Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

TP1

This session is now established for 10 years, and typically attracts a good amount of contributions reflecting the diversity of missions and science questions related to the solid portions of, covering the broad scope of current research.

Session assets

Introduction

The Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS; Thomas et al., 2017) has been acquiring 4 m/pixel images of the martian surface since 2018, building a database of over 38,000 images in up to four spectral bands across the planet. CaSSIS NIR-PAN-BLU (NPB) and HiRISE IR-RED-BLUE (IRB) images reveal conspicuous, red-toned outcrops (RTO) at a range of scales that are distributed across the southern highlands. While visually striking, the composition, distribution, and origins of these outcrops remain unclear. Here, we present a global analysis of RTOs aimed at resolving this.

Methods

To investigate the RTO, we manually identified a selection of ~30 examples of RTO covering a range of sizes, morphologies, textures, colours, and lighting geometries in CaSSIS NPB images, and used these examples as a training dataset for a convolutional neural network (CNN), which is able to detect occurrences of RTO similar to those in the training dataset (see techniques in Bickel et al., 2024 and references therein).

The CNN assessed all >38,000 images in the CaSSIS database (as at 28/02/2024), and produced an output of 2232 detections at >60% CNN confidence level. These outputs were manually sorted to remove false positives and to assess RTO morphology/texture. True positive RTOs, as well as those from the training dataset, were compared with CRISM footprints, and those CRISM MTRDR cubes that overlapped were analysed following the standard ratioing method (e.g. McGuire et al., 2009; Murchie et al., 2007).

Results

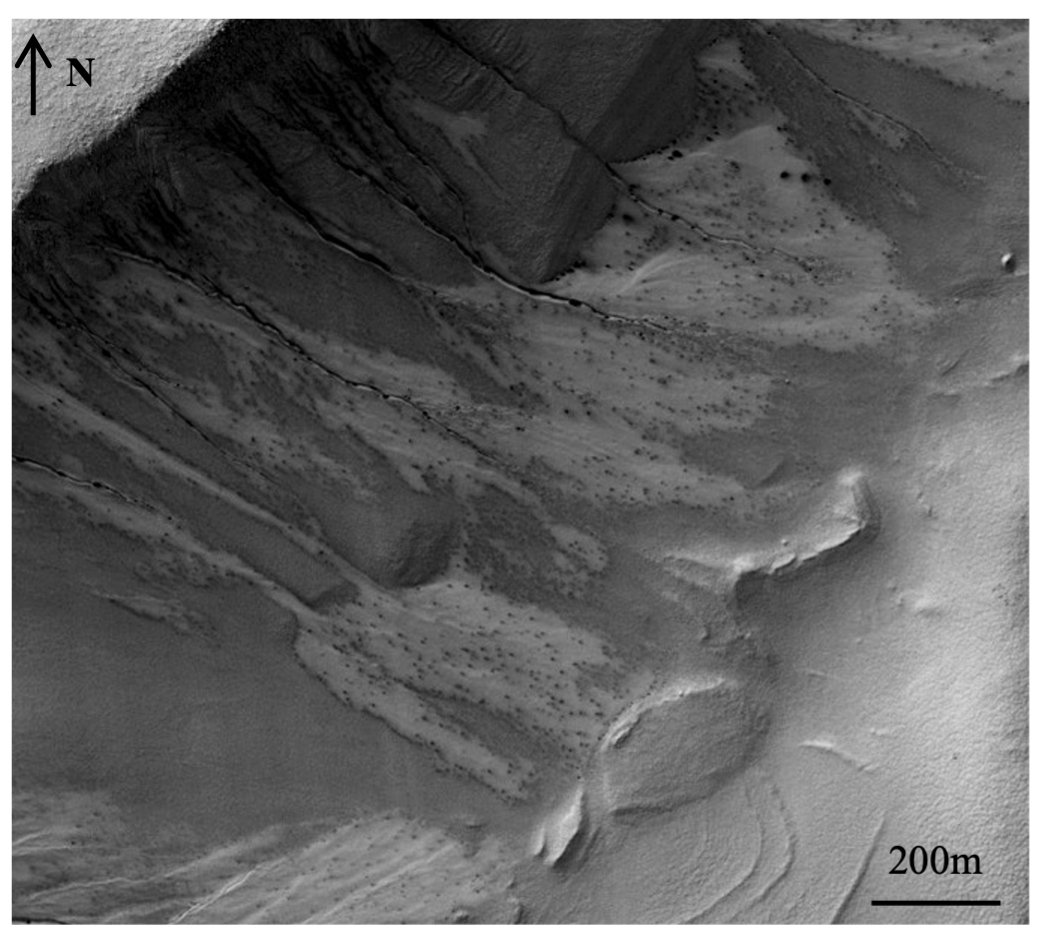

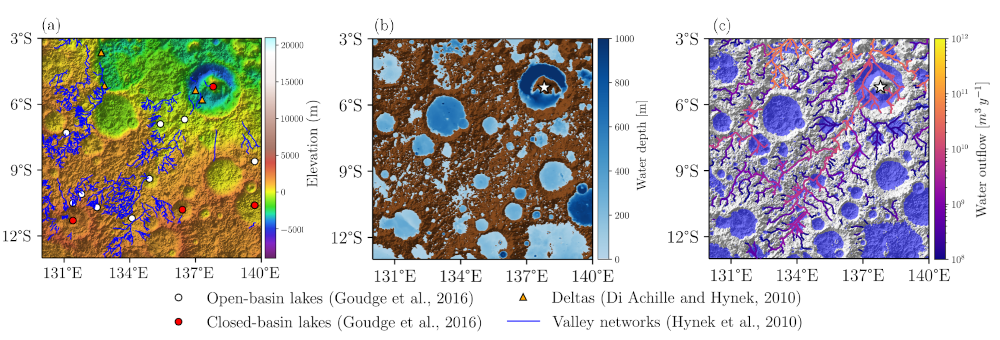

We observe a total of 923 “true positive” RTO CaSSIS detections (e.g. Figure 1). RTOs are most common in the areas north of the Hellas and Argyre basins, in lower elevation regions of eastern Valles Marineris, and in the Nili Fossae region. These usually crop out in the ejecta of large (>10 km) craters in these areas but can also be observed in the walls of craters and on relatively flat-lying terrain. Most RTOs are associated with Noachian-aged terrains with 76% occurring within Noachian Units (Tanaka et al., 2014), 12% in Hesperian Units, 4% in Amazonian Units, and 8% in Hesperian/Amazonian Impact Units.

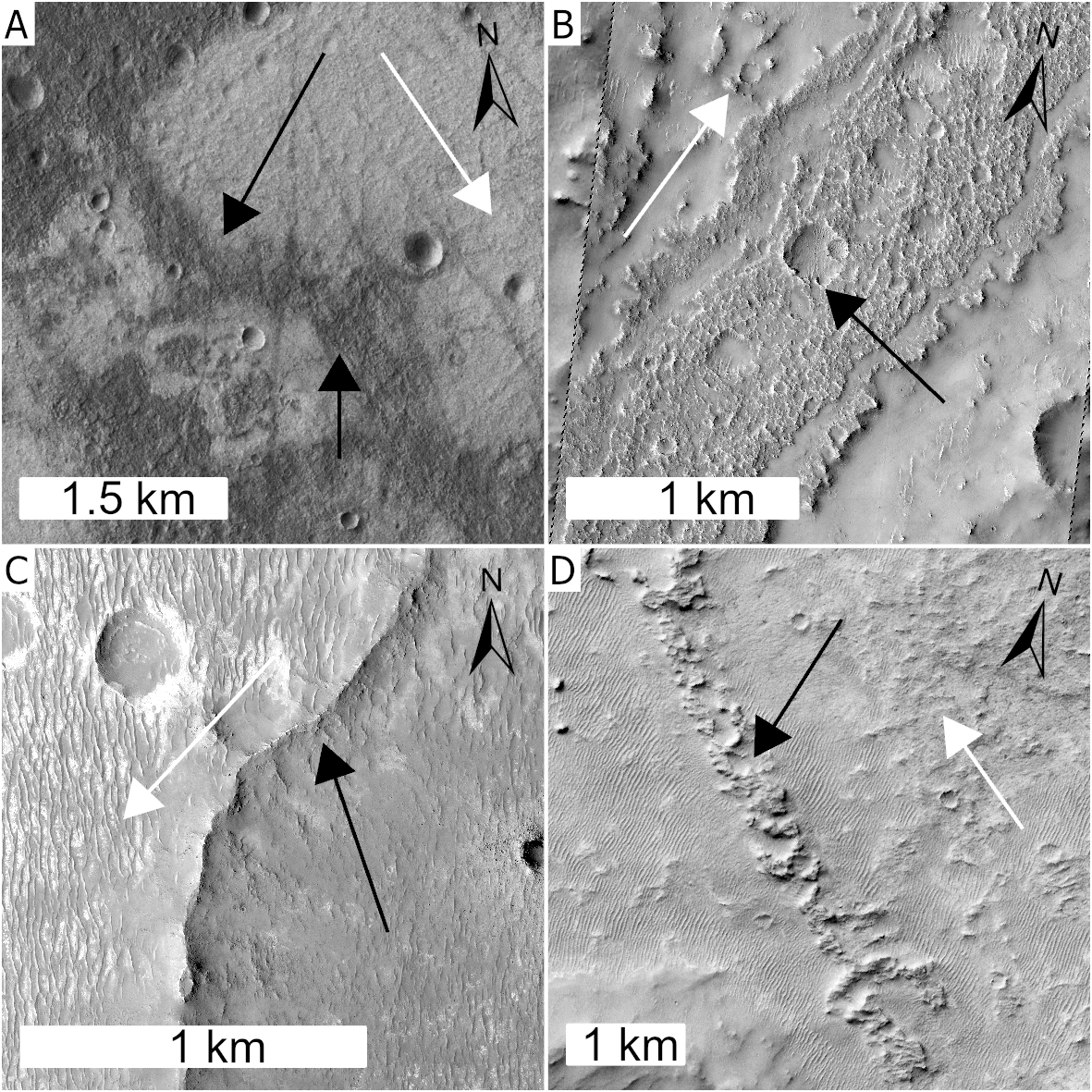

RTOs typically possess a blocky, massive appearance (Figure 1a), and occur as both discrete outcrops with well-defined margins (Figure 1b), interpreted as ejecta blocks, or as diffuse deposits (Figure 1c), interpreted as intermixing with other components within ejecta blankets.

CRISM spectra from RTOs reveal a consistent and broad, yet extremely weak and slightly long-shifted 1.25 μm absorption feature, consistent with partial transformation of Fe-plagioclase to maskelynite, a diaplectic amorphous glass associated with shock metamorphism from hypervelocity impact events (e.g. Jaret et al., 2015; Spudis et al., 1984).

Figure 1: False-color examples of Red-Toned Outcrops (RTOs) from across the Hellas region. a) Large blocky RTO in Terby Crater (CaSSIS NPB); b) Discrete fractured RTO north of Hellas (HiRISE IRB); c) Large diffuse RTO with some sharp boundaries NW of Hellas (CaSSIS NPB); d) RTO under younger dark material NE of Hellas (CaSSIS NPB).

Discussion

We infer RTOs to be the products of large basin-forming impacts, with their current distribution shaped by subsequent impact gardening. Their occurrence surrounding Hellas and Argyre suggests that these units are part of the original basin ejecta fields and therefore, at least in the case of Hellas, predate the Noachian. In these regions, RTOs likely derive from Fe-plagioclase-bearing massifs uplifted from depth during the impact events, now observed as degraded massifs along the basin rims (Phillips et al., 2022; Phillips and Viviano, 2025).

RTO exposures are commonly found within ejecta in impact-modified terrains superposed on the Hellas and Argyre ejecta blankets. The absence of similar features in Noachian-aged terrains outside of these ejecta fields suggests that large basin-forming impacts are a pre-requisite to exhume deeply buried plagioclase material, and that subsequent impact gardening of basin ejecta is a primary mechanism for their exposure.

Collectively, the observed distribution, morphology, and mineralogy of RTOs point to the presence of a plagioclase-rich lower crustal component that was widespread in the Pre-Noachian martian crust, likely explaining the lower-than-expected observed density of the martian crust (Knapmeyer-Endrun et al., 2021; Bouley et al., 2020; Baratoux et al., 2014). The evidence indicates that this plagioclase-rich material underwent shock metamorphism, excavation, and emplacement within the ejecta of early basin-forming events, providing a unique window into the composition and modification history of Mars’ ancient crust.

References

- Baratoux, D., et al. (2014) Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, vol. 119, no. 7, pp. 1707–1727

- Bickel, V. T., et al. (2024) Scientific Data, vol. 11, no. 1, p. 845

- Bouley, S., et al. (2020) Nature Geoscience, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 105–109

- Jaret, S. J., et al (2015) Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, vol. 120, no. 3, pp. 570–587

- Knapmeyer-Endrun, B., et al. (2021) Science, vol. 373, no. 6553, pp. 438–443

- McGuire, P. C., et al. (2009) Planetary and Space Science, vol. 57, no. 7, pp. 809–815

- Murchie, S., et al. (2007) Journal of Geophysical Research E: Planets, vol. 112, no. 5, pp. 1–57

- Phillips, M. S. and Viviano, C. E. (2025) LPSC 56, Houston, Texas, abs#1653

- Phillips, M. S., et al. (2022) Geology, vol. 50, no. 10, pp. 1182–1186

- Spudis, P. D., et al. (1984) Journal of Geophysical Research, vol. 89

- Thomas, N., et al. (2017) Space Science Reviews, vol. 212, no. 3–4, pp. 1897–1944

How to cite: McNeil, J., Grindrod, P., Tornabene, L., Bickel, V., Stabbins, R., and Cuadros, J.: Seeing Red: Shocked Plagioclase as Pre-Noachian Stratigraphic Tracers, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-617, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-617, 2025.

The Mawrth Vallis region of Mars features abundant phyllosilicate outcrops as well as smaller areas where sulfates are present. This study evaluates field sites where phyllosilicates and sulfates co-occur to assist in constraining the ancient geochemical environments on Mars. Mineral transitions at Mawrth Vallis indicate changing geochemical conditions over time - from the lower Fe-rich smectite horizon about 200 meters thick to thinner units of sulfates, Al-phyllosilicates including halloysite in some regions, then Si-rich phases at the top of the profile [1] (Fig. 1a-c). Smectites form through wet/dry cycling in generally arid environments, while halloysite requires more humid conditions. Ca-sulfates and Al-clays represent a decrease in pH from the environment supporting formation of Fe/Mg-smectite, and the jarosite outcrops indicate an even lower pH. Sulfuric gases released from Syrtis may have produced sulfates in the groundwater [2] that flowed downhill from Meridiani towards Mawrth Vallis (Fig. 1d). This could have produced acidic brines that altered the expansive Fe/Mg-smectites at Mawrth Vallis and formed pockets of sulfates.

