possible explanation for the observed ~18% variation in Ly-α emission is an increase in high altitude hot hydrogen abundance due to charge exchange reactions and momentum transfer between neutral hydrogen and ionospheric ions. By considering charge exchange between cold hydrogen and ionospheric ions as a production process, and charge exchange between hot hydrogen and the solar wind as a loss process, we estimated the reaction timescales and found consistency with the observed variation. Alternative explanations include an increase in low-altitude cold hydrogen abundance or a rise in hydrogen temperature. These findings provide important implications for understanding non-thermal hydrogen escape mechanisms, thus contributing significantly to our knowledge of the atmospheric evolution of Venus.

[1] Chaufray, J. Y., et al., Icarus, 217, 2, 767, 2012

[2] Hodges, R. R., and E. L. Breig, Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 96, 7697, 1991

[3] Yoshikawa, I., et al., Space Science Reviews, 184, 237, 2014

[4] Yoshioka, K., et al., Planetary and Space Science, 85, 250, 2013

[5] Yamazaki, A., et al., Space Science Reviews, 184, 259, 2014

[6] Barabash, S., et al., Planetary and Space Science, 55, 12, 1772, 2007

[7] Chamberlin, P. C., et al., Space Weather, 6., S05001, 2008

How to cite: Nose, C., Masunaga, K., Tsuchiya, F., Sakai, S., Kasaba, Y., Yoshikawa, I., Yamazaki, A., Murakami, G., Kimura, T., Kita, H., Chaufray, J.-Y., and Leblance, F.: Influence of the solar wind on the Venusian hydrogen in upper atmosphere observed by Hisaki, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1791, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1791, 2025.

Abstract

We present a new derivation of the hot oxygen density in the Venusian upper exosphere from Pioneer Venus Orbiter ultraviolet spectrometer, considering the effect of the solar photons backscattered by the oxygen atoms below ~ 300 km (Venus shine), not included in past analysis. The Venus shine increases the volume emissivity of the hot oxygen corona by ~60% compared to the direct illumination and the O I 130.4 nm brightness measured by PVO with a hot oxygen is reproduced with adensity reduced by 1.6 compared to the density derived without the Venus shine.

Introduction

At the surface of Venus, the atmosphere is predominantly composed of CO2 but, above ~150 km, O, generated through the photodissociation of CO2 [1] and dissociative recombination of O2+ becomes dominant [2]. Solar EUV photons not only dissociate neutral molecules in the thermosphere but also ionize them, driving the formation of Venus’ ionosphere. The dominant ion in the Venusian ionosphere is O2+ produced from reactions between CO2+ and O [3]. The major sink of O2+ is dissociative recombination, which produced two energetic atoms. These energetic atoms were first observed in the exosphere of Venus by the PVO ultraviolet spectrometer (UVS) between ~400 – 1600 km [4]. However, these values were derived considering only the direct solar illumination of the oxygen corona above 400 km as the source of O I 1304 emission not the photons resonantly backscattered by the cold oxygen atoms (Venus shine) [5]. In this work, we include the Venus shine.

Model

We use a radiative transfer model, used in the past to study the Martian hot oxygen corona [6]. This model considers spherically symmetric cold and hot oxygen densities and use a Monte Carlo approach to compute the O I 1304 resonant scattering. Test particles, representative of the solar photons in the 130.4 nm triplet [7] are followed inside the Venusian thermosphere and exosphere. The spectral emission volume rate ε(r,λ,i) at the position r and wavelength λ of each line i of the triplet is the sum of five terms:

ε(r,λ,i)=ε0,c(r,λ,i)+εm,c(r,λ,i)+ε0,h(r,λ,i)+εs,h(r,λ,i)+εm,h(r,λ,i)

The two first terms are the single scattering and multiple scattering terms of the cold oxygen. The three last terms are the single scattering (photons scattered for the first time by a hot oxygen atom and not before), “shine term” (photons scattered for the first time by a hot oxygen atom but scattered one or several times by a cold oxygen before) and multiple scattering terms (photons scattered several times by a hot oxygen atom) for the hot oxygen.

Results and discussion

The shine term of the hot population, using the density profiles from [4] and normalized by the g-factor is not negligible compared to the single scattering term on the dayside below 2000 km but decreases faster with altitude (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1 (left) Altitude profile for the single-scattering (blue), multiple-scattering (red), and shine from the cold oxygen (green) volume emission rate (normalized by the g-factor) at SZA=0° of the hot oxygen. The hot oxygen density is indicated by the black line. (right) Variations of the same volume emission rates with the solar zenith angle for an altitude near 600 km.

Above ~400 km, the volume emission rate of the cold population is negligible and the brightness I(z) along the line of sight can be simplified by

I(z) ≈∑∫∫[ε0,h(r,λ,i)+εs,h(r,λ,i)]dsdλ ≈gexc∫[1+Gc(s)]nhot(s)ds,

where Gc is the ratio between the “shine” term and the single scattering term, and nhot(s) the density of hot oxygen.

The simulated brightness using the hot oxygen density derived by [4] with and without the shine term are compared to the observed brightness, showing that when the shine term is considered, the hot oxygen density derived by [4] is not in agreement with the observations. This hot density must be reduced by ~ 1.6 to agree with the observations when the shine term is considered (Fig. 2)

Figure 2. Simulated brightness vertical profile, when the shine term is neglected (solid green line) and included (solid red line) obtained with the hot oxygen density from [3]. The simulated profile including the shine term but with a hot oxygen density divided by 1.6 is also represented (red dashed line). The PVO-UVS data fit from [4] is represented by the black diamonds and the fit from [5] is represented by the black triangles.

This reduced density underscores the need to revisit previous models of hot oxygen corona [8, 9, 10]. Indeed, as shown by [8], the inclusion of non-elastic collisions can lead to a more efficient thermalization. These authors found that the simulated hot oxygen was underestimated compared to the PVO observations [3]. The new inferred density, including the Venus shine, could help to reconcile this simulation with the observation.

Conclusion

We revised the hot oxygen density in the Venusian upper atmosphere derived from Pioneer Venus Orbiter by using an updated radiative transfer model including the Venusian shine emission. This correction increases the excitation frequency of the hot atoms. Then, the oxygen density needed to reproduce the observations is reduced by 1.6 compared to the past derived density. This reduction requires reassessing key assumptions in exospheric models, particularly the roles of inelastic collisions of the hot oxygen with the atmosphere. Indeed, these collisions would increase the thermalization of the hot oxygen and then reduce their density that could match better the new derived density.

Acknowledgements

JYC is supported by the Programme National de Planétologie (PNP, France) of CNRS-INSU co-funded by CNES and Programme National Soleil Terre (PNST, France) of CNRS-INSU co-funded by CNES and CEA

References

[1] Martinez, A., et al. (2023), Icarus, 389, 115272, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115272

[2] Martinez, A., et al. (2024), Icarus, 415, 116035, doi :10.1016/j.icarus/2024.116035

[3] Fox, J., and Sung, K.Y., (2001) JGR, 106, 21,305-21,336, doi:10.1029/2001JA000069

[4] Nagy, A..F., et al., (1981), Geophys. Res. Lett., 8, 629-632

[5] Paxton, L.J., and Anderson, D.E., (1992), Geophysical Monograph, 66

[6] Chaufray, J-Y et al. (2016), JGR, 121, 11,413-11,421, doi:10.1002/2016JA023273

[7] Gladstone, G.R., (1992), J. Geophys. Res., 97, 19,519-19,525

[8] Gröller, H., et al. (2010), J. Geophys. Res., 115, E12017, doi:10.1029/2010JE003697

[9] Tenishev, V. et al. (2022), JGR : Space Phys., 127 ,doi:10.1029/2021JA030168

[10] Hodges Jr., R.R, (2000), J. Geophys. Res., 105, 6971-6981

How to cite: Chaufray, J.-Y., Carberry Mogan, S., and Deighan, J.: Effect of the planet shine on the corona: Application to the Venusian hot oxygen, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-768, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-768, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

The existence of carbon dioxide (CO₂) clouds in the Martian atmosphere necessitates extremely low temperatures for formation and was initially observed during polar night at low altitudes. Later observations revealed similar clouds at higher altitudes near the equator, especially during spring and summer [1]. Further evidence has shown their occurrence at northern mid-latitudes and in the southern hemisphere during late autumn. Unlike water vapour clouds, which form from a minor atmospheric component, CO₂ clouds are composed of a major atmospheric constituent. The polar CO₂ clouds are convective in nature. Data from multiple missions indicate that the temperature profiles in the polar regions often align with the CO₂ saturation curve up to 30 km, implying that CO₂ condensation helps regulate these temperatures. Significant cloud opacity between 0 and 25 km altitude also supports the presence of CO₂ clouds.

Figure 1: Formation of CO2 clouds in the Martian atmosphere [2].

Data from the Pathfinder mission indicate that CO₂ exceeded saturation levels during equatorial descent phases at altitudes near 80 km, implying that CO₂ cloud formation in equatorial regions may occur at significantly higher altitudes compared to polar regions [3]. The genesis of these high-altitude equatorial CO₂ clouds is modulated by conditions in the Martian mesosphere. Notably, mesospheric temperatures can drop well below the CO₂ condensation threshold, particularly near aphelion, when diurnal atmospheric tides promote additional cooling conducive to cloud formation. Furthermore, high-altitude CO₂ cloud formations were detected at solar longitudes between 264° and 330°, located above 90 km in altitude [4]. These clouds exhibit limited horizontal extent, spanning approximately 500 to 700 km.

