- 1Planetary Science Institute , United States of America (gareth.morgan.uk@gmail.com)

- 2National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, United States of America

- 3Lunar and Planetary Institute, United States of America

- 4Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, United States of America

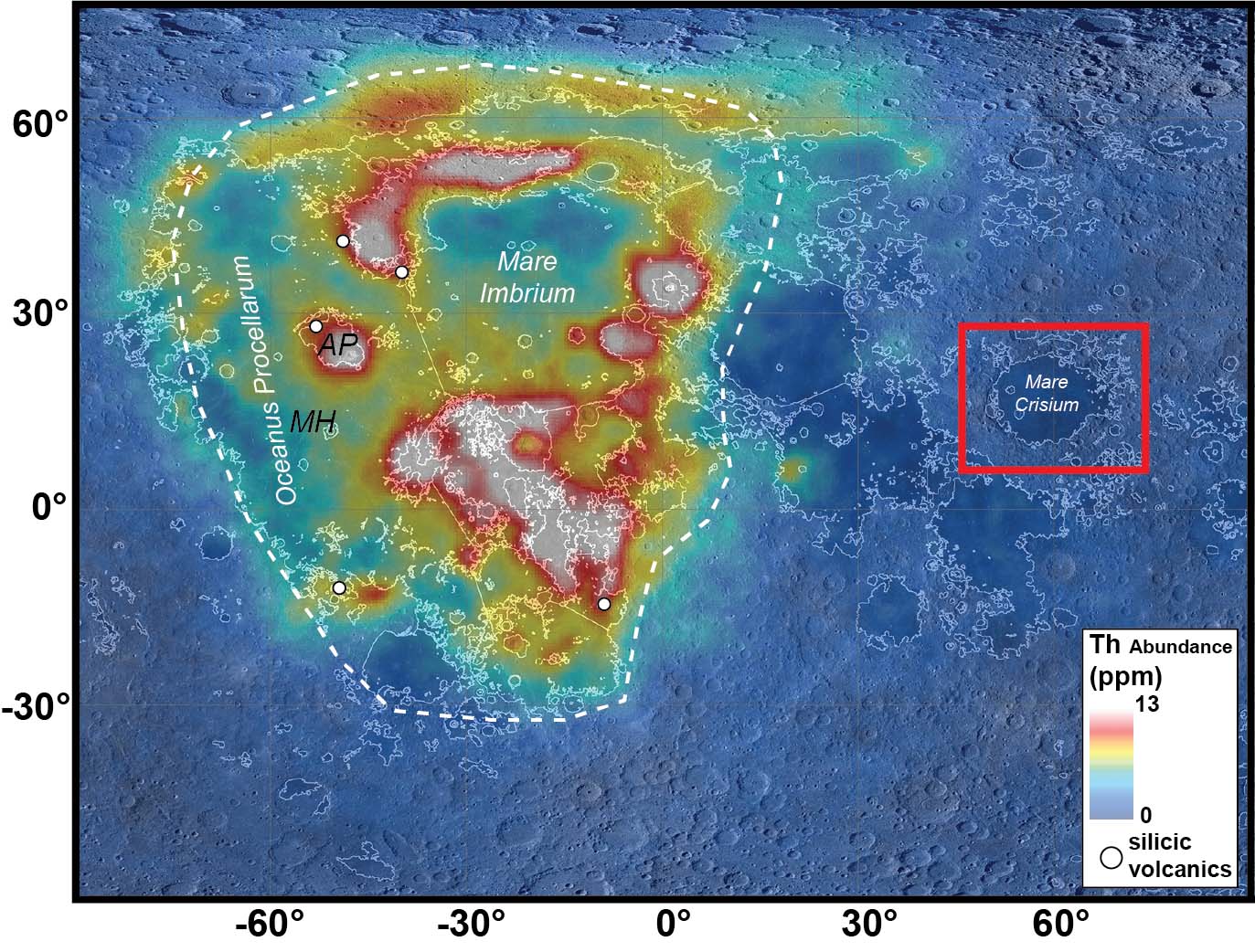

Motivation: The prevailing explanation for the dramatic asymmetry in lunar volcanism is that the Procellarum KREEP Terrane (PKT) represents a unique lunar province hosting a shallow reservoir of heat-producing elements. But is the story more complex? Isolated from other mare deposits within the Nectarian-aged Crisium Basin (Figure 1a), the 550 km-wide Mare Crisium and surrounding mare units offer a critical non-PKT reference point for exploring just how unique PKT volcanism really was (Figure 1).