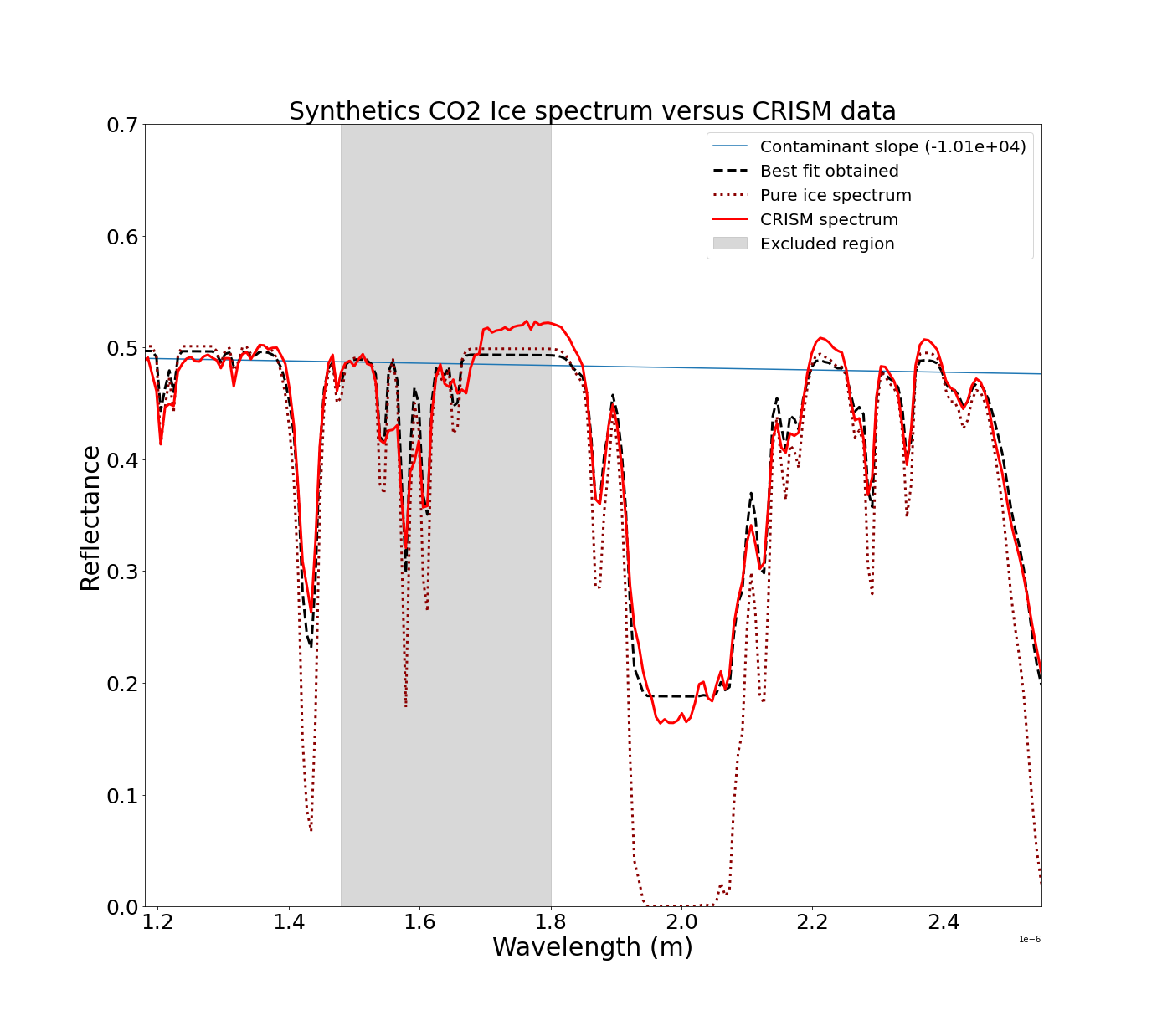

Specific phyllosilicate and sulfate minerals are mapped using vibrational bands in CRISM images (Fig. 1a). Spectral features in the region ~1.4-2.6 µm are most useful for identifying and characterizing these minerals, including the H2O combination band near 1.91-1.92 µm. The Fe-rich smectite outcrops also exhibit Fe-OH bands near 1.42 and 2.29-2.30 µm. The Al-smectite units include Al-OH bands at 1.41-1.42 and 2.20-2.21 µm, while small locations containing halloysite/kaolinite and alunite have additional bands near 1.39-1.47, 1.75, 2.17, and 2.32 µm (Fig. 2). Areas containing jarosite have spectral bands near 1.47, 1.85, 2.22, and 2.26 µm (Fig. 3). Sites including hydrated sulfates include a drop in reflectance near 2.4-2.5 µm and Ca sulfates have a band near 1.75-1.78 µm.

Phyllosilicate - sulfate assemblages were investigated at field sites to assist in constraining the environments where these minerals form. The Painted Desert in Arizona features expansive outcrops of clay-bearing horizons (Fig. 4a), similar to Mawrth Vallis. Coordinated analyses of spectra from the field, lab, and aerial instruments of the light-toned and reddish horizons show the presence of clays and carbonates [3] (Fig. 4b-d). Sulfates are present in regions with polygonally-cracked surfaces where combinations of gypsum, jarosite, and montmorillonite are observed [4] (Fig 4ef). The south sulfur bank inside the Kilauea caldera (Fig. 5) contains a mixture of nontronite, saponite, montmorillonite, opal-A, gypsum, jarosite, and ferrihydrite due to hydrothermal alteration of ash and basalt from volcanic gases [5]. Lighter-toned outcrops are dominated by opal with some gypsum, saponite and jarosite (Fig. 5d), while the darker orange-tan layers include nontronite, ferrihydrite, and jarosite in addition to opal and gypsum (Fig. 5e). Analogs from the rainy Waimea Canyon region of Kauai include goethite, halloysite, ferrihydrite, and allophane in altered rinds on the rocks (Fig. 6). Additional sites altered under lower pH conditions contain hematite and jarosite [6].

Pedogenic alteration at the Painted Desert produced wide horizons of clay-bearing units interspersed with units of iron oxides/hydroxides and carbonates. Sulfates are observed together with phyllosilicates in regions with polygonally-cracked terrain. Jarosite and gypsum are present in a hydrothermal setting at Kilauea, while halloysite and goethite or jarosite and hematite are observed in the rainy and highly leached environment of Kauai. Observations of alteration minerals at these field sites suggest the Mawrth Vallis region of Mars experienced a largely arid environment with wet/dry cycling to produce the thick smectite profiles, with short-term periods of acidic fluids to form sulfates and strong leaching to form halloysite. Allophane likely formed on Mars when water was less abundant or colder [7].

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful for support from NASA MDAP # 80NSSC19K1230 and NASA SSW #80NSSC23K0032.

References: [1] Bishop et al. (2020) Multiple mineral horizons in layered outcrops at Mawrth Vallis, Mars, signify changing geochemical environments on early Mars, Icarus, 341, 113634. [2] Moore & Szynkiewicz (2023) Aqueous sulfate contributions in terrestrial basaltic catchments: Implications for understanding sulfate sources and transport in Meridiani Planum, Mars, Icarus, 391, 115342. [3] McKeown et al. (2009) Coordinated lab, field, and aerial study of the Painted Desert, AZ, as a potential analog site for phyllosilicates at Mawrth Vallis, Mars, 40th LPSC, #2509. [4] Perrin et al. (2018) Mars evaporite analog site containing jarosite and gypsum at Sulfate Hill, Painted Desert, AZ, 49th LPSC, #1801. [5] Bishop et al. (2024) Solfataric alteration at the South Sulfur Bank, Kilauea, Hawaii, as a mechanism for formation of sulfates, phyllosilicates, and silica on Mars American Miner., 109, 1871–1887. [6] Gruendler et al. (2023) Characterizing Altered Volcanic Rocks from Waimea Canyon, Kauai, 54th LPSC, #1892. [7] Bishop et al. (2018) Surface clay formation during short-term warmer and wetter conditions on a largely cold ancient Mars, Nature Astronomy, 2, 206-213.

Figures:

Fig. 1 a-c) Alteration at Mawrth Vallis, Mars [1]. a) CRISM spectra of 5 distinct units. b) Diagram of altered stratigraphy. c) View of CRISM over HRSC. d) Potential formation mechanism for sulfate formation in groundwater at Mawrth Vallis, after [2].

Fig. 2 a) HRSC view of light-toned phyllosilicate-rich units. b) CRISM image FRT0000B141. c) Mineral parameter maps for Fe-smectite, halloysite, Al-smectite. d) CRISM spectra of selected outcrops compared to spectra of minerals.

Fig. 3 a) HRSC view of light-toned phyllosilicate-rich units. b) CRISM image FRT0000A425 with region containing jarosite marked by blue oval. c) Mineral parameter maps including jarosite. d) CRISM spectra of selected outcrops compared to spectra of minerals.

Fig. 4 Painted Desert, Arizona. a) Phyllosilicate-rich horizons. b-c) Close-up views of changing mineralogy. d) Comparison of HyMap aerial spectra with field and lab spectra. e) Gypsum and jarosite outcrops under polygonally-cracked terrain. f) Spectra of Painted Desert materials and lab mixtures compared to CRISM spectrum.

Fig. 5 Kilauea south sulfur bank, Hawaii. a) LG with field spectrometer. b) View of light-toned material. c) JLB sampling orange layered material. d-e) VNIR spectra of light-toned material, orange layers, and minerals.

Fig. 6 a) Waimea Canyon, Kauai. b-c) Close-up views of altered rocks. d) Spectra of selected samples compared to spectra of minerals.

How to cite: Bishop, J., Gruendler, L., Gruendler, K., Parente, M., Gross, C., Saranath, A., Itoh, Y., Gruendler, M., McKeown, N., and Murchie, S.: Constraining the Ancient Geochemical Environments that formed the Complex Phyllosilicate and Sulfate Assemblages at Mawrth Vallis Through Comparison with Field Sites, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1957, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1957, 2025.

The study of Martian mineralogy provides valuable insights into its geological history and environmental conditions over time. One significant aspect of Martian mineralogy is the presence of Fe/Mg-phyllosilicates, also known as clay minerals. These phyllosilicates are important indicators of past aqueous activity on Mars, suggesting the presence of water in its early history. The formation of Fe/Mg-phyllosilicates typically occurs in environments with moderate to low temperatures and near-neutral pH conditions, where water interacts with volcanic rocks or crustal materials containing iron and magnesium. Phyllosilicates make up the majority of aqueously altered minerals on Mars and are widespread on its surface, preferably in ancient Noachian/Hesperian terrains.

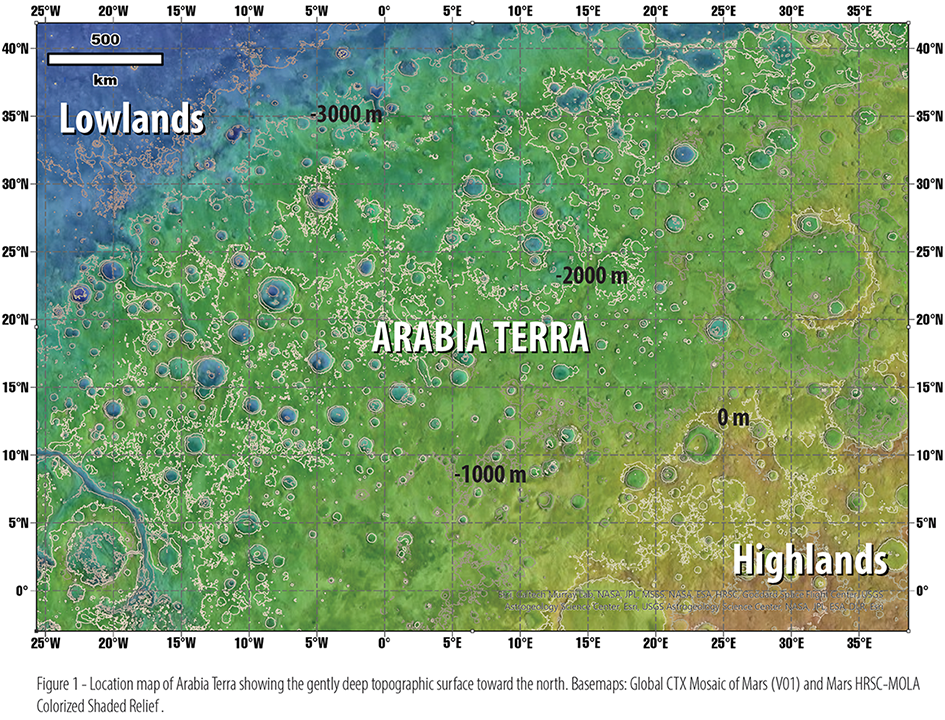

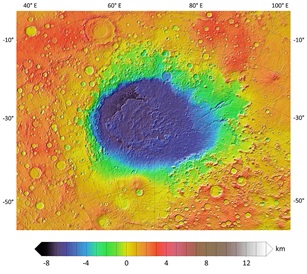

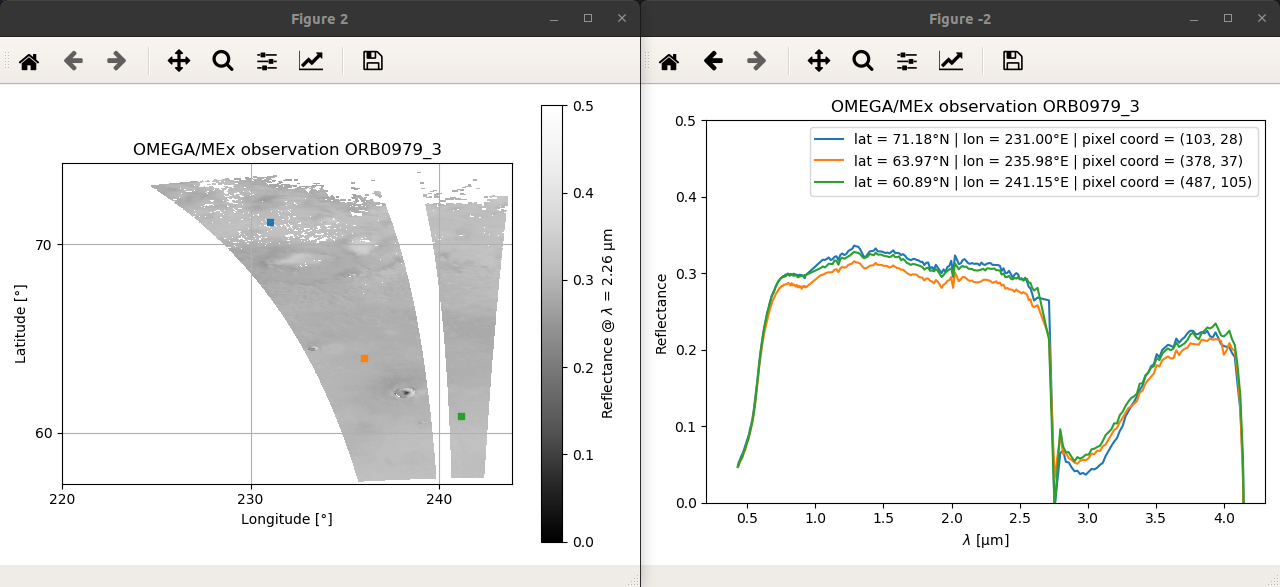

Significant amounts of this mineral type have been detected from orbital measurements by the Mars Express/OMEGA and MRO/CRISM spectrometers and are recorded in the Mars Orbital Catalog of Aqueous Alteration Signatures (MOCAAS) [1]. This work concentrates on the substantial Fe/Mg-phyllosilicate deposits that were detected northwest of Argyre Planitia, one of the large impact basins in the ancient terrain of the southern hemisphere of Mars. Despite the wide-spread presence of alteration minerals in this region, no detailed studies have ever been conducted to characterize their geology and chronology.

