Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

TP3

This session aims at understanding planetary impact processes at all scales, in terms of impact cratering and ejecta dynamics, crater distribution and crater chronology, material mixing, shock metamorphism and other geochemical consequences, ejecta-atmosphere interactions, impact induced climatic and environmental effects, and biotic responses.

We welcome oral and poster presentations across this broad range of studies about natural or artificial impact collision phenomena on planetary surfaces and small bodies. In particular, abstracts on impact modelling, impact laboratory experiments, geologic and structural mapping, petrographic and geochemical analysis of impact products, as well as remote sensing observations from space missions to planets and small bodies. We also welcome the examination of competing hypotheses for the giant impact formation of terrestrial and outer solar system bodies.

Session assets

Introduction: Calcite is a ubiquitous mineral at the earth’s surface. While shock effects for most of the rock-forming silicates have been intensely studied and calibrated experimentally against shock pressure, unambiguous shock effects for calcite, are rare. Thus, calcite has a currently overlooked potential as an indicator for shock deformation. Here we examine the potential of high twin densities as a shock effect in calcite.

Methods: A 25 cm cube of Carrara Marble was selected as target material. A two-stage light gas gun at the Fraunhofer Ernst-Mach-Institute for High-Speed Dynamics in Freiburg (EMI), Germany was used to accelerate a spherical 2.5 mm iron meteorite projectile to 5 km s−1. A thin section of the crater subsurface was prepared and microstructures were mapped in detail [1]. Linear twin densities (i.e., the number of twins per mm) were measured using the line count method (e.g. [2]) in 39 BSE images. Additional TEM foils for twin density measurements were prepared with FIB at the GFZ Potsdam.

Results: The impact created a crater with a diameter of 56.6 ± 4.2 mm and a depth of 6.0 ± 0.4 mm. Polarized light microscopy analysis of the thin section shows that apart from intra-granular cracks and tensile fractures the main deformation features in the crater subsurface are calcite twin lamellae and open cleavage. Under crossed polarized light, some domains in calcite grains show no extinction behavior.

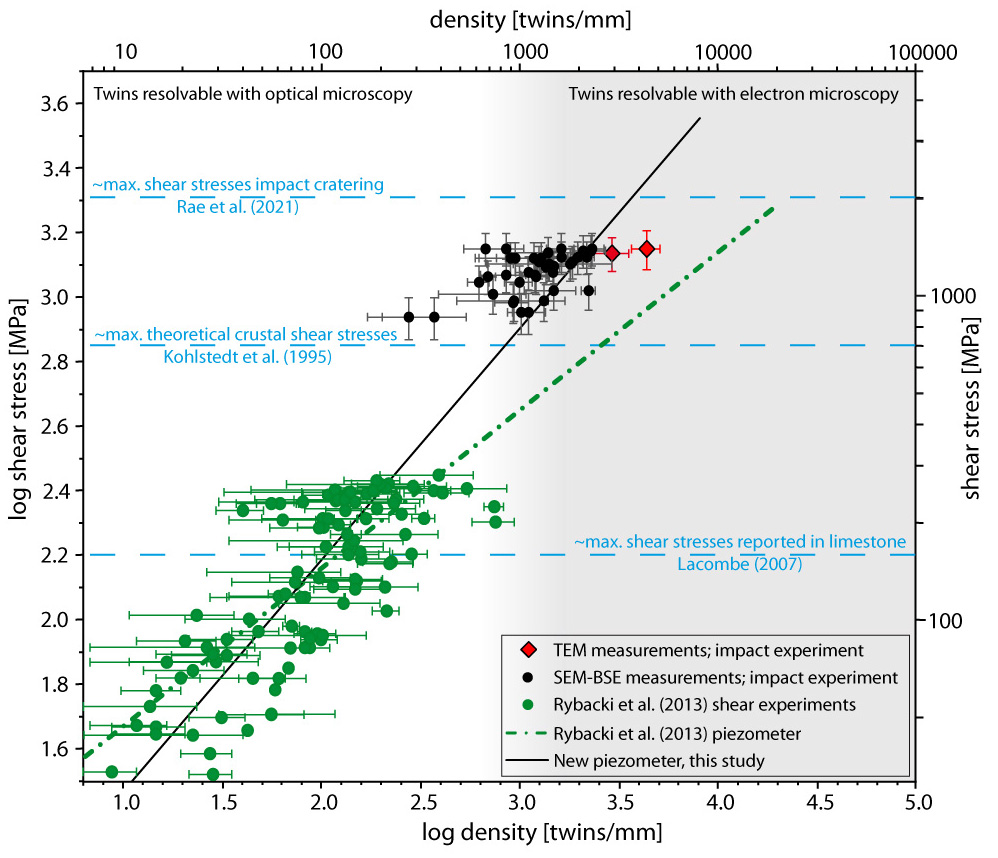

Twin densities in BSE images show local maxima of ~4000 twins/mm over short line sections of 10 µm, while averaged grain measurements near the surface can reach ~2000 twins/mm and gradually decrease with depth (Fig. 1). In the two TEM-foils a twin density of 4373 ± 711 twins/mm was measured at the crater floor, while at 350 µm below the crater floor, a twin density of 2924 ± 621 twins/mm was determined.

The cratering experiment was numerically modeled using the iSALE-2D Eulerian shock physics code in the “Chicxulub” version [3]. Calculated peak pressures exceed 4 GPa at the crater floor but rapidly decrease over several mm depth. Shear stresses of 1378 ± 130 MPa and 1333 ± 130 MPa were calculated for the two TEM samples located near the crater floor. Values determined from the BSE images range from 1378-849 MPa over ~5 mm depth in the crater subsurface.

Twin density line counting results of the TEM and BSE images are plotted against the numerically derived shear stress (Fig. 1). Experimental data from [2] are also plotted, as well as the twin density-based piezometer from [2]. The new impact data points lie above the piezometer. Combining all data points, the piezometer can be revised, giving the following equation:

log(τ)=0.738±0.057+(0.718±0.024)logNL

where τ is the shear stress and NL is the twin density.

Discussion: The systematic relationship between twin density in calcite and applied shear stress was derived for tectonic situations (e.g., [2]). The highest twin densities from [2] are less than 800 twins/mm, and the highest experimental shear stresses were less than 300 MPa. These stresses are well above the maximum shear stresses of ~140 MPa for natural limestone samples reported in [4]. In comparison, peak shear stresses from numerical models of shock waves that occur during the impact cratering process are calculated at 1-2 GPa for shock pressures between 5 and 50 GPa in crustal rocks [5].

Apart from maximum crustal shear stresses for Carrara marble at ~125 MPa, higher shear stresses in the crust are possible for other rock types. [6] calculate maximum shear stresses of ~0.7 GPa for quartzites and granites (Fig. 1). As these values are below shear stress values calculated for shock deformation in impact craters, the occurrence of twin densities >1000 twins/mm, in particular in sedimentary or other supracrustal rocks, must indicate high shear stresses characteristic for shock waves.

Figure 1: Calcite twin density from impact and shear experiments plotted against shear stress. Modified from [1].

Conclusions: We find that twin densities above 1000 twins/mm in calcite can be used as a novel indicator for high shear stresses encountered in impact cratering settings, and thus as an indicator for shock metamorphism. In polarized light microscopy, the loss of extinction and reduced interference colors in calcite in the shallow crater subsurface regions are an initial indicator for intense twinning. However, full recognition of these high twin densities requires either high resolution SEM imagery or TEM. Further experimental calibration data are certainly necessary to validate and better constrain these findings, and future studies should additionally take a detailed look at the effect of grain size on twin density (c.f. [7]).

References:

[1] Poelchau, M. H., Winkler, R., Kenkmann, T., Wirth, R., Luther, R., & Schäfer, F. (2025). Extreme twin densities in calcite—A shock indicator. Geology, 53(3), 279-283.

[2] Rybacki E., Evans, B., Janssen, C., Wirth, R., & Dresen, G. (2013) Influence of stress, temperature, and strain on calcite twins constrained by deformation experiments. Tectonophysics, 601, 20–36.

[3] Wünnemann, K., Collins, G. S., and Melosh, H. J. (2006). A strain-based porosity model for use in hydrocode simulations of impacts and implications for transient crater growth in porous targets. Icarus, 180, 514–527.

[4] Lacombe, O. (2007). Comparison of paleostress magnitudes from calcite twins with contemporary stress magnitudes and frictional sliding criteria in the continental crust: Mechanical implications. Journal of Structural Geology, 29(1), 86-99.

[5] Rae, A. S., Poelchau, M. H., & Kenkmann, T. (2021). Stress and strain during shock metamorphism. Icarus, 370, 114687.

[6] Kohlstedt, D. L., Evans, B., & Mackwell, S. J. (1995). Strength of the lithosphere: Constraints imposed by laboratory experiments. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 100(B9), 17587-17602.

[7] Rutter, E., Wallis, D., & Kosiorek, K. (2022). Application of electron backscatter diffraction to calcite-twinning paleopiezometry. Geosciences, 12(6), 222.

How to cite: Poelchau, M., Kenkmann, T., Winkler, R., Wirth, R., Luther, R., and Schäfer, F.: Extreme twin densities in calcite as a shock indicator , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-819, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-819, 2025.

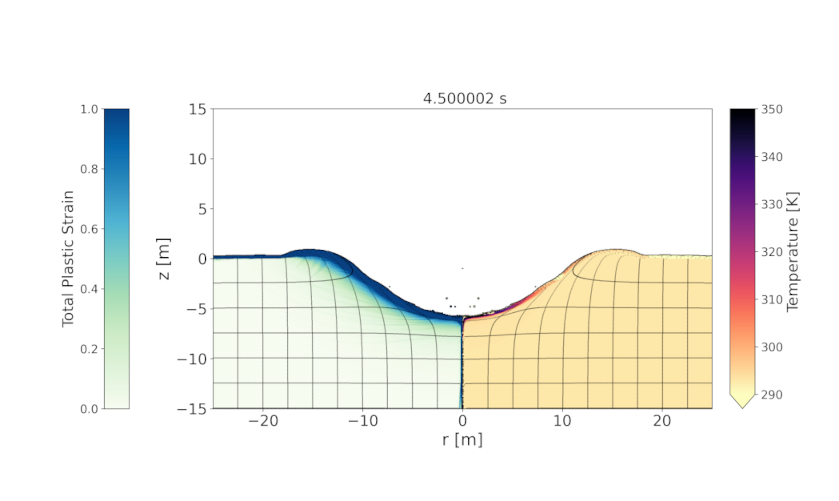

Introduction: Shock-recovery experiments are standard practice for geoscientists who desire to understand and reproduce shock features in planetary rocks [1]. When carefully designed [2,3], such experiments can induce pressures from a few GPa (impedance technique) to 70 GPa (reverberation technique). In this study, we describe the results of a shock-recovery experiment using the reverberation technique, which surpassed initial expectations by producing localized melting within a dense dunite host. The study was initially designed to investigate shock melting of troilite and its potential migration into fractures [4]. For this reason, troilite powder was placed into drilled cavities (DCs) within a dunite disk before shock loading.

Fig. 1. Setup of the cylindrical shock-recovery experiment with a) the dunite sample disk with drilled cavities (DCs), and b) the cylindrical assemblage. A tantalum foil wrapped the sample.

Methods: A dunite [5] sample disk hosted nine DCs of ~1 mm diameter and a few hundred μm in depth. Three DCs were filled with troilite (FeS [6], Fig. 1a). The sample disk was wrapped in tantalum (Ta) foil, placed into an ARMCO-iron (i.e., soft iron, >99.85% Fe) sleeve, and tightly sealed with a piston-like ARMCO-iron element (Fig. 1b). The setup was impacted by propelling a flyer plate onto an ARMCO-iron driver plate positioned ahead of the sample disk.

After shock loading, the sample was analysed at three locations: (i) the bottom surface of the sample adhering to the driver plate, (ii) the surface of the piston-like iron element, and (iii) transverse cross-sections of the disk and driver plate. Computer tomography was used to locate the DCs before preparing thin sections. Semi-quantitative chemical analyses (energy-dispersive spectrometry, EDS) were conducted to characterize the melts. The experiment was modeled with the iSALE shock physics code [7], simulating the sample with a FeS-filled DC, including Ta foil and an iron driver plate.

Fig. 2. SEM-BSE images depicting a) the heavily shocked central DC initially filled with FeS, inducing Ta, silicate, and sulfide melts, b) an initially empty DC with shock-induced Ta melts and partially melted olivine, c) an EDS map showing intrusions of Ta, silicate, and troilite melts in fractures of the dunite disk, and d) partial melts of olivine in contact with Ta melts.

Results: The sample was shock-loaded to a pressure of ~60 GPa after reverberations. The shock caused fracturing of the sample disk, inducing large tensile fractures and parallel fractures in olivine grains. Substantial crushing of olivine grains at DC locations triggered the formation of larger shock-induced cavities. The experimental pressure was sufficient to induce collapse of the DCs and partial melting of troilite within the FeS-filled DCs. However, the presence of DCs caused secondary pressure reverberations with localized melting of metallic phase components (iron, Ta foil) and silicates alongside troilite.

The resulting melts intruded into fractures, forming melt veins and melt breccia within and around the former DCs (Fig. 2). Partial melting of olivine with Ta is observed at the DCs (Fig. 2d). In the FeS-filled DC (Fig. 2a,c), the intruding melts contain FeS-rich particles embedded in a matrix of Ta- and silicate-rich melt. These FeS particles developed elongated morphologies (Fig. 2c). At initially empty DCs, Fe- and Ta-rich particles included a matrix of Ta- and silicate-rich melts (Fig. 2b). Some FeS-rich melts remained as dense clusters, exhibiting partial melting. Notably, melts at the site of initially empty DC cemented large SICs that had developed through the entire thickness of the samples beneath the DCs (Fig. 2 b). Some melts entrained unaffected olivine fragments.

Discussion and conclusions: All observations on the sample disk (melting, fracturing, deformations) generally aligned with the numerical models, except for the melting of Ta and iron (Table 1); iSALE does not simulate fracturing and melt migration. Although troilite was not the dominant contributor to melt intrusion into fractures, the resulting melt veins resemble melt breccias [8], which typically form when melts entrain grains while propagating into a less shocked environment (here, away from the DCs).

According to numerical models, these melts occurred from DCs that caused pressure concentration points (hotspots) where pressures exceeded the nominal shock pressure of ~60 GPa by at least 10 GPa. Considering that Ta appeared to shock-melt more intensively than the silicate and troilite components, the sequence of shock melting needs further explanation. Tantalum melts at 3000 K at ambient pressure or at shock pressures over 150 GPa. In contrast, troilite shock-melts at pressures >60 GPa, and dunite at >100 GPa. Therefore, the shock melting of Ta likely resulted from several compressive and tensile events, which allowed for cumulative heat buildup.

We hypothesize that Ta foil, initially bent, was first shocked by the collapsing iron driver plate and then re-shocked by the impact of its shock-heated fragments projected into the DC walls during the collapse (spalling). Additional pressure amplification occurred due to the complete closure of the DCs and the shock compression of troilite grains or dunite fragments located within them. The added thermal input likely tipped the Ta over its melting point.

In conclusion, the configuration of DCs enabled the creation of localized melting, whereas the dunite primarily experienced fracturing without melting elsewhere in the sample disk. These findings are significant for shock-recovery experiments aiming to produce melt, melt breccias, or shock veins. Strategically doping DCs with materials of interest enables targeted melting effects. Moreover, the design of metallic sample holders with embedded DCs may allow for controlled and simultaneous shock-loading of multiple materials in a single experimental run.

References:

[1] Stöffler et al. (2018) Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 53, 5–49. [2] Langenhorst and Deutsch (1994) Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 125, 407–420. [3] Langenhorst and Hornemann (2005) EMU Notes Mineral. 7, 357–387. [4] Kohout T. et al. (2014) Icarus, 228, 78–85. [5] Heikura P. et al. (2010) Geological Survey of Finland, report M06/4723/2009/68, 50 pp. [6] Moreau et al. (2021) Meteorit. Planet. Sci., 57(3), 588–602. [7] Wünnemann K. et al. (2006) Icarus, 180, 514-527. [8] Pati J. K. and Reimold W. U. (2007) J. Earth Syst. Sci., 116(2), 81–98.

How to cite: Moreau, J.-G., Stojic, A. N., Jõeleht, A., Aurich, H., Glößner, C., Virro, I., Somelar, P., Hietala, S., and Plado, J.: Shock-recovery experiment in dunite: shock features and melting hotspots from controlled imperfections., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-62, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-62, 2025.

Parallel to the study of accessory minerals as potential shock indicators, the main rock forming minerals quartz and olivine, representative of terrestrial impact cratering and planetary collisions recorded in meteorites, respectively, are still intensively used for constraining shock metamorphism. Here, we present investigations on shocked quartz from a terrestrial impact structure and shocked olivine from a chondrite meteorite, where at least two high pressure polymorphs coexist, with the aim of constraining the formation process and, thus, the shock conditions.

