- 1University of Arizona, Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, United States of America (lmcarter@arizona.edu)

- 2Intuitive Machines

- 3Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory

Introduction:

The lunar south polar region has a complex evolutionary history encompassing multiple impacts as well as the trapping of water ice and other volatiles. The stratigraphic sequence of impact and basin ejecta, volcanic deposits, volatiles, and other more-local process such as mass wasting is poorly understood in many areas of the poles. Age dating of large craters [1,2] and areas of light plains [3] demonstrates the complex sequence of impact basin and crater overprinting. In particular, [3] demonstrate that the smooth “light plains” units across the south pole have clusters of ages indicating deposition associated with Schrödinger and Orientale basins, Shackleton crater, and some local events.

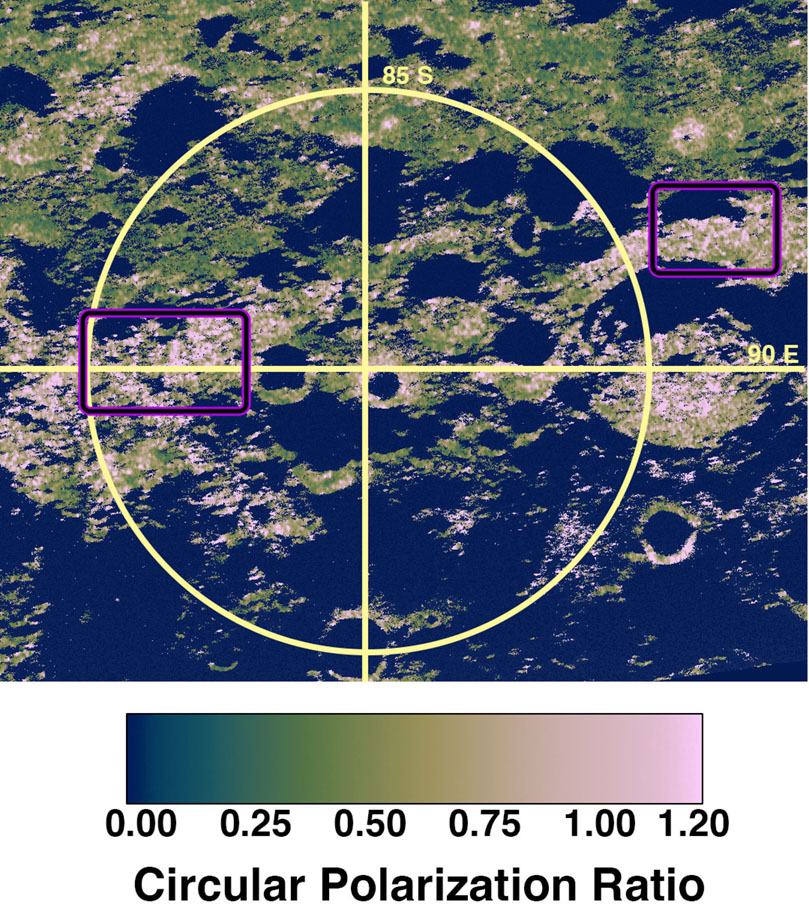

Radar data can be used to help understand the surface and subsurface structure of the regolith. S-band radar waves penetrate about a meter, and P-band radar can reach several meters depth in lunar materials. Prior radar observations of the lunar south polar region revealed relatively radar-bright areas with high circular polarization ratio values (CPR) [4,5]. CPR is the ratio of the same sense polarized wave that was transmitted over the opposite sense polarized wave and is often used as a measure of roughness. Areas mapped as light plains have high CPR values and were interpreted as fluidized ejecta from basin impacts [4]. Some young impact craters also have very high CPR values, which could possibly be due to excavated rocks from a basin ejecta melt layer under the surface [5].

In this work we focus on tens-of-kilometer diameter craters and areas of light plains. These regions have moderate to high CPR values in P-band radar data that imply a component of scattering from abundant rocks that could be in the surface or subsurface (Figure 1). Understanding the regolith layering and the surface rock abundance will help us better determine their origin and relative sequence, especially in the areas of light plains where age dating is challenging due to equilibrium conditions [3].

Figure 1: Arecibo Observatory P-band image of the lunar south pole. The image is colorized CPR overlaid on a total power image. The purple outlined boxes show the locations of the smooth plains investigated in this study.

Comparing optical images and radar datasets:

Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter ShadowCam observations provide an opportunity to investigate the morphology and reflectance of areas that are permanently or intermittently in shadow [6] and to map features across both sunlit and shadowed areas. We use ShadowCam images with multiple lighting geometries to map surface rocks, surface textures, and evidence of mass wasting. In areas of smooth plains, the lighting geometry can be particularly difficult due to their complex topography and relatively low elevation. We use mosaics of some of these areas to better track features over larger areas.

Radar observations are available from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Mini-RF instrument (12.6 cm wavelength, S-band), and Arecibo Observatory (12.6 cm wavelength, S-band, and 70 cm wavelength, P-band) with different viewing geometries. The wavelength of the radar data affects the scattering behavior – longer wavelengths will penetrate deeper and are less sensitive to smaller cm-sized rocks. CPR images are available for all three datasets.