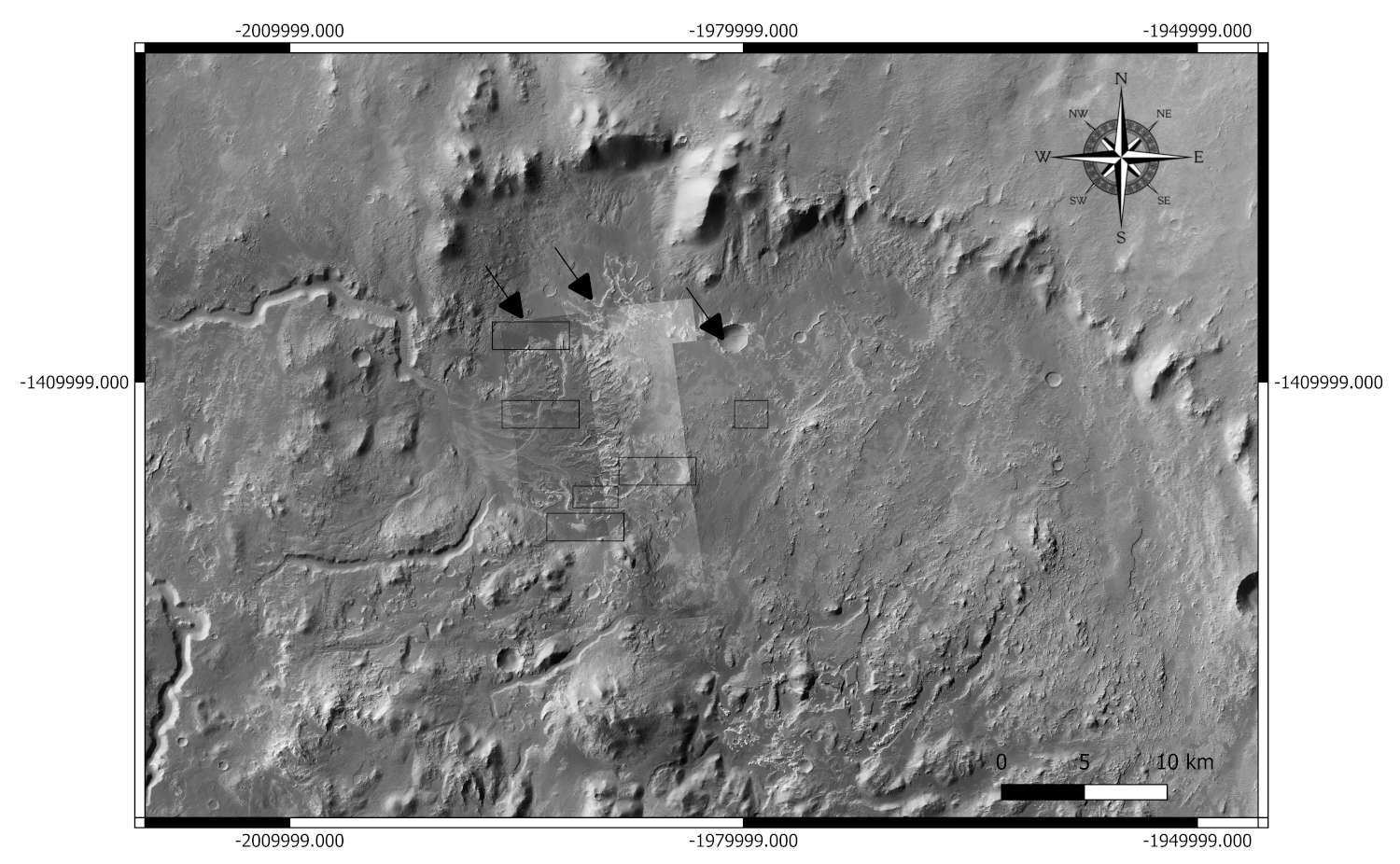

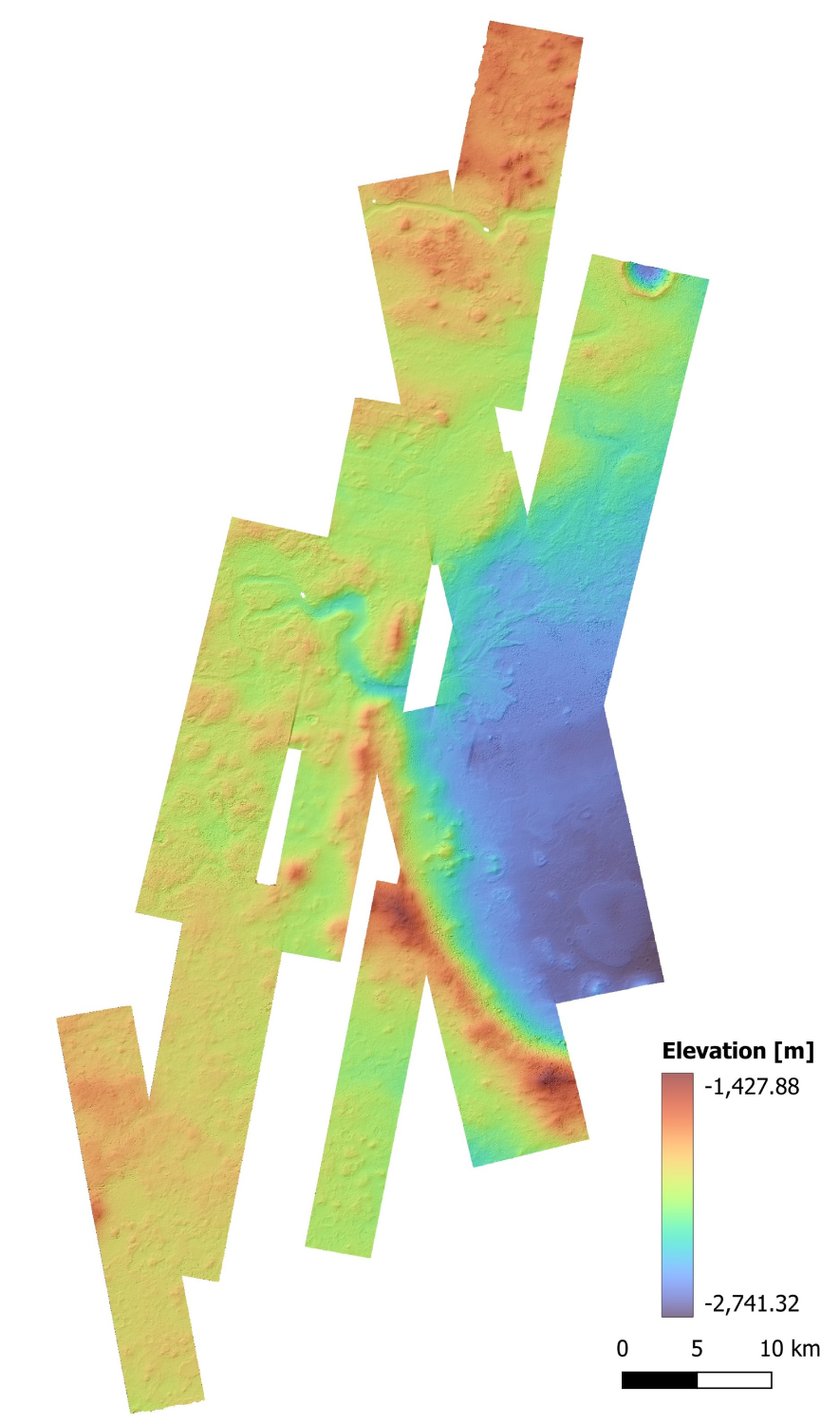

We investigated the substantial Fe/Mg-phyllosilicate deposits that were detected northwest on Argyre Planitia to shed light on to what extent these hydrated minerals correlate with deposits and structures that were formed by the formation of the Argyre basin, such as impact-induced hydrothermal alteration processes and impact tectonics.

We used remote sensing data (HRSC [2], CTX [3], THEMIS [4], HiRISE [5], MGS MOLA - MEX HRSC Blended DEM Global [6], CaSSIS [7]) to produce a photogeological map with a mapping scale of 1:100,000 and boundaries of 41.5°S to 36.5°S and 298°E to 304°E. The mapping was accomplished on CTX whereas the other dataset were used to validate different surface units. In particular, we used multispectral colour data from HRSC and CaSSIS to discriminate candidate units in terms of their mineralogical composition.

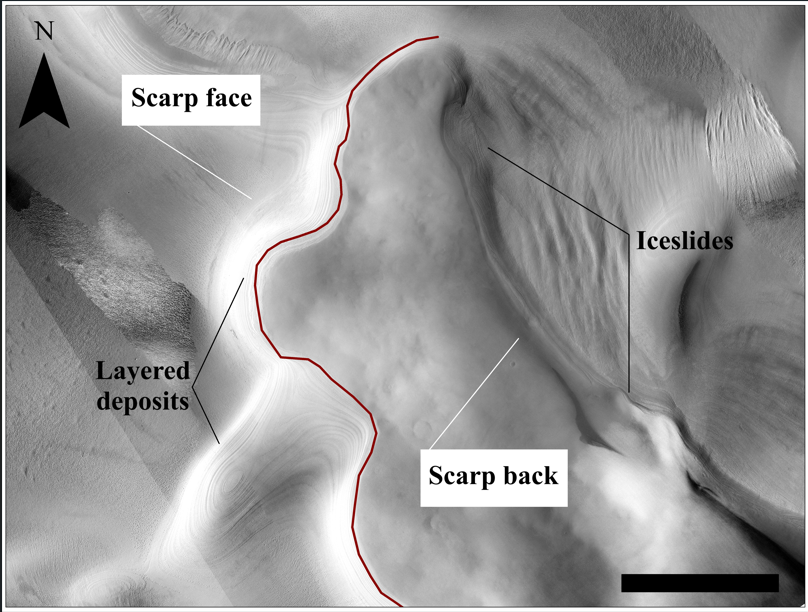

Our region of interest features widespread fractured units that are embayed between two presumably tectonic, scarp-bounded blocks with an elongation approximately concentric around Argye, suggesting a impact-controlled structural history. The unit “fractures_light_tones_plains” and “smooth_light_toned_plain” are considered the main clay-bearing units of interest due to their spatial correspondence with the areas where MOCAAS detected Fe/Mg-phyllosilicates. The region also displays abundant fractures forming polygonal ground, a characteristic that is typically associated with phyllosilicates elsewhere on Mars.

References

[1] Carter, J., Riu, L., Poulet, F., Bibring, J.-P., Langevin, Y., Gondet, B., 2023. A Mars orbital catalog of aqueous alteration signatures (MOCAAS). Icarus 389, 115164, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2022.115164.

[2] Jaumann, R., Neukum, G., Behnke, T., Duxbury, T.C., Eichentopf, K., Flohrer, J., Gasselt, S.v., Giese, B., Gwinner, K., Hauber, E., Hoffmann, H., Hoffmeister, A., Köhler, U., Matz, K.-D., McCord, T.B., Mertens, V., Oberst, J., Pischel, R., Reiss, D., Ress, E., Roatsch, T., Saiger, P., Saiger, F., Scholten, F., Schwarz, G., Stephan, K., Wählisch, M., the HRSC Co-Investigator Team, 2007. The high-resolution stereo camera (HRSC) experiment on Mars Express: Instrument aspects and experiment conduct from interplanetary cruise through the nominal mission. Planetary and Space Science 55, 928-952[3] Malin, M. C., Bell, J. F., Cantor, B. A., Caplinger, M. A., Calvin, W. M., Clancy, R. T., et al. (2007). Context camera investigation on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Journal of Geophysical Research, 112, E05S04. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JE002808.

[3] Malin, M. C., Bell, J. F., Cantor, B. A., Caplinger, M. A., Calvin, W. M., Clancy, R. T., et al. (2007). Context camera investigation on board the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Journal of Geophysical Research, 112, E05S04. https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JE002808

[4] Christensen, P.R., Jakosky, B.M., Kieffer, H.H. et al. The Thermal Emission Imaging System (THEMIS) for the Mars 2001 Odyssey Mission. Space Science Reviews 110, 85–130 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SPAC.0000021008.16305.94.

[5] McEwen, A. S., Eliason, E. M., Bergstrom, J. W., Bridges, N. T., Hansen, C. J., Delamere, W. A., et al. (2007). Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE). Journal of Geophysical Research, 112(E5). https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JE002605.

[6] Smith, D., Zuber, M., Frey, H., Garvin, J., Head, J., Muhleman, D., . . . Banerdt, W. (2001). Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter: Experiment summary after the first year of global mapping of Mars. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 106(E10), 23689-23722. doi:10.1029/2000JE001364.

[7] Thomas, N., Cremonese, G., Ziethe, R. et al. The Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS) for the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter. Space Sci Rev 212, 1897–1944 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-017-0421-1.

How to cite: Da Silva Encarnacao, M., Tirsch, D., Hauber, E., Rangarajan, V., Machado, P., and Peixinho, N.: Mapping of phyllosilicates NW of Argyre basin (Mars) with Mars Express/HRSC colour data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1729, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1729, 2025.

Introduction:

Iron plays a pivotal role in shaping Mars’ surface processes, influencing its climate evolution, and affecting its potential for habitability. Over the past decade, data from Mars exploration missions have significantly deepened our understanding of iron geochemical cycling -- the set of processes through which iron transitions between different oxidation states and mineral forms within the Martian surface environment. These transformations are closely linked to Martian hydrological activity, atmospheric changes, and redox conditions that may have supported life. This review synthesizes key advances in our knowledge of iron cycling on Mars from recent years. It examines the primary sources and mineral forms of iron, traces the temporal evolution of iron cycling across geological epochs, explores its environmental and climatic implications, and reviews mechanistic insights gained from experimental and modeling studies. The paper also discusses unresolved scientific debates and methodological challenges, providing perspectives to guide future study.

Sources and forms of Fe on Mars

Iron inventory on Mars primarily originates from mafic and ultramafic igneous rocks formed through planetary differentiation and volcanic activity. Over time, these iron-bearing silicates underwent aqueous alteration, giving rise to a diverse suite of secondary minerals. These include iron oxides (e.g., hematite, magnetite), hydroxides (e.g., goethite, ferrihydrite), sulfates (e.g., jarosite), carbonates (e.g., siderite), and iron-rich phyllosilicates (e.g., nontronite) [1,2]. Notable new discoveries from the rover missions include siderite-rich layers in Gale Crater, suggesting CO₂ sequestration in ancient Martian lakes [3] and at Jezero Crater, Perseverance identified coarse-grained olivine-rich igneous rocks and serpentinized fragments, indicative of hydrothermal activity [4]. Furthermore, spectral analyses now suggest that Martian dust is dominated not by crystalline hematite, but by ferrihydrite, an amorphous iron oxyhydroxide typically formed under low-temperature aqueous conditions [2].

Temporal evolution of Fe cycling

Iron cycling on Mars closely mirrors the planetary transition from early wet or icy conditions to the cold, arid environment observed today. During the Noachian period (4.1-3.7 Ga), iron was likely highly mobile in the form of Fe²⁺ within neutral to mildly acidic aqueous environments. Evidence from Gale Crater suggests the presence of redox-stratified lake systems, characterized by magnetite and ferrous phyllosilicates at depth, with more oxidized iron phases near the surface [5]. Ferrihydrite-rich sediments may also have formed under these conditions. In the Hesperian epoch (~3.7-3.0 Ga), increasingly oxidizing and acidic conditions favored the formation of iron sulfates, such as jarosite. The detection of high-Mn oxides by the Curiosity rover has been interpreted as evidence for transiently oxygen-rich episodes[6], though alternative oxidants, such as chlorates or UV-driven photochemical processes, remain plausible [7]. During the Amazonian period (~3.0 Ga to present), extreme cold and aridity severely limited aqueous alteration. Iron cycling during this time has been dominated by the oxidation of surface-exposed Fe²⁺ minerals and the wind-driven redistribution of iron-rich dust.