This study investigates Martian CO2 cloud formations and their duration during the Northern Hemisphere winter and dust season. For this, we use the open-access data from the Mars Climate Sounder (MCS) on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) as well as Mars Express (MEX) and Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MA VEN) radio occultation (RO) to detect clouds in the atmosphere. We also explore the inter-annual variations to see the impact of dust storms on CO2 cloud formation.

Figure 2: Examples of MCS temperature profiles (blue) with the CO2 saturation curve [5].

References:

[1] Määttänen A. et al. (2010), Icarus, 209(2) :452–469.

[2] Mars Climate Modelling Centre. GCM overview: Lecture, November 2021.

[3] Schofield J. T. et al. (1997), Science, 278(5344) :1752–1758.

[4] Jiang F. Y. et al. (2019), GRL, 46(14) :7962–7971.

[5] Mathilde V. (2024), Master Thesis, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium.

How to cite: Krishnan, A. and Karatekin, Ö.: Martian CO2 cloud formation as observed by MCS and radio occultation, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1352, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1352, 2025.

Water vapor has long been a key target in Martian exploration, as its detection confirmed the existence of an active water cycle driven by dynamic exchanges between surface ice reservoirs and the atmosphere. Since its first spectroscopic identification in 1963, ongoing observations—most notably from orbiting spacecraft—have significantly advanced our understanding of the spatial and temporal behavior of water on Mars.

In this study, we present a comprehensive climatology of water vapor column abundances spanning 11 Martian years (MY), derived from observations by the Spectroscopy for the Investigation of the Characteristics of the Atmosphere of Mars (SPICAM) instrument aboard the European Space Agency’s Mars Express mission [1]. Operating in nadir, SPICAM measures the near-infrared sunlight reflected from the Martian surface and atmosphere, providing daytime water vapor data with broad seasonal and latitudinal coverage. However, due to its reliance on solar illumination, SPICAM is unable to probe the polar night, where water vapor is predicted to be extremely scarce and mostly below the instrument’s detection threshold.

Despite the limitations imposed by the orbital configuration of Mars Express—which results in uneven spatial and temporal coverage—SPICAM has successfully monitored the Martian atmosphere across nearly all seasons and latitudes during local daytime conditions. This long-term dataset offers a unique opportunity to study interannual variability in the water cycle, including responses to major atmospheric perturbations.

Our climatology includes two Martian years that experienced Global Dust Events (GDEs), allowing us to conduct a preliminary assessment of how such planet-encircling storms impact water vapor distribution. We also perform cross-comparisons with water vapor datasets from other past and ongoing missions, addressing a long-standing challenge in reconciling inter-mission measurements.

To enhance the completeness of the climatology, we apply the kriging method—a well-established geostatistical interpolation method based on Gaussian process regression—to estimate water vapor values in regions and seasons with sparse coverage. This gap-filling enables a more continuous picture of the Martian water cycle and facilitates the analysis of year-to-year variability.

Finally, by averaging over the full 11-MY dataset, we construct a reference annual cycle of water vapor on Mars, which serves as a baseline for future comparisons, model validation, and the identification of anomalous behavior.

To further improve the accuracy and vertical sensitivity of water vapor retrievals, we also incorporate results from a synergistic retrieval approach developed by [2] and [3] This method combines simultaneous nadir-pointing observations from SPICAM (in the near-infrared) and the Planetary Fourier Spectrometer (PFS, in the thermal infrared), both aboard Mars Express. Individually, each instrument is sensitive to different portions of the atmospheric column—SPICAM to the lower atmosphere under illuminated conditions, and PFS to higher altitudes through thermal emission. When used together in a joint retrieval framework, they offer a more complete and vertically constrained view of water vapor distribution than either instrument alone.

The synergy method thus yields more accurate water vapor column abundances and enables the first nadir-based estimates of vertical partitioning of water vapor—an aspect traditionally inaccessible to single-instrument nadir retrievals. The resulting composite dataset, which spans almost the entire SPICAM survey, has proven to be highly robust and serves as an important reference for climatological studies. Notably, the synergy also reveals significant discrepancies with predictions from the Mars Climate Database, especially in the northern hemisphere during summer, highlighting potential limitations in current models of water vapor transport and vertical confinement.

Finally, in addition to nadir observations, SPICAM also conducted measurements in solar occultation mode [4], which allowed the retrieval of vertical profiles of water vapor at high vertical resolution (~1–2 km), primarily during the twilight terminator. These observations complement the nadir dataset by providing a window into the vertical structure of water vapor in the lower and middle atmosphere (typically from 10 to 70 km), including its diurnal variations and seasonal evolution. Solar occultation data are especially valuable in characterizing the hygropause altitude, tracking the seasonal ascent and descent of water vapor, and capturing sharp vertical gradients during northern summer, when water transport to high altitudes is most active.

This work not only contributes to a more detailed understanding of Mars’ water cycle dynamics but also provides critical observational constraints for atmospheric models and climate evolution studies.

[1] Montmessin, F., Korablev, O., Lefèvre, F., Bertaux, J.-L., Fedorova, A., Trokhimovskiy, A., et al. (2017). SPICAM on Mars Express: A 10 year in-depth survey of the Martian atmosphere. Icarus, 297, 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2017.06.022

[2] Montmessin, F., & Ferron, S. (2019). A spectral synergy method to retrieve martian water vapor column-abundance and vertical distribution applied to Mars Express SPICAM and PFS nadir measurements. Icarus, 317, 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.07.022

[3] Knutsen, E. W., Montmessin, F., Verdier, L., Lacombe, G., Lefèvre, F., Ferron, S., et al. (2022). Water Vapor on Mars: A Refined Climatology and Constraints on the Near‐Surface Concentration Enabled by Synergistic Retrievals. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 127(5). https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007252

[4] Fedorova, A., Montmessin, F., Korablev, O., Lefèvre, F., Trokhimovskiy, A., & Bertaux, J. (2021). Multi‐Annual Monitoring of the Water Vapor Vertical Distribution on Mars by SPICAM on Mars Express. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 126(1). https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JE006616

How to cite: Montmessin, F., Fedorova, A., Verdier, L., Korablev, O., Lefèvre, F., Trokhimovskiy, A., Knutsen, E. W., Lacombe, G., Baggio, L., Giuranna, M., and Wolkenberg, P.: Mars water cycle: an 11 Mars year climatology of water vapor by SPICAM on Mars Express, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-932, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-932, 2025.

Water is an important component of the atmosphere. Most of the water vapor of Mars exists in its lower atmosphere, including the planetary boundary layer, where the water vapor exchanges between the surface and the atmosphere. The regolith, which is a loose, unconsolidated material consisting of fine dust, sand, and fragmented rock at the planetary surface, has a water-adsorbing property (Fanale & Cannon, 1971; Zent & Quinn, 1995). 1-D model simulations suggest that the water vapor exchange between the regolith and the atmosphere through adsorption affects the diurnal variations of water vapor near the surface and obtain good agreement with lander observations (Zent et al., 1993; Savijärvi et al., 2016, 2019; Savijärvi & Harri, 2021). However, the observation of the daytime water vapor column map suggests that water is not well mixed in the atmosphere, with a significant part of the water vapor column apparently not influenced by the topography (Smith, 2002, Fouchet et al., 2007) as it should be if it were well mixed. This could be explained by an enrichment near the surface, possibly related to water exchanges with the regolith, or by an enrichment well above the surface, for instance, below the cloud level where ice sublimes (Fouchet et al., 2007). This study investigates the effects of the water vapor exchange between the regolith and the atmosphere to explain the observed spatial distribution of the atmospheric water vapor column.

This study uses a Mars Global Climate Model (MGCM) fully coupled with a regolith model. Our MGCM traces the Martian seasonal water cycle, including seasonal water ice caps and frost formation, turbulent flux in the atmospheric boundary layer (Kuroda et al, 2005, 2013), and simple cloud formation based on the large-scale condensation (Montmessin et al., 2004). The regolith model calculates water vapor diffusion, adsorption, and condensation in the regolith, using an adsorption coefficient as a free parameter (Kobayashi et al., 2025). The adsorption isotherm of Jakosky et al. (1997) is used to obtain the adsorbed water amount in the regolith, and the isotherm assumes palagonite on Mars. We examine several adsorption coefficients including zero (only considering pore ice) and the inhomogeneous adsorption coefficient using the regolith property model (Kobayashi et al., 2025). The annual mean water flux in high latitudes, where stable ice tables thermodynamically exist, is less than 10-10 kg m-2 s-1 because pore ice fills pores and prevents water transport. We use the atmospheric water vapor column abundance normalized to a fixed pressure of 610 Pa to remove the effect of topography (Smith, 2002).

The subsurface layers are initialized with the subsurface water amount obtained from a spin-up run without the regolith-atmosphere interaction for approximately tens of thousands of Martian years. With the globally homogeneous adsorption coefficient, the subsurface adsorbed water amount increases with latitudes up to ±60° (corresponding to the annual mean surface temperature of 195 K) and rapidly decreases in higher latitudes. With the inhomogeneous adsorption coefficient, the subsurface adsorbed water amount is strongly controlled by the adsorption coefficient, leading to higher adsorbed water in areas of higher adsorption coefficient. We used those results as initial conditions of the subsurface water amount for the following simulations of the regolith-atmosphere interaction.