In the L6 ordinary chondrite Alfianello, three polymorphs with olivine composition were observed, namely olivine itself, wadsleyite, and ringwoodite. The occurrence of fine-grained aggregates of wadsleyite and ringwoodite, investigated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and 3D electron diffraction, and the presence of lamellar ringwoodite in olivine support the coexistence of different shock-induced processes in the same sample. In the case of the wadsleyite-ringwoodite aggregates, the random mutual crystallographic orientation and the complementary Fe/Mg ratio, as well as the occurrence in clasts within impact melt pockets or in the vicinity of shock veins lend support to formation by fractional crystallization from an impact melt with olivine composition during the shock pulse. On the other hand, the lamellar ringwoodite, oriented along notable crystallographic planes of olivine, suggests formation by solid-state transformation from olivine at the shock front.

The pseudotachylitic breccia from the Vredefort impact structure, one of the oldest and largest impact structures preserved on Earth, contains up to three silica polymorphs: quartz, stishovite, and coesite. In the investigated clasts in pseudotachylitic veins, quartz and coesite occur together, forming a fine-grained aggregate. The frequency of coesite occurrence, mostly limited to the center of the clasts, seems to be correlated with the position of the clast within the vein, with a maximum towards the center of the vein. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) enabled the identification of the crystallographic relationship between coesite and quartz, allowing the discrimination of the most likely formation process for coesite between crystallization from the impact melt under high-pressure conditions during the shock pulse and solid-state transformation from a likely already strongly deformed quartz or from diaplectic glass.

This work remarks the potential of modern analytical techniques to help scientists reconstructing complex deformation mechanisms, constraining the local formation conditions. These data can be used for better modelling shock metamorphic processes, improving our understanding of the global implications of planetary collisions.

How to cite: Pittarello, L., Carone, L., De Santis, V., Gemmi, M., Parlanti, P., Steiger-Thisrfeld, A., Di Michele, A., Pratesi, G., and Giuli, G.: Coexisting polymorphs in shocked rocks investigated by EBSD and TEM, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-464, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-464, 2025.

Abstract

Martian crust is enriched in iron, with olivine averaging an iron number of approximately 50. However, owing to the scarcity of terrestrial analogs with similar compositions, the shock behavior and preservation potential of Fe-rich olivine remain poorly understood. This study investigated the microstructural and spectral changes induced by shock effects in Fa50 Fe-rich olivine, providing new insights into its preservation, alteration mechanisms, and spectral evolution of Fe-rich olivine on the surfaces of Mars and Phobos.

Introduction

Iron is the second most abundant metal element in the solar system and plays a crucial role in planetary crustal evolution. Global remote sensing and in situ investigations indicate that Martian crust is enriched in iron, with olivine averaging an iron number (Fa#; Fe mola fraction of the Mg-Fe solid solution) of approximately 50. The silicates detected on Martian moons and some asteroids [1] potentially originated from Martian impact ejecta [2,3], suggesting that the primordial materials of Phobos and Deimos may contain iron-rich olivine given its abundance in the Martian crust [4]. However, due to the scarcity of terrestrial analogs with similar compositions, the shock behavior and preservation potential of Fe-rich olivine remain poorly understood, limiting our ability to assess how impacts modify its mineralogy and spectral properties on Mars and Phobos.

Methods

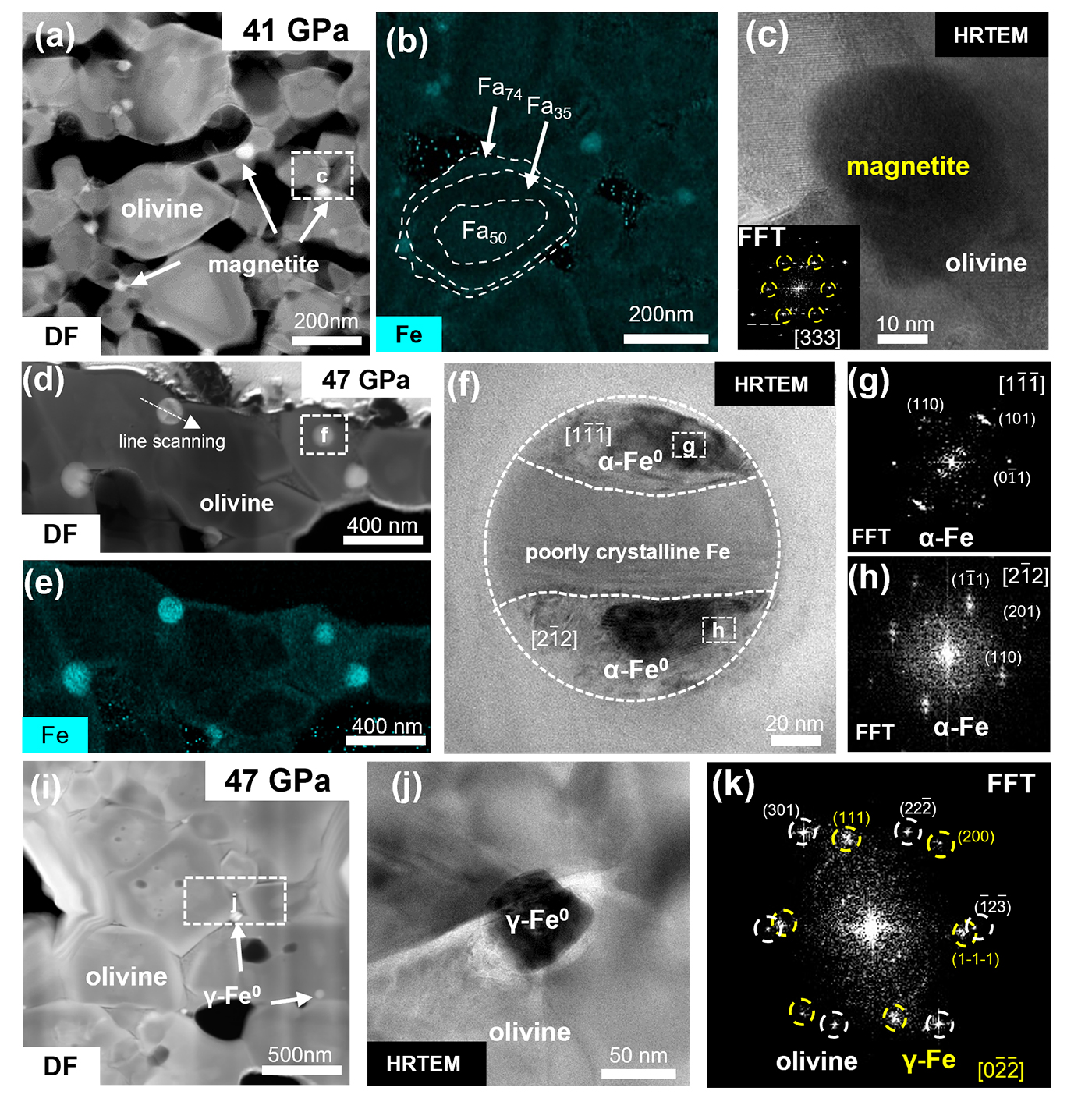

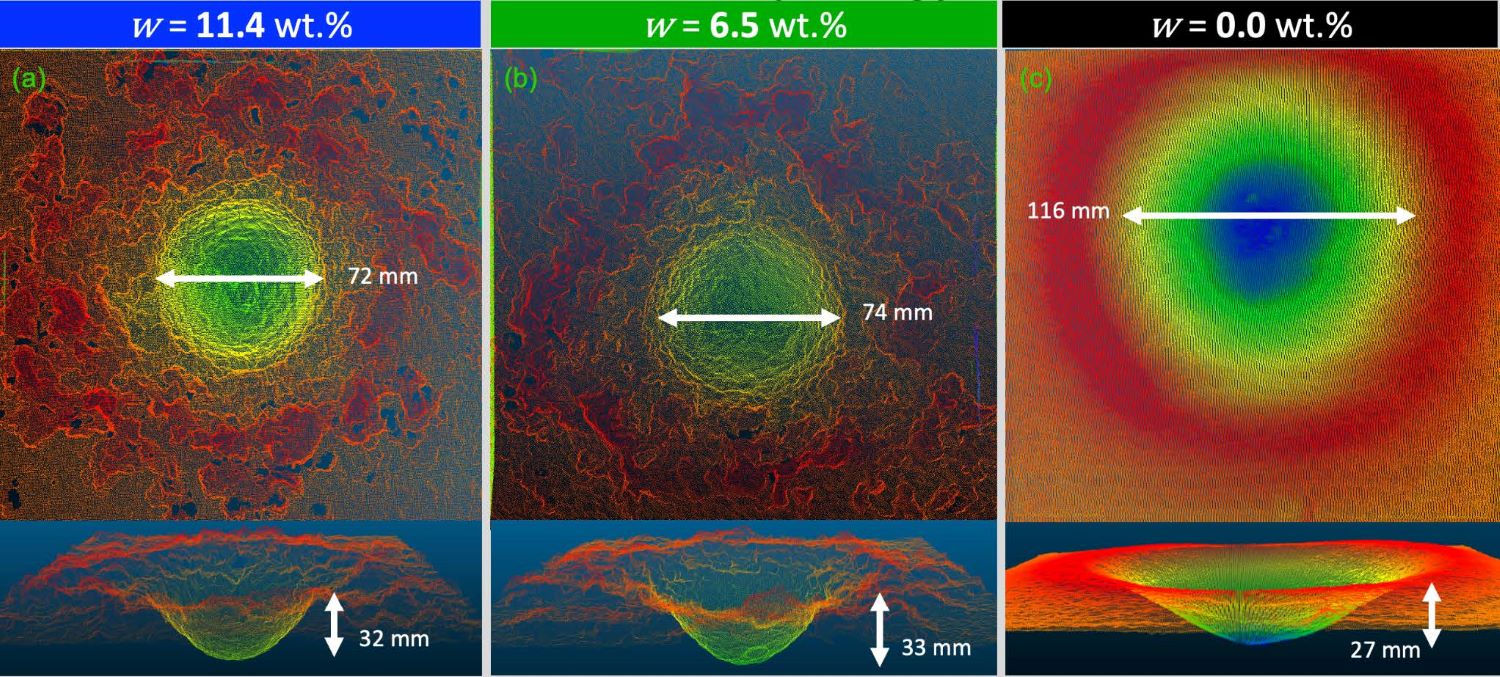

Shock recovery experiments were conducted on synthetic Fa50 olivine using one- and two-stage light gas guns at shock pressures of 18 GPa, 31 GPa, 41 GPa, and 47 GPa, corresponding to impact velocities between 0.89 and 1.95 km/s. Post-shock samples were analyzed using Raman, visible-near-infrared (VNIR), and mid-infrared (MIR) spectroscopy to assess spectral modifications. Microstructural and compositional features were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), focused ion beam (FIB) sectioning, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Results

The shocked olivine samples exhibited systematic microstructural and spectral changes that varied with increasing shock pressure (Fig. 1). Shocked Fa50 olivine demonstrated shock-induced Fe migration and zoning at pressures ≥31 GPa, with the development of a three-layer Fe distribution pattern (core-intermediate-rim) accompanied by nanoscale α-phase (~120 nm) and γ-phase (20-50 nm) metallic iron particles. At shock pressures ≥41 GPa (corresponding to estimated transient temperatures ≥1185 K), minor magnetite particles (20–50 nm) were observed at olivine grain boundaries. Nanoscale vesicles, often associated with dislocations and grain boundaries, were also observed, indicating localized gas release. These phenomena indicate that magnetite can form not only through the direct decomposition of olivine but also via the oxidation of nanoscale metallic iron particles by oxygen vesicles generated during the impact process. Despite these extensive shock effects, no high-pressure olivine phases were detected, likely due to the short duration of the shock events.

There is a correlation between shock products and their spectral properties. Fa₅₀ olivine exhibited a reduced grain size, increased surface roughness, decreased crystallinity, and lower overall Fe content after impact. These structural changes resulted in 1) progressive peak shifts, increasing peak separation, and broadening of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) in the Raman spectra, indicating increasing structural disorder; 2) pressure-dependent trends, with increasing reflectance and spectral bluing at lower pressures (18 GPa), followed by reduced reflectance, redshifted absorption bands, and weakened absorption features at higher pressures (31-47 GPa) in the VNIR spectra. 3) Characteristic shifts in the Christiansen feature (CF) and Reststrahlen bands (RB1 and RB4) in the MIR spectra, particularly at pressures ≥31 GPa.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that impacts on Fe-rich silicates provide an alternative mechanism, independent of water-rock interactions, to influence the redox evolution of the Martian surface and the composition of its early atmosphere. Impact-induced nanoscale metallic iron, magnetite particles, and nanovesicles may directly contribute to the spectral reddening and localized bluing observed on the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos. However, longer cooling durations, more extensive Fe migration, and the formation of larger particles are more likely under natural conditions than under laboratory settings, highlighting the need for further experimental and observational studies focused on Martian moons.

Acknowledgements:This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42441803, 42373042, 42422201, and 42003054). Youjun Zhang is supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2023NSFSC1910).

Figure 1: TEM images of metallic iron and magnetite particles. (a) and (b) Dark-field (DF) TEM image and iron elemental mapping of olivine shocked at 41 GPa. The Fe distribution within olivine exhibits a three-layer zoning pattern with average Fa# values of 50, 35, and 74 from the core to the rim. (c) High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of an iron-rich particle region in the sample shocked at 41 GPa. (d) DF image of olivine shocked at 47 GPa. (e) Fe elemental mapping of olivine shocked at 47 GPa, revealing that the nanoscale particles are iron rich. (f) HRTEM image of an iron particle with a diameter reaching 100 nm. The particles exhibit distinct contrast variations, divided into upper, middle, and lower regions, which are identified as α-Fe through fast Fourier transform (FFT) calibration. (g) and (h) FFT patterns of the upper and lower regions of the iron particle. (i) DF-TEM image of olivine shocked at 47 GPa. The nanoscale metallic iron particles are dispersed at the corners and edges of the grains and within the interior. (j) HRTEM image of an iron particle region in the sample shocked at 47 GPa. (k) FFT pattern of the iron particle shown in (c), confirming its identification as γ-phase metallic iron.

References

[1] Bibring, J., Ksanfomality, L., Langevin, I., et al., 1992, Adv. Space Res., 12(9): 13.

[2] Bagheri, A., Khan, A., Efroimsky, M., Kruglyakov, M., & Giardini, D., 2021, Nat. Astron., 5(6): 539.

[3] Canup, R., & Salmon, J., 2018, Sci. Adv., 4(4): eaar6887.

[4] Koeppen, W.C., & Hamilton, V.E., 2008, J. Geophy. Res.: Planets, 113(E5).

How to cite: Tai, K., Zhao, Y.-Y. S., Zhang, Y., Song, W., Yang, Y., Zhang, M., Qi, C., Du, W., Cao, F., Pang, R., Lin, H., Yin, Z., and Liu, Y.: Shock effects of Fa50 iron-rich olivine: Spectral and microstructural implications for Mars and Phobos, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-556, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-556, 2025.