Climatic and habitability implications

Iron minerals function as valuable environmental proxies on Mars. For example, ferrihydrite is indicative of cold, aqueous conditions, while jarosite and other sulfates point to acidic, evaporative environments. The occurrence of siderite implies near-neutral pH and elevated CO₂ levels, suggesting a more temperate early climate [3]. Beyond environmental reconstruction, iron redox cycling may have supported microbial metabolisms. Nitrate-dependent Fe²⁺ oxidation has been proposed as an energetically favorable pathway in early Martian lakes, which likely contained both dissolved Fe²⁺ and nitrate [8]. Moreover, oxidized iron minerals may have served as long-term sinks for oxygen, helping to buffer the planetary atmospheric composition and influence climate evolution. In the present day, iron-bearing dust continues to affect Mars energy balance by modulating solar radiation and atmospheric dynamics.

Future directions

Iron cycling on Mars has not only recorded environmental transitions but has also actively shaped them. Processes such as serpentinization likely contributed to abiotic hydrogen production and may be linked to episodic methane detections. At the same time, extensive Fe oxidation may have consumed significant amounts of atmospheric O₂, hindering its long-term accumulation. Upcoming missions, including Mars sample return, will enable detailed laboratory analyses of iron speciation and isotopic composition, including isotopic signatures of other elements, critical for constraining the timing of redox transitions and evaluating potential biosignatures. Key open questions remain: When and how did the Fe oxidation occur on Mars? Did Mars undergo a global oxidation event? How deeply did oxidation penetrate the crust? Answering these questions will require integrated approaches that combine planetary missions, laboratory experiments, and advanced geochemical modeling.

Acknowledgements: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42441803, 4237304).

References

[1] Fraeman, A. A. et al. (2020). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 125, e2020JE006527.

[2] Valantinas, A. et al. (2025). Nat. Commun., 16, 1712.

[3] Tutolo, B. M. et al. (2025). Science, 370, 270-274.

[4] Farley, K. A. et al. (2022). Science, 377, 1321-1327.

[5] Hurowitz, J. A. et al. (2017). Science, 356, eaah6849.

[6] Lanza, N. L. et al. (2016). Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 7398-7407.

[7] Mitra, K. et al. (2022). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 127, e2021JE007067.

[8] Bryce, C. et al. (2018). Front. Microbiol., 9, 513.

How to cite: Zhao, Y.: Iron Geochemical Cycling on Mars: A Temporal and Planetary Perspective, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1488, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1488, 2025.

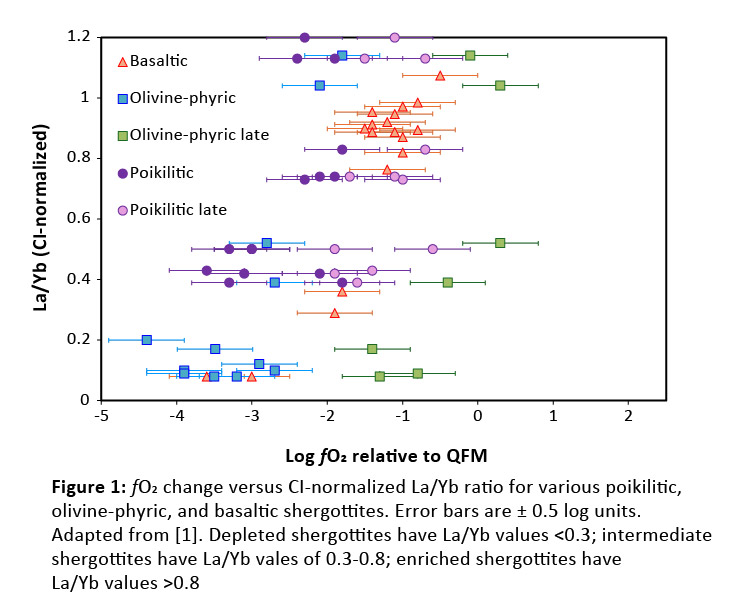

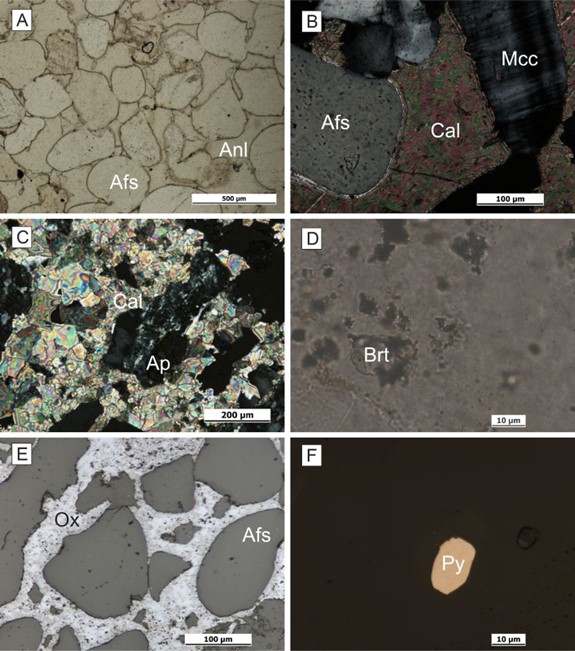

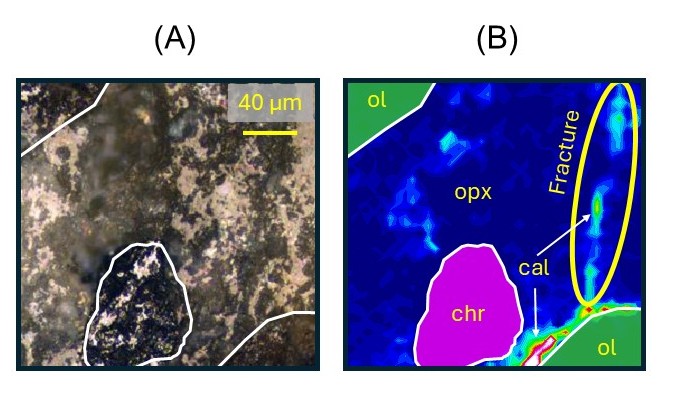

Introduction: Martian meteorites are currently the only samples on Earth available to study Mars. These samples comprise mainly (>80% by number) shergottite-type rocks, which are basaltic to lherzolitic [1]. Shergottites provide valuable information regarding the conditions of the martian interior, including its chemical composition and redox state. The redox state of shergottites of various petrologic types has been estimated (Fig. 1), and there appears to be a correlation between oxidation state and relative enrichment/depletion of incompatible trace elements (ITEs), with rocks that are enriched in ITEs also being more oxidized. An additional observation is that shergottites undergo extensive oxidation during their formation [2-4], with an increase in fO2 of 1-3 log units. Auto-oxidation can increase fO2 by a maximum of ~0.5 log units [3, 5] and thus cannot solely explain this change. Degassing of volatiles had been suggested as an alternative mechanism to oxidize these rocks [2-6]. Recent studies on the solubility of C, S, and H species in martian compositions [7-12], have allowed for Mars-appropriate degassing models to be developed, like Magma and Gas Equilibrium Calculation (MAGEC) [13]. MAGEC allows a user to specify the melt composition, pressure, temperature, and starting fO2 and calculates the proportion of volatile species that would exsolve from the melt, and the fO2 of the remaining melt. This study uses the program MAGEC to evaluate the effect of volatile degassing on the redox evolution of shergottites.

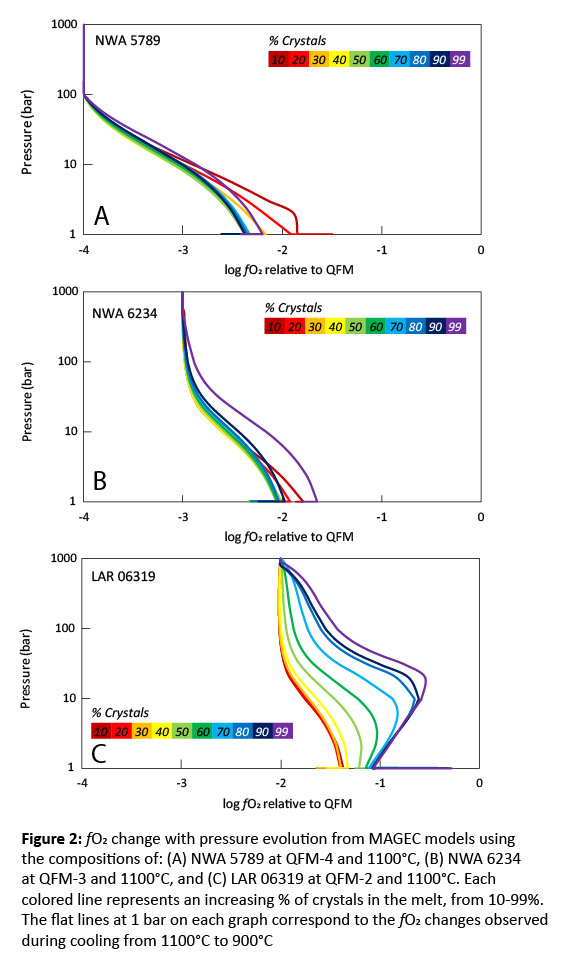

Methods: Various shergottite compositions were tested to capture the diversity within the group. The bulk compositions of olivine-phyric shergottites Northwest Africa (NWA) 5789 [14], NWA 6234 [15], and Larkman Nunatak (LAR) 06319 [16] were used, as these samples represent a mantle melt or closely approximate one, and thus, serve as representations of the martian interior. Additionally, the parental melt compositions of poikilitic shergottites NWA 7755, NWA 10169, NWA 11065, and Allan Hills (ALHA) 77005, estimated from their melt inclusions [6, 17], were used. Poikilitic shergottites were included in this study as they display some of the largest fO2 variations. To evaluate how changing melt composition can affect volatile degassing, all compositions were crystallized at 1 kbar at an fO2 of QFM-4, QFM-3, or QFM-2, using rhyolite-MELTS [18, 19]. The melt composition was recorded for every 10% of crystals formed, from 10%-99% crystals. Degassing models were run for every 10% increase in crystals/decrease in melt, with degassing from decompression occurring from 1000-1 bar at a temperature of 1100°C, 1050°C, 1000°C, or 950°C, and degassing from cooling occurring at 1 bar from the initial temperature down to 900°C. These models were run at an fO2 of QFM-4, QFM-3, or QFM-2, with 0.3 wt.% H2O, 0.08 wt.% CO2, and 0.5 wt.% S added. The volatile abundances used in this study are based on H, C, and S abundances estimated for the martian mantle and crust [7, 11, 20-24].