The Crisium region hosts a surprisingly diverse range of volcanic structures and deposits. In addition to flood basalts, the region contains volcanic cones, such as Mons Latreille [1], domes [2], and as we will present, potential pyroclastic deposits and well-preserved flow features not reported elsewhere on the Moon (Figure 1). This complex assemblage of volcanic features suggests that a range of eruptive styles—from effusive to explosive—occurred throughout the basin’s history. This region was also the landing site of the recent Firefly Aerospace Blue Ghost Mission 1.

Figure 1. Th abundance from Lunar Prospector (Lawrence et al., 2007) showing concentrated values within the PKT (white dashed region). The major volcanic regions within the PKT are highlighted (AP = Aristarchus plateau, MH = Marius Hills) as is the Crisium region.

Investigations: Leveraging the diverse array of available orbital data sets, we will present the results of an integrated approach to analyzing the Crisium Region. A major focus of our cross-dataset analysis is the use of multi-wavelength radar data (4.2 – 70 cm) from the Mini-RF instrument on Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter [5] and Earth-based radar observations [e.g. 6]. Radar analysis enables both the surface and the underlying regolith to be interrogated, revealing surface/subsurface boulder distributions, near-surface structure, and TiO2 content of lunar basalts. Due to the range of TiO2 content within Mare Crisium and–as we will present–the occurrence of pyroclastic deposits (which exhibit unique signatures in radar data), radar is particularly useful in delineating eruption events and styles. Radar data has also proven critical in assessing engineering concerns regarding landing site selection.

Additionally, we are in the second year of a four-year Lunar Data Analysis Program project to produce a 1:1,000,000 scale map of the Crisium basin region. The study area is defined by 46°E to 73°E and 6°N to 28°N and incorporates Mare Crisium, the major Crisium basin structure and surrounding small mare units including Mare Undarum and Mare Anguis.

Results and interpretation: Our new analysis has enabled a radar-based compositional delineation of Mare Crisium and provided a fresh perspective on the eruptional history of the basin’s eastern portion.