Our results show that a larger source of adsorbed water in the regolith supplies more water vapor into the atmosphere, with a small adsorption coefficient dependence. The daytime water vapor normalized to 610 Pa anti-correlates with the surface pressure and with thermal inertia in some seasons. The anti-correlations with the surface pressure and with thermal inertia are very slightly strengthened by the regolith-atmosphere interaction. There results indicate that the regolith adsorption contributes to the not-well mixed condition in the Martian lower atmosphere, and the effect is smaller than expected. The exchanged water flux at the surface in our simulation is approximately 10-10-10-9 kg m-2 s-1, corresponding to 10-2-10-1 pr-µm per 1 sol and increasing polewards, for any adsorption coefficient. Thus, we estimate that the regolith-atmosphere interaction integrated over hundreds of sols affects the change of up to several precipitable microns, and the amount becomes smaller due to transport. The magnitude is small or comparable to the sensitivity of the orbital observations nowadays (Fouchet et al., 2007). We conclude that the anti-correlation of water vapor with the surface pressure and with thermal inertia would not be fully explained by the regolith-atmosphere interaction alone, and it would be necessary to focus on transport near the ground surface.

How to cite: Kobayashi, M., Kuroda, T., Forget, F., Kamada, A., Kurokawa, H., Aoki, S., Kazama, A., Nakagawa, H., and Terada, N.: Effects of regolith-adsorption on the spatial distribution of the atmospheric water vapor simulated with a Mars GCM, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-834, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-834, 2025.

Homogeneous nucleation has not been considered a possibility in cloud formation processes in the atmosphere of Mars (e.g. Clancy et al., 2017), since Määttänen et al. (2005) made a careful analysis that indicated that extreme supersaturations in the order of 10⁵ were required. Such extreme supersaturations were considered unlikely, especially because the abundant dust in the atmosphere of Mars was expected to deplete water in excess of saturation very quickly by heterogeneous nucleation.

The Arsia Mons Elongated Cloud (AMEC) is an eye-catching and mysterious cloud occurring recurrently every morning during the perihelion season over the Arsia Mons volcano on Mars (Hernández-Bernal et al., 2021). It shows a peculiar elongated shape that in only 3 hours expands up to 1800 km from its origin point. Hernández-Bernal et al. (2022) investigated this cloud based on the LMD Mars Mesoscale model (Spiga and Forget, 2009). The tail of the cloud was not reproduced in the model, but a cold pocket with temperatures down to 30K below the environment and supersaturation up to 105 appeared next to Arsia Mons, in a position, altitude, and local time and season coincident with the origin point of the AMEC in observations.

In this work we show that these are conditions conducive to homogeneous nucleation, and when we introduce this process as a new cloud formation process in the LMD Mars Mesoscale model, we obtain a good representation of the AMEC, and its long tail.

This provides an excellent explanation for this mysterious cloud and shows that homogeneous nucleation is possible and can have significant effects in the atmosphere of Mars, contrary to the widespread assumptions during the last twenty years of Mars exploration. The finding of supersaturations up to 108 in the surveys performed by Fedorova et al. (2020; 2023) observationally supports that these extreme supersaturations can indeed happen in the atmosphere of Mars and homogeneous nucleation could be happening in other clouds. As a first example, we find that the Perihelion Cloud Trails (Clancy et al., 2009; 2021) could be the result of homogeneous nucleation, as our mesoscale model also predicts cold pockets spatially coincident with locations where Clancy et al. observed cloud trails. We intend to explore these and other clouds on Mars possibly involving homogeneous nucleation.

References:

- Clancy, R. T., Wolff, M. J., Cantor, B. A., Malin, M. C., & Michaels, T. I. (2009). Valles Marineris cloud trails. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 114(E11). https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JE003323

- Clancy, R., Montmessin, F., Benson, J., Daerden, F., Colaprete, A., & Wolff, M. (2017). Mars Clouds. In R. Haberle, R. Clancy, F. Forget, M. Smith, & R. Zurek (Eds.), The Atmosphere and Climate of Mars (Cambridge planetary science (pp. 76–105). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781139060172.005

- Clancy, R. T., Wolff, M. J., Heavens, N. G., James, P. B., Lee, S. W., Sandor, B. J., ... & Spiga, A. (2021). Mars perihelion cloud trails as revealed by MARCI: Mesoscale topographically focused updrafts and gravity wave forcing of high altitude clouds. Icarus, 362, 114411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114411

- Määttänen, A., Vehkamäki, H., Lauri, A., Merikallio, S., Kauhanen, J., Savijärvi, H., & Kulmala, M. (2005). Nucleation studies in the Martian atmosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 110(E2). https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JE002308

- Fedorova, A. A., Montmessin, F., Korablev, O., Luginin, M., Trokhimovskiy, A., Belyaev, D. A., ... & Wilson, C. F. (2020). Stormy water on Mars: The distribution and saturation of atmospheric water during the dusty season. Science, 367(6475), 297-300. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay9522

- Fedorova, A., Montmessin, F., Trokhimovskiy, A., Luginin, M., Korablev, O., Alday, J., ... & Shakun, A. (2023). A two‐Martian years survey of the water vapor saturation state on Mars based on ACS NIR/TGO occultations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 128(1), e2022JE007348. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007348

- Hernández‐Bernal, J., Sánchez‐Lavega, A., del Río‐Gaztelurrutia, T., Ravanis, E., Cardesín‐Moinelo, A., Connour, K., ... & Hauber, E. (2021). An extremely elongated cloud over Arsia Mons volcano on Mars: I. Life cycle. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 126(3), e2020JE006517. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JE006517

- Hernández‐Bernal, J., Spiga, A., Sánchez‐Lavega, A., del Río‐Gaztelurrutia, T., Forget, F., & Millour, E. (2022). An extremely elongated cloud over Arsia Mons volcano on Mars: 2. Mesoscale modeling. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 127(10), e2022JE007352. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007352

- Spiga, A., & Forget, F. (2009). A new model to simulate the Martian mesoscale and microscale atmospheric circulation: Validation and first results. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 114(E2). https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JE003242

How to cite: Hernandez-Bernal, J., Määttänen, A., Spiga, A., and Forget, F.: Homogeneous nucleation on Mars. An unexpected process that deciphers mysterious elongated clouds, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1600, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1600, 2025.

Introduction

Water ice clouds play an important role in the Martian water cycle and climate as they are a major actor in the inter-hemispheric water exchange, and impact the atmospheric structure and temperature by absorbing and scattering the incoming solar radiation [1,2 and references contained within]. Thus, monitoring the spatial and temporal evolution of the Martian water ice clouds, along with their physical properties (crystal effective radius, opacity, and altitude) is of importance to improve our understanding and modeling of the current Martian climate.

Plus, we showed in [3] that the vertical structure of the clouds has a non-negligible impact on cloud optical depth retrievals performed from nadir measurements; and in [4] that the current climate models such as the Planetary Climate Model (PCM) [5] still tends to slightly underestimate the altitude of the water ice clouds. Thus, there is a need for a climatology of the vertical structure of the clouds to improve both the atmospheric models, and the nadir clouds surveys that are the main way to perform spatial and temporal surveys of water ice clouds on Mars [e.g., 6,7,8].

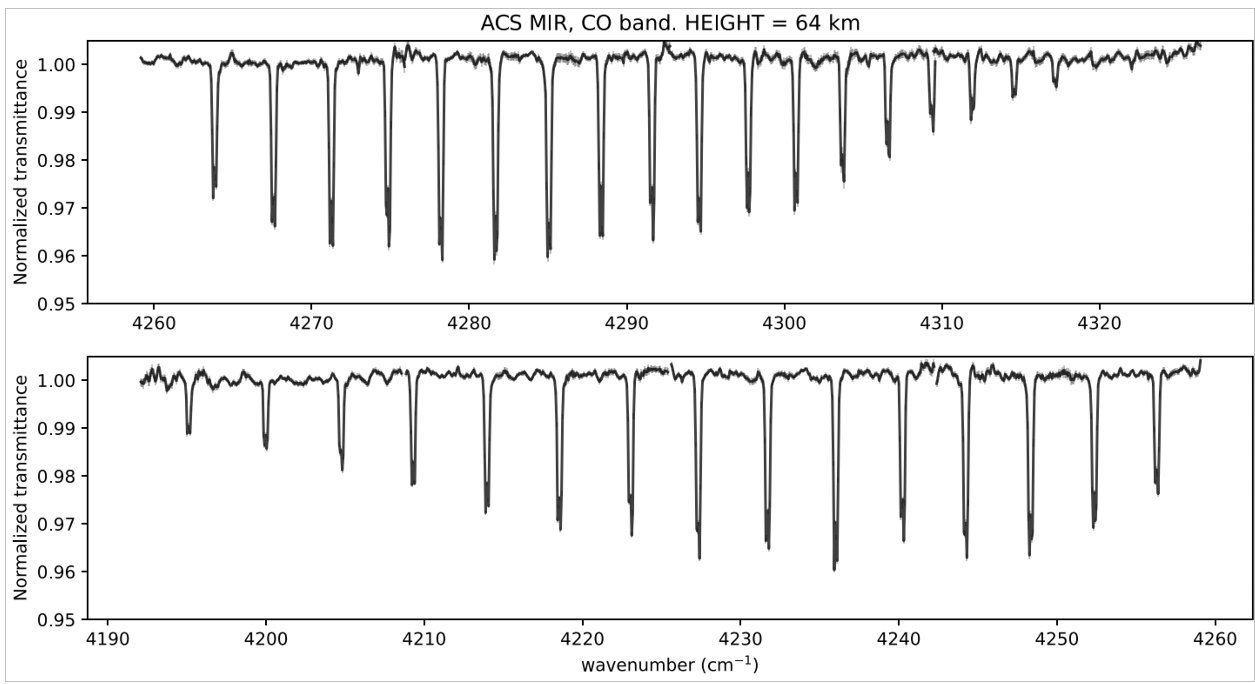

Data & Methods

The Atmospheric Chemistry Suite (ACS) Mid-InfraRed (MIR) channel is a high-resolution spectrometer dedicated to Solar Occultation geometry onboard the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) ESA-Roscosmos spacecraft [9,10]. This observing geometry provides detailed vertical profiles of the atmospheric transmission. In this study, we use ACS-MIR observations acquired in the so-called position 12 of the secondary grating, which covers the 3.1–3.4 μm spectral range to retrieve the properties of the Martian water ice clouds from their 3 μm absorption band. Following the method described in [11,4], we extract the spectral continuum of the atmospheric transmission at each altitude observed by ACS-MIR (typical vertical resolution of ~2.5 km), then we perform an onion-peeling vertical inversion to retrieve the spectral extinction of each atmospheric layer, and we compare these spectra with models for water ice and dust particles of various sizes to identify the layers where water ice crystals are present, and get constraints on their effective radii.