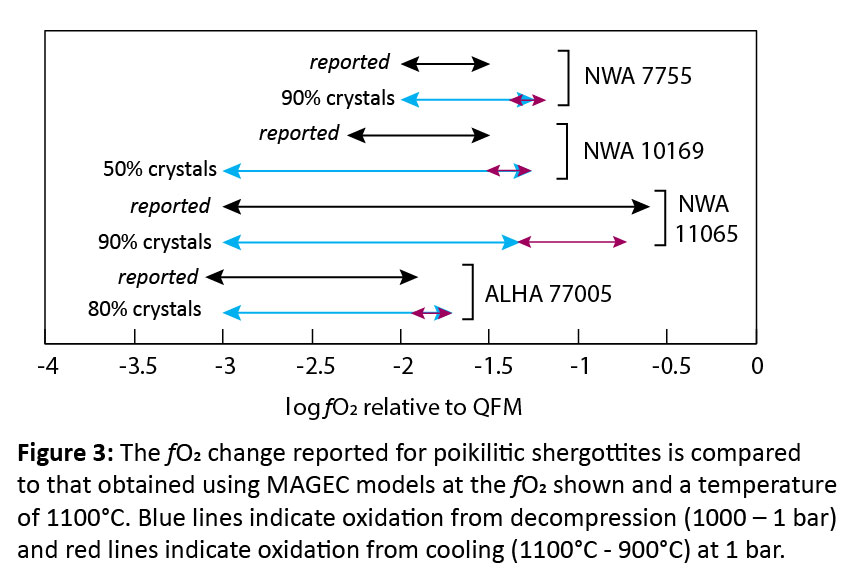

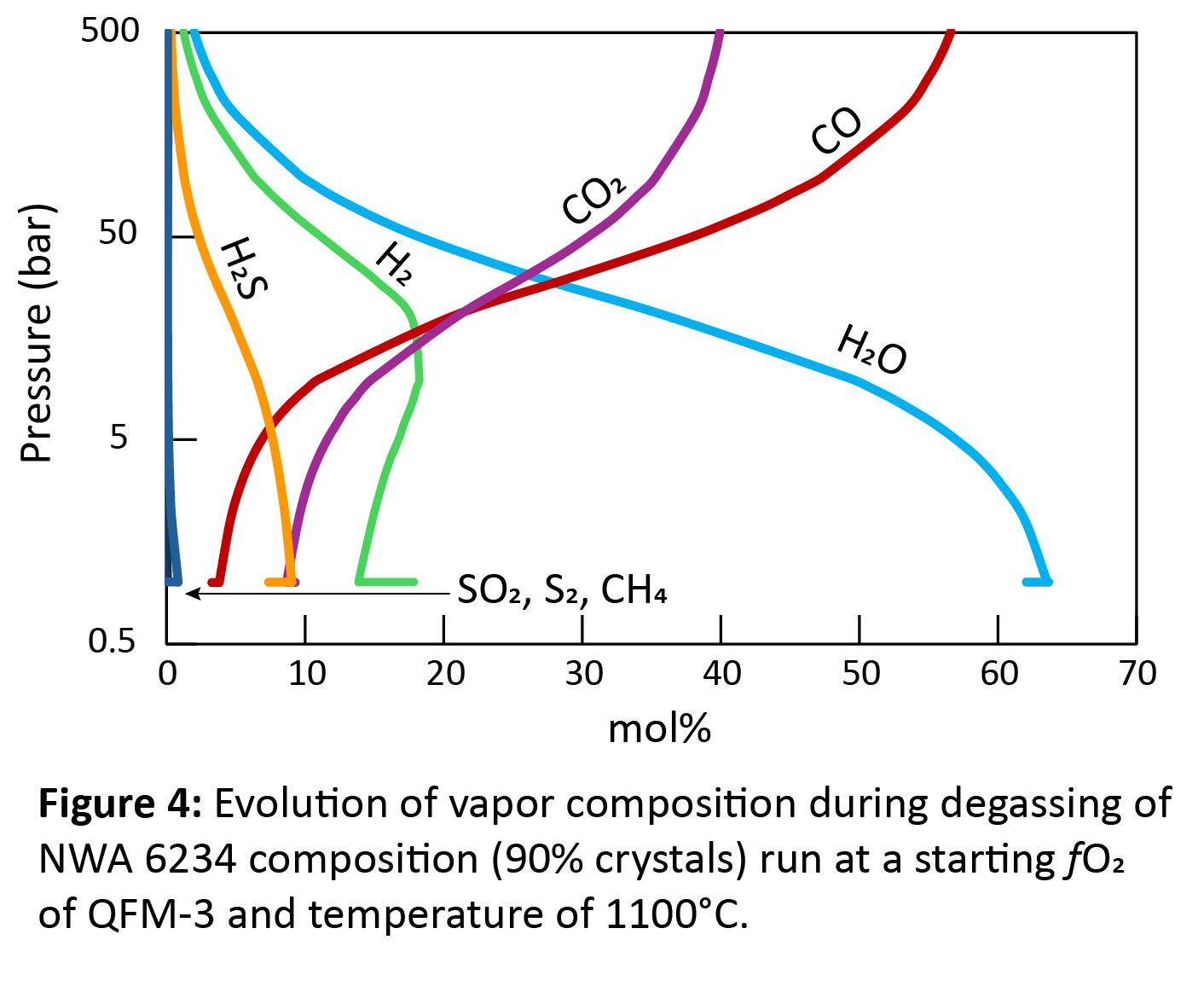

Results and Discussion: All models displayed oxidation through degassing from decompression (Figs. 2-3). However, the extent of oxidation depends on the composition of the melt and the initial fO2 of the melt before any degassing. While degassing from decompression consistently increased fO2, degassing during cooling generally decreased fO2, unless the melt was highly evolved (90-99% crystals)(Figs. 2-3). The composition of the vapor as the sample degassed during decompression was similar for all model runs. Initially, the vapor consisted of C-species (Fig. 4), which did not lead to significant changes in fO2 (Fig. 1); however, at pressures <100 bar, H-species become dominant, which is when the largest oxidative increases occur. For NWA 5789, the maximum oxidative increase (Δ+1.5) occurred when the melt had only crystallized 10-20%. Generally, however, the runs that showed the largest oxidative increases were those where the melt had crystallized 90-99% (Figs. 2-4). The largest increase in fO2 occurred in models run at QFM-4, with a Δ+1.5-2.75 log unit change seen. The smallest redox change occurred in models run at QFM-2, with a Δ+0.5-1 log unit change. This may explain why depleted and intermediate shergottites (Fig. 1) show the largest fO2 changes – they have magmatic fO2s of QFM-3 to QFM-4. The oxidative changes reported in the poikilitic shergottites studied could be replicated with the degassing models (Fig. 2). However, samples that had the greatest increase in fO2 required extensive crystallization (90-99%) to have occurred before degassing. This work suggests that the large fO2 changes seen in shergottites do not require martian magmas to be particularly hydrous to degas or require extensive auto-oxidation to occur. Additional models attempting to replicate the redox changes of other poikilitic, olivine-phyric, and basaltic/gabbroic shergottites are ongoing.

References: [1] Herd C.D.K., and Benaroya S. (submitted). [2] Castle N. and Herd C.D.K. 2017. MaPS 52, 125–146. [3] Peslier A.H. et al. 2010. GCA 74, 4543–4576. [4] Rahib R.R. et al. 2019. GCA 266, 463–496. [5] Shearer C.K. et al. 2013. GCA 120, 17–38. [6] Combs, L.M. et al 2019. GCA 266, 435–462. [7] Ardia P. et al. 2013. GCA 114, 52–71. [8] Armstrong L.S. et al. 2015. GCA 171, 283–302. [9] Ding, S. et al. 2014. GCA 131, 227–246. [10] Iacono-Marziano G. et al. 2012. GCA 97, 1–23. [11] Li Y. et al. 2017. JGR: Planets 122, 1300–1320. [12] Stanley B.D. et al. 2014. GCA 129, 54–76. [13] Sun C. and Lee C-T. 2022. GCA 338, 302–321. [14] Gross J. et al. 2011. MaPS 46, 116–133. [15] Filiberto J. et al. 2012. MaPS 47, 1256–1273. [16] Basu Sarbadhikari A. et al. 2009. GCA 73, 2190–2214. [17] O’Neal E.W. et al. 2024. GCA 373, 122–135. [18] Ghiorso M.S. and Gualda G.A.R. 2015. Cont. Min. & Petro. 169, 53. [19] Gualda, G.A.R. et al. 2012. J. of Petro. 53, 875–890. [20] Gaillard F. et al. 2013. Space Sci. Rev. 174, 251–300. [21] McCubbin F.M. et al. 2012. Geology 40, 683–686. [22] Paquet M. et al. 2021. GCA 293, 379–398. [23] Righter K. et al. 2009. EPSL 288, 235–243. [24] Stanley B.D. et al. 2011. GCA 75, 5987–6003.

How to cite: Benaroya Fucile, S. and Herd, C. D. K.: Degassing as the cause of the large redox variations seen in shergottites, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-873, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-873, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

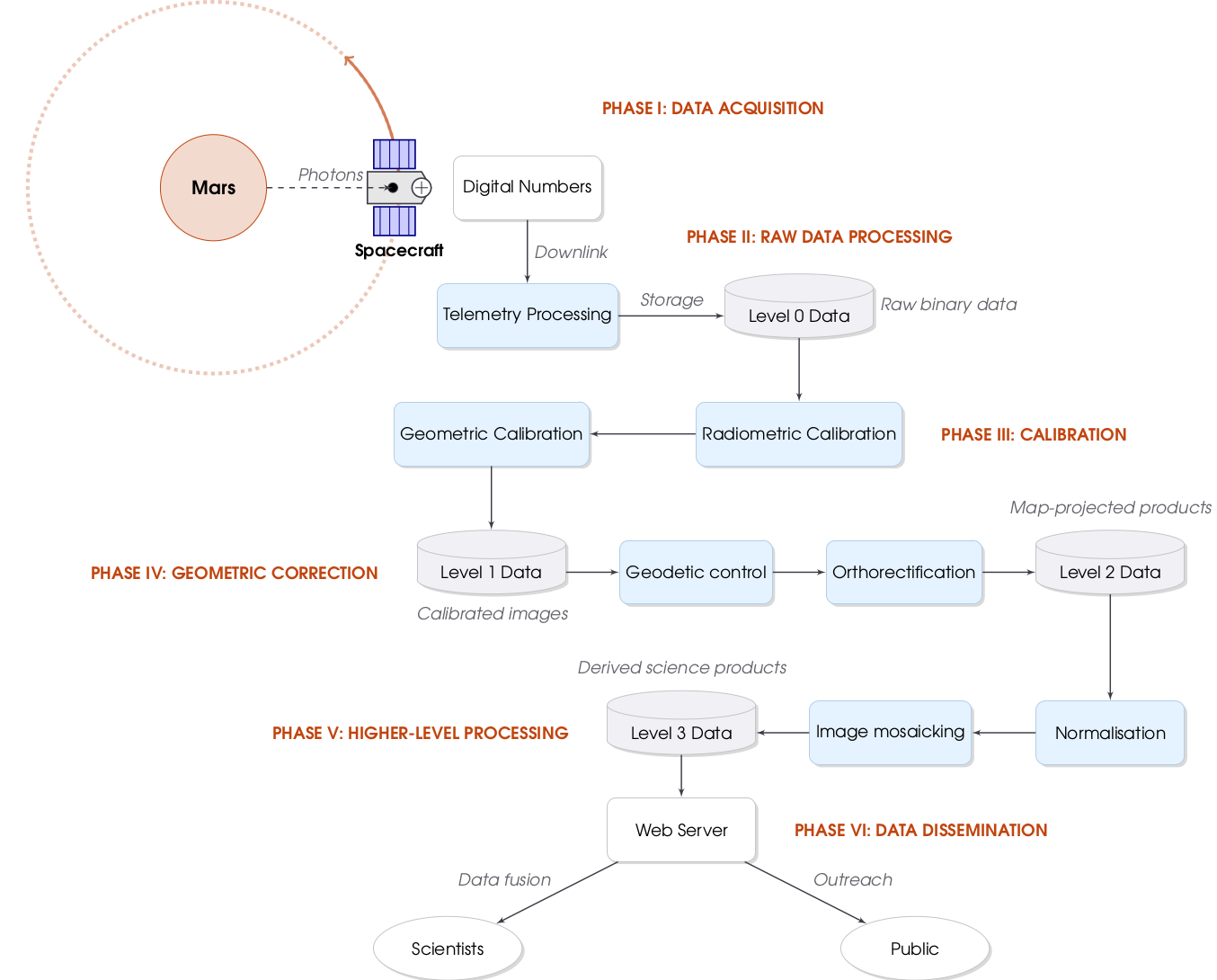

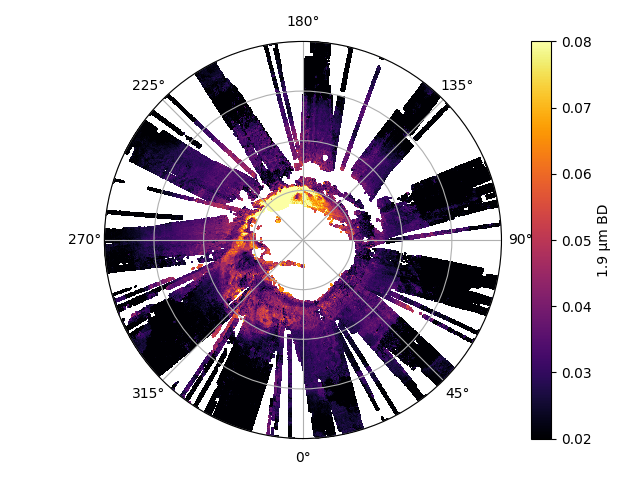

During >17 years observing Mars from orbit, the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) collected 2 main types of spectral images, targeted images at 18 or 36 m/pixel that utilized the instrument's full 544-wavelength hyperspectral capability, and mapping image strips that returned fewer channels at reduced spatial resolution. Targeted images cover ~3% of Mars at very high resolution, focusing on key exposures that reveal primary and secondary mineral assemblages and their geologic relations. Mapping image strips cover intervening areas to provide spatial continuity in mineral mapping, find new sites for targeted observations, and allow geologic relations to be extrapolated over the Martian surface [1].

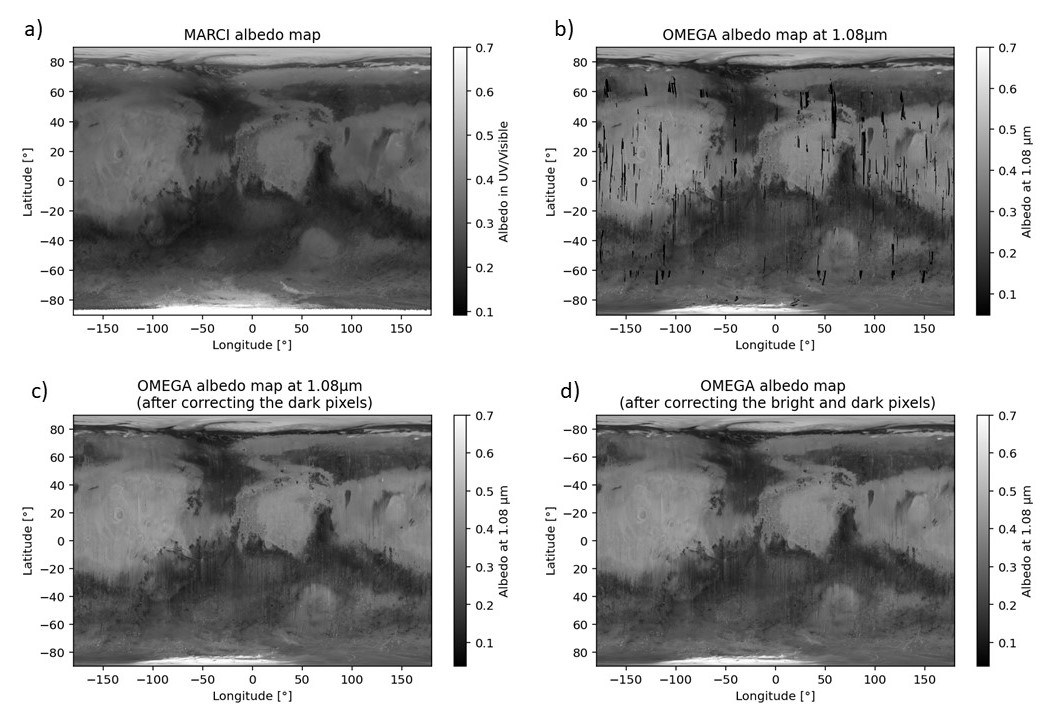

Two primary mapping modes were used. (A) VNIR+IR multispectral mapping was CRISM’s original mapping mode. CRISM spent most of its observing time in this mode or its derivatives for as long as cryocoolers for the IR detector remained functional. 73 wavelengths of returned data were selected to characterize depths of atmospheric gas and mineral absorptions known to be present from OMEGA data including olivine, pyroxene, hematite, smectite clay, and hydrated sulfate [2]. Spatial sampling at 10x pixel binning yielded a pixel scale of 180 m, covering ~86% of Mars. A subset of the data covering 39% of Mars had extended 262-channel coverage to more accurately measure subtly different absorptions due to newly discovered carbonates, hydroxysulfates, hydrated silica, and higher metamorphic grade hydrous silicates. (B) VNIR-only hyperspectral mapping was performed whenever cryocoolers were off, to map Fe-bearing silicates, oxides and sulfates. Most areas are covered by data using 5x pixel binning, yielding 90-m effective pixels including 90 VNIR channels with useful signals. Gaps are filled by VNIR mapping using 10x pixel binning, yielding 180-m effective pixels. Together, VNIR hyperspectral mapping modes cover >99% of Mars.

