- 1University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA.

- 2University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA

- 3UCLA, Los Angeles, CA, USA

- 4Space Science Institute, Boulder, CO, USA

Introduction: Layers within the martian North Polar Layered Deposits (NPLD) have long been thought to contain a climatic record akin to terrestrial ice cores [1]. The NPLD likely wax and wane in thickness with variations in Mars’ orbit and obliquity; however, strong local effects on erosion and deposition patterns can also be seen. Spiraling troughs pervade the NPLD interior and have migrated poleward [2]. Chasma Boreale has persisted throughout NPLD history while other similarly large depressions have been filled in by accumulation [3].

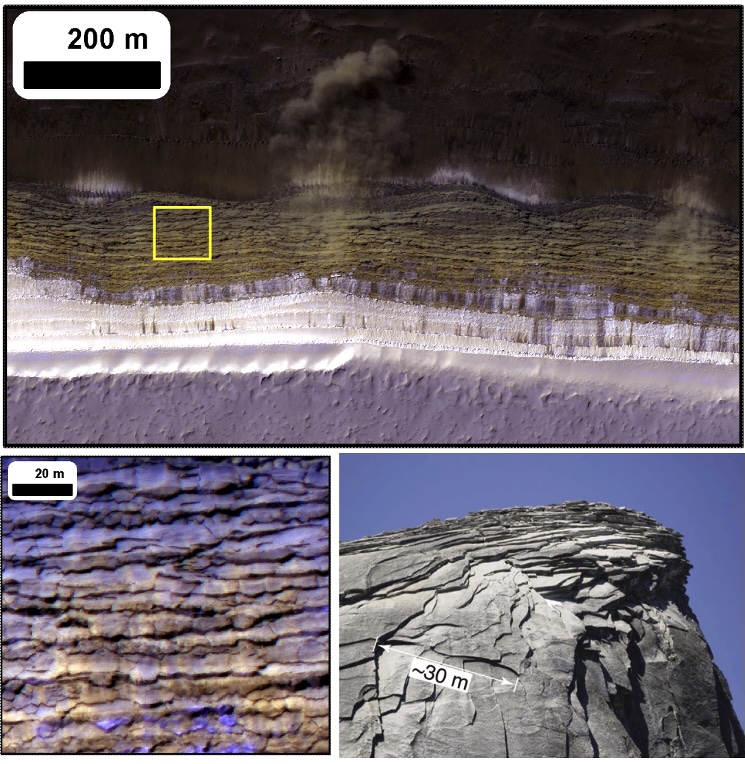

Along part of their margins, the NPLD are bounded by near-vertical scarps of up to 800 m in relief (Figure 1). These scarps typically overlie exposures of a sandy basal unit [4-5]. Removal of this friable material may be undermining the NPLD [6] and counteracting the shallowing effects of viscous relaxation [7]. These scarp faces appear heavily fractured with jagged slab-like fragments (Figure 1) and lack the thicker slumping dust covers seen on the troughs [12].

Figure 1. HiRISE image (PSP_007338_2640, Ls 34) of 70° scarp at 84°N 235°E with avalanche in progress [11]. Yellow box shows location of scarp texture in bottom left. A granite dome in Yosemite Valley [16] shows sheeting joints at a similar scale in the bottom right.

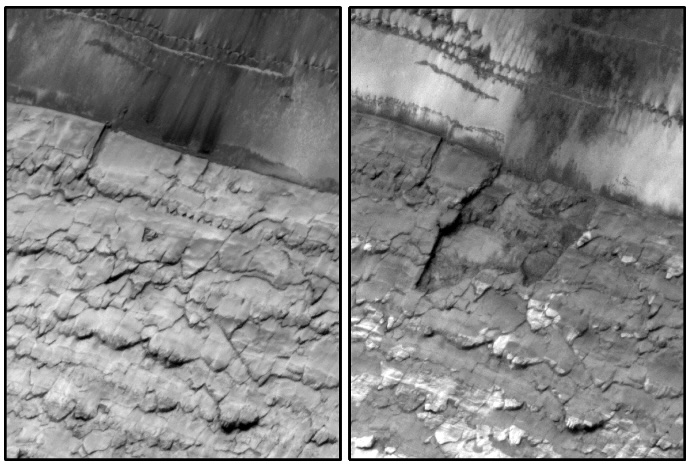

Evidence for mass wasting of these steep cliffs is common. Frequent frost and dust avalanches (Figure 1) are observed by HiRISE in early spring (Ls 0-50) each year [6, 11,17]. Blockfalls also occur often, as evidenced by fresh basal debris and scarp changes [8-10]. Many changes are difficult to resolve on these near-vertical scarps, but exfoliation of large slabs (Figure 2) indicates the prevalence of sheeting joints in addition to fractures perpendicular to the scarp surface.

Figure 2. HiRISE images ESP_016292_2640 (left) and ESP_024639_2640 (right) show collapse of a 70m wide slab during MY30.