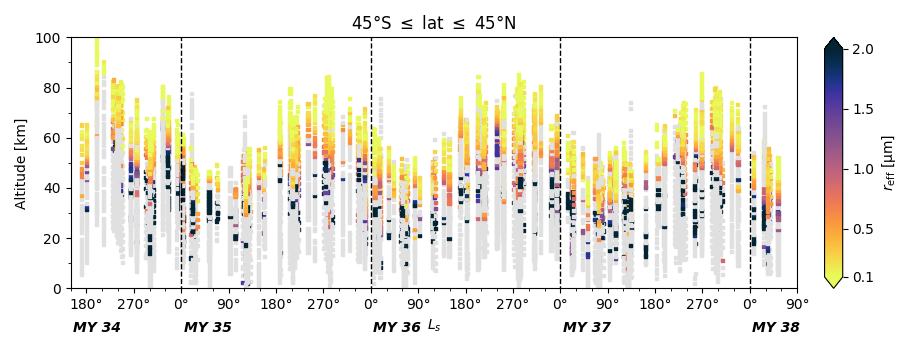

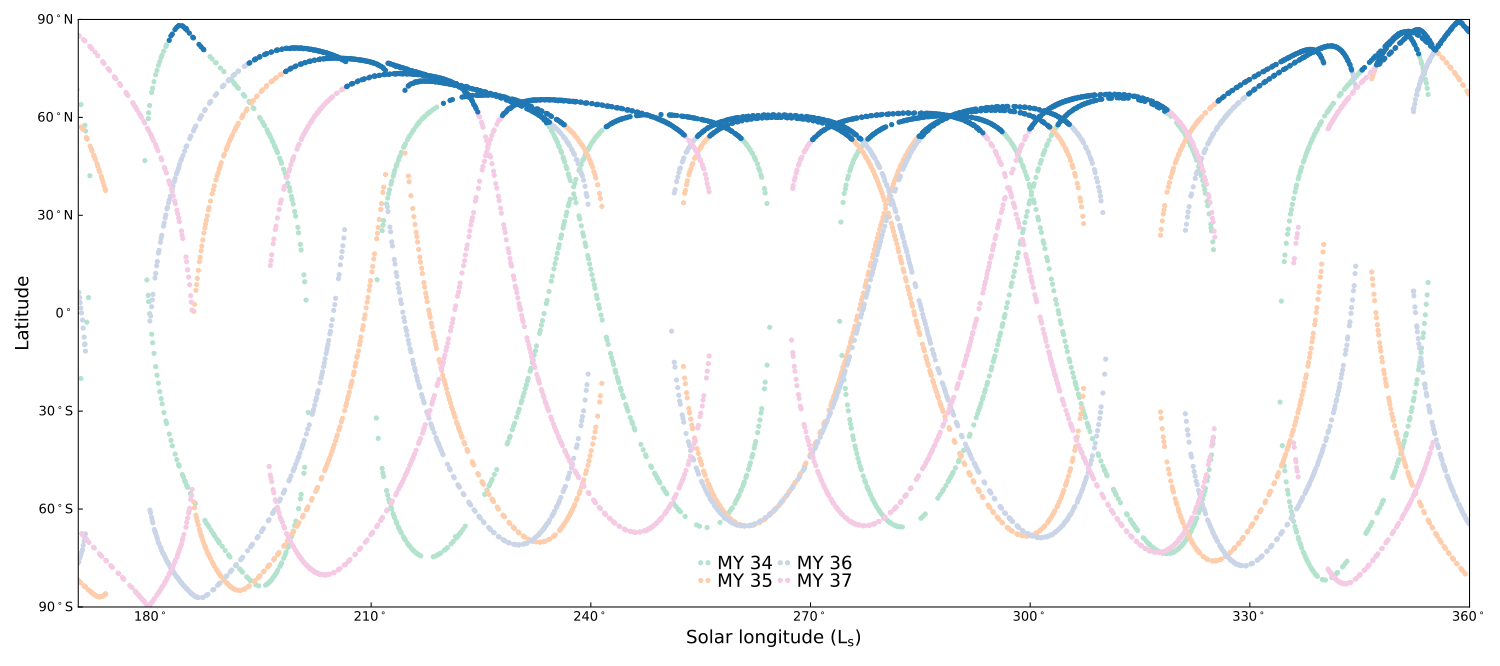

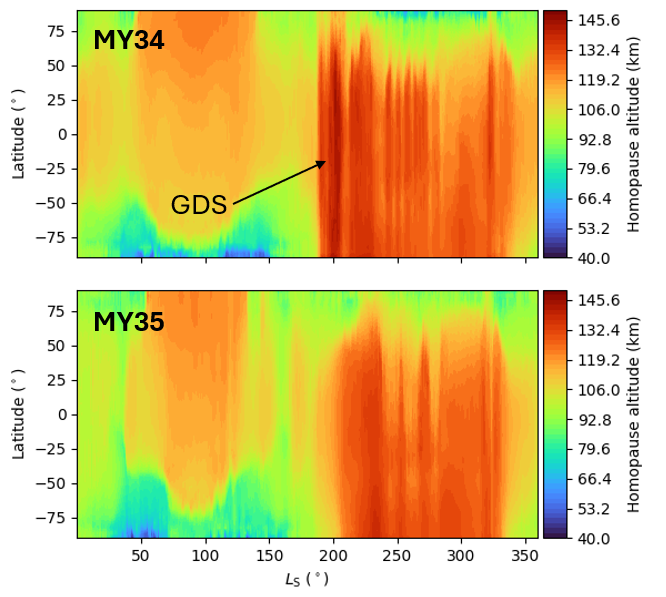

At the time of the publication of [4] in 2022, we had a dataset containing 514 observations acquired between Ls=163° (MY 34) and Ls=181° (MY 36). Now, with two more years of data, we processed an extended dataset of ~1500 observations running until Ls=72° (MY 38). In addition, we use new data for ACS-MIR observations processed at LATMOS that provide better corrections from instrumental effects, which will help to strengthen again our results.

Results

The ACS-MIR clouds dataset now encompasses four Martian Years (MY 34 to 38), including the Global Dust Storm (GDS) event in the end of MY 34, and three "regular" years (i.e., without GDS) with several local dust storms. This allows us to monitor the behavior of the clouds as a function of season and latitude for several MY, and conduct inter-annual comparisons between the regular MY and the GDS of MY 34.

Figure 1 shows the vertical profiles of the water ice clouds obtained in the equatorial regions from Ls=163° (MY 34) to Ls=72° (MY 38). We can see that the altitude of the clouds typically varies by about 30–40 km over the year: they do not extend over 45 to 50 km around aphelion (Ls ~ 90°) but they can easily reach 80 km around perihelion (Ls ~ 270°). This pattern and altitudes are observed for MY 35 to 38, which highlights the unusual altitudes of the clouds during the GDS, where water ice crystals have been detected up to 100 km at Ls ~ 180°.

Figure 1 – Vertical profiles of water ice clouds in the Martian atmosphere as observed by ACS-MIR over mid-MY 34 (Ls=163°) to the beginnirg of MY 38 (Ls=72°) in the equatorial regions (latitudes between 45°S and 45°N), with their crystal size determined using the method described in [4]. Observations without water ice detections are in gray.

Conclusion & Perspectives

To conclude, we present here the results of the monitoring of the vertical distribution and properties of the Martian water ice clouds over more than three Martian Years by ACS-MIR, since the beginning of the science phase of TGO in April 2018. We now have access to a unique and rich dataset for the Martian clouds and climate science, which allows us to discuss the multi-annual evolution of the Martian water ice clouds, and to derive a new climatology of the vertical structure of the clouds in the atmosphere that will be of significant interest for helping to improve both the climate models and the retrievals performed using radiative transfer algorithm that currently relies on assumptions on the vertical distribution of the ice and aerosols in the atmosphere.

Acknowledgments

ExoMars is a space mission of ESA and Roscosmos. The ACS experiment is led by IKI Space Research Institute in Moscow. The project acknowledges funding by Roscosmos and CNES. Science operations of ACS are funded by Roscosmos and ESA. Science support in IKI is funded by Federal agency of science organization (FANO). Raw ACS data are available on the ESA PSA at https://archives.esac.esa.int/psa/#!Table%20View/ACS=instrument. ACS-MIR level 2B data are available on the LATMOS servers, as described at https://acs.projet.latmos.ipsl.fr/en/data. A. S. also acknowledges funding by CNES.