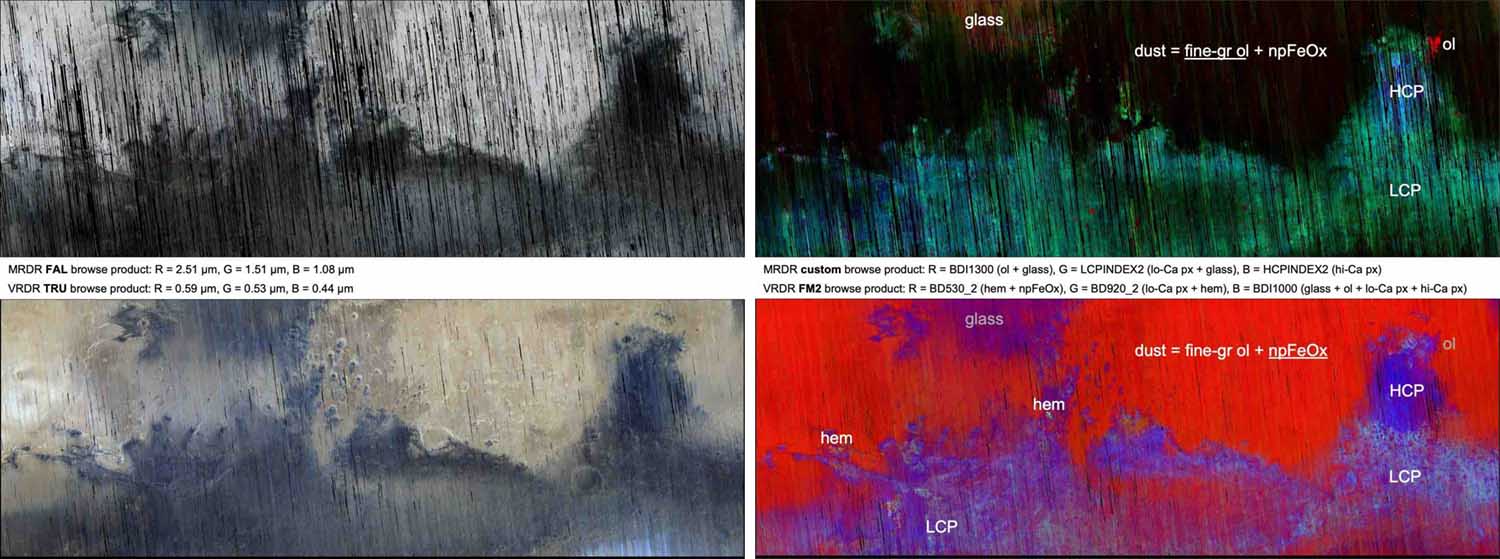

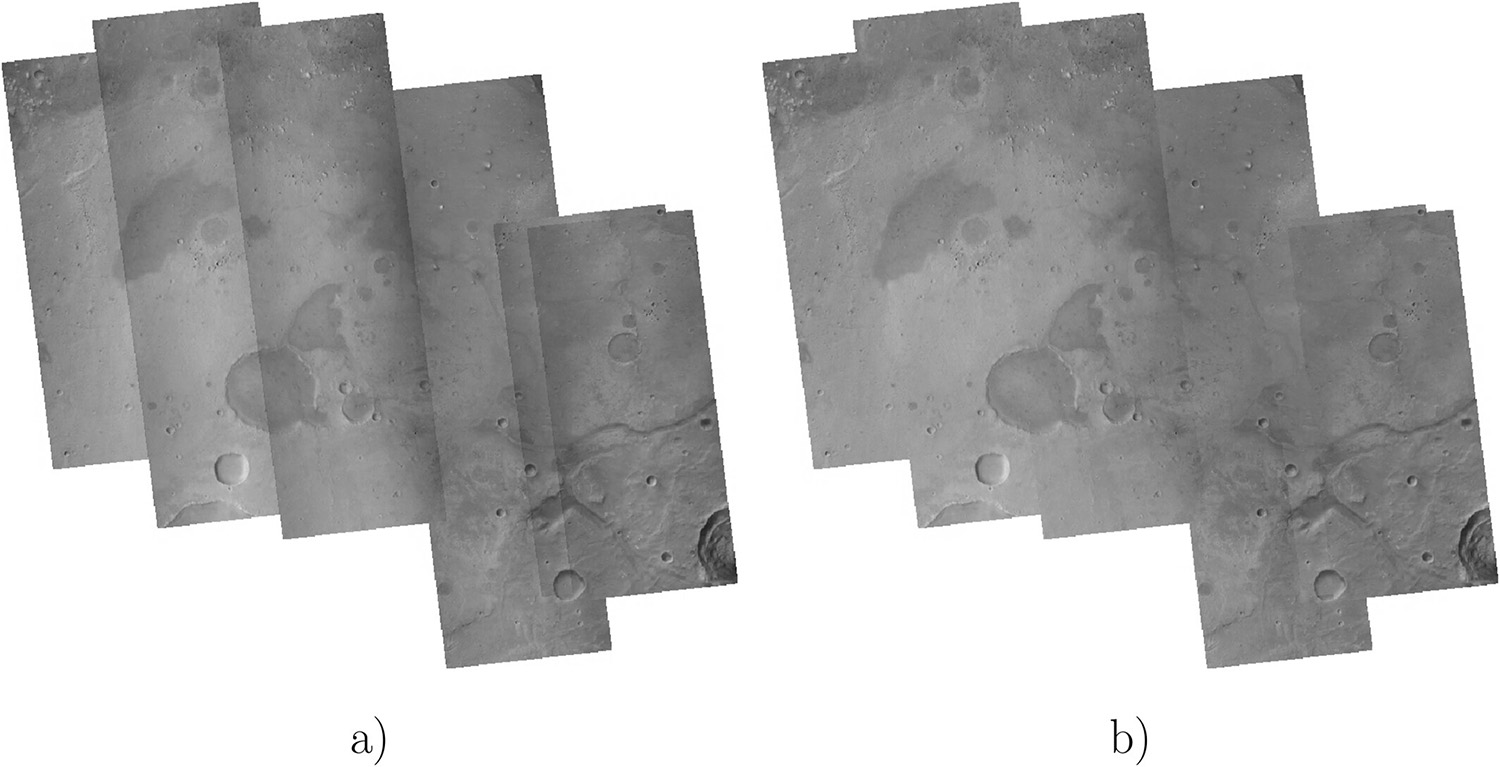

VNIR+IR multispectral data were assembled into a near-global mosaic of mapping strips divided into 1764 ~5°x5° tiles with a sampling of 327 pixels per degree (ppd), Multispectral Reduced Data Records or MRDRs; VNIR hyperspectral data were assembled into a parallel set of tiles with twice the spatial resolution (654 ppd), VNIR Hyperspectral Data Records or VRDRs. Both data sets are available in the PDS (https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/mro/crism.htm). Using procedures described in detail by Seelos et al. [3] reflectance data have been processed to remove optical and instrument artifacts, correct photometric effects of illumination to a normal solar incidence, and normalize atmospheric opacities to parts of the dataset collected under clearest atmospheric conditions. Both data sets include spectral reflectance as well as derived spectral indices that serve as mineral indicators, plus pixel-by-pixel information that relates mosaicked data back to source mapping strips.

Figure 1 compares MRDR and VRDR data sets, over the first 8 Mars charts (out of 28, excluding polar regions) of VRDR tiles released to the PDS as of 7 May 2025 (494 of 1764 tiles). The "browse products" shown are combinations of spectral reflectances and/or spectral indices as defined by Viviano et al. [4]. In MRDR IR "false color" (upper left), most areas appear in shades of gray due to the relatively "flat" spectral reflectance at IR wavelengths, with the exception of pale blue and green tones in areas of hydrated mineralogy. In contrast, VNIR enhanced "true color" (lower left) varies from dark reddish gray to bright red, due to differences in coverage of gray mafic sand and rock by dust having a red visible spectral slope due to nanophase ferric oxides (npFeOx). The VRDRs have superior spatial continuity and 2x-higher spatial resolution. MRDR coverage of IR wavelengths (upper right) measures centers and shapes of broad absorption centered near 1 and 2 µm in the spectral indices BD1300, LCPINDEX2, and HCPINDEX2. The combinations of values distinguish low- and high-Ca pyroxenes, olivine, and Fe-bearing glass (in green, blue, red, and orange tones respectively). VRDR coverage of Fe2+ and Fe3+ absorptions at 0.4-1.02 µm (lower right), measured in the spectral indices BD920_2 and BDI1000VIS, discriminates low- and high-Ca pyroxene (in cyan and blue tones respectively) but does not uniquely discriminate olivine or glass. The BD530_2 and BD860_2 or BD920_2 spectral indices in the VRDRs indicate locations rich in crystalline hematite. Additional VRDR spectral indices including RBR–in concert with IR indices – can together indicate other ferric phases such as the oxyhydroxide goethite and the ferric sulfate copiapite where they occur. More than two dozen additional spectral indices in the MRDR data discriminate the wide variety of hydrated and hydroxylated silicates, oxides, and sulfates, and hydrated silica and carbonate phases detected in CRISM data [4].

SUMMARY: Over 17 years operating in Mars orbit, CRISM collected two major global spectral maps of Mars. The image strips forming each map were corrected for artifacts and normalized to clear atmospheric conditions with atmospheric gas absorptions removed. The data are available to the community as corrected spectral reflectance as well as derived spectral indices that serve as indicators of various minerals, plus pixel-by-pixel information that relates mosaicked data back to source mapping strips.

Figure 1. IR false color (upper left) and VNIR enhanced true color (lower left) browse product maps covering the first eight Mars charts of VRDR deliveries. IR (upper right) and VNIR (lower right) browse products show spectral indicators of Fe mineralogy. Spectral absorptions at IR wavelengths distinguish primary mafic mineralogies. VNIR wavelengths distinguish low- and high-Ca pyroxene as well as a number of ferric minerals including crystalline hematite.

References: [1] Murchie, S. et al. (2009) J. Geophys. Res., 114, E00D07. [2] Bibring, J.-P. et al. (2005) Science, 307, 1576-1581. [3] Seelos, F. et al. (2024) Icarus, 419, 115612. [4] Viviano, C. et al. (2014) J. Geophys. Res., 119, 1403-1431.

How to cite: Murchie, S., Seelos, F., Hancock, K., Stephens, D., Poffenbarger, R., Romeo, G., Viviano, C., Frizzell, K., and Packer, L.: CRISM Global Visible/Infrared Spectral Maps of Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-136, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-136, 2025.

Introduction

Earth's prebiotic chemistry is based on water and thermal sources (internal or external to the Earth)1,2. In contrast, the prebiotic chemistry of extraterrestrial systems (Mars, Europa, Titan, Enceladus, etc.) is primarily driven by radiation sources3–5. Recent work leveraging Martian and ocean world natural and synthetic analog materials was used to classify biotic and abiotic organics in the context of multiple planetary missions (with Curiosity, Perseverance, Rosalind Franklin, and Dragonfly)6–9. Our experiments yielded a chemical network that abiotically produced building blocks of life (e.g., amino acids up to small-peptides and thiamine and nucleobases up to nucleotides) when synthetic analogs were hydrolyzed in contact with salts and/or exposed to X-/Ɣ-rays and proton irradiation7,10. The different irradiation simulations on natural and synthetic analog materials analyzed by spaceflight instruments and/or high-resolution mass spectrometry assessed the question: How fast may the transition from prebiotic abiotic chemistry to biotic chemistry take place? A “primitive biochemistry transition” would occur and contradicts the expectation of a clear biotic-abiotic boundary between the production of polymers abiotically and biologically in a primitive environment. Indeed, our experiments and some meteoritic data revealed the production of small biopolymers abiotically from a few hundred to tens of thousands of years10–12.

Materials and Methods

To address the influence of different radiation sources on organic matter transformation as a pure standard or in a matrix/medium analog to extraterrestrial surfaces, we got access to multiple radiation facilities (SOLEIL-France and CLS-Canada synchrotron for X-rays, GSFC-NASA-USA for Ɣ-ray and protons radiations) and analyzed with X-ray, infrared spectroscopy and GC-MS/orbitrap.

To simulate Mars near surface environment, we first studied soft/mid X-rays that could be indirectly produced by the main elements in the Martian regolith (secondary X-rays by carbon (0.28 keV), silica (1.74 keV), sulfur (2.31 keV), chlorine (2.62 keV), or iron (6.40 keV)). Those experiments focused on amino acids (L-Ala, L or D/L-Phe), peptides (Ala-Gly), carboxylic acids (trimesic, lignoceric, and benzoic acids), nucleobases (adenine and uracil), and organics detected by the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) at Gale crater (chlorobenzene and thiophene).

We then simulated the radiative conditions at higher energies for Mars and ocean worlds (using γ-rays at 1-300 krad equivalent to 6 months-1000 Titan years’ simulation, for instance, and protons at 200 MeV – e.g., a few Titan months) and chemical environment that tropospheric aerosols or surface deposits may undergo on Titan to forecast Dragonfly operations, analysis, and interpretations.

Results

Low radiation energies enhance the production of building blocks of life (e.g., nucleobases, amino acids, sugars) (Fig. 1).

Low eradiation energies induce interactions between organic matter and inorganic soluble or solid material (bond and/or form organo-mineral/salt products).

While low energy radiation enhanced the production of building blocks of life (BBLs), high energy radiation degraded faster the prebiotic precursors than produced the BBLs (Fig. 2). High radiation energies (photons and particles) benefit to the polymerization.

Conclusions

Within protected environments (e.g., Mars subsurface environments – below 10 cm – from SAM-MSL data and investigation for MOMA-ExoMars), biosignatures may be preserved for at least 100 million years thanks to salts.

A “primitive biochemistry transition” may have occurred in crater impacts few billion years ago (e.g., at Gale and Jezero craters) and contradicts the expectation of a clear biotic-abiotic boundary between the production of polymers abiotically and biologically in a primitive environment. Indeed, our experiments and some meteoritic data revealed the abiotic production of small biopolymers from a few hundred to tens of thousands of years driven by radiation and a catalytic substrate.

References

- Westall, F. et al. A Hydrothermal-Sedimentary Context for the Origin of Life. Astrobiology 18, 259–293 (2018).

- Westall, F., Brack, A., Fairén, A. G. & Schulte, M. D. Setting the geological scene for the origin of life and continuing open questions about its emergence. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 9, (2023).

- Cooper, J. F., Johnson, R. E., Mauk, B. H., Garrett, H. B. & Gehrels, N. Energetic Ion and Electron Irradiation of the Icy Galilean Satellites. Icarus 149, 133–159 (2001).

- Cockell, C. S. & Andrady, A. L. The Martian and extraterrestrial UV radiation environment--1. Biological and closed-loop ecosystem considerations. Acta Astronaut 44, 53–62 (1999).

- Dartnell, L. R., Desorgher, L., Ward, J. M. & Coates, A. J. Modelling the surface and subsurface Martian radiation environment: Implications for astrobiology. Geophysical Research Letters 34, (2007).

- Boulesteix, D. et al. Geochemical and Metabolomic study of few Yellowstone spring systems over a range of pH. in Life in the Sub Surface: Habitats, Species, Metabolism and Survival Strategies (Angra do Heroismo, Portugal, 2023).

- Buch, A. et al. Influence of the secondary X-Rays on the organic matter at Mars’ near-surface. in AGU Fall Meeting 2022 P12A-08 (Chicago, United States, 2022).

- Boulesteix, D. et al. Extremophile Metabolite Study to Detect Potential Biosignatures and Interpret Future Gas Chromatography-Mass spectrometry Ocean Worlds in situ analysis (e.g. Dragonfly mission with its DraMS instrument and EuropaLander with its EMILI instrument). in AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts vol. 2022 P55G-1650 (2022).

- Millan, M. et al. Sedimentary Organics in Glen Torridon, Gale Crater, Mars: Results From the SAM Instrument Suite and Supporting Laboratory Analyses. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 127, e2021JE007107 (2022).

- Boulesteix, D. et al. Titan Simulation for DraMS Analysis and Prebiotic Chemistry Interpretation Using Analog Materials Exposed to Gamma-rays and Protons. AGU24 (2024).

- Schmitt-Kopplin, P. et al. High molecular diversity of extraterrestrial organic matter in Murchison meteorite revealed 40 years after its fall. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, 2763–2768 (2010).

- Barks, H. L. et al. Guanine, adenine, and hypoxanthine production in UV-irradiated formamide solutions: relaxation of the requirements for prebiotic purine nucleobase formation. ChemBioChem 11, 1240–1243 (2010).

How to cite: Boulesteix, D., Buch, A., Masson, G., Szopa, C., Freissinet, C., Trainer, M., Eigenbrode, J., and Chou, L.: Radiation-driven Prebiotic Chemistry and Biosignatures Detection, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-411, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-411, 2025.

