- Southwest Research Institute, Solar System Science and Exploration Division, Boulder, United States of America (raluca@boulder.swri.edu)

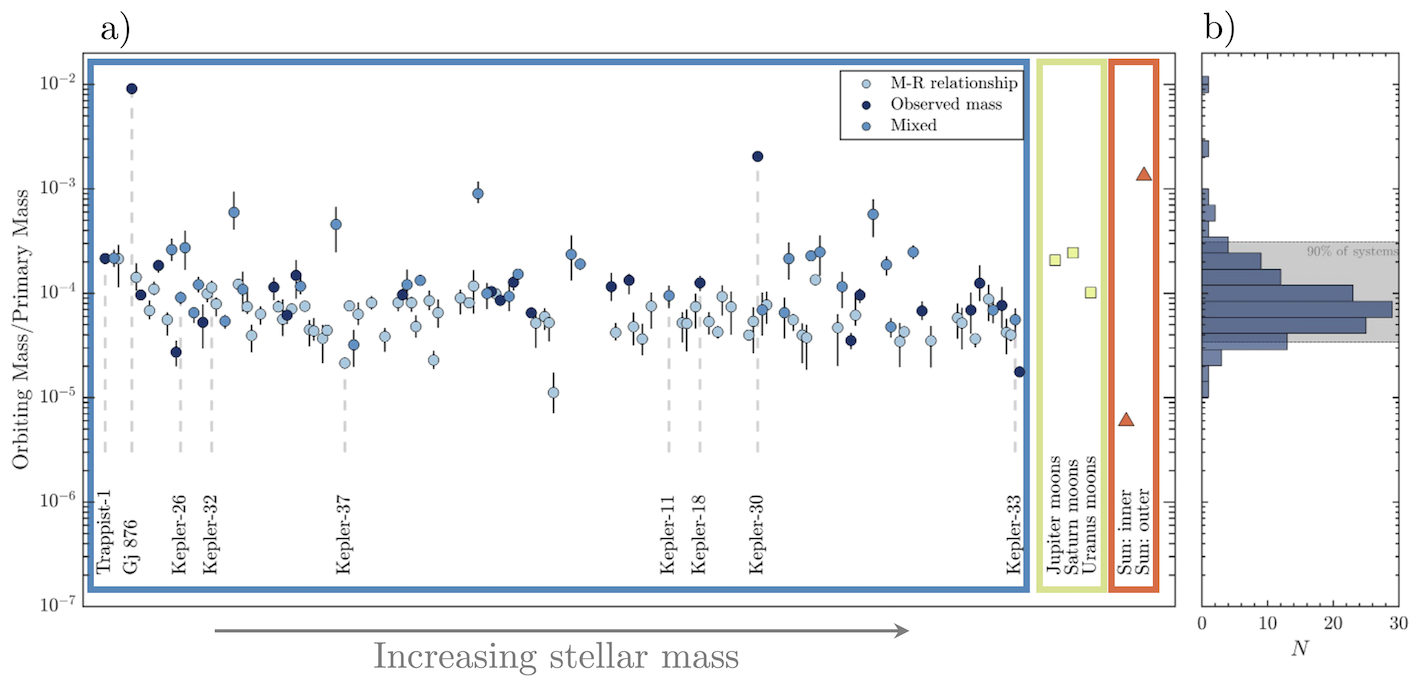

A surprising discovery in exoplanetary science has been compact systems of Earth to super-Earth sized planets orbiting within ∼ 10-2 to 10-1 au from their star, a region lacking planets in our Solar System. While compact systems are common, their origin is debated. A prevalent assumption is that compact systems formed after the infall of gas and solids to the circumstellar disk ended. However, observational evidence suggests accretion commences earlier. We propose that compact systems are surviving remnants of planet accretion during the end stages of infall (Rufu & Canup, 2025, Nature Communications, in press). This early accretion condition leads to a characteristic planetary system-to-star mass ratio, offering a compelling explanation for the remarkably similar ratios observed in known compact systems (Fig. 1).

We simulate the accretion of planets using an N-body code that includes a time-dependent infall of gas and solids, with a rate that decays exponentially on a timescale, τin, as well as gas disk interactions modeled with an exponentially decaying surface density characterized by a timescale τg.