References

[1] Clancy et al. (2017) The Atmosphere and Climate of Mars, 76–105. [2] Montmessin et al. (2017) The Atmosphere and Climate of Mars, 338–373. [3] Stcherbinine et al. (2025) Icarus, 425, 116335. [4] Stcherbinine et al. (2022) JGR: Planets, 127, e2022JE007502. [5] Forget et al. (2022) 7th MAMO workshop. [6] Wolff et al. (2022) GRL, 49, e2022GL100477. [7] Smith et al. (2022) GRL, 49, e2022GL099636. [8] Atwood et al. (2024) Icarus, 418, 116148. [9] Korablev et al. (2018) SSR, 214(1), 7. [10] Trokhimovskiy et al. (2015) SPIE, 960808. [11] Stcherbinine et al. (2020) JGR: Planets, 125, e2019JE006300.

How to cite: Stcherbinine, A., Montmessin, F., Baggio, L., Vincendon, M., Wolff, M., Korablev, O., Fedorova, A., Trokhimovskiy, A., and Lacombe, G.: A three Martian years climatology of the vertical properties of Martian water ice clouds TGO/ACS-MIR, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1495, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1495, 2025.

Introduction: Isotope ratios in water vapour provide key insights about the history of water on Mars and can help us unravel the fate of the large amounts of liquid water that once existed on the surface of early Mars [1]. A five-fold enrichment of the deuterium-to-hydrogen (D/H) ratio in Martian water vapour with respect to Earth suggests that a substantial amount of the water inventory escaped to space, but more quantitative estimates rely on a rigorous understanding of the relative escape between the light and heavy isotopes (e.g., [2]).

Atmospheric processes such as condensation or photolysis shape the vertical distribution of the water vapour isotopes [3,4] and in turn impact the relative supply of isotopes to the upper atmosphere, where they can escape through thermal and non-thermal processes [5]. Therefore, an in-depth understanding of the vertical distribution of the water vapour abundance and its isotopic fractionation is crucial for reconstructing the escape history of water on Mars.

In this study, we measure and model the vertical distribution of D/H and 18O/16O on Martian water vapour using infrared solar occultation observations from the Atmospheric Chemistry Suite (ACS) aboard the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), together with simulations of the D/H and 18O/16O cycles on Mars from the Mars Planetary Climate Model (PCM).

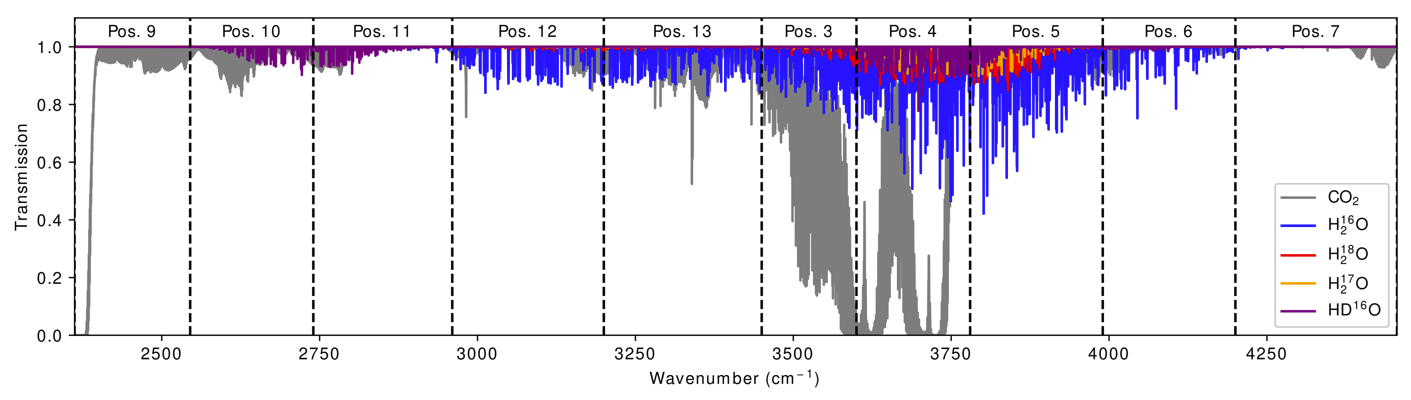

TGO/ACS solar occultation observations: The mid-infrared (MIR) channel of ACS monitors the Martian atmosphere at high spectral resolution (λ/Δλ ≈ 30,000) within the spectral range 2.3-4.2 μm (~2400-4300 cm-1) in solar occultation mode [6]. To achieve high spectral resolution within the whole range, ACS MIR incorporates a secondary movable grating that allows the simultaneous selection of 7-25 diffraction orders.

In this work, we analyse observations made with secondary grating positions #5 and #11, which allow the selection of diffraction orders covering a spectral range of 3780-3990 cm-1 and 2650-2950 cm-1, respectively (see Figure 1). These spectral ranges include the most suitable absorption features to measure the vertical distribution of D/H and 18O/16O from the ACS spectra.

We will present the retrieved vertical profiles of D/H and 18O/16O using this experimental setup and following a retrieval methodology previously validated for the derivation of other isotopic ratios with TGO/ACS [7,8]. In particular, we will focus our analysis on the observations made close to aphelion (LS ~ 70˚) and perihelion (LS ~ 250˚), when the water vapour vertical distribution is particularly different, and discuss the vertical variability of the D/H and 18O/16O isotopic ratios during these two distinct seasons.

Figure 1: Synthetic transmission spectrum of the Martian atmosphere within the spectral range of ACS MIR. The figures shows the instantaneous spectral range covered by ACS MIR when using different secondary grating positions (black dashed lines), as well as the contribution by CO2 and different H2O isotopes to the spectrum (coloured lines) [7].

Simulations with the Mars PCM: Several studies have been conducted to model the variations of the D/H ratio in the atmosphere of Mars (e.g., [3,4,9]), but the variability of the 18O/16O isotopic ratio remains largely unexplored.

In this work, we include the condensation-induced fractionation effect of 18O/16O to the most recent version of the HDO scheme on the Mars Planetary Climate Model [4,10], aiming to simulate the simultaneous fractionation of both water isotopic ratios. This scheme includes the implementation of equilibrium fractionation due to the different saturation vapour pressures of the water isotopes [11,12], as well as the implementation of kinetic effects due to their different diffusivities [13].

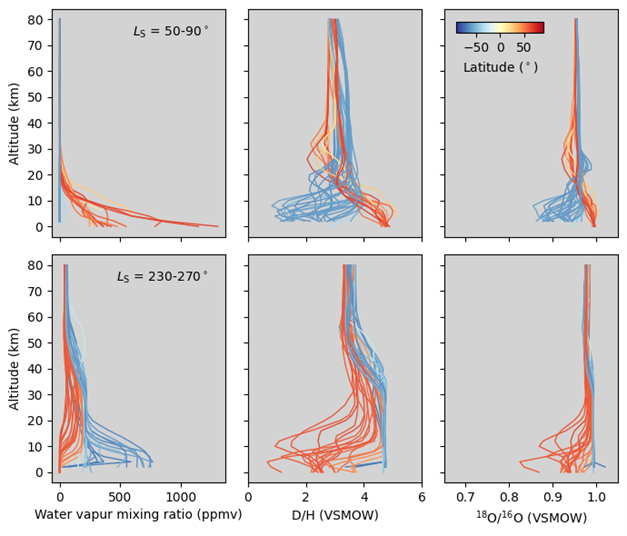

Figure 2 shows the vertical distribution of the D/H and 18O/16O isotopic ratios modelled with the Mars PCM at the locations and times of ACS MIR measurements made during the aphelion and perihelion seasons of Martian Year 35. The altitudinal profiles of these isotopic ratios are driven by the condensation of water, either on the ground in the winter hemispheres, or through the formation of water ice clouds, which form at much higher altitudes during the warmer perihelion season than close to aphelion. While the distribution of both isotopic ratios from the model is very similar, the amplitude of the variations in the 18O/16O isotopic ratio are much smaller than those in D/H.

We will compare the simulations of the D/H and 18O/16O ratios from the Mars PCM with the measured profiles from TGO/ACS, aiming to investigate the relative supply of water isotopes to the Martian upper atmosphere.

Figure 2: Vertical distribution of the water vapour volume mixing ratio, D/H and 18O/16O modelled with the Mars PCM at the locations and times of the ACS MIR during the aphelion (top) and perihelion (bottom) seasons in Martian Year 35. The lines in the different panels are coloured based on the latitude of the locations.

References:

[1] Scheller et al., Science, 2021, eabc7717. [2] Villanueva et al., Science, 2015, 348, 218. [3] Montmessin et al., J. Geophys. Res., 2005, 110, E03006. [4] Vals et al., JGR Planets, 2022, 127. [5] Cangi et al., JGR Planets, 2023, 128, e2022JE007713. [6] Korablev et al., Space Sci. Rev., 2018, 214, 7. [7] Alday et al., Nat. Astron., 2021, 5, 943. [8] Alday et al., Nat. Astron., 2023, 7, 867. [9] Daerden et al., JGR Planets, 2022, 127. [10] Rossi et al., JGR Planets, 2022, 127. [11] Lamb et al., PNAS, 2017, 114, 5612. [12] Majoube, Nature, 1970, 226, 1242. [13] Hellmann & Harvey, JGR Planets, 2021, 126.

How to cite: Alday, J., Patel, M. R., Montmessin, F., Fedorova, A. A., Holmes, J., Petzold, G., Baggio, L., Trokhimovskiy, A., Olsen, K. S., Belyaev, D., Mason, J. P., and Korablev, O.: The vertical distribution of water vapour isotopes on Mars from the Atmospheric Chemistry Suite aboard the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-626, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-626, 2025.