Keywords: Polygon, Qaidam Basin, Subsurface fluid, Halite crust, Gypsum raised rim, Mars

Abstract:

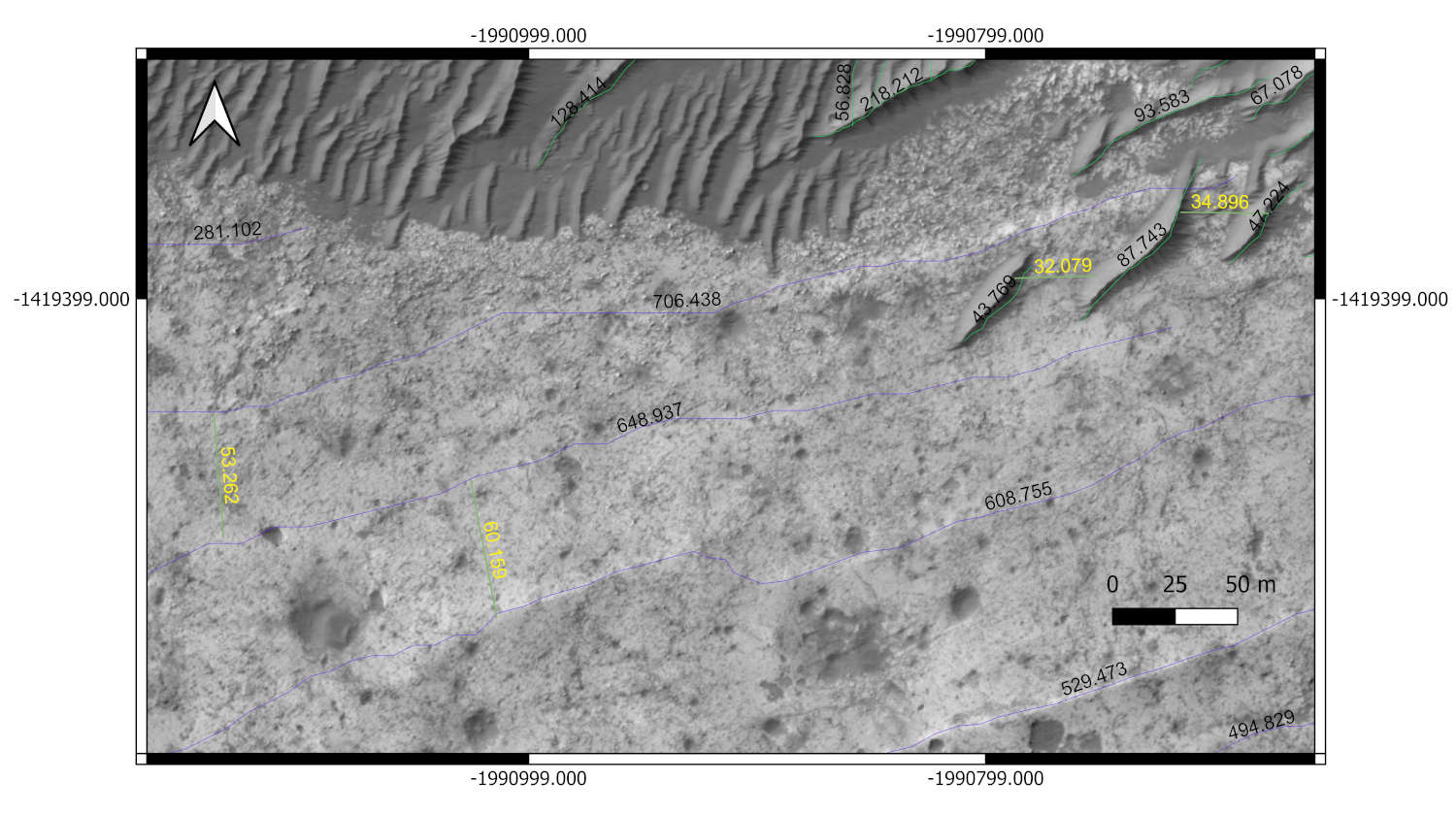

Polygonal landforms ranging in size from a few meters to several hundred meters are present in ancient salt playas on Earth and Mars (Anglés and Li, 2017). The formation of these landforms may provide information about the paleoclimate of Mars. The Qaidam Basin is one of the highest, largest, and driest deserts on Earth, located in a dry, cold, and high ultraviolet environment similar to the surface of Mars (Xiao et al., 2017). The historically hyperarid climate of the Qaidam Basin has allowed the development of extensive polygonal landforms with diverse geometric and genetic types. Here we report a terrain characterized by polygons with raised rims, ranging in size from approximately 60 to 120 meters, and exhibiting spatial variation in mineral composition and geometry from the Dalangtan area of the western Qaidam Basin on the Tibetan Plateau.

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) was used to capture high-resolution aerial imagery and generate a high-resolution digital elevation model (DEM) through photogrammetric software (Li et al., 2022). Spatially, the polygons in the northeastern part of the study area have complete rims, while the polygons in the southwest have incomplete rims (Fig .1). Surface and subsurface samples were collected at 6-meter intervals from the center to the rim of the polygons and analyzed for mineral composition and content by X-ray diffraction (chung et al., 1974). These polygons consist of a halite crust in the subsurface and raised rims formed mainly of gypsum. In some areas, the polygonal rims are broadened and form boundary belts that are up to ~30 m wide and about 1.2 m high.

Through spatial and mineral analysis, we propose a formation mechanism for polygonal landforms: the formation of the halite crust in the subsurface re-directs upward migration of evaporitic pore fluids that accumulate gypsum deposits to form the wide polygonal boundary belts (Lasser et al., 2023; Fig. 2). We suggest that the similarly sized polygons with raised rims on Mars have similar lateral and vertical structures caused successively by the strong evaporation of lacustrine brines and subsurface pore fluids (Zhu et al., 2023).

Figure 1. Digital elevation model (DEM) of the study area generated by an unmanned aerial vehicle survey.

Figure 2. Schematic representations of the formation of the raised rims/boundary belts of the pan-like polygons in the Qaidam Basin. The early stage is characterized by the drying of lacustrine (left column). Continued evaporation causes the surface to dry out and form polygonal cracks. In the middle stage, the halite crust begins to form and diverts the evaporative fluids, and gypsum begins to accumulate at the rim (middle column). In the development stage, the halite crust thickens, and more gypsum is deposited to widen the polygonal rims into wide belts (right column).

References

Anglés, A., Li, Y. (2017). The western Qaidam Basin as a potential Martian environmental analogue: An overview[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 122(5), 856-888.

Xiao, L., Wang, J., Dang, Y., Cheng, Z., Huang, T., Zhao, J., Xu, Y., Huang, J., Xiao, Z., Komatsu, G. (2017). A new terrestrial analogue site for Mars research: the Qaidam Basin, Tibetan Plateau (NW China)[J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 164, 84-101.

Dang, Y., Xiao, L., Xu, Y., Zhang, F., Huang, J., Wang, J., Zhao, J., Komatsu, G., Yue, Z. (2018). The polygonal surface structures in the Dalangtan Playa, Qaidam Basin, NW China: controlling factors for their formation and implications for analogous Martian landforms[J]. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 123(7), 1910-1933.

Li, Z., Wu, B., Liu, W. C., Chen, Z. (2022). Integrated photogrammetric and photoclinometric processing of multiple HRSC images for pixelwise 3-D mapping on Mars[J]. In IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 60, 1-13.

Chung, F. H. (1974). Quantitative interpretation of X-ray diffraction patterns of mixtures. II. Adiabatic principle of X-ray diffraction analysis of mixtures[J]. Journal of Applied Crystallography, 7(6), 526-531.

Lasser, J., Nield, J. M., Ernst, M., Karius, V., Wiggs, G. F., Threadgold, M. R., Beaume, C., Goehring, L. (2023). Salt polygons and porous media convection. Physical Review X, 13(1), 011025.Salt polygons and porous media convection[J]. Physical Review X, 13(1), 011025.

Zhu, J., Wu, B., Zhao, T., Li, Y. (2023). Polygons with halite-crusted floors and gypsum-raised rims in western Qaidam Basin and implications for polygonal landforms on Mars. Geomorphology, 443, 108934.

How to cite: Zhu, J., Wu, B., and Li, Y.: A study of polygonal landforms in the western Qaidam Basin and implications for polygonal landforms on Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-244, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-244, 2025.

Introduction:

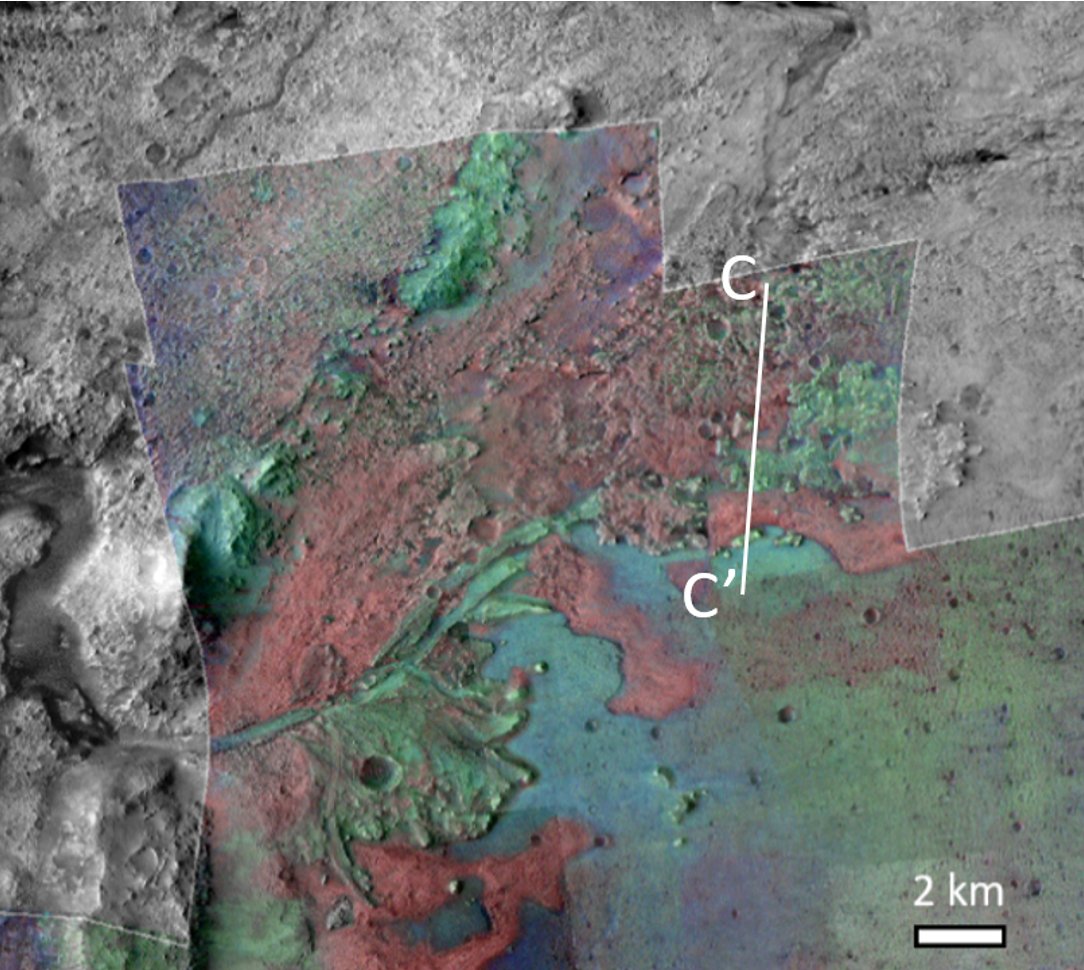

Understanding the relationship between the western and northern deltas in the Jezero crater on Mars is crucial for the reconstruction of the water history in this region. The northern delta appears to be more eroded and older than the western delta; however, contemporaneous northern and western fan building was also recently proposed ([1], [2]). In our study, we explore the origin of the LCP (low-calcium pyroxene)/smectite and olivine/carbonate spectral units, which were found in both deltas and which may record the interaction between them in the past [2] (Fig. 1). We use topographic and compositional data to model potential deposition of the sediments from the western inlet on the northern delta. Our results shed light on the interconnection between the western and northern deltas, establish their relative age and suggest that Neretva Vallis (western inlet) could be the source of the LCP/smectite unit on both deltas in Jezero.

Fig. 1. CRISM Mafic map, adapted from [1]; Green – LCP/smectite; red – olivine/carbonate; blue – High-calcium pyroxene. CC’ profile is shown in Fig.2.

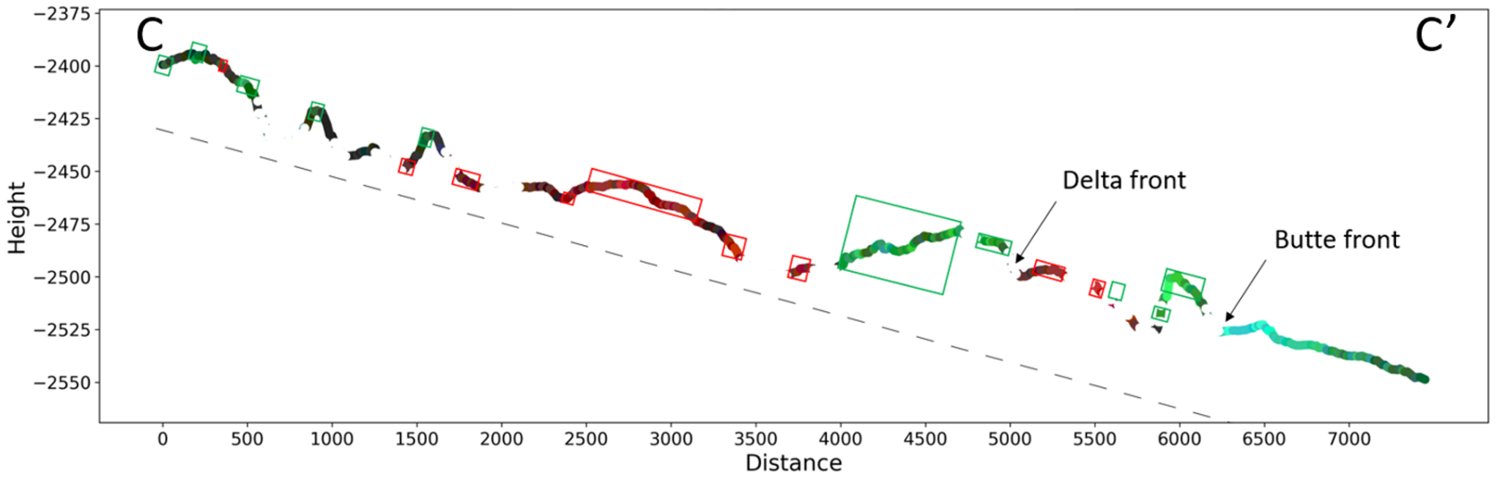

Fig. 2. Example of the topographic-compositional profile (profile line is on Fig. 1).

Data:

CRISM spectral data [2] and the Mars 2020 Science Investigation CTX DEM Mosaic (20 m/pixel) and its corresponding ortho-mosaic (5 m/pixel, [3], [4]) were used.

Methodology:

Based on topographic and compositional data we plotted topographic-compositional profiles that show changes in topography and composition simultaneously (Fig. 2).