Here, we examine the unique thermal environment of these scarps and the thermally generated stresses they endure. We find tensional fractures are easily generated and that compression, combined with scarp-curvature, can lead to sheeting joints and exfoliation of slab-like fragments in a process that has terrestrial analogs on granitic domes (Figure 1). We hypothesize that avalanches are caused by blockfalls and compare their seasonality to thermal stresses.

Thermomechanical Behavior: We simulated the thermal behavior of these steep scarps assuming they are water ice overlain by a negligible dust cover. Their steepness means that they exchange reflected and emitted radiation with surrounding flat terrain as well as open sky. We separately simulated the temperatures of the surrounding terrain (assumed to be dark sand when defrosted) to calculate the upwelling fluxes onto the scarp face. Near-vertical polar surfaces have similar illumination geometries to flat terrain at the equator, but with much larger atmospheric path lengths (Figure 3) making their heating sensitive to interannually-variable aerosols. We calculate scarp and flat surface heating with a 16-stream pseudospherical radiative transfer model.

Figure 3. Polar scarp and equatorial illumination near equinox.

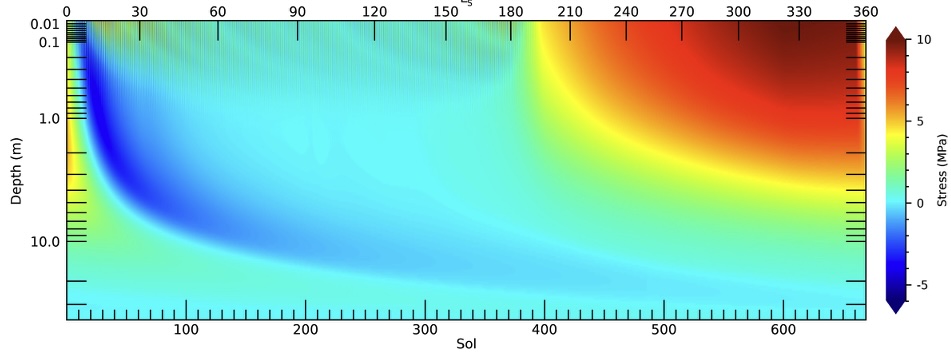

We follow the approach of [13] to calculate time varying stresses in an initially unfractured viscoelastic solid undergoing thermal expansion and contraction. No lateral strain can occur, so surface-parallel elastic stresses are created that decay due to grain-size-dependent viscous effects. Zenner pinning [14] with NPLD dust abundances [15] constrain ice grain sizes to be 10–1000 microns. During much of the northern summer, shallow diurnal temperature oscillations drive surface stress that alternate between extensional and compressive (Figure 4). At depth, compressional stresses occur during warmer periods and are thus more-effectively viscously relaxed. Colder ice allows for greater extensional stress during polar night.

Figure 4. Thermoelastic stresses (positive is tension) on a SW-facing 70° slope as a function of depth and season. Ice grain size is 100 microns.

Discussion: These steep scarps with thin dust covers cannot remain unfractured. Peak extensional stress exceeds water-ice strength to depths of meters (Figure 4). Once fractures have formed, surface-parallel strain is possible (through opening/closing of cracks) reducing extensional stresses. Fracture spacing should decrease until all points on the scarp face are near enough to a crack to avoid further fracturing from this mechanism [18].

In addition to these fractures, surface-parallel compression, in concert with surface curvature, can generate extensional stresses below (and normal to) the surface [16]. On terrestrial granitic domes, these result in surface-parallel sheeting joints and rockfalls. High compressional stresses on these martian scarps are relatively easy to generate, so only modest surface curvature (calculated from HiRISE stereo DTMs) is required. Peak compressive stresses (Figure 4) and sheeting joint formation occur in the upper meters in early spring, seasonally coinciding with avalanches.

Tensional and compressional stresses can thus divide the scarp face into disconnected slab-like sections that can fall 100s of meters and generate an avalanche of dust and debris en route. The seasonality of the compression wave that descends into the subsurface (Ls 0-50) matches the that of the avalanches [11,17] lending support to a stress origin for the avalanches although other mechanisms have been proposed [11].

References: [1] Byrne, Ann. Rev. Earth & Planet. Sci., 2009. [2] Smith et al., Nature, 2010. [3] Holt et al., Nature, 2010. [4] Byrne & Murray, JGR, 2002. [5] Fishbaugh & Head, Icarus, 2005. [6] Russell et al., LPSC, 2012. [7] Sori et al., GRL, 2016. [8] Fanara et al. 2020, Planet. Space Sci. 180, 104733. [9] Fanara et al. 2020, Icarus 342, 113434. [10] Su et al. 2023, Icarus 390, 115321. [11] Russell et al., GRL, 2008. [12] Herkenhoff et al., Science, 2007. [13] Mellon, JGR, 1997. [14] Durand et al., JGR, 2006. [15] Grima et al., GRL, 2009. [16] Martel, GRL, 2011. [17] Russell et al. 2024, 8th Intl. Mars Polar Conf. [18] Mellon et al., JGR 113(E4), 2008.

How to cite: Byrne, S., Shore, G., Landis, M., Russell, P., Sutton, S., Akers, K., and Wolff, M.: Stressful Times at the North Pole of Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1063, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1063, 2025.