Context : The deuterium/hydrogen isotopic ratio, D/H, is one of the keys to understand the origin of water on terrestrial bodies within the Solar System and its evolution over time in their atmospheres.

In the atmosphere of Mars, this D/H ratio is on average 5 to 6 times higher than the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW), the Earth’s oceans reference. Although water vapor is present only in very low quantities on Mars (100 ppmv on average), it is rich in deuterium, which points to a wetter past for the Red Planet, a fact corroborated by various geological indicators (valleys, ancient lakes, shorelines). This enrichment is understood as a cumulative effect of differential escape between H and D atoms, the latter being more prone to gravity than its lighter isotopologue. This differential escape is deeply rooted into the seasonal behavior of HDO and H₂O, sole precursors of D and H on Mars, which release H and D at high altitude, when climatic conditions allow photochemistry. [1, 2]

Model : The Mars PCM (Planetary Climate Model) simulates the physical, chemical and dynamical processes in the Martian atmosphere, including water ice cloud-related phenomena [3], such as condensation, that fully control the relative behavior of HDO [4, 5]. This model, coupled with observations and data from ACS (Atmospheric Chemistry Suite), has shed light on the HDO cycle recently. However, differences still exist between the model and the observations. This is particularly the case for the vertical distribution of water vapor in the upper atmosphere [5, 6]. Some improvements to the Mars PCM, namely new dust injection scheme and non-orographic gravity waves [7] have been implemented.

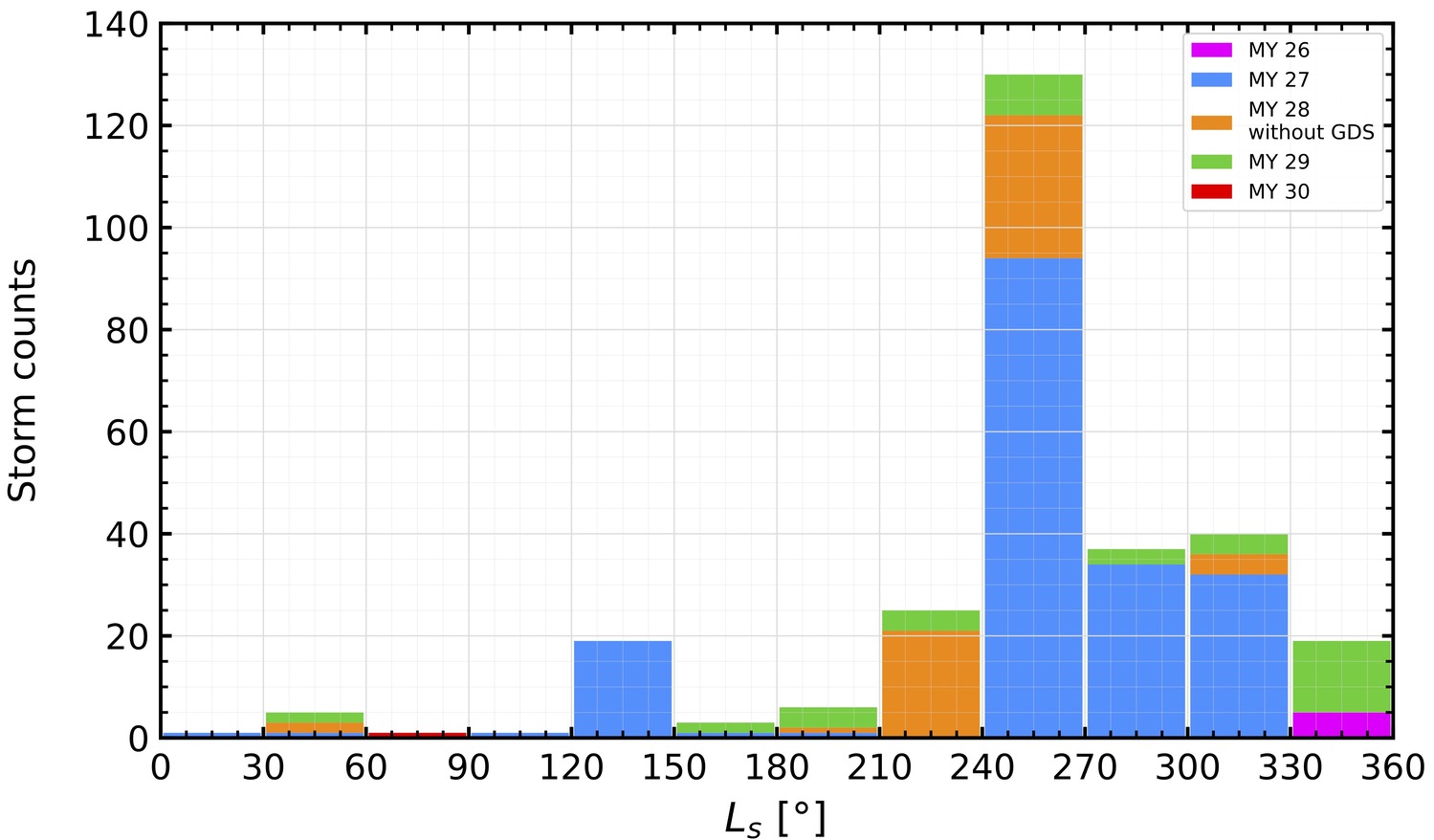

Results : This study presents a 12-Martian-year simulation, covering Martian Years 26 to 37, with a focus on interannual variations in the HDO and H₂O cycles. The results from the model are compared with multiple observations from instruments such as ACS and SPICAM, capturing a wide range of dust events and revealing key processes to which the HDO and H₂O cycles are particularly sensitive and predicted by the Mars PCM. A third moment is being implemented in the dust particles size distribution to improve its vertical distribution with respect to observations. The first outcomes of this modification will also be addressed.

This study is part of a broader effort to better understand the origin and the long-term evolution of the water on Mars. By investigating the processes behind the Mars’ deuterium enrichment, it contributes to unraveling the history of atmospheric escape and climate change on the Red Planet.

References

[1] Villanueva, G. et al. (2015), Strong water isotopic anomalies in the martian atmosphere: probing current and ancient reservoirs, Science

[2] Owen, T. et al. (1988), Deuterium on Mars: The Abundance of HDO and the Value of D/H, Science

[3] Navarro, T. et al. (2014), Global climate modeling of the Martian water cycle with improved microphysics and radiatively active water ice clouds, JGR Planets

[4] Bertaux, J-L. & Montmessin, F. (2001), Isotopic fractionation through water vapor condensation: The Deuteropause, a cold trap for deuterium in the atmosphere of Mars, JGR Planets

[5] Vals, M. et al. (2022), Improved Modeling of Mars' HDO Cycle Using a Mars' Global Climate Model, JGR Planets

[6] Rossi, L. et al. (2022), The HDO cycle on Mars : Comparison of ACS observations with GCM simulations, JGR Planets

[7] Gilli, G. et al. (2020), Impact of Gravity Waves on the Middle Atmosphere of Mars: A Non-Orographic Gravity Wave Parameterization Based on Global Climate Modeling an

How to cite: Petzold, G., Montmessin, F., Alday, J., Verdier, L., Millour, E., Robinson, T., and Robinthal, L.: A twelve-year survey of the HDO and H2O cycles using the Mars Planetary Climate Model from MY26 to MY37, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-957, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-957, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Mars is known to host a variety of auroral processes (Bertaux et al. 2005, Schneider et al. 2015, Lillis et al. 2022) despite the planet’s tenuous atmosphere and lack of a global magnetic field. The first detection of visible-wavelength aurora at 557.7 nm was made in 2024 by the SuperCam and Mastcam-Z instruments on the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover (Knutsen et al. 2025 (in press)), which represented the first observation of aurora from any planetary surface other than Earth, the first detection of visible-wavelength aurora at Mars, and demonstrates that auroral forecasting at Mars is possible. During events with higher particle precipitation, or under less dusty atmospheric conditions, green aurorae will be visible to future astronauts.

Here we present the results of all detection attempts made to date using the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover. We describe the selected solar storms as they were forecasted, and compare with orbital particle and plasma measurements from MAVEN and Mars Express leading up to and during each event, along with the resulting surface aurora detection attempts.

A total of eight detection attempts have been made between May 2023 and August 2024. Two of the targeted solar storms led to successful identification of green aurora at Mars with the SuperCam and Mastcam-Z instruments on the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover.

References

Bertaux, J.-L., et al. "Discovery of an aurora on Mars." Nature 435.7043 (2005): 790-794.

Schneider, N. M., et al. "Discovery of diffuse aurora on Mars." Science 350.6261 (2015): aad0313.

Lillis, R. J., et al. "First synoptic images of FUV discrete aurora and discovery of sinuous aurora at Mars by EMM EMUS." Geophysical Research Letters 49.16 (2022): e2022GL099820.

Knutsen, E. W., et al. (in press), “First detection of visible-wavelength aurora on Mars”, Science Advances (2025).

How to cite: Knutsen, E. W., McConnochie, T. H., Lemmon, M., Viet, S., Cousin, A., Wiens, R. C., and Bell, J. F.: Green-line aurora detection attempts from the surface of Mars , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1314, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1314, 2025.

Argon (Ar) is a chemically inert noble gas used as a tracer to investigate transport processes and energy deposition in the Martian upper atmosphere. Its high atomic mass makes it sensitive to both thermal and non-thermal mechanisms, while its chemical stability ensures that its distribution reflects physical processes occurring in the thermosphere. NGIMS, the Neutral Gas and Ion Mass Spectrometer aboard NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft, has been measuring neutral species including Ar since late 2014, enabling systematic monitoring of the Martian atmosphere from ~150 to over 1000 km in altitude. First studies of Ar densities reflect that below 350 km the population is dominated by thermal processes, whereas above this altitude, detected Ar is primarily attributed to suprathermal components (Mahaffy et al., 2014; Leblanc et al., 2019).