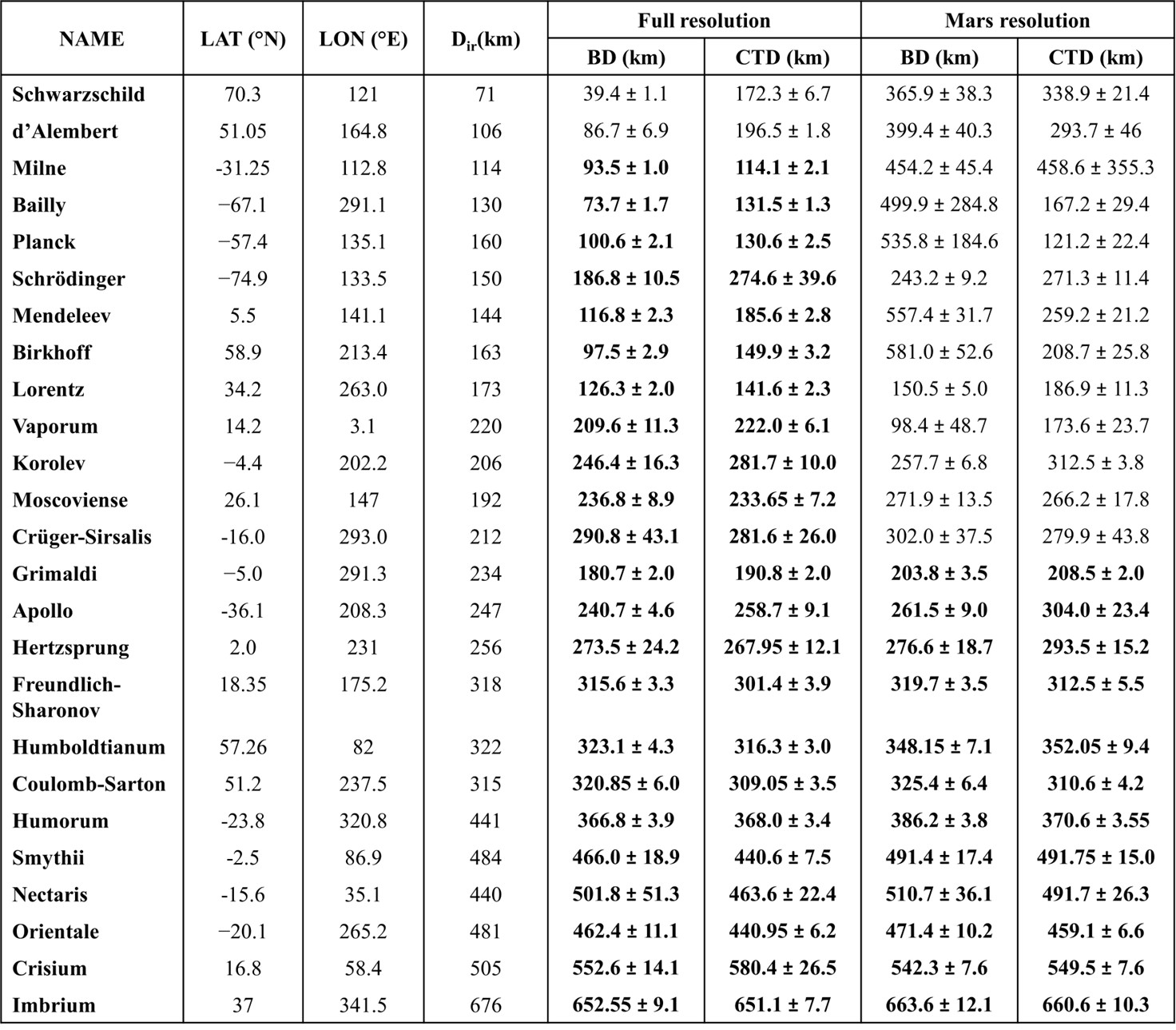

Impact cratering is one of the most important geological processes that has affected the evolution of the Moon’s crust. Impact cratering fractures the crust and generates porosity, which in turn affects physical properties such as the bulk density, thermal conductivity, and seismic velocity. As a result of NASA’s GRAIL mission, the lunar gravity field has been resolved to an unprecedented spatial resolution of up to 3 km in places, making it possible to estimate not only how the density of the upper crust varies laterally (e.g., Wieczorek et al. 2013, Wahl et al. 2020), but also how density varies with depth (e.g., Besserer et al. 2014, Gong et al. 2016, Šprlák et al. 2020). Estimating the 3D density structure of the crust is a non-unique problem, and in order to make this problem tractable, previous studies needed to impose the form of the density profile, which was assumed to be either constant, linear, exponential, or layered.

In the pioneering work of Besserer et al. (2014), a localized spectral admittance approach (Wieczorek & Simons, 2005; 2007) was used to derive the so-called effective density spectrum, and this was compared to predictions from models with a prescribed density profile. This study made use of an early gravity model GRGM900B that had a maximum spherical harmonic degree of 900 (Lemoine et al., 2014), which was the state of the art at the time. However, their analysis only made use of degrees up to 550, which was their estimate of the global resolution of the model. This study tested two simple parameterizations of the density profile, linear and exponential, but these are in all likelihood an over simplification of reality. Though this study provided many valuable insights, there are still many questions concerning how sensitive the Moon’s gravity is to depth variations in density.

Over the past decade, several advances have made a reanalysis of the Besserer et al. (2014) results pertinent. First, new gravity models have been constructed that utilize all data from the GRAIL extended mission phase, with the most recent being developed up to degree 1800 (GL1800F, Park et al., 2025). Šprlák et al. (2018) have shown that the degree 550 cutoff used by Besserer et al. (2014) is problematic, given that it was based on an estimate of the gravity field below the Brillouin sphere (the maximum radius of the planet). Furthermore, Besserer et al. (2014) used the same maximum spherical harmonic degree for all of their localized analyses, but the spatial resolution of the gravity model is known to be better at the poles where the spacecraft orbits overlap and in places where the spacecraft altitude was lower than average.

In this study, we improve upon previous work by applying localized spectral analyses combined with a Bayesian inversion method. In comparison to Besserer et al., we use a smaller spherical cap size of 9° with a smaller spectral bandwidth of 87. By using all localization windows with concentration factors greater than 0.99, we have 23 windows in comparison to 30 used by Besserer et al. We make use of the gravity model GL1800F, which has a resolution that is twice greater than the previously employed GRGM900B model. Furthermore, we better quantify the maximum permissible degree of our localized analyses by use of a degree-strength map and by use of the correlation between gravity and topography. Lastly, we use a multi-layer depth-dependent density model where the density and depth of each layer are sampled using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method.

We focus our analysis on the lunar pole regions, where dense orbital coverage by the GRAIL mission provides particularly high-resolution gravity data. In particular, based on the correlation between gravity and topography, we estimate that the spatial resolution of these regions is close to spherical harmonic degree of 900, which is comparable to what is given by the degree strength map of GRGM1200 RM1. For the polar regions, we test density models that are constrained to increase with depth, as well as models that have no constraints. We also investigate models with different numbers of layers. From our numerical inversions, we expect to be able to determine the form of the density profile with depth in the crust, and also to determine the maximum depth that is sensitive to the GRAIL data.

Reference:

Besserer, J., Nimmo, F., Wieczorek, M. A., et al. (2014). GRAIL gravity constraints on the vertical and lateral density structure of the lunar crust. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(16), 5771–5777.

Gong, S., Wieczorek, M. A., Nimmo, F., et al. (2016). Thicknesses of mare basalts on the Moon from gravity and topography. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 121(5), 854–870.

Lemoine, F. G., Goossens, S., Sabaka, T. J., et al. (2014). GRGM900C: A degree 900 lunar gravity model from GRAIL primary and extended mission data. Geophysical Research Letters, 41(10), 3382–3389.

Park, R. S., Berne, A., Konopliv, A. S., et al. (2025). Thermal asymmetry in the Moon's mantle inferred from monthly tidal response. Nature. (in press)

Šprlák, M., Han, S.-C., & Featherstone, W. E. (2018). Forward modelling of global gravity fields with 3D density structures and an application to the high-resolution (~ 2 km) gravity fields of the Moon. Journal of Geodesy, 92(8), 847–862.

Šprlák, M., Han, S.-C., & Featherstone, W. E. (2020). Crustal density and global gravitational field estimation of the Moon from GRAIL and LOLA satellite data. Planetary and Space Science, 192, 105032.

Wahl, D., Wieczorek, M. A., Wünnemann, K., et al. (2020). Crustal Porosity of Lunar Impact Basins. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 125(4), e2019JE006335.

Wieczorek, M. A., & Simons, F. J. (2005). Localized spectral analysis on the sphere. Geophysical Journal International, 162(3), 655–675.

Wieczorek, M. A., & Simons, F. J. (2007). Minimum-variance multitaper spectral estimation on the sphere. Journal of Fourier Analysis and Applications, 13(6), 665–692.

Wieczorek, M. A., Neumann, G. A., Nimmo, F., et al. (2013). The Crust of the Moon as Seen by GRAIL. Science, 339(6120), 671–675.

How to cite: Yang, J. and Wieczorek, M.: Porosity beneath the lunar polar regions as revealed by GRAIL gravity data., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-781, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-781, 2025.

Introduction:

The lunar south polar region has a complex evolutionary history encompassing multiple impacts as well as the trapping of water ice and other volatiles. The stratigraphic sequence of impact and basin ejecta, volcanic deposits, volatiles, and other more-local process such as mass wasting is poorly understood in many areas of the poles. Age dating of large craters [1,2] and areas of light plains [3] demonstrates the complex sequence of impact basin and crater overprinting. In particular, [3] demonstrate that the smooth “light plains” units across the south pole have clusters of ages indicating deposition associated with Schrödinger and Orientale basins, Shackleton crater, and some local events.

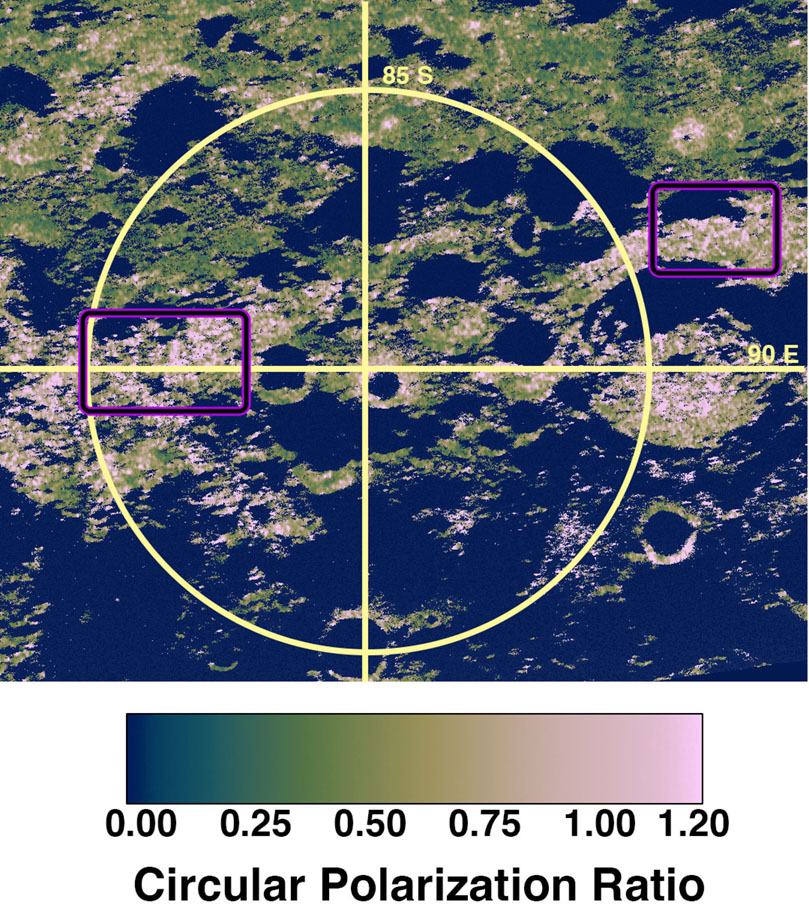

Radar data can be used to help understand the surface and subsurface structure of the regolith. S-band radar waves penetrate about a meter, and P-band radar can reach several meters depth in lunar materials. Prior radar observations of the lunar south polar region revealed relatively radar-bright areas with high circular polarization ratio values (CPR) [4,5]. CPR is the ratio of the same sense polarized wave that was transmitted over the opposite sense polarized wave and is often used as a measure of roughness. Areas mapped as light plains have high CPR values and were interpreted as fluidized ejecta from basin impacts [4]. Some young impact craters also have very high CPR values, which could possibly be due to excavated rocks from a basin ejecta melt layer under the surface [5].

In this work we focus on tens-of-kilometer diameter craters and areas of light plains. These regions have moderate to high CPR values in P-band radar data that imply a component of scattering from abundant rocks that could be in the surface or subsurface (Figure 1). Understanding the regolith layering and the surface rock abundance will help us better determine their origin and relative sequence, especially in the areas of light plains where age dating is challenging due to equilibrium conditions [3].

Figure 1: Arecibo Observatory P-band image of the lunar south pole. The image is colorized CPR overlaid on a total power image. The purple outlined boxes show the locations of the smooth plains investigated in this study.

Comparing optical images and radar datasets:

Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter ShadowCam observations provide an opportunity to investigate the morphology and reflectance of areas that are permanently or intermittently in shadow [6] and to map features across both sunlit and shadowed areas. We use ShadowCam images with multiple lighting geometries to map surface rocks, surface textures, and evidence of mass wasting. In areas of smooth plains, the lighting geometry can be particularly difficult due to their complex topography and relatively low elevation. We use mosaics of some of these areas to better track features over larger areas.

Radar observations are available from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Mini-RF instrument (12.6 cm wavelength, S-band), and Arecibo Observatory (12.6 cm wavelength, S-band, and 70 cm wavelength, P-band) with different viewing geometries. The wavelength of the radar data affects the scattering behavior – longer wavelengths will penetrate deeper and are less sensitive to smaller cm-sized rocks. CPR images are available for all three datasets.

Results and Discussion:

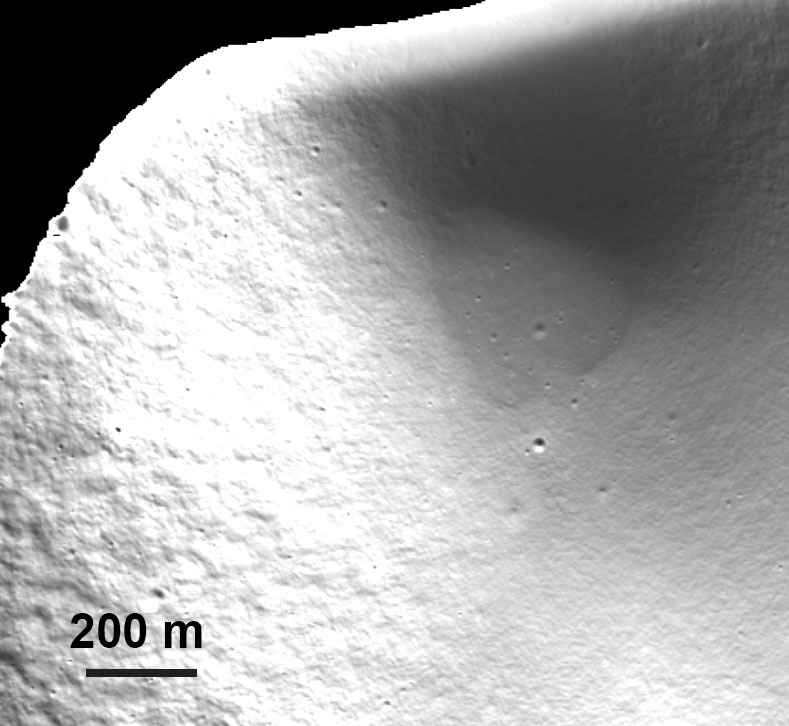

The areas of mapped light plains with high CPR values have very different surfaces from similar high-CPR valued fresh impact craters. The fresh impact craters have extremely rugged ejecta blankets and interiors as shown in ShadowCam images. The slopes and interiors of Wapowski and Hale Q craters have landslides and extended areas of surface rocks (Figure 2). The rocks have sizes ranging from near the detection limit of the ShadowCam images (~2 m) to ~ 30 m in diameter. They are found on top of hummocky surfaces in the crater interior, exposed in crater walls, and exposed in patches or layers within larger hummocks. There are also extensive lineations on the floor hummocks, possibly from mass wasting and slumping of regolith. The rocks and surface textures create a very rough surface from the centimeter to decimeter scale, likely explaining the high CPR values measured at both S-band and P-band.

Figure 2: ShadowCam image of the interior of Hale Q crater showing abundant large surface rocks and lineated surface texture (especially lower left). Image M022457496S.

In contrast, light plains regions north of de Gerlache (-85.9°, 270° E) and northeast of Amundsen crater (-83.4°, 65.7° E) have many small (meters to tens-of meter diameter) impact craters but very few visible surface rocks. These relationships suggests that the high CPR values are produced by a buried rough surface, buried rocks, or surface rocks below the ShadowCam detection limit. The abundance of small impact craters in these light plains areas suggests that they are comprised of a rock layer or layers that are different from the nearby highlands. This layer could be the result of basin ejecta or ejecta deposits from nearby craters [3], which could have been deposited as a molten or partially molten deposit. Interestingly, some small craters south of Drygalski have ponded material in their floors (Figure 3), similar to melt ponds previously identified by [7]. Lunar impact melts have previously been found to have very high CPR values, probably due to the surface structure of the cooled melt [8,9]. Current work involves mapping changes in surface texture across the light plains regions, including mapping of possible impact melt deposits.

Figure 3: ShadowCam image showing a flat floor in a topographic depression that could be ponded impact melt. Image M047084443S.

References:

[1] Tye et al. (2015), Icarus, 255, 70-77, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2015.03.016.

[2] Deutsch et al. (2020), Icarus, 336, 113455, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113455

[3] Giuri, B. et al (2024). JGR, 129, e2024JE008605, doi: https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JE008605.

[4]Campbell B. A. and Campbell D. B. (2006), Icarus, 180, 1-7, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2005.08.018.

[5] Campbell B. A. et al. (2018), Icarus, 314, 294-298, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2018.05.025.

[6] Robinson M. S. et al. (2023), JASS, 40(4), 149-171, doi: 10.5140/JASS.2023.40.4.149.

[7] Robinson, M. S. et al. (2016), Icarus, 273, 121-134, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2015.06.028.

[8] Carter et al. (2012), JGR, 117, E00H09, doi:10.1029/2011JE003911.

[9] Neish, C. D. et al. (2021), Icarus, 361, 114392, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114392.