Results and Discussion:

The areas of mapped light plains with high CPR values have very different surfaces from similar high-CPR valued fresh impact craters. The fresh impact craters have extremely rugged ejecta blankets and interiors as shown in ShadowCam images. The slopes and interiors of Wapowski and Hale Q craters have landslides and extended areas of surface rocks (Figure 2). The rocks have sizes ranging from near the detection limit of the ShadowCam images (~2 m) to ~ 30 m in diameter. They are found on top of hummocky surfaces in the crater interior, exposed in crater walls, and exposed in patches or layers within larger hummocks. There are also extensive lineations on the floor hummocks, possibly from mass wasting and slumping of regolith. The rocks and surface textures create a very rough surface from the centimeter to decimeter scale, likely explaining the high CPR values measured at both S-band and P-band.

Figure 2: ShadowCam image of the interior of Hale Q crater showing abundant large surface rocks and lineated surface texture (especially lower left). Image M022457496S.

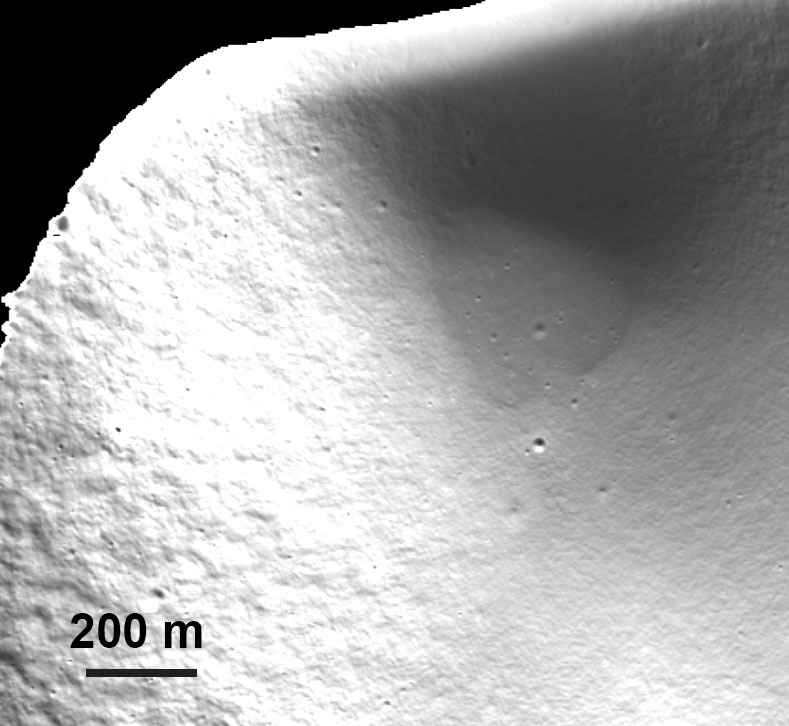

In contrast, light plains regions north of de Gerlache (-85.9°, 270° E) and northeast of Amundsen crater (-83.4°, 65.7° E) have many small (meters to tens-of meter diameter) impact craters but very few visible surface rocks. These relationships suggests that the high CPR values are produced by a buried rough surface, buried rocks, or surface rocks below the ShadowCam detection limit. The abundance of small impact craters in these light plains areas suggests that they are comprised of a rock layer or layers that are different from the nearby highlands. This layer could be the result of basin ejecta or ejecta deposits from nearby craters [3], which could have been deposited as a molten or partially molten deposit. Interestingly, some small craters south of Drygalski have ponded material in their floors (Figure 3), similar to melt ponds previously identified by [7]. Lunar impact melts have previously been found to have very high CPR values, probably due to the surface structure of the cooled melt [8,9]. Current work involves mapping changes in surface texture across the light plains regions, including mapping of possible impact melt deposits.

Figure 3: ShadowCam image showing a flat floor in a topographic depression that could be ponded impact melt. Image M047084443S.

References:

[1] Tye et al. (2015), Icarus, 255, 70-77, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2015.03.016.

[2] Deutsch et al. (2020), Icarus, 336, 113455, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113455

[3] Giuri, B. et al (2024). JGR, 129, e2024JE008605, doi: https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JE008605.

[4]Campbell B. A. and Campbell D. B. (2006), Icarus, 180, 1-7, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2005.08.018.

[5] Campbell B. A. et al. (2018), Icarus, 314, 294-298, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.05.025.

[6] Robinson M. S. et al. (2023), JASS, 40(4), 149-171, doi: 10.5140/JASS.2023.40.4.149.

[7] Robinson, M. S. et al. (2016), Icarus, 273, 121-134, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2015.06.028.

[8] Carter et al. (2012), JGR, 117, E00H09, doi:10.1029/2011JE003911.

[9] Neish, C. D. et al. (2021), Icarus, 361, 114392, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114392.

How to cite: Carter, L., Grieser, S., Robinson, M., Mahanti, P., Denevi, B., and Kinczyk, M.: Mapping the surface and subsurface structure of rugged impact crater and basin ejecta near the lunar south pole, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1197, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1197, 2025.