- 1Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, Arizona, USA

- 2University of Texas at Austin, Department of Aerospace Engineering and Engineering Mechanics, Austin, Texas, USA

Introduction

Impacts drive regolith formation and modification on asteroids (Shoemaker et al., 1969) through bedrock excavation, fragmentation, and the deposition of ejected material back onto the surface (Melosh, 2011). Over time, impacts gradually increase the regolith depth. Eventually, the regolith becomes sufficiently thick that only large impactors produce craters that penetrate into the underlying bedrock, generating new regolith. This enables the depth of the regolith layer to serve as an indicator of a surface's exposure age to the impactor flux, if one understands the cratering process on these bodies (Richardson et al. 2020).

The regolith depth can be directly measured from subsidence pits on asteroids, which form when a fault or fracture opens up beneath the regolith layer, allowing loose regolith to subside and flow into the fracture (Horstman and Melosh, 1989). The shape and size of the resulting subsidence pit at the surface are determined by a cone extending upward from the fissure at an angle determined by cohesion and the angle of internal friction; as material drains into the fissure, it forms the shape of this cone (Melosh, 2011). Thus, simple trigonometry enables the thickness of the regolith to be determined from the dimensions of subsidence pits. Using this approach, Horstman and Melosh (1989) found that the regolith of Phobos is 290-300 m thick, and Richardson et al. (2020) determined that the regolith of Šteins is 145±35 m thick.

Using an accurate model of the asteroid cratering flux over time, the cratering process itself, and knowledge of how seismic waves propagate and degrade cratered terrain, one can use numerical simulations to calculate how long it takes for such a regolith depth to develop. Richardson et al. (2020) applied this technique to asteroid 2867 Šteins, finding that, although its cratering record suggests a minimum Main Belt Exposure Age (MBEA) of 175±25 Myr, the regolith depth requires a much longer MBEA of 475±25 Myr. They also found that the cratering record of 433 Eros suggests an MBEA of 225±75 Myr.

The surface of 433 Eros also has subsidence pits, enabling a proper estimate of the regolith depth across Eros and its corresponding minimum MBEA. In this work, we apply this technique to measure Eros’ subsidence pits to map the regolith thickness, calculate its minimum MBEA based on regolith depth, and then compare this with the cratering MBEA.

Methods and Results

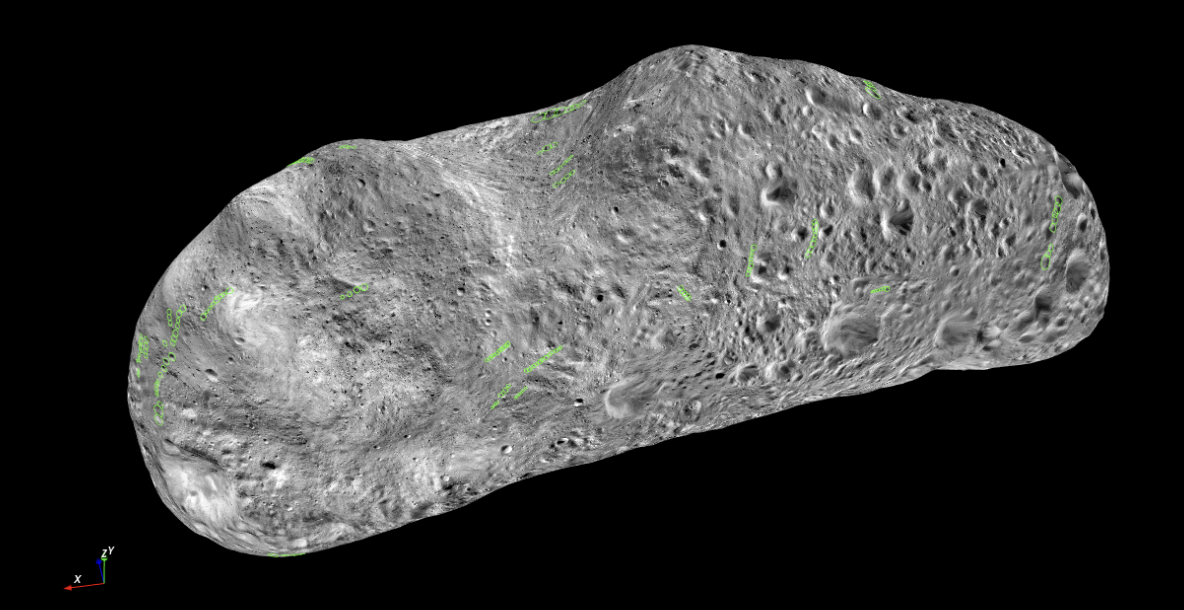

Using the Small Body Mapping Tool (SBMT), we selected images from the NEAR Mapping Spectrometer Instrument (MSI) to identify, map, and measure pit chains on Eros using a variety of search parameters (spatial resolution, wavelength filter, limb inclusion, incidence angle, emission and phase angle). Among the seven filters of MSI spanning the VIS-NIR range (450-1050 nm), filter 4 contained over 80% of the images, which were the focus of this study. The following parameters were found to be ideal: resolution ≤ 5 m/pixel, both with and without limb, an incidence range of 10˚-70˚, an emission range of 10˚-70˚, and a phase range of 20˚-140˚.