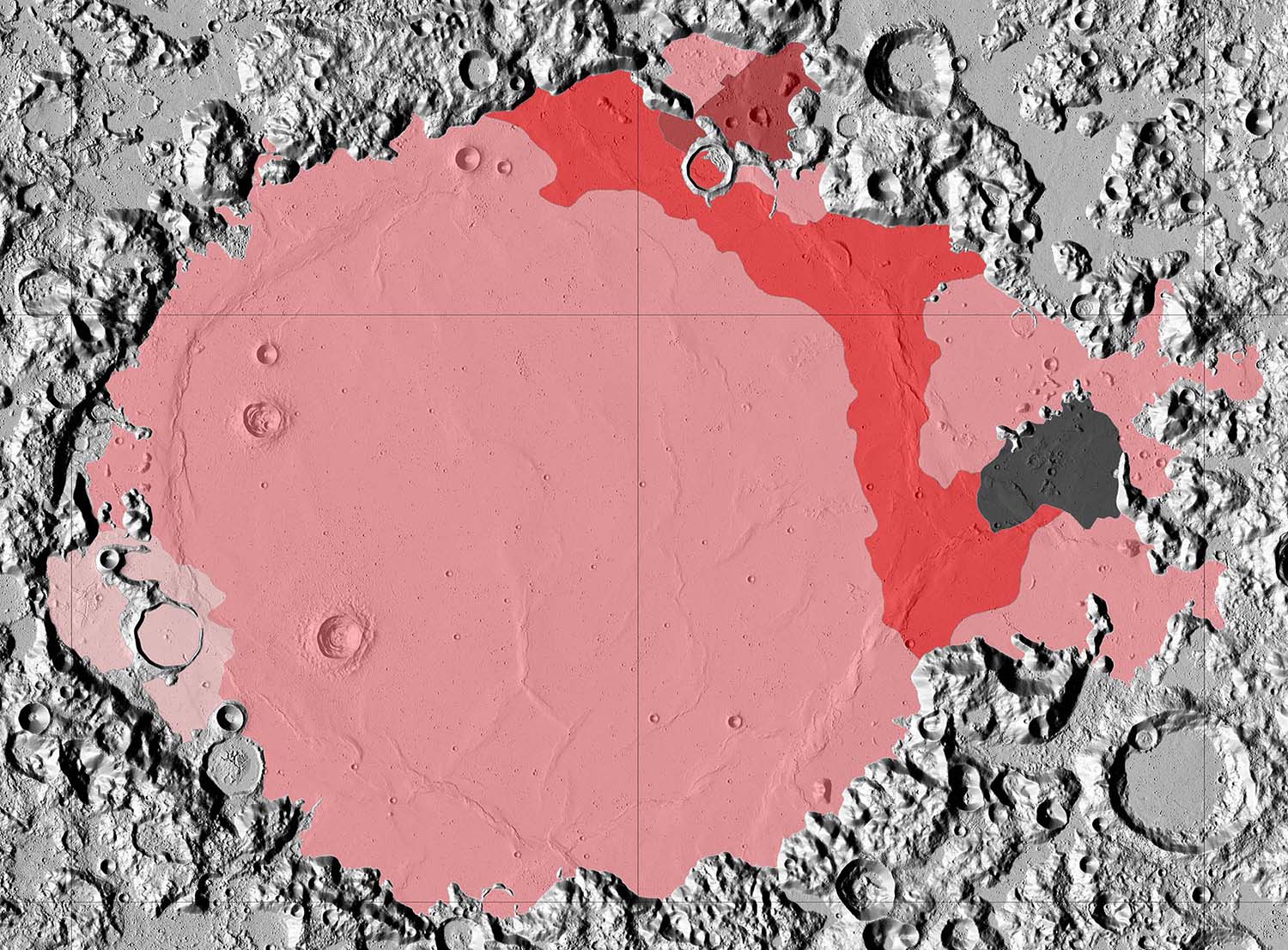

Mare Units: Earth-based 70 cm radar mapping reveals broad variations in backscatter that suggest at least five distinct mare units (Figure 2). These units show some alignment with the most recent mapping effort [1], particularly in the east, but the radar data also highlight potential unit boundaries that were previously mapped as broad ejecta using UV-NIR datasets.

Figure 2. 70 cm radar based map of mare units within Mare Crisium.