How to cite: Carter, L., Grieser, S., Robinson, M., Mahanti, P., Denevi, B., and Kinczyk, M.: Mapping the surface and subsurface structure of rugged impact crater and basin ejecta near the lunar south pole, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1197, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1197, 2025.

Introduction:

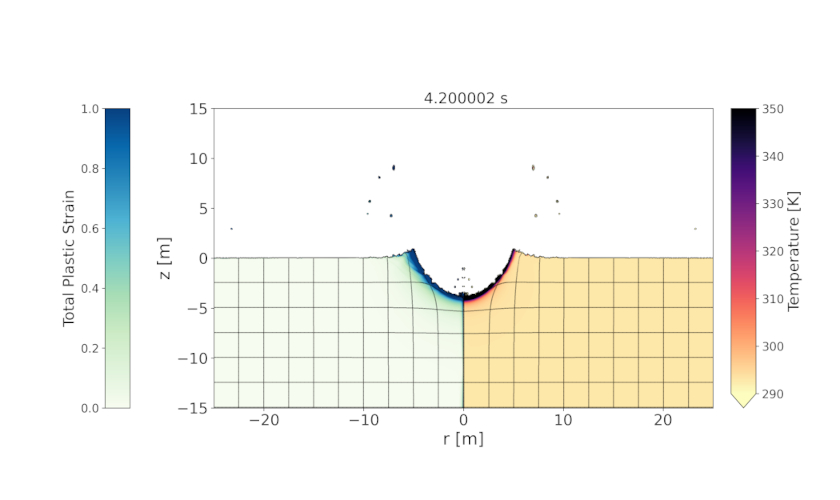

Numerical impact simulations and laboratory experiments often only focus on vertical impacts in homogeneously layered targets. Most impacts, however, occur at an oblique angle (< 90° to the horizontal), with the most likely angle being 45° [1]. Planetary surfaces either have active land-forming processes or are heavily cratered, both of which introduce further complexity to impact processes in the form of pre-existing topography and variations in sub-surface structure. Previous studies have shown that both impact angle [e.g., 2] and target heterogeneities [e.g., 3] play a significant role in crater formation, causing asymmetries in the final crater morphology, central uplift and ejecta distribution. We are conducting a systematic 3D numerical study to investigate the complex interplay of pre-existing topography, changes in crustal thickness, and impact angle and azimuth. To constrain the parameter space and demonstrate potential applications of this investigation, we present a case study on the Schrödinger basin impact event. The ~320 km lunar peak ring basin shows several asymmetries that have been attributed to both target heterogeneity [4, 5] and an oblique impact [6].

Methods:

We use the iSALE3D shock physics code [7, 8] to numerically model crater formation in a variety of heterogeneous targets and for a range of impact azimuths and angles.

For the Schrödinger basin, we assume a pre-impact terrain dominated by the influences of SPA with an eastward sloping topography and crustal thinning from 40 to 20 km. We choose target and impactor parameters based on successful 2D simulations [5]. Granite and dunite, which are the best available material analogues, were used to describe the crust and mantle. For computational expediency the impactor is represented by the same material model as the crust, implying an impactor density of 2650 kg/m3. We use a 25 km-diameter impactor and collisional speed is increased for oblique angles to preserve a vertical velocity component of 15 km/s. To produce a crater in the centre of the layered setup, the point of impact is offset by 40 and 50 km in the 45°- and 30°-degree scenarios, respectively. We use the “block model” for acoustic fluidization to facilitate late-stage collapse [9]. The Schrödinger simulations have a resolution of 1250 m (10 cells per projectile radius). We compare our results to LOLA topography [10] and GRAIL crustal thickness data [11].

Schrödinger Case Study - Results and Discussion:

Sloping Topography and Changes in Crustal Thickness.

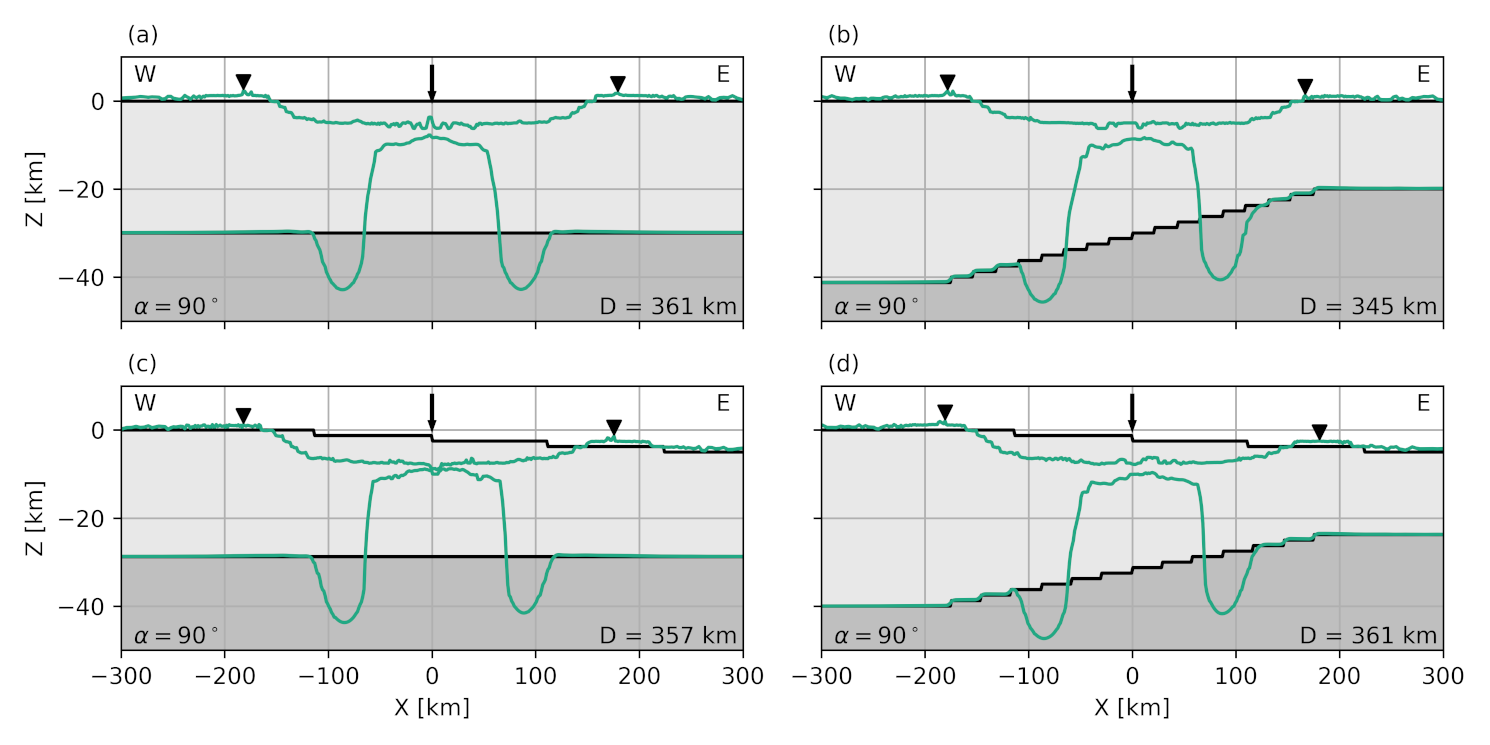

Figure 1. Vertical impact into (a) horizontal layers, (b) flat surface topography and thinning crust, (c) sloping surface topography and flat crust-mantle interface, and (d) sloping surface topography and thinning crust. Simulation results, overlying the pre-impact crust (light grey) and mantle (grey).

Sloping topography and changes in crustal thickness below the pre-impact surface cause asymmetry in the shape of the final crater and central uplift (Fig. 1). Simulations that include the eastward sloping topography produce higher and steeper crater walls in the west, consistent with observed LOLA topography. While absolute basin depths are greater for these simulations (~ 6km), relative depths (i.e. the difference between the post- and pre-impact surface) stay largely consistent across all simulations (4.25 to 4.5 km) and align with the observed average depth of the Schrödinger basin (4.5 km) [4]. Final basin diameter, which scales with the mass and velocity of the impactor [12], is independent of the pre-impact layer setup.

Impact Angle and Azimuth.

Figure 2. Oblique impacts (45° and 30°) into a homogeneously layered target (left), and into a heterogeneous target with an east to west (middle) and west to east (right) impact azimuth.

Oblique impacts in a flat, constant crustal thickness target produce asymmetry both in the final surface topography and in the central uplift with a wider and deeper annular bulge in the uprange direction (Fig. 2). In a heterogeneous target, there is an interplay between impact azimuth and target effects. The effect of crustal thinning seems to be offset by the effect of oblique impact in the east to west impact scenario, while the impact trajectory enhances asymmetries introduced by target heterogeneity in the west to east impact. Overall, final craters are larger than in a vertical impact, suggesting that the scaling of crater dimensions might be more complex than assumed.

Based on our results, the almost absent crater rim in the south and the higher and steeper crater walls in the west observed in LOLA topography, could support the scenario of an oblique impact from south-east to north-west [6]. A more comprehensive analysis of crustal thickness below the basin will provide more insights into the crater’s formation.

Conclusions:

The Schrödinger case study shows that even subtle variations in target heterogeneity and impact trajectory can produce asymmetries in final crater structure. Modelling impact craters of scientific interest in a more realistic context will lead to a better understanding of the pre- and post-impact distribution of materials and crater formation processes.

Our ongoing 3D numerical study will explore a wide range of impact scenarios to systematically investigate and disentangle the complex interplay of target heterogeneity and impact trajectory.

Acknowledgments: We gratefully acknowledge the developers of iSALE. We thank Caroline Chalumeau whose MSci project provided the inspiration for the work presented here.

References:

[1] Shoemaker, E. M. (1961). Phys. and Astron. of the Moon, 283–359. [2] Davison, T. M., & Collins, G. S. (2022). Geophys. Res. Letters, 49(21), e2022GL101117. [3] Aschauer, J., & Kenkmann, T. (2017). Icarus, 290, 89–95. [4] Kramer G. Y. et al. (2013) Icarus, 223(1), 131–148. [5] Kring D. A. et al. (2016) Nature Comm., 7(1), 13161. [6] Kring, D. A. et al. (2025) Nature Comm., 16(1), 1–7. [7] Elbeshausen D. et al. (2009) Icarus, 204(2), 716–731. [8] Elbeshausen D. and Wünnemann K. (2011) Proc. 11th Hypervel. Impact Symp., Vol. 4, 287-301. [9] Wünnemann K. and Ivanov B. A. (2003). Planet. Space Sci., 51, 831–845. [10] Smith D. et al. (2010). Geophys. Res. Letters, 37(18). [11] Wieczorek M. A. et al. (2013) Science, 339(6120), 671–675. [12] Holsapple, K. A. (1993). Rev. of Earth and Planet. Sci., Vol. 21, 333–373.

How to cite: Kallenborn, D. P., Collins, G. S., Davison, T. M., Kring, D. A., and Wieczorek, M. A.: Three-Dimensional Numerical Impact Simulations of Crater Formation in Heterogeneous Targets, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1373, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1373, 2025.