Using select MSI images over the entire body, individual pits were mapped with circles, and their diameter and location were recorded. We then refined the number of pits using a larger number of images, and as a final check, performed a second refinement using a global basemap that is included in SBMT. We identified a total of 330 pits as well as 60 distinct chains.

|

Fig. 1. 433 Eros displayed in SBMT software with measured pit chains denoted by green circles. |

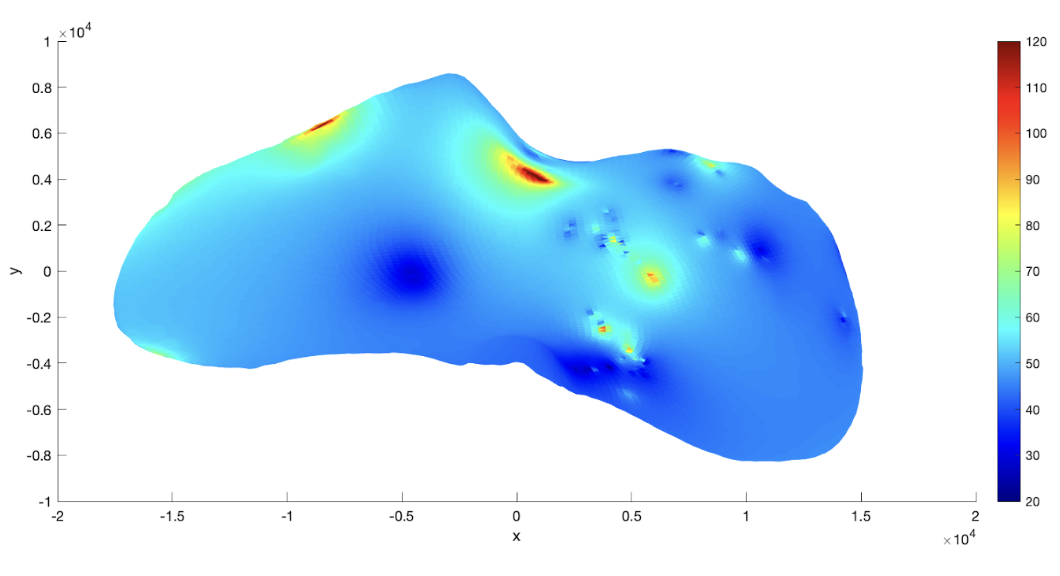

To produce a map of the regolith depth across Eros, we assumed that the depth varied smoothly and linearly between measurement points, such that the depth of the regolith at a particular facet is computed by the average of each measured pit crater, weighted by the square of the distance between facet and pit. We assumed an angle of internal friction of 35 degrees and zero cohesion, and used the Gaskell (2008) shape model to map the regolith depth (Figure 2). We find that Eros has an average regolith depth of ~48m.

|

|

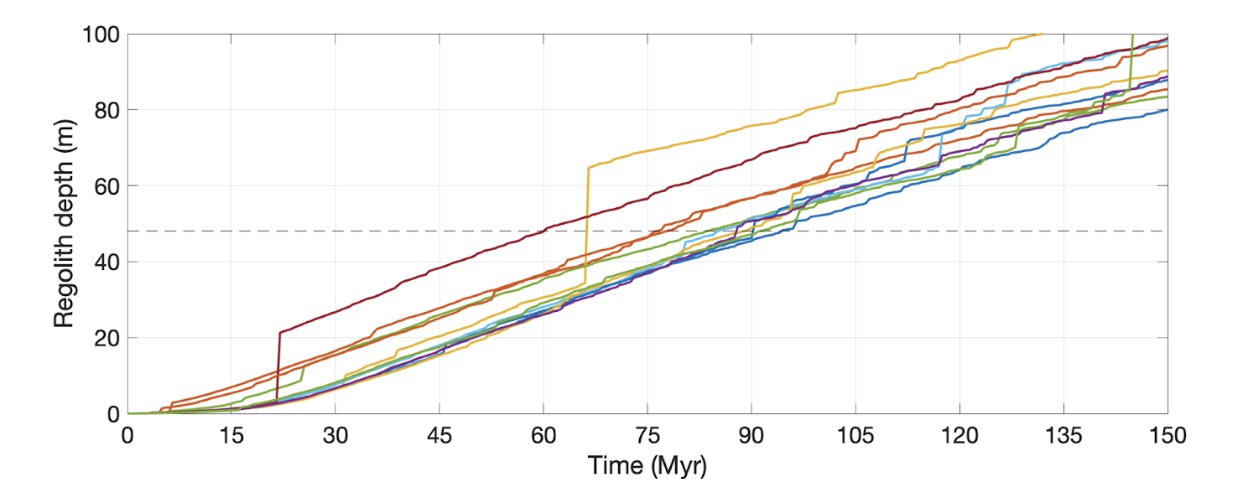

To determine the MBEA based on regolith depth, we model Eros in SB-CTEM; we assume the same strength, seismic, and material properties for Eros as Richardson et al. (2020), and the impactor flux from Bottke et al. (2005). We find that 48m of regolith requires ~60-94 Myr, with an average of ~82 Myr (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Regolith depth over time in our 11 SB-CTEM simulations. Simulations “move” together and slowly disperse over time due to the effects of rare, large impacts, which cause regolith depths to “jump” stochastically. |

Discussion

This MBEA of ~82 Myr for the regolith is a much younger age than previously estimated by Richardson et al. (2020). The age difference could be due to incomplete image coverage of subsidence pits and/or associated errors with measuring distance across the surface of an irregular object. Further refinement of material properties may also close the gap between the MBEAs of the regolith and craters.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by NASA DDAP grant 80NSSC21K1014.

How to cite: Steckloff, J., Richardson, J., Berman, D., and Chuang, F.: The Thickness and Age of Asteroid 433 Eros’ Surface Regolith, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1225, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1225, 2025.

Figure 2: A map of the regolith depth in meters across the surface of Eros.

Figure 2: A map of the regolith depth in meters across the surface of Eros.