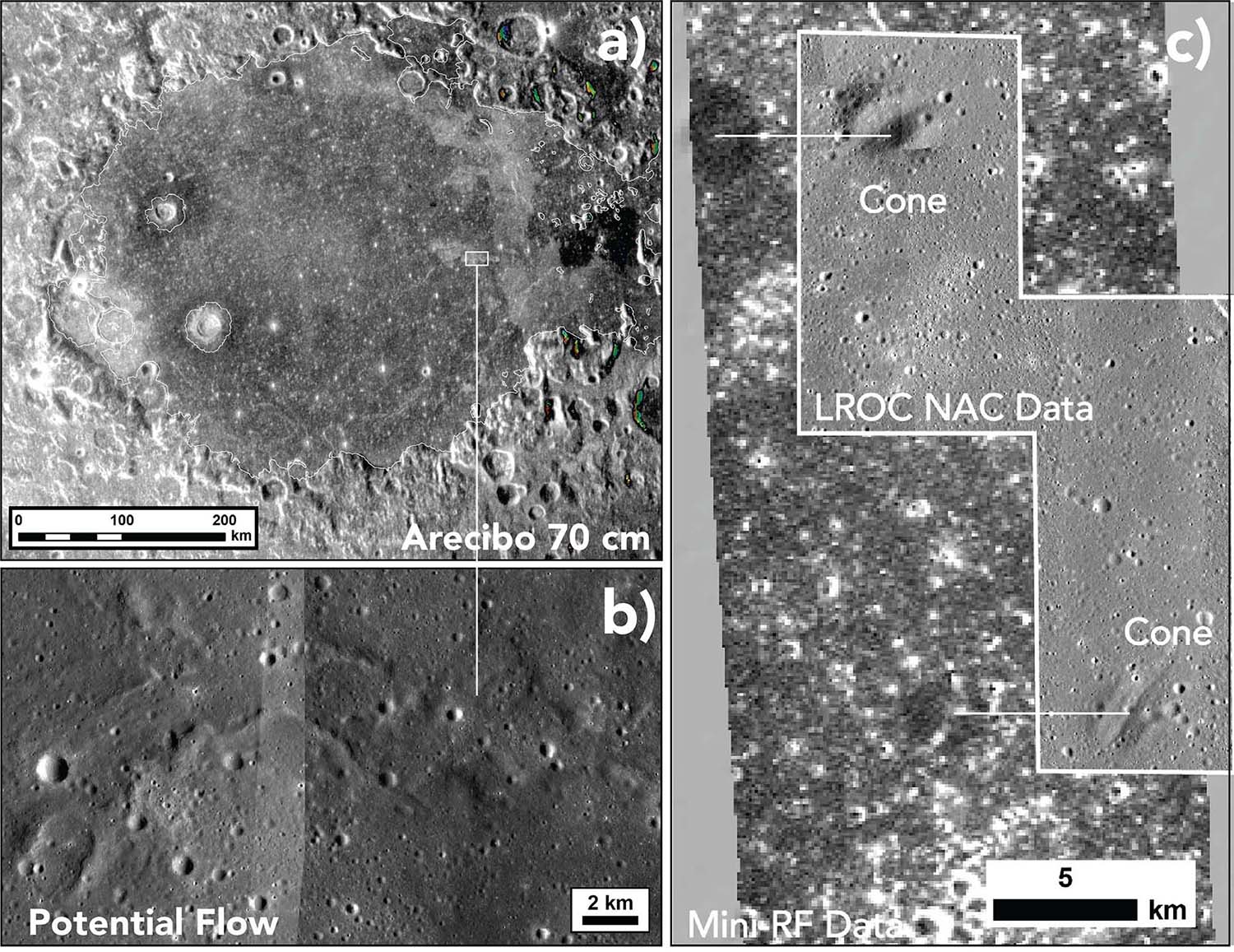

Explosive Eruptions: All radar wavelengths reveal a reduced backscatter response associated with volcanic cones (Figure 3). The absence of centimeter-scale scatterers suggests the presence of previously unrecognized small-scale pyroclastic deposits. If this interpretation is correct, it implies that these cones differ from terrestrial cinder cones (which would generate a significantly brighter backscatter response), pointing to an explosive component in the eruptions that formed them.

Figure 3. Radar coverage of volcanic structures within Mare Crisium. (a) Earth-based 70 cm coverage. Note that distinct differences in backscatter delineate individual units within the mare. (b) LROC NAC images of unusual radar bright flow feature. (c) Mini-RF 4.2 cm coverage of cones (see LROC NAC image for context). Note the cones exhibit a very low backscatter response consistent with pyroclastic materials.