Introduction

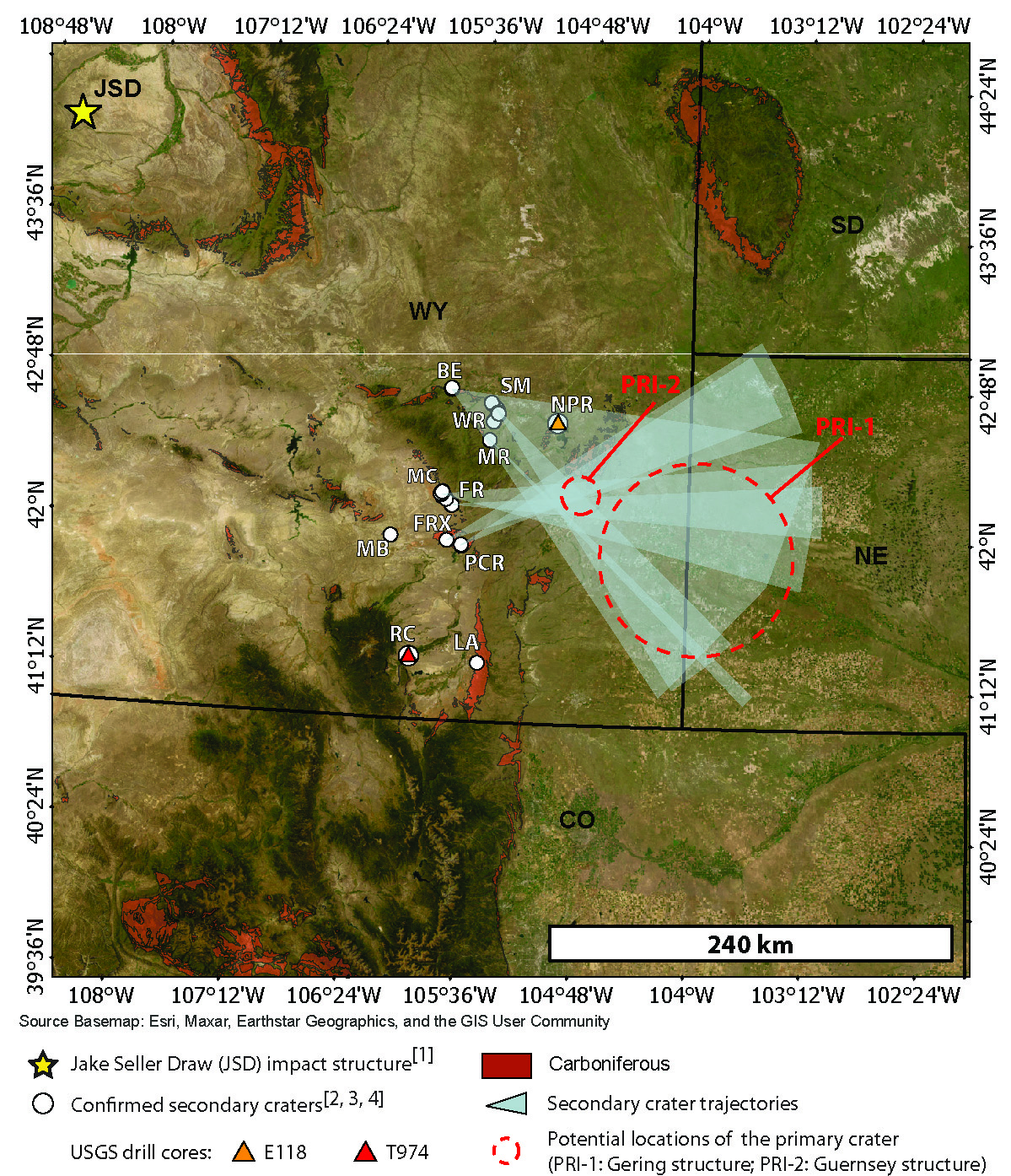

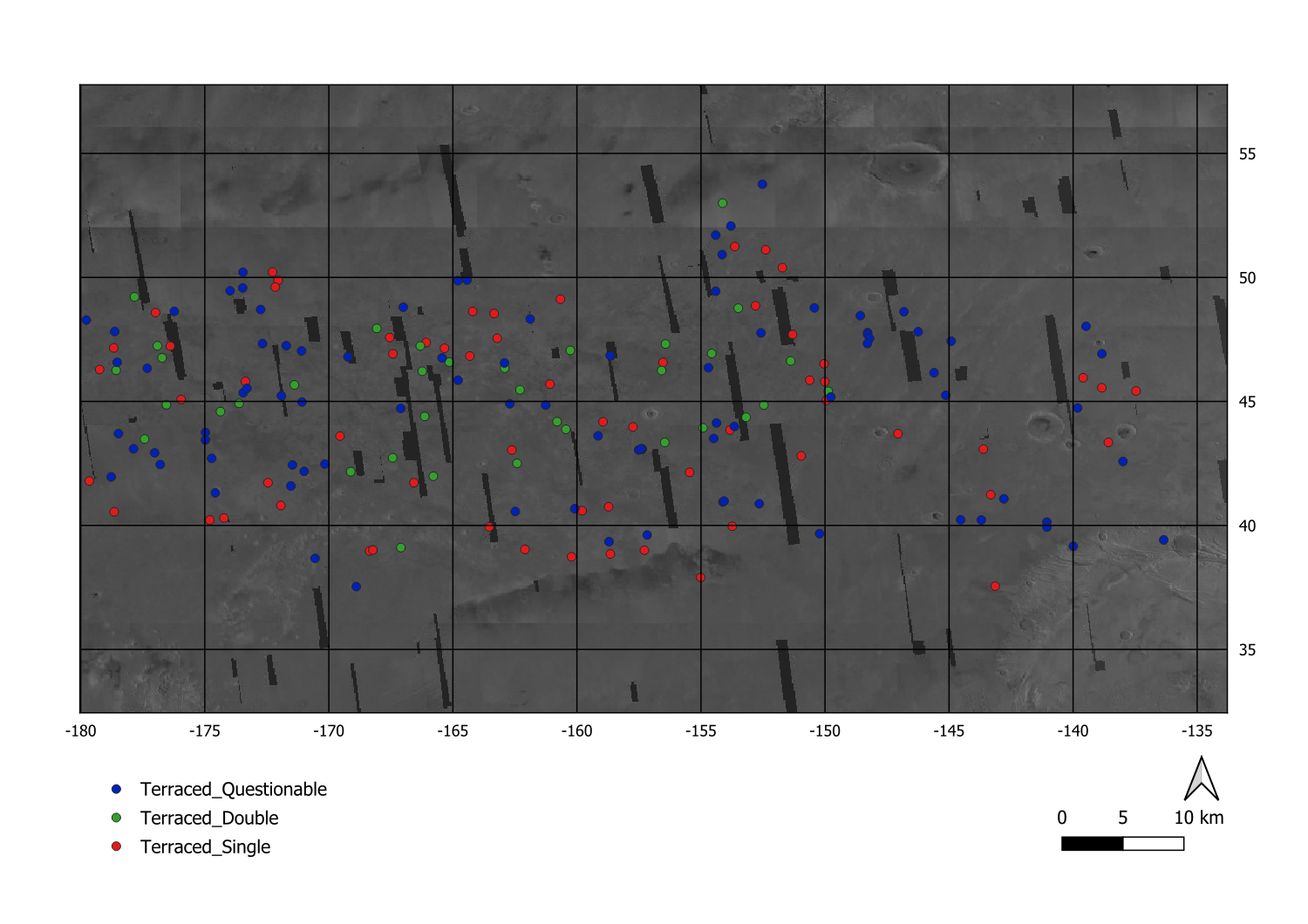

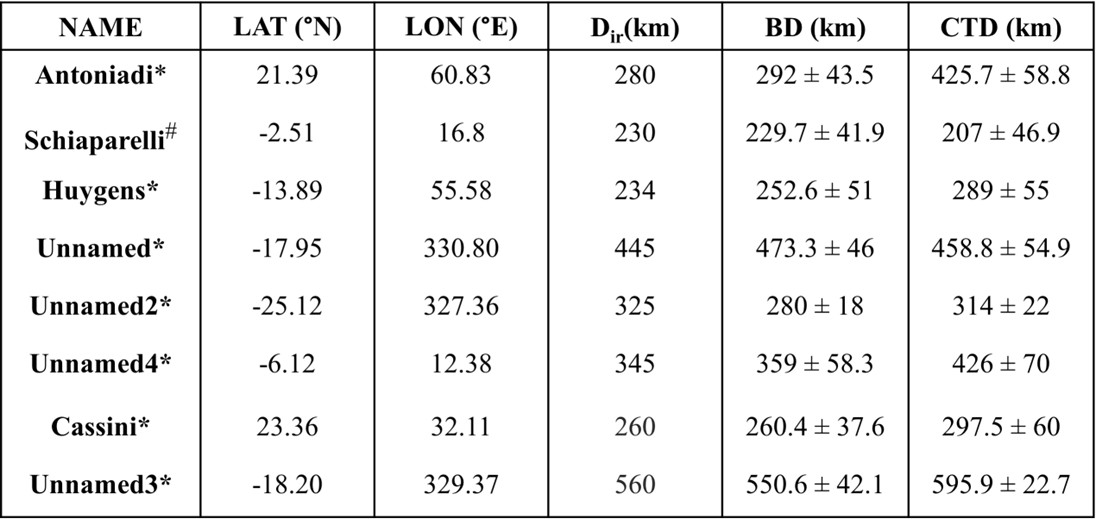

Crater morphology is widely used to constrain target properties [1]. New investigations reveal ejecta spatial distributions as yet another promising subsurface probe [2,3]. In contrast to natural impacts, hypervelocity impacts of mission hardware allow us to eliminate uncertainty on impact conditions (projectile type, velocity, impact angle) and use impact sites to put tighter constraints on target properties.

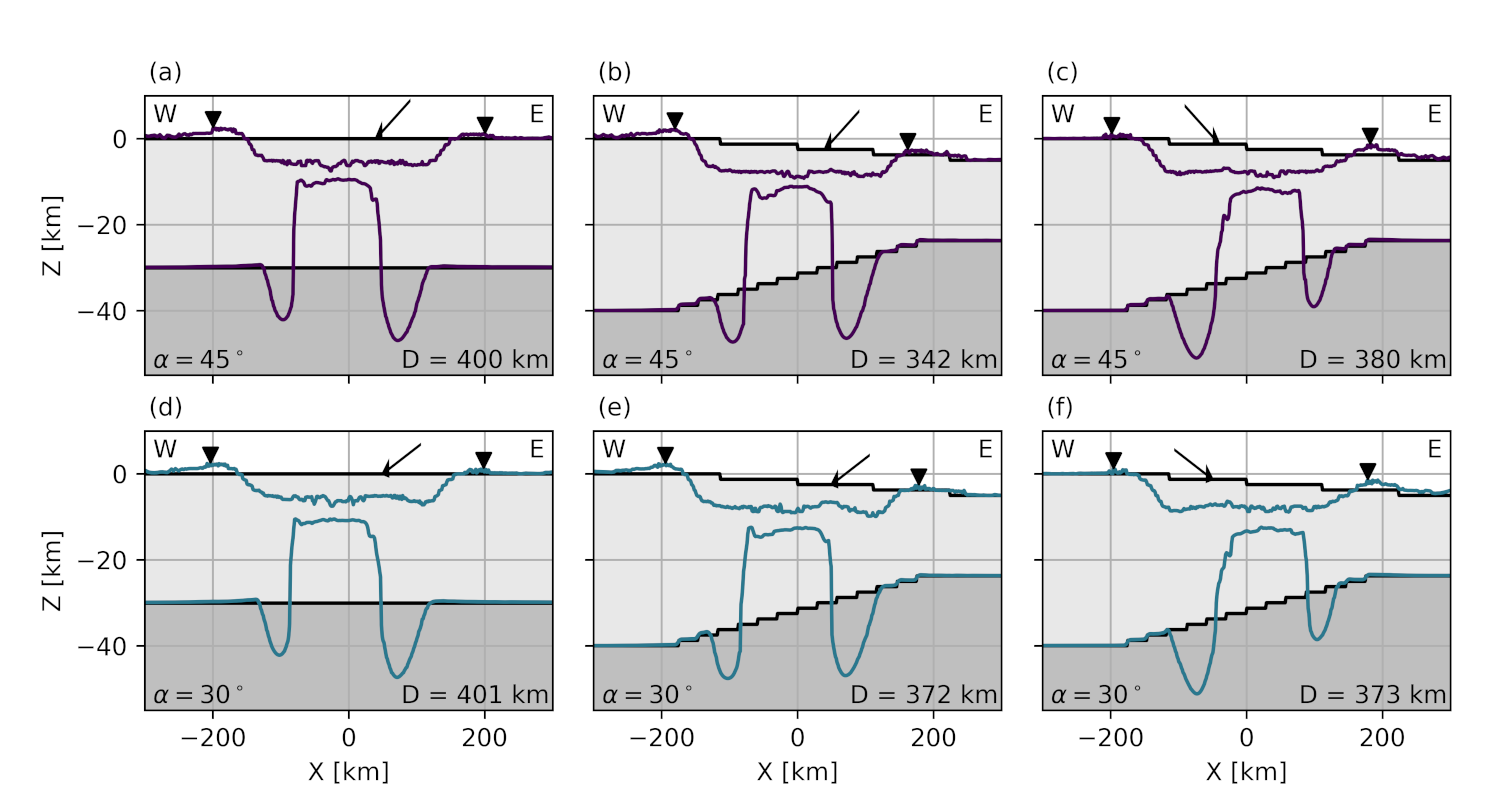

During Mars 2020 entry, the cruise stage was detached from the entry vehicle (EV) carrying the Perseverance rover. Soon after, the EV ejected two cruise ballast mass devices (CBMD), 77 kg each, made of tungsten and unlikely to have broken up during entry [4]. The cruise stage must have fragmented into at least 3 pieces of uncertain characteristics because in total 5 new co-located craters were identified (this abstract), leading to uncertainty on which craters resulted from CBMDs. Here, we a) identify CBMD craters, and b) use them to investigate target properties of the area roughly 70 km to the north-west from Jezero crater.

Methods

The Program to Optimize Simulated Trajectories II (POST2), which is the flight dynamics tool used by the Mars 2020 team, predicted the fate of various pieces of hardware, including CBMDs [5]. We use their pre-flight landing ellipses, and find coordinates of 5 craters after precisely georeferencing image data [see 6]. We obtain their locations as follows: we 1) use HRSC products orthorectified to MOLA (a base), 2) register CTX images to that base, 3) register a HiRISE image to CTX. A pre-impact HiRISE image exists only for CMBD-a, -c and -e (Fig. 1), hence we measure ejecta radii only for those craters, and build up on the procedure from [7]: 1) we georeference pre- and post-impact HiRISE images, 2) subtract them, 3) map the residual, 4) sample the edge of the polygon with equidistant points, 5) measure distances between these points and crater centers (Fig. 2). Impact sites are analyzed in QGIS. In order to estimate target properties, we use scaling relations from [8].

Preliminary results

Location. Figure 1 displays the locations of 5 craters (marked as CBMDa-e). The outcome of the pre-flight simulations of trajectories for two cruise ballast mass devices, CBMD1 and CBMD2, are also shown as 99 percentile landing ellipses. In order to compare these two results, we calculated distances between a) all craters, b) craters and ellipse centers, c) shortest distances to the ellipses. These are reported in Table 1.

Crater CBMD-e falls within the landing ellipse of both CMBD2 and CMBD1 (but is closest to the center of CBMD2). The shortest distances to the center of the ellipse of CBMD1 are for craters CMBD-b, -a and -c, respectively, but only CBMD-c is located within 100 m from the landing ellipses. If we assume that CBMD-e is one of the craters formed by either of the ballast masses, we can use its distances to other craters as another constraint. For example, both CBMD-a and -c match the distance between the two centers of the ellipses (1141 m) to within the approximate width of each ellipse. Putting these arguments together (gray cell highlights in Table 1), we conclude that craters CBMD-c and CBMD-e are the most likely matches for the impacts of the original cruise ballast masses of Mars 2020.

Impact site characteristics. Table 2 reports the measurements of crater diameters. Craters CBMD-c and CBMD-e are nearly identical in diameter, which would be expected if two identical projectiles impacted the same target with identical velocities and impact angles. We also analyzed their ejecta radii and median absolute deviation as measures of asymmetries [7] (Table 2, Figure 2) to assess the impact sites similarity. However, ejecta patterns are not identical, possibly due to different topography.

Target properties. Preliminary calculations with pi scaling for sand or cohesive soil [8] place the strength parameter in the scaling relationship in the range 50-200 kPa, depending on the vertical component of the impact velocity, which is constrained to within a factor of two. More detailed results that follow from impact simulations are underway.

Preliminary conclusions

The fragmented cruise stage complicated the identification of craters excavated by ballast masses. We present several arguments that enabled us to distinguish CBMD craters from those made by cruise stage fragments. This advancement opens up a possibility to better constrain the local subsurface rheology. We will present a more detailed analysis of target properties at the meeting, including simulations with iSALE shock physics code [9] which explore complex target structures appropriate for the geologic settings shaped by fluvial processes.

References: [1] Prieur et al. (2018), 10.1029/2017JE005463 [2] Sokołowska et al. (2024), 10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116150 [3] Sokołowska et al. (2025), 10.1029/2024JE008561 [4] Nelessen et al. (2019), 10.1109/AERO.2019.8742167 [5] Way et al. (2021), 10.2514/6.2022-0421 [6] Kirk et al. (2021), 10.3390/rs13173511 [7] Gao & Sokołowska LPSC 2025, Abst.#2692 [8] Housen & Holsapple (2011) Icarus, 211, 1, 856-875. [9] Wünnemann et al. 2006. Icarus 180: 514–527.

Acknowledgements: This work is funded by a UKRI Horizon Europe Guarantee EP/Z003180/1. Special thanks to D. Way, B. Fernando and A. Chen for useful discussions.

How to cite: Sokolowska, A., Daubar, I., Collins, G., and Calef, F.: Solving the puzzle of too many craters from hardware impacts of Mars 2020, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1780, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1780, 2025.

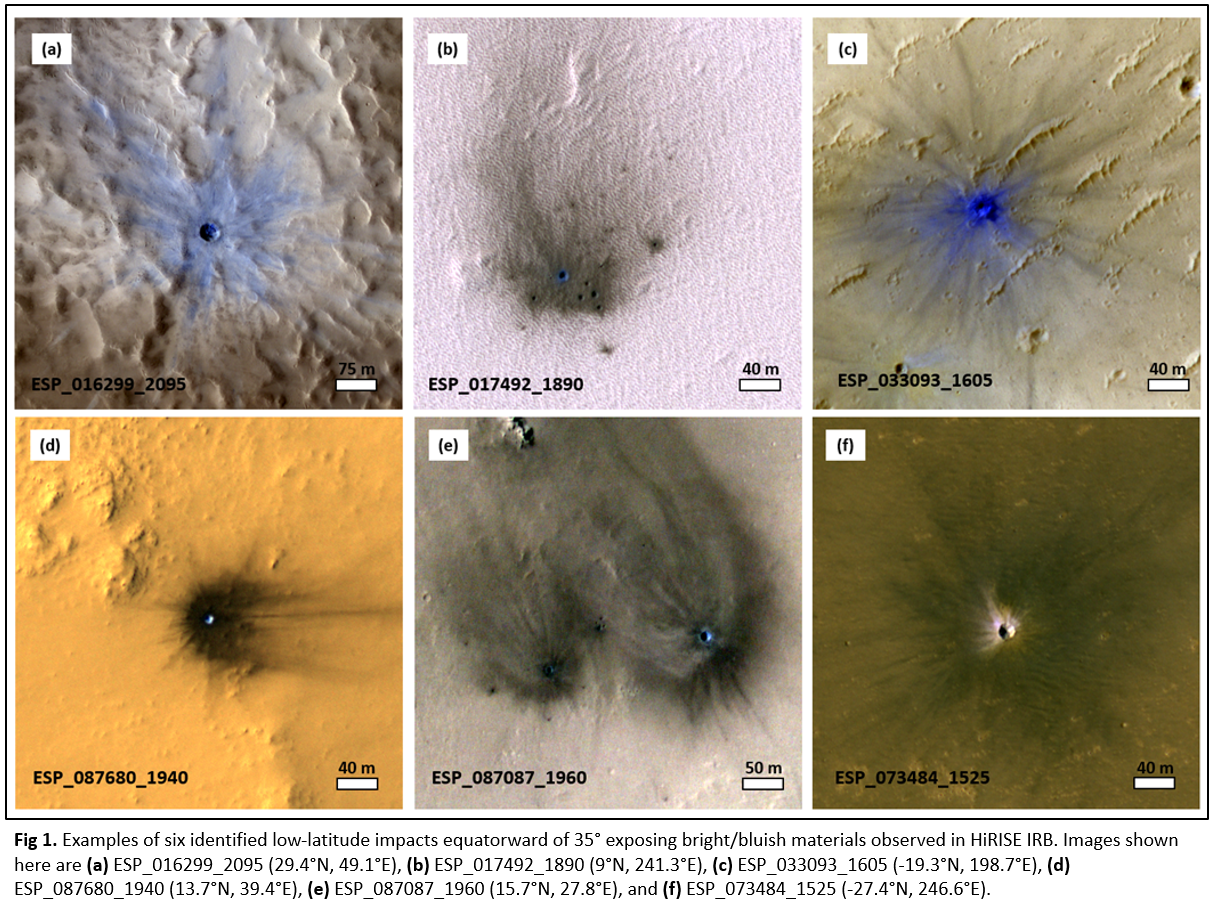

Titan's surface is covered by a thick atmosphere, much of which remains unexplored. Radar observations by the Cassini mission (2004‒2017) captured high-resolution images of approximately 69% of the surface, revealing a landscape rich in methane seas and rivers, with both dry and wet regions. Notably, Titan's surface has very few impact craters, which is the main geological feature used to estimate past impact fluxes or surface ages through crater

size-frequency distributions (CSFDs). This scarcity of craters is not only due to atmospheric shielding, which prevents many meteorites from reaching the surface, but also because Titan's surface, particularly the wet regions saturated with methane, is subject to intense erosion and

sediment deposition [1].

Wood et al. (2010) identified 49 possible impact craters across 22% of Titan's surface and reported that these features had been modified by various processes, including fluvial erosion, mass wasting, burial by dunes, and submergence in seas [2]. As a result, estimating surface

age from CSFDs is particularly challenging on Titan. Alternatively, Neish et al. (2013) and Rossignoli et al. (2022) proposed estimating surface age using impactor size-frequency distributions (SFDs) [3, 4]. Rossignoli et al. (2022) modelled the impactor SFD reaching Titan's surface under the assumption that most impactors originated from the Centaur population. Their analysis incorporated atmospheric shielding and used crater scaling laws

for icy targets to relate impactor size to crater size.

