- 1Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Paris, France (alexandre.gauvain.ag@gmail.com)

- 2Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Bordeaux, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France

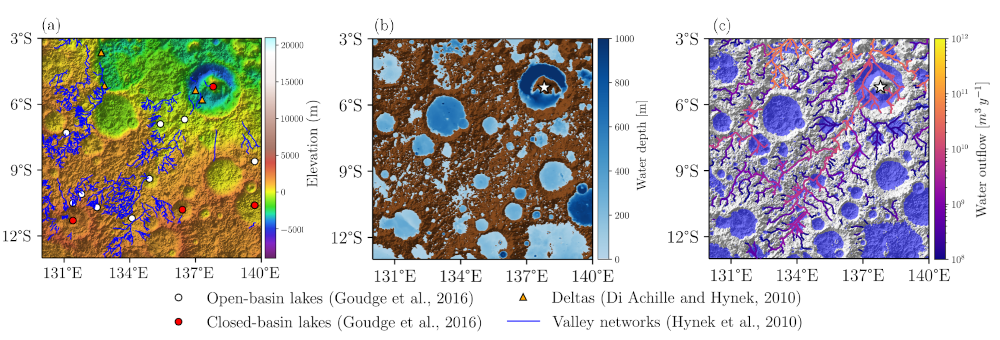

The ancient terrains of Mars, dating from the Noachian and early Hesperian epochs, display a variety of geomorphological and mineralogical features that point to a past climate that was episodically favorable to liquid water (Figure 1a). These features — including valley networks [1], open- and closed-basin lakes [2], alluvial fans [3], shorelines [4], and alteration minerals such as phyllosilicates and sulfates [5] — suggest the existence of a hydrological cycle involving precipitation, runoff, and groundwater flow. Reconstructing the water distribution and hydrological dynamics of early Mars is essential to constrain past climate scenarios. We have developed a global hydrological model [6] for early Mars to simulate the distribution and dynamics of surface water under warm and wet conditions by exploring different Global Equivalent Layer (GEL) values and evaporation/precipitation schemes as functions of elevation or latitude. Here, we present the model applications and latest developments, including: (1) the comparison of model results from conceptual climate scenarios with observed valley networks, deltas, and lakes; (2) the investigation of transient effects and the formation of valleys from catastrophic outflow events; and (3) the coupling with a groundwater flow model to account for aquifer recharge and groundwater seepage.

Figure 1. Observed data (a) and model outputs at steady state with a GEL of 100 m (b–c) focused on the Gale Crater watershed (white star). These results are from a global-scale model [6]. (a) Digital Elevation Model from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) [7]. Blue lines represent valley networks [1]. White and red dots indicate open- and closed-basin lakes, respectively [2]. Orange triangles denote deltas [3]. (b) Distribution of surface water reservoirs (blue areas); the color bar shows water depth. (c) Streamflow along the simulated valley network; transparent sky blue areas indicate lake surfaces.

The surface hydrological model [6] simulates the steady-state distribution of water across the Martian surface by iteratively filling depressions and transferring excess water downstream. Water mass is conserved globally, and evaporated water is redistributed planet-wide as a conceptual form of precipitation, simulating a closed water cycle. Model outputs include the extent of surface water reservoirs (Figure 1b) and the overflow rates of depressions that exceed their storage capacity (Figure 1c). To assess model simulations, we compare simulated results with geomorphological data: the locations of lakes, valley networks, and deltas (Figure 1a). We developed quantitative indicators to evaluate the agreement between model outputs and observations, enabling the testing of different climate scenarios and GEL for their consistency with the preserved surface features. To further investigate landscape evolution, an erosion process was implemented to simulate catastrophic outflow events that may form large meander valleys. This addition allows us to study transient responses and long-term geomorphological impacts of such events.

While the surface model captures overland flow and lake formation, it does not account for water infiltration, subsurface storage, or groundwater discharge. To address this, we coupled a groundwater model [8] with the surface model. The coupled system evolves iteratively toward a steady-state distribution under constant climate forcing. We assess the effect of including groundwater processes on simulated surface water by comparing model results to observed geomorphological features. We also apply the coupled model to selected large watersheds derived from valley network catchments to estimate aquifer recharge rates required to sustain valley streamflows. Incorporating groundwater dynamics significantly improves the simulation of subsurface–surface water interactions and the representation of long-term water balance.

This work introduces an efficient framework for simulating early Mars hydrology at the planetary scale. By coupling surface and subsurface processes and comparing model outputs with geomorphological data, we provide new insights into the spatial and temporal distribution of water on early Mars and its implications for paleoclimate. Future work will focus on asynchronous coupling with a 3D Global Climate Model (GCM), enabling precipitation and temperature fields to evolve dynamically with the hydrological model. We also plan to explore transient simulations that account for episodic warming events and variable recharge scenarios.

References:

[1] Hynek et al.: Updated Global Map of Martian Valley Networks and Implications for Climate and Hydrologic Processes, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JE003548, 2010.

[2] Goudge et al.: Insights into Surface Runoff on Early Mars from Paleolake Basin Morphology and Stratigraphy, https://doi.org/10.1130/G37734.1, 2016.

[3] Di Achille and Hynek: Ancient Ocean on Mars Supported by Global Distribution of Deltas and Valleys, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo891, 2010.

[4] Sholes et al.: Where are Mars’ Hypothesized Ocean Shorelines? Large Lateral and Topographic Offsets Between Different Versions of Paleoshoreline Maps, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JE006486, 2021.

[5] Carter et al.: Widespread surface weathering on early Mars: A case for a warmer and635wetter climate, Icarus, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2014.11.011, 2015.

[6] Gauvain et al: A Global High-Resolution Hydrological Model to Study the Dynamics of Surface Liquid Water Reservoirs on Early Mars, Geoscientific Model Development, EGU, submited.

[7] Smith et al.: Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter:Experiment summary after the first year of global mapping of Mars, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, https://doi.org/10.1029/2000JE001364, 2001.

[8] Langevin et al.: Documentation for the MODFLOW 6 Groundwater Flow Model: U.S. Geological Survey Techniques and Methods, https://doi.org/10.3133/tm6A55, 2017.

How to cite: Gauvain, A., Forget, F., Turbet, M., and Clément, J.-B.: Constraining Early Mars Climate Through Coupled Hydrological Modeling and Comparison with Geomorphological Evidence, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1263, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1263, 2025.