Over its seven years of operation, MAVEN has collected more than 25,000 orbits with NGIMS in neutral mode, including over 1,100 orbits dedicated to high-cadence observations of argon. These targeted campaigns increase vertical resolution and sampling near periapsis and provide enhanced sensitivity up to 1200km. The compiled dataset spans a broad range of local times, solar zenith angles (SZA), seasons (solar longitudes), and latitudes, offering extensive spatial and temporal coverage.

This study investigates the dependence of Ar density on SZA using both standard and high-cadence NGIMS measurements. The resulting profiles indicate systematic variations with SZA, particularly in the 300–1000 km altitude range. Ar densities tend to decrease with increasing SZA, with the strongesat gradients observed above the nominal exobase.

A subset of high-cadence profiles is also examined in greater detail to contextualize vertical structure in terms of MAVEN's orbital geometry, local time, latitude, and season. Particular attention is given to trajectories passes occurring near the morning and evening terminators. These profiles are analyzed individually to assess variability in Ar density structure and its possible relationship to viewing geometry and seasonal conditions. In several cases, localized enhancements in Ar density are detected at altitudes above 700 km. The origin of these features remains under investigation but may be consistent with the influence of waves or perturbations propagating upward from lower atmospheric layers. The apparent asymmetry between dusk and dawn sectors, as previously noted in global maps, is also investigated through this targeted approach.

How to cite: Steichen, V., Leblanc, F. L., and Benna, M.: Vertical Structure and Variability of Argon in Mars’ Exosphere from High-Resolution NGIMS Data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-800, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-800, 2025.

Nightglow emissions in the Mars atmosphere provide critical insights into its composition and dynamics, allowing remote evaluation of atmospheric constituents and photochemical processes. The UVIS spectrometer aboard ESA’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) recently detected a new emission in Mars' atmosphere—the Herzberg II bands of molecular O₂—particularly intense around the winter poles. Additionally, NASA’s CRISM instrument aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) has recorded the infrared counterpart of this emission: the O₂ (a¹Δ) emission at 1.27 µm.

This study aims to merge these two datasets (UVIS and CRISM) to create the most comprehensive map of nocturnal oxygen emissions on Mars to date. By integrating observations in both the visible and infrared domains, this novel approach will enhance our understanding of oxygen transport and distribution in the Martian atmosphere.

The final dataset will be compared to 3D global circulation models to provide unprecedented constraints on atmospheric dynamics, improving our knowledge of photochemical and transport processes on Mars.

How to cite: Soret, L., Lejeune, S., and Gérard, J.-C.: Mapping of the Atomic Oxygen Nightglow Emissions on Mars in the Visible and Infrared Domains, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-32, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-32, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

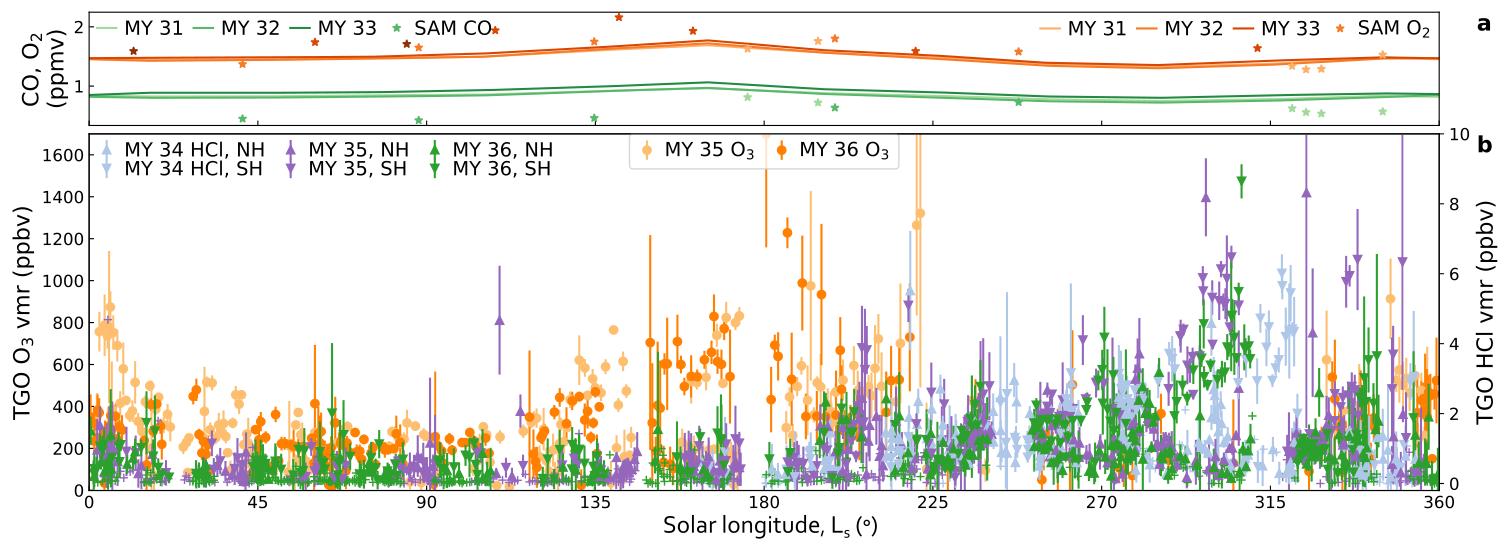

The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter has been operating around Mars since April 2018, amassing a wealth of knowledge about the atmosphere and surface of the Red Planet. Onboard are two spectrometer suites, NOMAD and ACS, a surface camera, CASSIS, and a neutron detector, FREND.

NOMAD consists of three spectrometers: two observe in the infrared, in the 2-4 µm region, and one observes the 200-650 nm region. The two infrared spectrometers [1] are named “SO”, which is designed for solar occultation observations, and “LNO”, which is primarily designed for nadir observations, but also can measure solar occultations and occasionally observes Phobos. The ultraviolet-visible spectrometer can do all the above: solar occultation, limb, nadir, and Phobos and Deimos observations [2]. At the time of writing all three spectrometers continue to operate nominally.

In this presentation we will give a summary of recent results and ongoing projects within the NOMAD team: results have recently been published looking at dust and aerosol particle sizes [3], water vapour pumping to high altitudes [4], ultraviolet and visible dayglow [5] and nightglow [6]; plus there are upcoming joint observation campaigns with the iSHELL instrument on IRTF, EUVM on MAVEN, and ACS (also on TGO). Also, the climatologies of the principal atmospheric constituents measured by NOMAD are regularly updated - for example ozone, water vapour, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide (for temperature and pressure retrievals), hydrogen chloride, water ice and CO2 ice clouds.

Acknowledgements

The NOMAD experiment is led by the Royal Belgian Institute for Space Aeronomy (IASB-BIRA) with co-PI teams from Spain (IAA-CSIC), Italy (INAF-IAPS) and the United Kingdom (Open University). This project acknowledges funding by: the Belgian Science Policy Office (BELSPO) with the financial and contractual coordination by the ESA Prodex Office (PEA 4000103401, 4000121493, 4000140753, 4000140863); by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCIU) and European funds (grants PGC2018-101836-B-I00 and ESP2017-87143-R; MINECO/FEDER), from the Severo Ochoa (CEX2021-001131-S) and from MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (grants PID2022-137579NB-I00, RTI2018-100920-J-I00 and PID2022-141216NB-I00); by the UK Space Agency (grants ST/V002295/1, ST/V005332/1, ST/X006549/1, ST/Y000234/1 and ST/R003025/1); and by the Italian Space Agency (grant 2018-2-HH.0). This work was supported by the Belgian Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique – FNRS (grant 30442502; ET_HOME).

References

- E. Neefs,. A.C. Vandaele , R. Drummond, I. Thomas, S. Berkenbosch, R. Clairquin, S. Delanoye, B. Ristic, J. Maes, S. Bonnewijn, G. Pieck, E. Equeter, C. Depiesse, F. Daerden, E. Van Ransbeeck, D. Nevejans, J. Rodriguez, J.-J. Lopez-Moreno, R. Sanz, R. Morales, G.P. Candini, C. Pastor, B. Aparicio del Moral, J.M. Jeronimo, J. Gomez, I. Perez, F. Navarro, J. Cubas, G. Alonso, A. Gomez, T. Thibert, M.R. Patel, G. Belucci, L. De Vos, S. Lesschaeve, N. Van Vooren, W. Moelans, L. Aballea, S. Glorieux, A. Baeke, D. Kendall, J. De Neef, A. Soenen, P.Y. Puech, J. Ward, J.F. Jamoye, D. Diez, A. Vicario, and M. Jankowski; NOMAD spectrometers on the ExoMars trace gas orbiter mission: part 1 - design, manufacturing and testing of the infrared channels. (2015) Applied Optics 54 (28), 8494- 8520