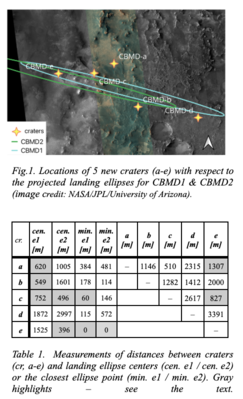

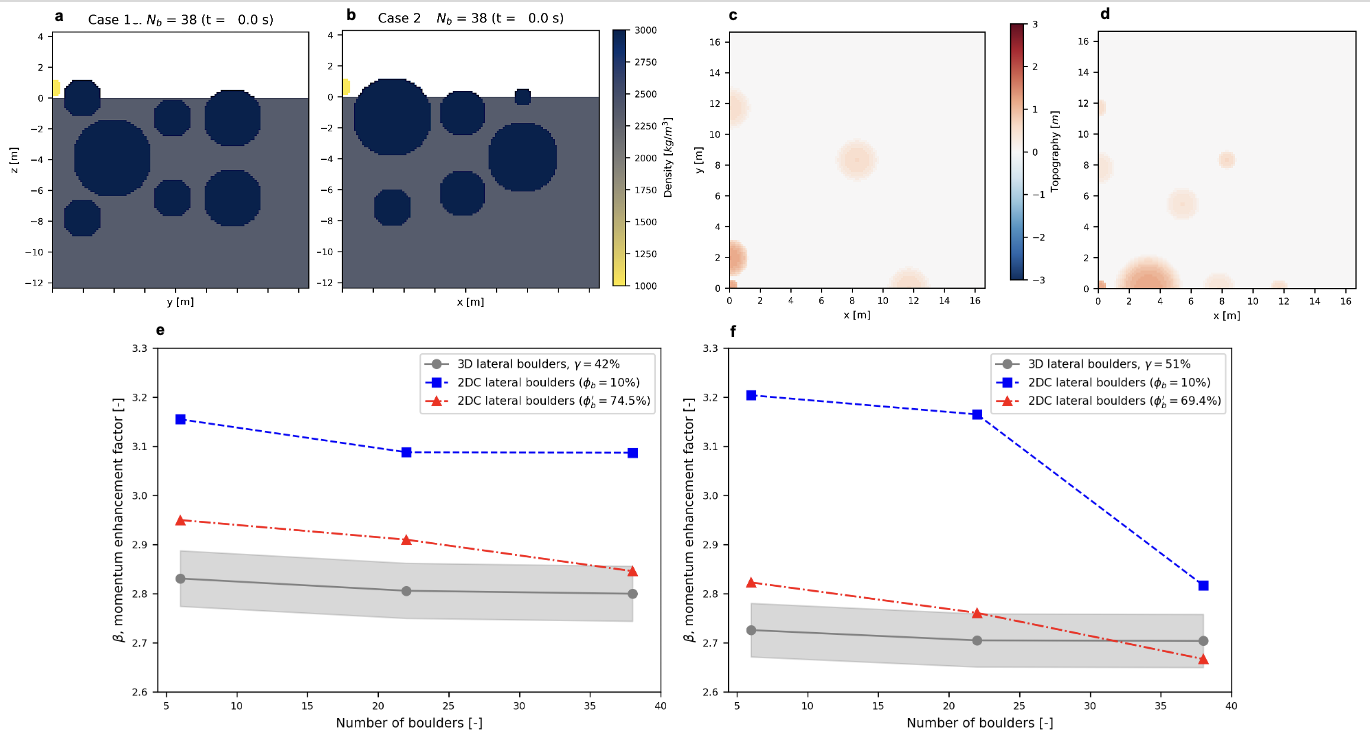

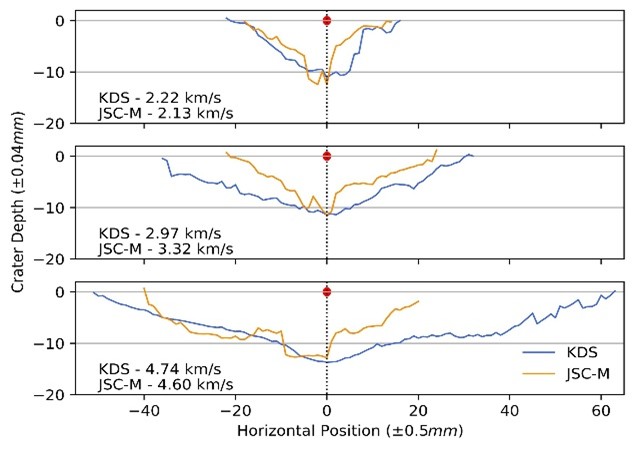

However, Titan's surface often retains liquid methane, which can alter key physical properties relevant to crater formation, such as friction, cohesion, and porosity. In this study, we conducted high-velocity impact experiments on wet sand targets with varying water contents to establish a crater size scaling relationship for wet surfaces, taking into account the effects of liquid content. Although Titan's wet surface would be composed of ice particles containing liquid methane, wet sand could serve as a suitable analogue, exhibiting similar physical characteristics during a cratering process. Using the impactor SFD proposed by Rossignoli et al. (2022), we estimated the original CSFD on Titan prior to erosion, enabling comparison with the currently observed CSFD to assess erosional effects on crater retention. Additionally, we performed numerical simulations to reconstruct the original morphology of Titan's craters before erosion and compared these with crater profiles observed by Cassini's Synthetic Aperture Radar to evaluate the degree of erosional modification.

Impact experiments: We conducted high-velocity impact experiments on wet sand targets using two-stage horizontal and vertical light gas guns at Kobe University and ISAS (JAXA). We used spherical aluminum or polycarbonate projectiles with the diameters of 2.0 mm or 4.7 mm. The impact velocities were 2-6 km/s. For the horizontal gas gun, the targets were tilted at 30°from the horizontal plane to simulate oblique impacts, while for the vertical gas gun,

targets were placed horizontally to simulate vertical impacts. The targets consisted of a homogeneous mixture of quartz sand (average grain size: 500 μm)

and water in varying proportions. For impacts with 2.0 mm projectiles, the mixture was placed in acrylic containers measuring 150 mm × 150 mm × 50 mm; for 4.7 mm projectiles, containers measured 200 mm × 200 mm × 100 mm. The water content was varied from 0 to

13 wt.%, which reduced the target porosity from 47% to 21% as water filled the pore spaces.

All experiments were recorded using two high-speed cameras. After impact, the final crater profiles were measured using either a 3D scanner or a 2D laser displacement indicator (Fig.1). These profiles were then used to calibrate our numerical model.

Fig. 1: 3D crater profiles from experiments on wet sand with varying water contents (wt%) showing distinct crater morphologies.

Numerical models: We use Bern's parallel Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics (Bern SPH) impact code [5, 6] to reproduce and extend our experimental results. This SPH code has been previously validated against laboratory experiments, including quartz sand targets [e.g., 7, 8].

Results and Discussion: The craters formed in our experiments were influenced by changes in target water content, affecting not only cohesion but also the coefficient of friction. We established a crater size scaling relationship for wet sand by accounting for these water content effects, using the π-scaling framework developed by Housen and Holsapple (1993):

Where with crater radius R, target density ρ , projectile mass m, gravitational acceleration g, projectile radius a, impact velocity U, impact angle θ, and water content wc. For a detailed derivation of our scaling relationship,

see Toyoshima et al. (2024) [9].

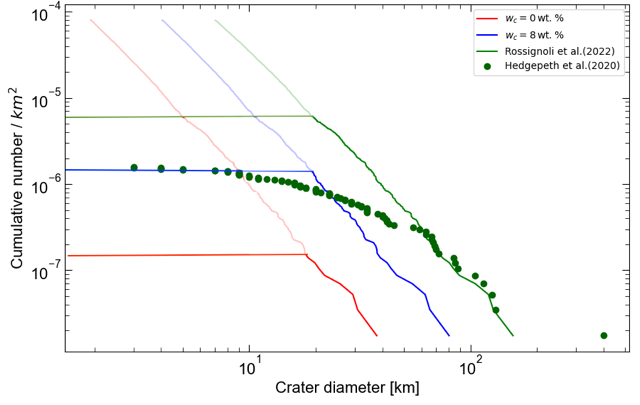

We used the impactor SFD from Rossignoli et al. (2022), which follows a broken power-law model for Centaur objects, to calculate the expected original CSFD on Titan (Eq. 2; C0=3.5 ×105×100(s2-1), s1=4.7, s2=3.5). They also included the atmospheric effects such as deceleration and ablation of impactors, and concluded that CSFD would become constant at crater size < 25 km. Figure 2 shows that the CSFDs for our scaling relationship is less than that for Rossignoli et al. (2022), and also it differs by approximately an order of magnitude between wet and dry targets. This suggests that the CSFD would indicate a younger surface age than previously estimated if we use our scaling relationship, and the estimated age would vary with surface liquid content. Further analysis is needed to refine the application of the impactor SFD. In our presentation, we will discuss the estimated surface age of Titan, crater retention ages, and the erosional effects on crater morphology. Eq.(2)

Fig. 2: Crater size-frequency distributions (CSFDs) on Titan for an icy target (from Rossignoli et al. (2022)) and for targets with varying water content (wt%) (this study). These CSFDs were calculated using the impactor size-frequency distribution from Rossignoli et al. (2022). Green markers indicate the observed CSFD from Hedgepeth et al. (2020) [10].

Citation:

[1]Cornet et al. (2015). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 120(6), 1044‒1074.

[2] Wood, C.A., et al. (2010). Icarus, 206, 334‒344.

[3] Neish, C.D., et al. (2013). Icarus, 223(1), 82‒90.

[4] Rossignoli, N.L., et al. (2022). A&A, 660, A127.

[5] Jutzi, M., et al. (2008). Icarus, 198, 242‒255.

[6] Jutzi, M. (2015). PSS, 107, 3‒9.

[7] Ormö, J., et al. (2022). EPSL, 594, 117713.

[8] Raducan, S.D., et al. (2021). LPSC, #1908.

[9] Toyoshima, H., et al. (2024). JGR-Planets, submitted.

[10] Hedgepeth, J.E., et al. (2020). Icarus, 344, 113664.

How to cite: Toyoshima, H., Raducan, S., Arakawa, M., Hasegawa, S., and Jutzi, M.: Impact cratering on wet surface : Implications to the erosional degree on impact craters on Titan , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-285, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-285, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