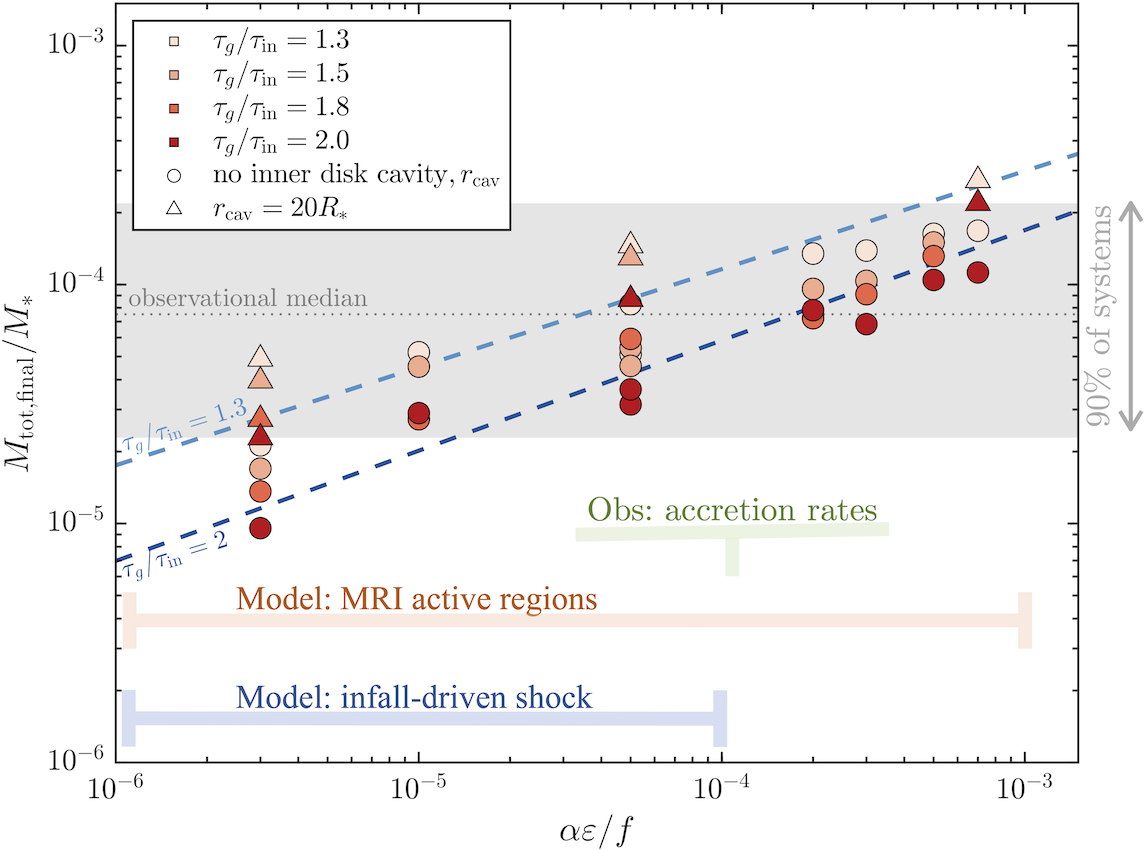

The mass of a planet that accretes within a disk region undergoing infall is regulated by a balance between mass growth due to accretion of infalling solids, and inward gas-driven orbital migration that becomes faster as the planet grows. This balance selects for similarly-sized planets whose mass is a function of infall and disk conditions. We show that the infall-produced planets survive until the gas disk disperses and migration ends, and that across a broad range of conditions, the mass of surviving systems is regulated to a few ⊗10-5 to 10-4 times the host star's mass (Fig. 2). Additionally, these simulations predict a relatively weak dependence of planet and planet system mass on stellar metallicity. This appears consistent with the nearly equal occurrence of warm super-Earths around stars of wide-ranging metallicities (Petigura et al, 2018) that has been unexplained.

Whether planets that form during infall survive depend on the radial extent of disk infall, rc, and the ratio of the gas disk lifetime to the infall timescale, τg /τin. Here we focus on small rc, and small τg /τin cases, consistent with compact systems. However, rc depends sensitively on the angular momentum of the parent cloud core and interactions of infalling material with the disk and stellar magnetosphere, so that even stars with similar masses may have substantially different rc values, resulting in different system architectures. For larger rc, long accretion timescales in the outer infall region may promote the formation of giant planets after infall has ended. Larger systems will also have larger τg /τin due to their longer gas disk lifetimes (Schib et al. 2021), implying that surviving inner planets that accreted during infall would have a lower total mass compared to the star. Most broadly, our results suggest that the long-standing assumption that planet accretion commences only after infall has ended may not be valid for all systems, and consideration of this early accretionary phase is warranted.

Fig 1 caption - Estimated total mass of transiting compact systems, Mtot, scaled to the stellar mass, M*. a, (Mtot/M*) for compact systems having ≥3 known planets that orbit a single star within a<0.5 au (circle markers, blue box). Points are ordered left-to-right by ascending stellar mass. Data are from www.exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu. For cases without mass estimates, we use the observed planet radius, increase the estimated radius uncertainty by a factor of 2, and then apply a radius vs. mass relation (Weiss & Marcy 2014). Light [medium] blue circles are systems with all [some] planetary masses estimated from this relation, while dark blue circles are systems with measured planetary masses. We include only systems with resulting errors ΔMtot /Mtot<1. b, Distribution of compact system mass ratios. Over a wide range of stellar masses ( M*~0.1 to 1.3 stellar mass), compact multi-planet systems display a common mass ratio, with 90% of systems having 3⊗10-5<(Mtot/M*)<3⊗10-4 (gray shaded region). This mass ratio is more similar to that of the gas giant satellite systems (square markers, yellow box) than to the inner or outer planets in our Solar System (triangle markers, red box).

Fig 2 caption - Results of planet accretion simulations with varied disk and infall properties. Final planetary system mass scaled to the stellar mass (1Msun ) as a function of (αε/ƒ) (α is the viscosity parameter, ε is the fraction of infalling solids incorporated into planets, and ƒ is the infall gas-to-solids ratio). The infall rate decays with timescale τin =5⊗105 yr, while the gas disk disperses over a longer timescale, τg =1.3 to 2τin (colors, legend). The simulations assume either an inner disk cavity with radius rcav=20R*~0.13 au (triangles) or no cavity (circles). Grey region shows range for 90% of observed compact systems shown in Fig. 1. Dashed lines show analytical predictions for the no-cavity case with τg/ τin=1.3 (light blue) and τg/ τin=2 (dark blue). Horizontal bars show plausible viscosity ranges based on observed stellar accretion rates (Hartmann et al. 1998), models of magnetorotational instability (MRI, Jankovic et al. 2019) and infall-driven shocks (Lesur et al. 2015), assuming ƒ/ε=102.

Fig.1

Fig. 2

How to cite: Rufu, R. and Canup, R.: Origin of compact exoplanetary systems during disk infall, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1153, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1153, 2025.