- M. R. Patel, P. Antoine, J. Mason, M. Leese, B. Hathi, A. Stevens, D. Dawson, J. Gow, T. Ringrose, J. Holmes, S. Lewis, D. Beghuin, P. Van Donink, R. Ligot, J.-L. Dewandel, D. Hu, D. Bates, R. Cole, R. Drummond, I.R. Thomas, C. Depiesse, E. Neefs, E. Equeter, B. Ristic, S. Berkenbosch, D. Bolsée, Y. Willame, A.C. Vandaele , S. Lesschaeve, L. De Vos, N. Van Vooren, T. Thibert, E. Mazy, J. Rodriguez-Gomez, R. Morales, G.P. Candini, C. Pastor-Morales, R. Sanz, B. Aparicio del Moral, J.-M. Jeronimo-Zafra, J.M. Gomez-Lopez, G. Alonso-Rodrigo, I. Pérez-Grande, J. Cubas, A. Gomez-Sanjuan, F. Navarro-Medina, A. Ben Moussa, B. Giordanengo, S. Gissot, G. Bellucci, and J.J. Lopez-Moreno; The NOMAD spectrometer on the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter mission: part 2—design, manufacturing and testing of the ultraviolet and visible channel . (2017) Applied Optics 56(10), 2771-2782

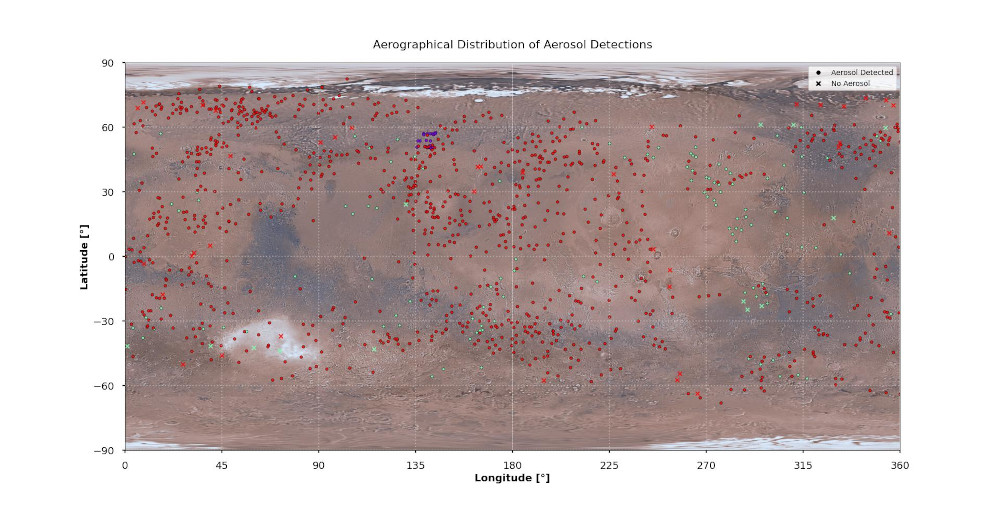

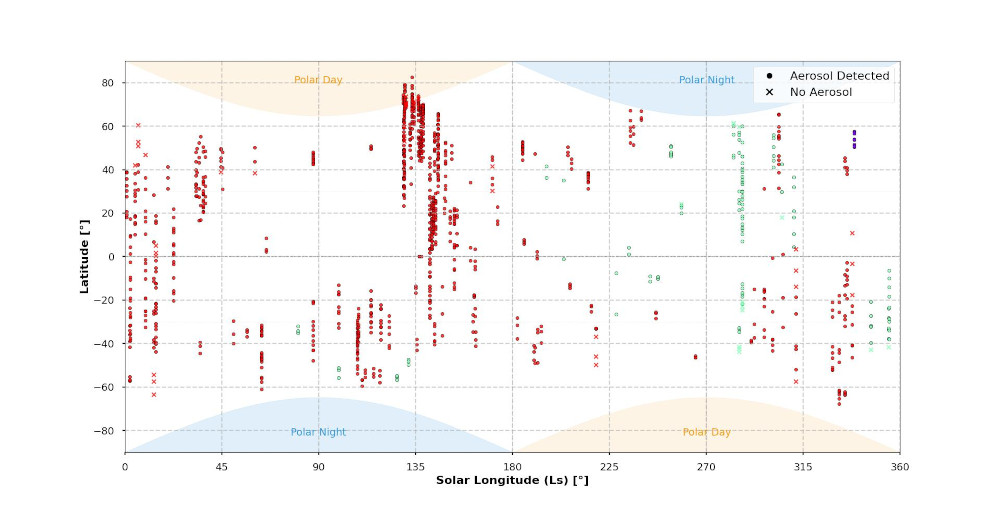

- Z. Flimon, J. Erwin, S. Robert, L. Neary, A. Piccialli, L. Trompet, Y. Willame, F. Vanhellemont, F. Daerden, S. Bauduin, M. Wolff, I. R. Thomas, B. Ristic, J. P. Mason, C. Depiesse, M. R. Patel, G. Bellucci, J.-J. Lopez-Moreno, A. C. Vandaele; Aerosol Climatology on Mars as Observed by NOMAD UVIS on ExoMars TGO (2025) J. Geophys. Res. Planets

- A. Brines, M A. López-Valverde, B. Funke, F. González-Galindo, S. Aoki, G. L. Villanueva, J. A. Holmes, D. A. Belyaev, G. Liuzzi, I. R. Thomas, J. T. Erwin, U. Grabowski, F. Forget, J. J. Lopez-Moreno, J. Rodriguez-Gomez, F. Daerden, L. Trompet, B. Ristic, M. R. Patel, G. Bellucci, A. C. Vandaele; Strong Localized Pumping of Water Vapor to High Altitudes on Mars During the Perihelion Season. (2024) Geophys. Res. Letters

- L. Soret, H. Robin, J.-C. Gérard, L. Gkouvelis, I. Thomas, B. Ristic, Y. Willame, B. Hubert, A. C. Vandaele, J. P. Mason, F. Daerden, M. R. Patel; The Martian oxygen green line dayglow: response to solar activity. (submitted to Icarus 2025)

- L. Soret, F. González-Galindo, J.-C. Gérard, I. R. Thomas, B. Ristic, Y. Willame, A. C. Vandaele, B. Hubert, F. Lefèvre, F. Daerden, M. R. Patel; Ultraviolet NO and Visible O2 Nightglow in the Mars Southern Winter Polar Region: Statistical Study and Model Comparison. (2024) J. Geophys. Res. Planets

How to cite: Thomas, I., Vandaele, A. C., Trompet, L., Aoki, S., Brines, A., Willame, Y., Piccialli, A., Hendrick, F., Flimon, Z., Daerden, F., Neary, L., Ristic, B., Robert, S., Gérard, J.-C., Mason, J., Lopez Valverde, M. A., Patel, M., and Bellucci, G. and the The NOMAD Team: The ExoMars 2016 Trace Gas Orbiter: Recent Results from NOMAD, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-484, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-484, 2025.

The observation of temporal and spatial variability in methane concentration on Mars is puzzling, as the current 300-year photochemical lifetime of methane should ensure that it is well mixed throughout the atmosphere (Atreya et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2003). For instance, the spectrometer onboard the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) rover has observed a significantly higher methane concentration near the surface of Mars than has been observed above 5 km by the instruments aboard the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO). Near the surface, MSL sees approximately a 0.4 ppbv concentration of background methane that varies on diurnal and seasonal timescales with periodic spikes of over 20 ppbv (Webster et al., 2018, 2021). By contrast, in the middle and upper atmosphere, no methane is observed by TGO to below the detection threshold of ~0.02 ppbv (Korablev et al., 2019; Montmessin et al., 2021).

Previously, these differences were explained by considering the different timing and airmasses being sampled by these measurements – at night and near the surface for MSL and at sunset or sunrise and at altitude for TGO (Moores, et al., 2019). This framework required that the methane decrease from its relatively high surface concentration to a much lower concentration at altitude. While this is possible purely through atmospheric mixing and dilution, if the amount of methane being injected into the atmosphere near the surface is sufficiently large this methane will eventually build up in the upper atmosphere.

In this work, we consider the effect of a recently quantified destruction mechanism described by Zhang et al., (2022). Their derived destruction rates using a simplified model of the atmosphere suggest that methane adsorbed onto a surface with UV-activated perchlorate can contribute to the destruction of methane on the order of hours to days. This model is appealing for several reasons: (1) it can rapidly destroy methane, (2) it operates only during the day when both MSL and TGO observe methane to be low and not at night when MSL observes methane concentration to be high, and (3) destruction occurs on the surfaces of dust grains which are in abundance in the lower atmosphere. To evaluate the effects of this destruction mechanism with a more realistic representation of the Martian atmosphere, we couple its effects into a martian vertical diffusion model (VDM) that was previously developed by Walters et al (2024).

Walters et al. (2024) previously investigated methane flux from the surface of Mars in a 1-D VDM that incorporated eddy diffusivity coefficients derived from GEM-Mars, a global climate model, to model the effects of transport and diffusion of methane in the VDM (Neary & Daerden, 2018; Stroud et al., 2005). The methane is injected at the surface, and the methane mixing ratio is tracked throughout the vertical column using 1 m layers in half-hour time steps for select sols. While Walters et al. (2024) were able to closely replicate the required flux to replicate the SAM-TLS measurements, the diffusion and removal at the top layer was insufficient to decrease methane below 0.02 ppbv at the top of their model at 5 km above the surface.

As part of the inclusion of a destruction mechanism in the VDM simulation procedure (Fig. 1), we made the following changes to the model of Walters et al. (2024): (1) we incorporated a Conrath profile to describe the dust distribution in the atmosphere (Conrath, 1975), (2) we added in a radiative transfer model to estimate the available UVC for the destruction mechanism (Smith & Moores, 2020) at each step in the VDM, and (3) we also added a simple box model on top of the VDM to track the methane concentration in the portion of the atmosphere that is visible to TGO. Diffusion into this upper box is dependent on the relative concentration of methane in the top layer in the VDM and the box.