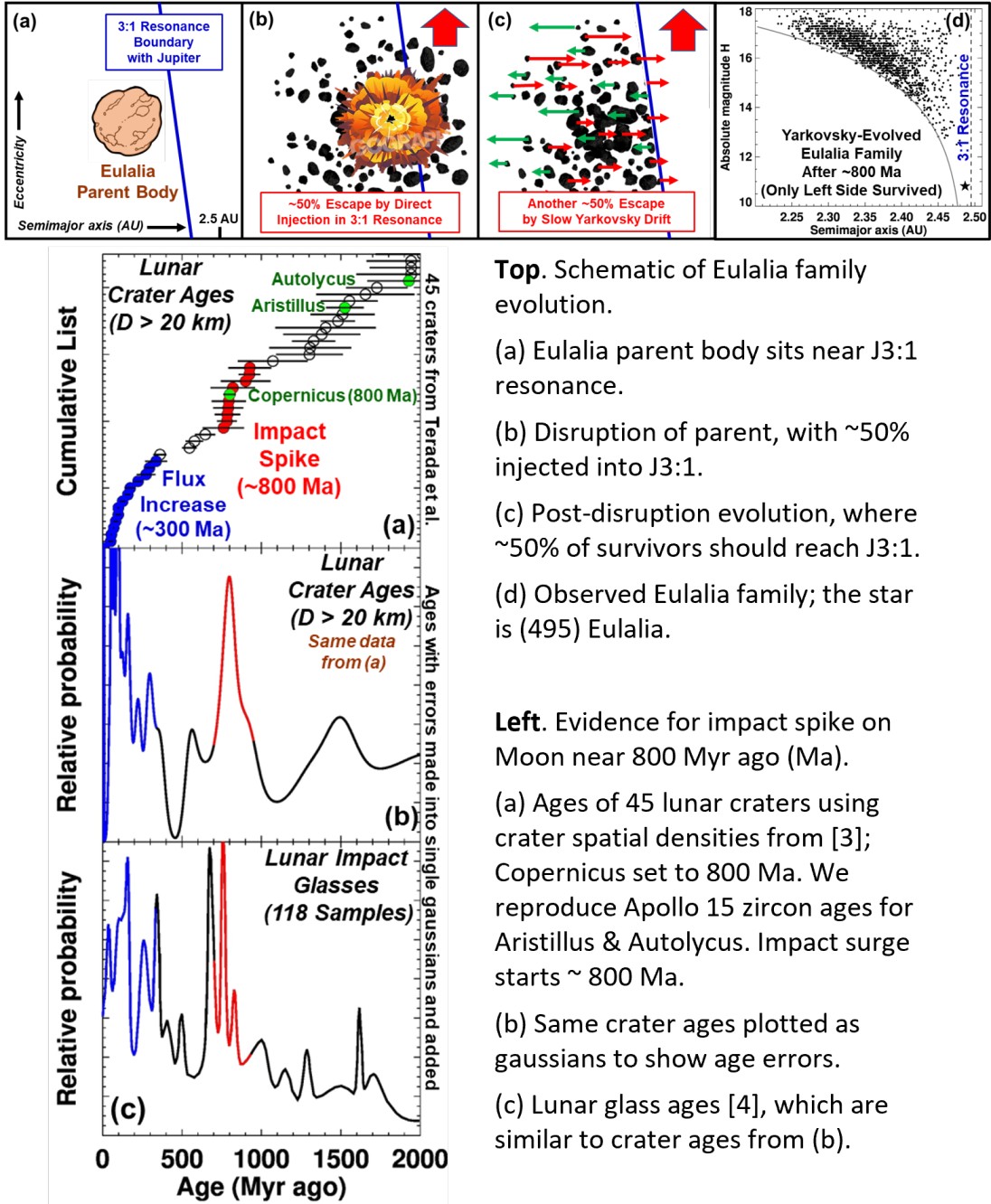

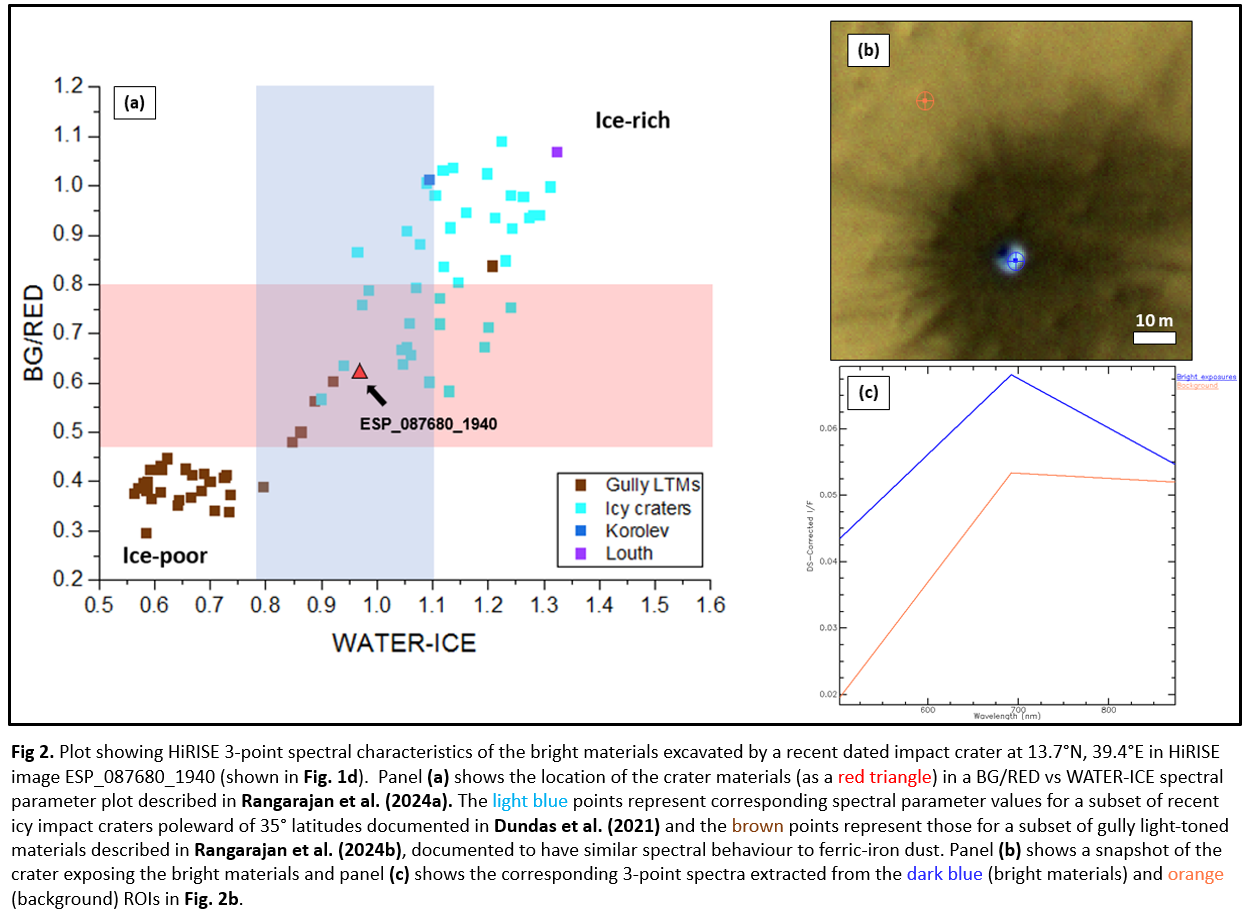

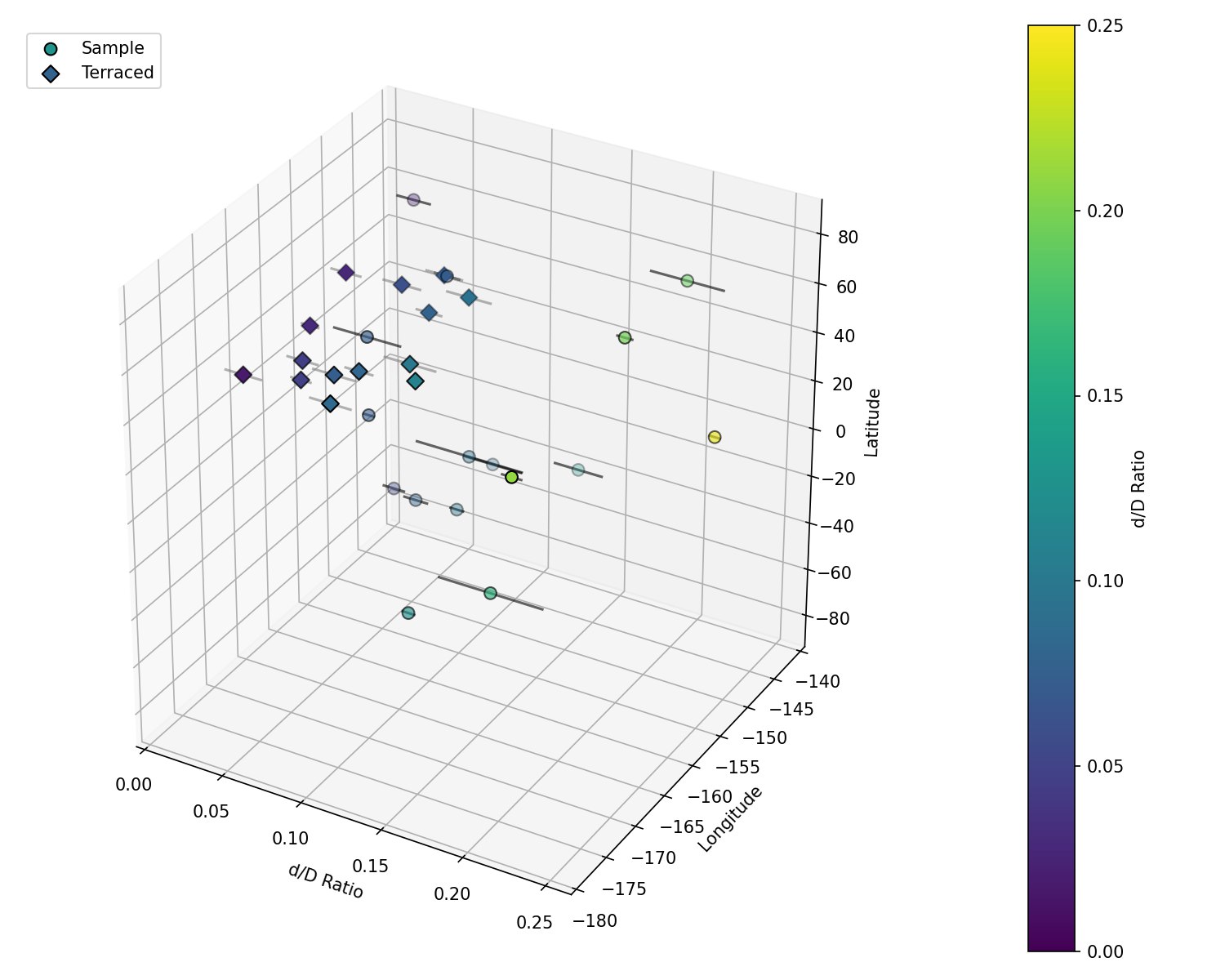

Many assume that inner solar system impact rates have been constant for the last ~3 Gyr (e.g., [1]). The evidence for a constant flux, however, is based on the spatial densities of small craters (Dcrater < 1-2 km diameter) superposed on dated lunar terrains [2]. While these data constrain the flux of small asteroids (D < 0.1 km), they are less predictive of the large impactor flux, which may be driven by surges. For example, [3] measured the spatial densities of Dcrater < 0.1-0.2 km craters on the ejecta blankets of 59 fresh lunar craters with Dcrater > 20 km; 45 are shown in the Left Fig. By setting Copernicus crater (Dcrater = 93 km) to be 800 Myr old (Ma), based on Apollo 12 data [2], crater spatial densities can be turned into ages (Left Fig). Their results suggest a prominent lunar shower occurred ~800 Ma. Similar trends are found in the 40Ar/39Ar age profiles of 118 lunar impact glasses [4] (Left Fig). The match between crater and impact glass ages provides support for the work of [5], the first to argue for a lunar impact spike ~800 Ma. They also indicate lunar impact glass ages are less biased than previously thought (e.g., [6]).

Using collisional/dynamical models [e.g., 7], we can now reproduce this impactor surge from the formation of the Eulalia asteroid family, whose D > 100 km parent body disrupted on the brink of the 3:1 mean motion resonance with Jupiter (J3:1) ~ 800 Ma (Top Fig). This rare occurrence allowed roughly half the family to be injected into the J3:1, with additional members migrating in later by Yarkovsky drift. Ultimately, approximately three-fourths of this family reached the J3:1 over a roughly ~100 Myr interval, enough to explain the size and number of large lunar craters with ages near 800 Ma.

Note that for every impact on the Moon, ~twenty same-sized or larger impacts strike Earth. We find this bombardment intriguing because several sudden transitions in our biosphere occur near 800 Ma. Some examples include: (i) the return of anoxic conditions to the deep ocean for the first time since ~1.8 Ga [8], (ii) an abrupt decrease in carbon isotopes (δ13C) in Australia’s Bitter Springs formation (e.g., [9]), and (iii) major changes in the abundance, diversity, and environmental distribution of marine eukaryotes [10]. We speculate that major terrestrial impacts near this time from Eulalia projectiles might have stimulated such activity. If true, it can be argued that the Eulalia family forming event strongly influenced the evolution of life on Earth. We also point out that Martian caldera ages, dated using superposed craters, show hints of clustering near 800 Ma. If so, Eulalia impacts may also be responsible for a short-term increase in Martian volcanism near that time.

[1] Neukum, G. et al. 2001. Space Sci. Rev. 96, 55. [2] Stöffler, D., Ryder, G. 2001. Space Sci. Rev. 96, 9. [3] Terada, K. et al. 2020. Nature Comm. 11, 3453. [4] Ghent, R. R., & N. E. B. Zellner. 2020. White Paper for the Planetary Decadal Survey. [5] Zellner, N. E. B., et al. 2009. GCA 73, 4590. [6] Huang, Y.-H. et al. 2018, GRL 45, 6805; [7] Bottke, W. F. 2015. Icarus 247, 191-271. [8] Canfield, D. E. et al. 2008. Science 321, 949. [9] Wörndle et al. 2019. Chem. Geo 524, 119. [10] Knoll A. H. 2014. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 6, a016121.

How to cite: Bottke, W., Vokrouhlický, D., and Dykhuis, M.: An Impact Shower on the Earth, Moon, and Mars from 800 Million Years Ago, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-428, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-428, 2025.

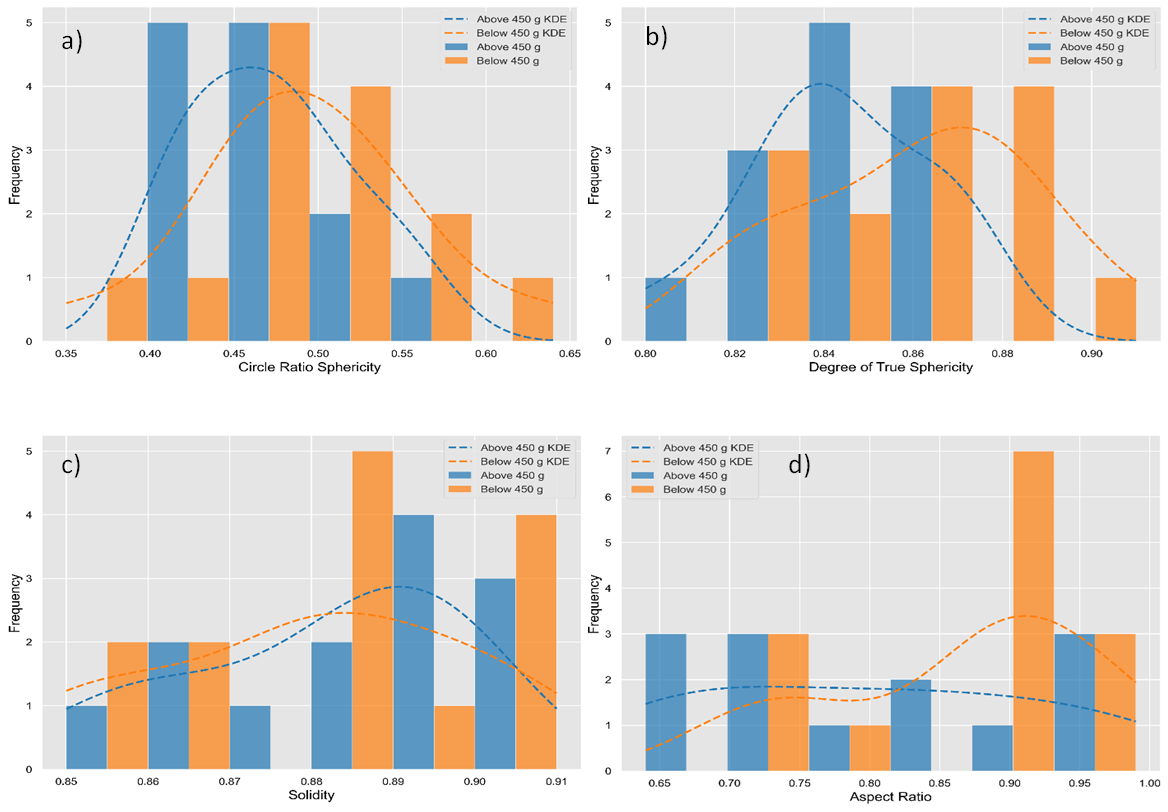

Impact fragment size distribution is a vital factor in understanding impact processes and evaluate impact consequences. Thousands of meteoroids enter the Earth's atmosphere, but most of them burn up due to frictional heat, yet a small fraction survive to reach the ground as meteorites. The Bjurböle meteorite presents a valuable research opportunity as one of the few meteorites that remained significantly fragmented after impact. This approximately 400 kg L/LL ordinary chondrite meteorite's impact on sea ice resulted in catastrophic disruption, producing numerous centimeter to decimeter-sized fragments. This size range is underrepresented in both impact experiments and asteroid boulder studies and is often subject to observational bias in asteroid boulder studies. Consequently, the fate of centimeter to decimeter-sized particles from impact disruption remains poorly understood, while comprehensive 3D analyses of asteroid boulder morphology, examining both shape and size distribution concurrently, remain limited. To address this deficiency, we examined digital shape models of Bjurböle fragments weighing between 0.01 and 1 kg. The resulting 3D models were subsequently analysed for shape characteristics and morphology using a MATLAB-based analytical pipeline. Detailed 3D morphological parameters were studied, including bounding box dimensions (a, b, c), aspect ratios (b/a, c/a, c/b), equivalent diameter, circle ratio sphericity, degree of true sphericity, and solidity. Additionally, we compared 2D and 3D morphological analyses on the same fragment models to understand analytical variations between the approaches. Notably, the 3D analysis revealed more pronounced irregularities compared to 2D analysis because it comprehensively accounts for all surfaces in morphological determination, providing a more complete and comprehensive representation of the fragments' true geometric complexity. Results indicated mean fragment aspect ratios (b/a: 0.85 ± 0.09; c/a: 0.67 ± 0.13) indicating relatively equidimensional shapes, especially in the a-b plane. 3D morphological parameters such as degree of true sphericity (equivalent to circularity in 2D), as a large-scale roughness indicator, was determined to be 0.83 ± 0.04. Similarly, solidity, an indicator of small-scale roughness, was determined to be 0.88 ± 0.02, suggesting that Bjurböle meteorite fragments are generally exhibit convex shapes with noticeable concavities. Smaller fragments displayed reduced roughness with fewer concavities, while bigger fragments exhibited increased surface roughness with more prominent convex hulls, characteristics potentially attributable to fusion crust and erosion processes.

References: Kohout et al. (2024) DOI https://doi.org/10.3847/PSJ/ad4266

Fig. 1. Histograms of dimension ratios b/a, c/a, and c/b of studied fragments from the Bjurböle meteorite, comparing size fractions below 450g (right) and between 450g and 1kg (left).

Fig. 2. Histograms with Kernal density estimation of a) circle ratio sphericity, b) degree of true sphericity, c) solidity and d) aspect ratio obtained using 3D morphological analysis for Bjurböle meteorite fragments weighing below 1 kg. Blue: Above 450 g size fraction, orange: below 450 g size fraction, dash lines: Kernal density estimations.

How to cite: Kohout, T., Seemantha Aachchi, R., Luttinen, A., and Duchene, A.: 3D shape and size distribution of Bjurböle chondritic meteorite fragments from a catastrophic impact event, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1744, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1744, 2025.

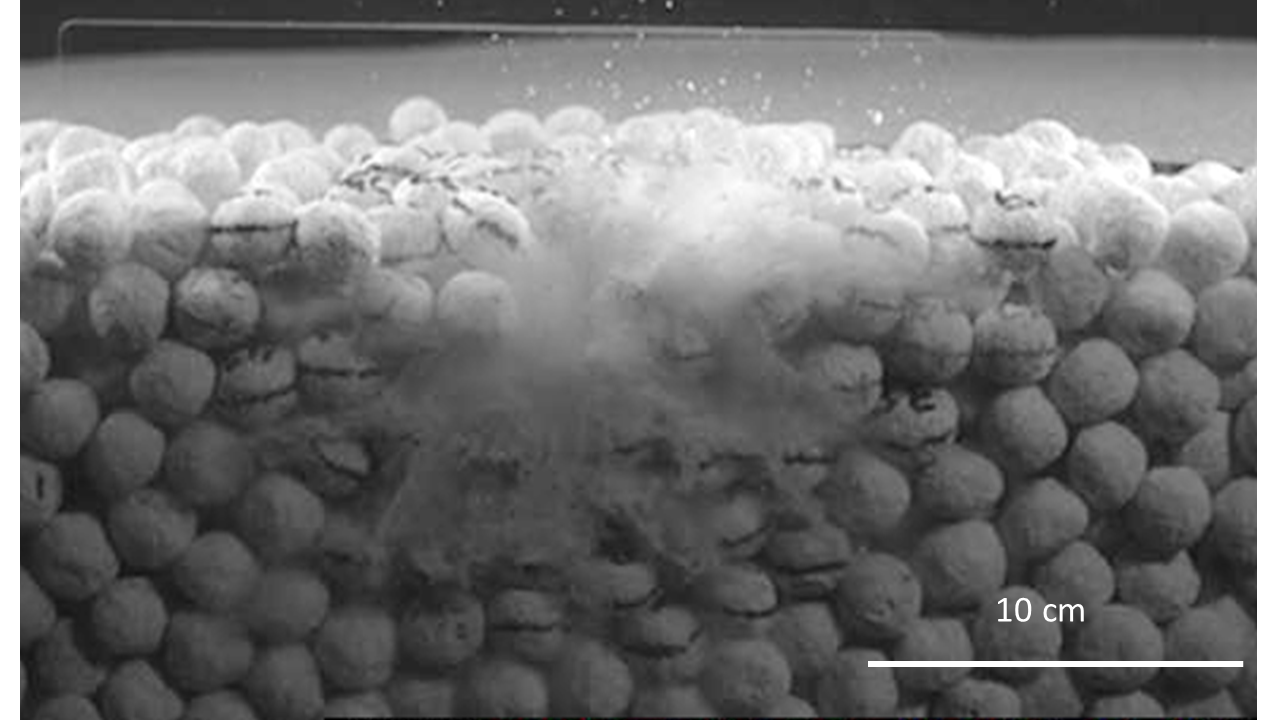

The "rubble-pile" structure of several asteroids recently examined by space missions—such as Dimorphos, Itokawa, Bennu, and Ryugu—has drawn significant attention to these types of celestial bodies. However, their internal composition remains largely uncertain, but a strength-stratification with a weaker exterior compared with the interior has been suggested for at least some of them (e.g., Daly et al. 2022). To explore a possible explanation for this strength stratification in rubble-pile asteroids, an impact experiment was conducted at the Experimental Projectile Impact Chamber (EPIC) at Centro de Astrobiología (CAB), CSIC-INTA, Spain (cf. Ormö et al., 2015). The target was prepared in a 60 ‐cm wide, half‐spherical metal bowl that had been cut in half and mounted to the camera chamber window for quarter space setup. The bowl was filled with porous, ceramic balls of nearly equal diameter and density as the projectile, which were of the polymer Delrin (20mm diameter, 5.7g) impacting vertically at ̴0.4km/s. High-speed video recordings showed that crushed target and projectile material rapidly penetrates deep into the substrate, dispersing radially beneath the crater floor (Fig. 1). If such impacts occur repeatedly over time in a porous and easily crushable material, this process could lead to the accumulation of fine-grained, compacted, and increasingly cohesive material at deeper layers. Meanwhile, impact-induced seismic activity on the asteroid, causing granular convection (the "Brazil Nut Effect"), along with rotational centrifugal forces, could promote the segregation of finer material beneath coarser layers—potentially making this effect more pronounced at the poles.