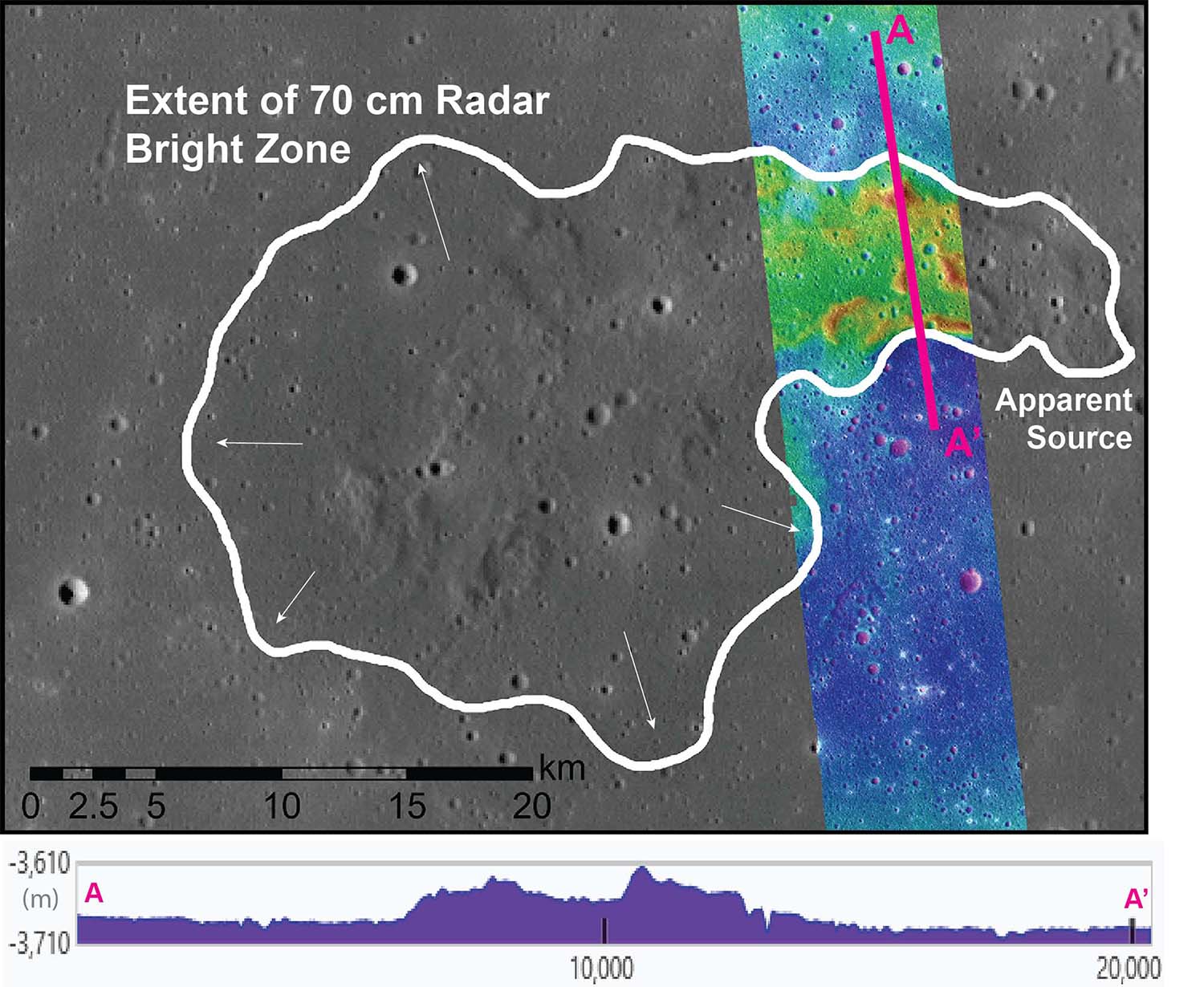

Individual Flow Units: In contrast to Earth, Venus, and Mars, most individual mare flow morphologies are subdued—due in part to the low eruptive magma viscosity and the associated thin nature of lunar lava—and are thus masked by the impact-generated regolith. A few exceptions exist, such as the extensive, young flows in central Mare Imbrium, situated within the PKT. There, 70 cm radar-bright features elongated perpendicular to the broad local slope (east-west) are clearly identifiable (Figure 3). Inspection of the corresponding LROC NAC images reveals these features to have rough textures that broadly resemble platy terrestrial or Martian lava flows and appear to be sourced from cone-like structures (Figure 4).

Figure 4. LROC WAC image of the northernmost potential flow feature. Note to the west, the radar signature extends beyond the topographic signature of the flow. The arrows highlight the direction and location of potential breakouts. Topo profile from LROC NAC stereo DTM.

Further comparison of image, topographic, and radar data indicates that these potential flows are ~30 m thick with higher-standing levees. The rugged nature of the flows suggests deflation, while the edges display smooth, radar-bright lobes that may represent breakouts. The elevated 70 cm backscatter could reflect a localized increase in blocky material on the surface and suspended within the regolith. We interpret these features as individual lava flows that have not been as fully degraded by impact gardening as typical mare flows. Their distinct morphology relative to the Imbrium flows suggests a different rheology, indicating that different eruption conditions have occurred across the mare.

References: [1] Lu et al., 2021, Remote Sens. 13(23), 4828. [2] Lina et al., 2008, Planetary and Space Science, 56, 3–4, 553-569 [3] Spudis, and Sliz., 2017, J. Geophys. Res. Lett., 44, 1260–1265, doi:10.1002/2016GL071429. [4] Runyon et al., 2020, J. Geophys. Res. 125, e2019JE006024. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JE006024 [5] Patterson et al., 2017, Icarus, 283, [6] Campbell et al., 2007, IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing, 45, 12, DOI: 10.1109/TGRS.2007.906582.

How to cite: Morgan, G., Weitz, C., Berman, D., Jawin, E., Russell, M., Campbell, B., Stopar, J., Patterson, G., and Stickle, A.: Unveiling Lunar Volcanic Complexity Beyond the Procellarum Kreep Terrane, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1058, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1058, 2025.