Fig. 1. Radial clastic injections of crushed impactor and target material shortly after impact into a "boulder" target. Also note the poor development of an excavated cavity in this porous target.

References

Daly, T. R., et al. (2022), Icarus 384, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115058

Ormö, J. et al., (2015), Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 50(12), https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12560

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by grant PID2021-125883NB-C22 by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation/State Agency of Research MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by ‘ERDF A way of making Europe’, and Spanish National Research Council CSIC (Project ILINK22061). SDR, MJ, RL and KW have received funding from the EU’s H2020, grant agreement No. 870377 (NEO-MAPP). SDR. and MJ acknowledge support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (project number 200021_207359).

How to cite: Ormö, J., Herreros, I., Luther, R., Wünnemann, K., Raducan, S., and Jutzi, M.: Impact-Generated Clastic Injections as a Cause for Stratification in Rubble-Pile Asteroids, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-348, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-348, 2025.

Metal asteroids are a topic of increasing interest within both the public and private space sectors, as the in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) and asteroid mining communities continue to develop and expand. The metal asteroid 16 Psyche is the largest known M-class asteroid in the main asteroid belt and thus can be considered a prime target for further investigation, with upcoming activities including the NASA Psyche mission which is due to arrive in 2029.

Despite this heightened level of interest, many fundamental unknowns remain about 16 Psyche. The limited existing data from ground-based telescopes has resulted in an estimated composition of 30-60% metal (predominantly iron and nickel) and the remaining material as silicate rock. However, both the physical properties —including detailed composition, grain size, material compaction— and behaviours —for instance, response to micrometeorite impacts and ion irradiation— of the surface material remain unknown.

This research, conducted at ESA’s Vulcan Analogue Sample Facility, aims to better understand the impact processes on 16 Psyche and their influence on the presence (or lack thereof) of a surface regolith. Hyper velocity impact experiments will be conducted using the two-stage gas gun at the University of Kent. Small copper projectiles (~2mm) will be fired at a metal meteorite to determine if the large metal crystals present will shatter and be comminuted —thus contributing to a metal rich surface regolith—, or if they will instead melt and remain coherent —therefore not significantly contributing to a surface regolith.

In doing so, we aim to predict the composition and physical structure of 16 Psyche’s surface material. Drawing on previous hypervelocity experiments, we hypothesize that upon impact the crystals will shatter and produce a loose regolith-like material. If this is the case, there are likely to be positive implications for future asteroid mining activities due to the ease of metal extraction from regolith compared to impact-melt crusts.

An estimation of this surface material will enable further, more complex surface research of 16 Psyche, and most importantly for the Vulcan Facility, underpin the development and production of surface simulants of the asteroid. It may also contribute to derisking any future landers, as well as improving the understanding of its utilization potential for resource extraction on Psyche and other metal asteroids. Beyond this, we hope our research can help inform a deeper understanding of the processes of formation and weathering of metal asteroids.

How to cite: Vosper, D., Martin, M., Wozniakiewicz, P., and Manick, K.: Experimental investigations of impact processes on the metal asteroid 16 Psyche, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1917, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1917, 2025.

Introduction

Impacts drive regolith formation and modification on asteroids (Shoemaker et al., 1969) through bedrock excavation, fragmentation, and the deposition of ejected material back onto the surface (Melosh, 2011). Over time, impacts gradually increase the regolith depth. Eventually, the regolith becomes sufficiently thick that only large impactors produce craters that penetrate into the underlying bedrock, generating new regolith. This enables the depth of the regolith layer to serve as an indicator of a surface's exposure age to the impactor flux, if one understands the cratering process on these bodies (Richardson et al. 2020).

The regolith depth can be directly measured from subsidence pits on asteroids, which form when a fault or fracture opens up beneath the regolith layer, allowing loose regolith to subside and flow into the fracture (Horstman and Melosh, 1989). The shape and size of the resulting subsidence pit at the surface are determined by a cone extending upward from the fissure at an angle determined by cohesion and the angle of internal friction; as material drains into the fissure, it forms the shape of this cone (Melosh, 2011). Thus, simple trigonometry enables the thickness of the regolith to be determined from the dimensions of subsidence pits. Using this approach, Horstman and Melosh (1989) found that the regolith of Phobos is 290-300 m thick, and Richardson et al. (2020) determined that the regolith of Šteins is 145±35 m thick.

Using an accurate model of the asteroid cratering flux over time, the cratering process itself, and knowledge of how seismic waves propagate and degrade cratered terrain, one can use numerical simulations to calculate how long it takes for such a regolith depth to develop. Richardson et al. (2020) applied this technique to asteroid 2867 Šteins, finding that, although its cratering record suggests a minimum Main Belt Exposure Age (MBEA) of 175±25 Myr, the regolith depth requires a much longer MBEA of 475±25 Myr. They also found that the cratering record of 433 Eros suggests an MBEA of 225±75 Myr.

The surface of 433 Eros also has subsidence pits, enabling a proper estimate of the regolith depth across Eros and its corresponding minimum MBEA. In this work, we apply this technique to measure Eros’ subsidence pits to map the regolith thickness, calculate its minimum MBEA based on regolith depth, and then compare this with the cratering MBEA.

Methods and Results

Using the Small Body Mapping Tool (SBMT), we selected images from the NEAR Mapping Spectrometer Instrument (MSI) to identify, map, and measure pit chains on Eros using a variety of search parameters (spatial resolution, wavelength filter, limb inclusion, incidence angle, emission and phase angle). Among the seven filters of MSI spanning the VIS-NIR range (450-1050 nm), filter 4 contained over 80% of the images, which were the focus of this study. The following parameters were found to be ideal: resolution ≤ 5 m/pixel, both with and without limb, an incidence range of 10˚-70˚, an emission range of 10˚-70˚, and a phase range of 20˚-140˚.

Using select MSI images over the entire body, individual pits were mapped with circles, and their diameter and location were recorded. We then refined the number of pits using a larger number of images, and as a final check, performed a second refinement using a global basemap that is included in SBMT. We identified a total of 330 pits as well as 60 distinct chains.

|

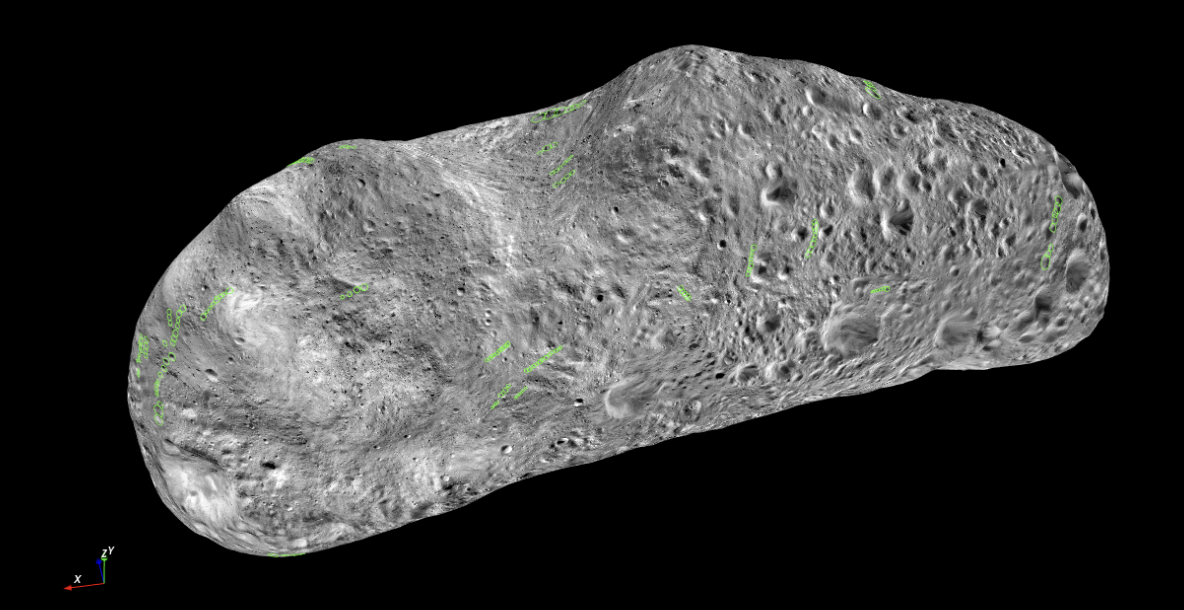

Fig. 1. 433 Eros displayed in SBMT software with measured pit chains denoted by green circles. |

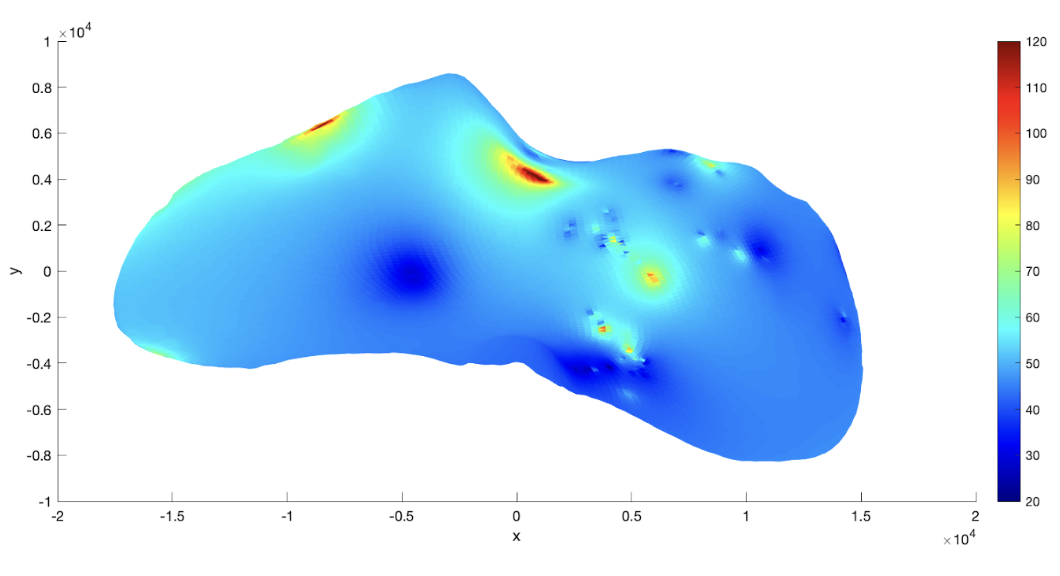

To produce a map of the regolith depth across Eros, we assumed that the depth varied smoothly and linearly between measurement points, such that the depth of the regolith at a particular facet is computed by the average of each measured pit crater, weighted by the square of the distance between facet and pit. We assumed an angle of internal friction of 35 degrees and zero cohesion, and used the Gaskell (2008) shape model to map the regolith depth (Figure 2). We find that Eros has an average regolith depth of ~48m.

|

|

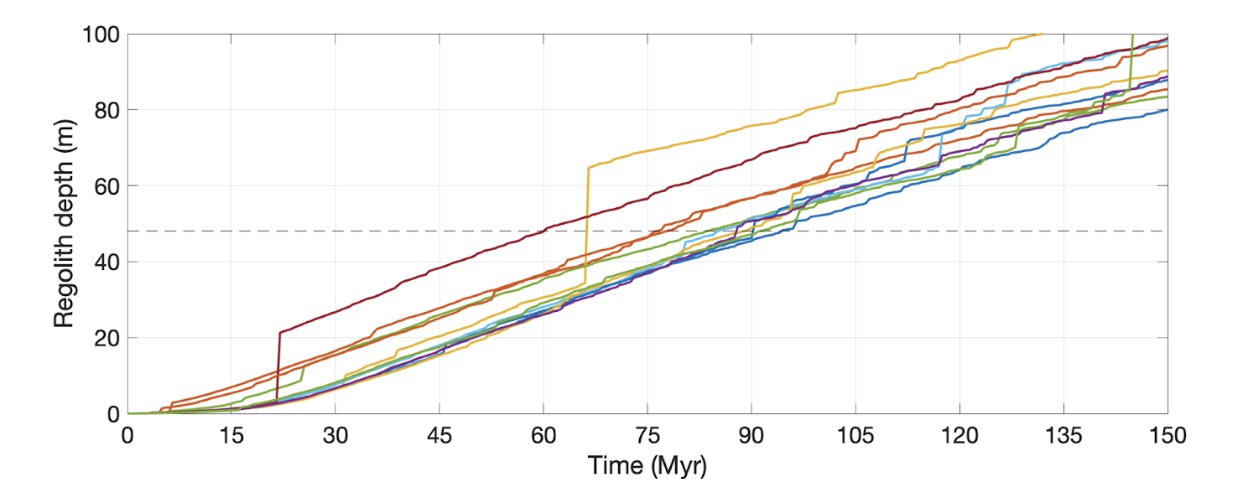

To determine the MBEA based on regolith depth, we model Eros in SB-CTEM; we assume the same strength, seismic, and material properties for Eros as Richardson et al. (2020), and the impactor flux from Bottke et al. (2005). We find that 48m of regolith requires ~60-94 Myr, with an average of ~82 Myr (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Regolith depth over time in our 11 SB-CTEM simulations. Simulations “move” together and slowly disperse over time due to the effects of rare, large impacts, which cause regolith depths to “jump” stochastically. |

Discussion

This MBEA of ~82 Myr for the regolith is a much younger age than previously estimated by Richardson et al. (2020). The age difference could be due to incomplete image coverage of subsidence pits and/or associated errors with measuring distance across the surface of an irregular object. Further refinement of material properties may also close the gap between the MBEAs of the regolith and craters.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NASA DDAP grant 80NSSC21K1014.

How to cite: Steckloff, J., Richardson, J., Berman, D., and Chuang, F.: The Thickness and Age of Asteroid 433 Eros’ Surface Regolith, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1225, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1225, 2025.

Impact cratering is one of the primary processes influencing major landscape evolution on an asteroid’s surface. The largest craters offer a unique natural laboratory to investigate an asteroid's interior structure through the exhumation and redistribution of material via hypervelocity impacts. Metal-rich asteroids, thought to be the leftover cores of differentiated planetesimals [1], exhibit variable metal concentrations indicated by radar albedo measurements, and heavily cratered surfaces; however, a detailed understanding of their collisional modification is currently a key unanswered question. In addition, several of the M-types in the main belt, such as asteroid (16) Psyche, (216) Kleopatra, and (22) Kalliope, have rapid spin rates [2, 3]. As previously shown for asteroid (4) Vesta, ejecta deposition is not hemispherically symmetric when the target is rotating before impact [4]. Instead, the ejecta is deposited over multiple rotations, and the majority of the ejected material is reaccumulated by the asteroid, which may form features like folds and thrusts on the surface of the body. In this work, we demonstrate how the formation of large impact craters on metal-rich worlds, through hydrocode modeling, can provide the foundational framework for understanding their surface and interior morphology, including the influence of pre-impact rotation.

We have developed a workflow using the realistic shape models of asteroids, with asteroid (16) Psyche as an example, to conduct our high-resolution impact simulations, as we find that asteroid shape combined with pre-impact rotation plays a critical role in influencing the final ejecta distribution. Our 3D models use the Bern SPH code [5], which incorporates detailed and validated material treatments, including a strength and cohesion model, and a robust P-α porosity model, subject to a crushing curve [6, 7].