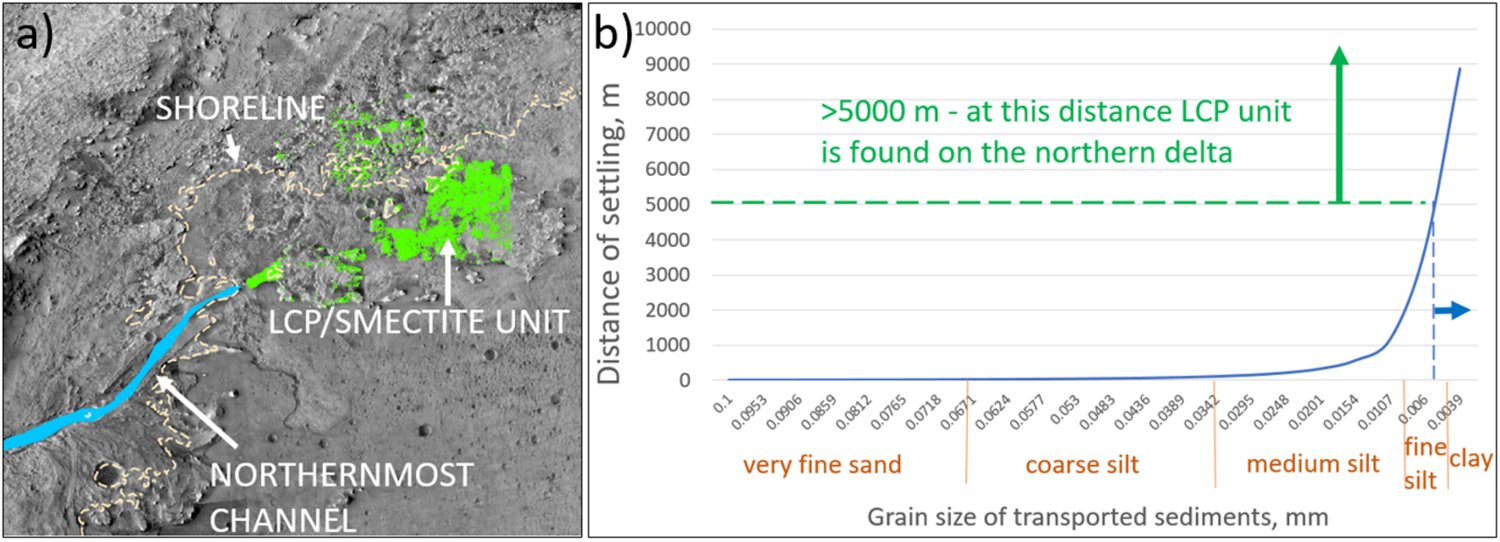

To model the hypothesized deposition of the sediments coming from the western inlet through the northernmost channel located within the western delta (Fig.3a), we combined two equations: 1) sediment settling velocity [5] – for the vertical movement of sediment particles and 2) conservation of volumetric flow rate before and after the river enters the lake – for the horizontal movement of the sediment particles. Using the sediment transport equations of [6], we determined that particles up to 5 mm in size are transported in suspension through the above-mentioned channel. Therefore, we used a grain size range from 5 mm (small pebble) to 0.0039 mm (clay) for our model calculating the distance at which sediments transported by the northernmost channel of the western delta can be deposited on the northern delta.

Results:

Topographic-compositional profiles show that the LCP/smectite unit is stratigraphically higher than the olivine/carbonate unit, but does not reveal prominent correlations between separate delta outcrops that would represent the parallel layering typical of Gilbert-type deltas. Therefore, the LCP/smectite unit had to overlie the olivine/carbonate unit when the northern delta was already eroded to its present topography. According to the CRISM data, the closest possible source of the LCP/smectite unit is the western delta and the watershed of the western inlet. At the same time, the CTX DTM shows that a scenario where the northernmost channel of the western delta is subaerial (above the shoreline), while the northern delta is subaqueous could be possible (Fig.3a). Therefore, we hypothesize that the LCP/smectite unit consists of material transported by the northernmost channel of the western delta which is connected to the western inlet. Our model shows that fine silt can be deposited at a distance of 5,000 – 10,000 m from the end of the channel – at this distance the LCP/smectite unit is indeed found on the northern delta (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. a) Overview map with studied features; b) Results of modeling, showing that fine silt will be deposited on the southern part of the northern delta, which coincides with the appearance of the LCP/Smectite units.

Discussion:

We validated the model using information about the minimum grain size of the western delta provided by the Perseverance rover results (in bottomsets – “<0.02 mm” for M2020-575-16 Shuyak sample [7]) and RIMFAX data, which show that the length (projected to the crater floor) of the one “topset-foreset-bottomset” sequence is approximately 135-200 m [8]. We modeled the case of deposition of western delta material only and found that sediments with the grain size “0.02 mm” form bottomsets at a distance of 192 m, agreeing with the RIMFAX data. In addition, THEMIS data [9] show low thermal inertia in the southern part of the northern delta (where LCP/smectite is located) consistent with loose fine-grained material (such as silt).

Conclusion:

We interpret the uppermost LCP/smectite unit within the northern delta as material from the western inlet deposited over already existing topography of the northern delta. This implies that there was a period when the active western inlet provided sediment to cover the already eroded northern delta. We therefore conclude that the main body of Jezero Crater's northern delta is older than the western delta but covered with the relatively thin and younger layer of silt deposits from the western inlet.

References:

[1] M. J. Jodhpurkar, et al., J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 129 (2024)

[2] B. H. N. Horgan, R. B. Anderson, G. Dromart, E. S. Amador, and M. S. Rice, Icarus, 339 (2020)

[3] F. Calef, Planetary Data System, USGS Astrogeology Science Center (2021) https://astrogeology.usgs.gov/search/map/mars_2020_science_investigation_ctx_dem_mosaic

[4] M. C. Malin, et al., J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 112(5) (2007)

[5] R. I. Ferguson, and M. Church, Journal of Sedimentary Research, 74(6), 933–937 (2004)

[6] M. G. Kleinhans, J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 110(12), 1–23 (2005)

[7] K. Farley, and K. Stack, Mars 2020 reports, Volume 2, Delta Front Campaign (2023) https://mars.nasa.gov/internal_resources/1656/

[8] S.-E. Hamran, D. Paige, F. Andersson, T. Berger, E. Cardarelli, L. Carter, H. Dypvik, P. Russell, M. Mellon, D. Nunes, and D. Plettemeier, Europlanet Science Congress 2024, EPSC2024-403 (2024). https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-403

[9] C. S. Edwards, K. J. Nowicki, P. R. Christensen, J. Hill, N. Gorelick, and K. Murray, J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 116(10) (2011). https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JE003755

How to cite: Ovchinnikova, A., Jaumann, R., Walter, S. H. G., Gross, C., Zuschneid, W., and Postberg, F.: Exploring the connection of the Northern and the Western Deltas in Jezero Crater on Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-795, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-795, 2025.

Introduction

Floor-Fractured Craters (FFCs) are a class of impact craters characterized by fractured and hummocky crater floors, often displaying features such as concentric or radial fractures, mesas, tilted blocks, and irregular topographies. These morphologies suggest post-impact modification processes that have been extensively studied across the Solar System. On Mars, the origin of FFCs is still debated, with several hypotheses proposed, including intrusive magmatism and associated doming, tectonic deformation, glacial or periglacial activity, and the migration or discharge of pressurized groundwater [1–4]. This study presents preliminary results from a detailed geological and geomorphological analysis of a small (~18 km diameter) floor-fractured crater located in the Noachian-aged terrain of Terra Sirenum (37°S, 190°E), within the broader Gorgonium Chaos basin (~240 km wide [5]). The study aims to investigate the origin of the fractures and the geological evolution of the crater, and to assess the potential roles of tectonic, magmatic, and periglacial processes [6] in shaping its morphology.

Methodology

A detailed geomorphological and stratigraphic analysis was performed by integrating high-resolution datasets, including HiRISE (25 cm/px) [7], CaSSIS (4.5 m/px) [8], CTX (6 m/px), and topographic data from MOLA [9]. Crater counting was performed on the continuous ejecta blanket using CraterTools [10] and Craterstats2 [11], applying the Hartmann and Neukum chronology system [12] and Ivanov's production function [13] to constrain the formation age of the impact. A preliminary evalution of the mineralogical composition of the crater was performed using spectral data from CRISM [14]. As a first step, we used the RGB color composites (browse products) of CRISM [15], which enable a rapid, visual and qualitative multiparametric evaluation of the spectral characteristics of the surface.

Preliminary Results and Interpretation

The interior displays typical FFC features, including a polygonal fracture network, tilted blocks, and mesas of varying elevation and morphology. These morphologies are particularly developed in the southern and central portions of the floor, which appear topographically elevated compared to the northern and eastern parts. This doming-like structure, may indicate the emplacement of a shallow magmatic intrusion beneath the crater floor, causing uplift and fracturing [3]. At the same time, several indicators point toward the involvement of cryospheric processes. The crater ejecta blanket shows a double-layered morphology, a characteristic feature of many Martian craters formed in ice-rich or volatile-rich targets [16-17]. The inner ejecta lobe is more continuous and lobate, while the outer lobe is discontinuous and thinner, consistent with ballistic deposition over an icy or volatile-rich regolith. Within the crater, some mesas appear mantled or smoothed, possibly due to deposition of later ice-related material or sublimation lag deposits. The crater size-frequency distribution (SFD) suggests an early Hesperian to late Noachian formation age (3.4 ± 0.09 Ga, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 –On the left the image shows the extent of the ejecta in red and the counting crater in yellow. The white arrows highlight the interaction of the Sirenum Fossae fractures with the crater ejecta. On the right, the plot shows the calculated age for the ejecta.

The fracture geometry and spatial distribution within the crater floor suggest at least two deformational phases: an (i) early tectonic control linked to the broader Sirenum Fossae system, and (ii) a later local doming and fracturing episode possibly due to magmatic intrusion. The CRISM-FAL (false color), MAF (mafic mineralogy), PHY (phyllosilicates), PFM (Fe/Mg-phyllo-silicates), PAL (Al-phyllosilicates) and ICE (carbon dioxide frost or ice) browse products were used to investigate the mineralogical composition of the crater and its infilling. These mineralogical maps indicate that the central/southern mesas are characterized by the presence of pyroxene, while the rim and the inner wall of the crater show signs of Fe/Mg Phyllosilicates.

Future Work

The integration of geomorphology, stratigraphy, and composition seems to support a complex interplay of tectonic, magmatic, and later cryospheric processes in the evolution of the crater. Further analysis will include (i) quantitative analysis of spectra derived from CRISM, to constrain the composition of floor and ejecta materials, and to test the possible emplacement of magmatic material and ii) the radar data from SHARAD and MARSIS, in order to assess the presence of present subsurface ice.

Acknowledgement: This work has been developed under the ASI-INAF agreement n. 2024-40-HH.0

References

[1] Schumacher S. and Zegers T. E. (2011) Icarus, V. 211, pp 305-315. [2] Sato H. et al. (2010), Icarus 207 pp. 248-264. [3] Bamberg M. et al. (2014) PSS, V. 98, pp.146-162. [4] Hanna J. C. and Phillips R. J. (2006) JGR, V. 111. [5] Wendt L. et al. (2013) Icarus 225, pp 200-215. [6] Bertoli et al. (2025), submitted to GFT&M [7]. McEwen et al. A. S (2007), JGR:Planets, V. 112. [8] Thomas et al. (2017) Space Sci. Rev. 212 (3–4), 1897–1944. [9] Smith D. E. et al. (2001), JGR:Planets, V. 106, pp. 23689 – 23722. [10] Kneissl T. et al. (2011) PSS, V. 59, pp. 1243–1254. [11] Michael G. G., and Neukum G. (2010) -EPSL, V. 294, pp. 223–229. [12] Hartmann W. K. and Neukum G. (2001) Space Science Reviews, V. 96, pp. 165 – 194. [13] Ivanov B. A. (2001), Space Science Reviews, V. 96, pp. 87–104. [14] Murchie S. et al. (2007), JGR:Planets, V. 112. [15] Viviano-Beck et al. (2014) J. Geophys. Res., V. 119, pp. 1403-143. [16] Barlow et al. (2000), JGR:Planets, V. 105, pp. 26733 – 26738. [17] Weiss D. K. and Head J. W. (2013), Geophys. Res. Lett., V. 40, pp. 3819 – 3824.

How to cite: Bertoli, S., Massironi, M., Salvatore, M. C., Baroni, C., Baschetti, B., Tullo, A., Munaretto, G., Martellato, E., Cremonese, G., Pajola, M., Hauber, E., and Faletti, M.: Geological history of a Floor-Fractured Crater in Gorgonum Chaos, Terra Sirenum, Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1494, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1494, 2025.

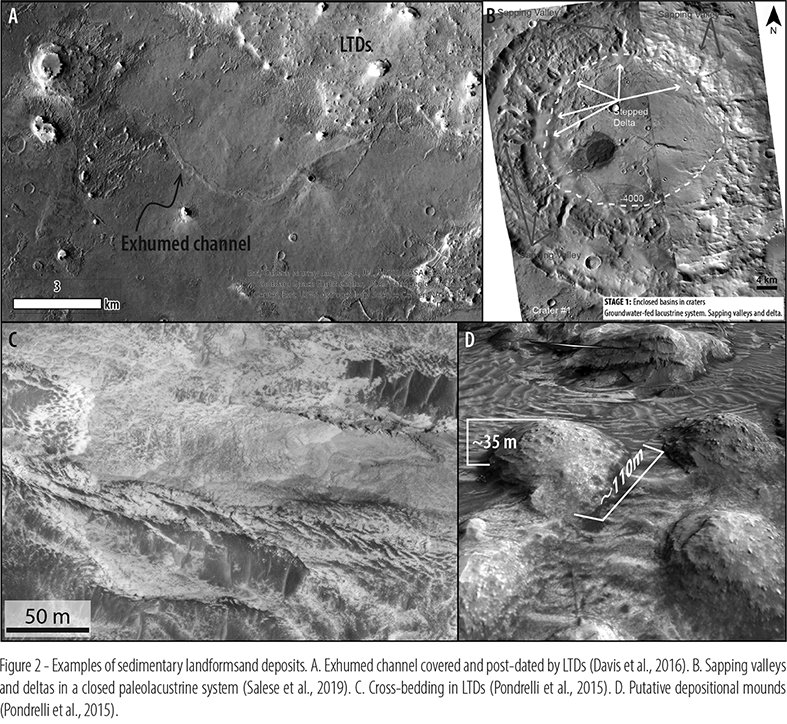

Introduction

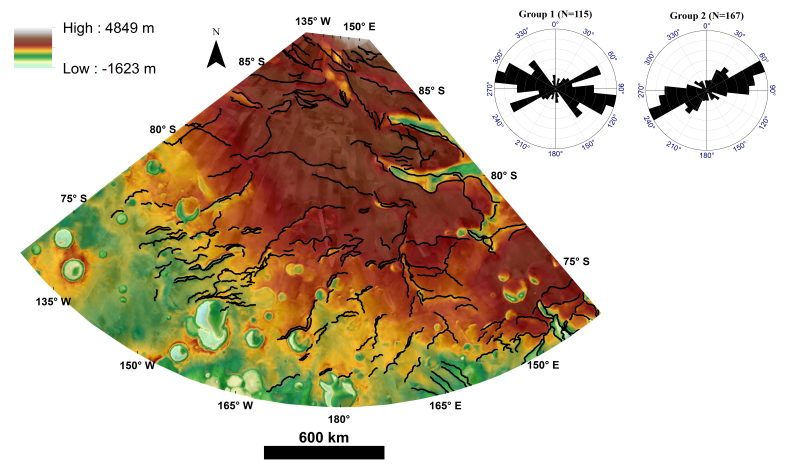

Noachis Terra, in Mars’ southern highlands, is a region which is poorly dissected by erosional fluvial landforms[1,2] but which warm/wet climate models of the early Martian climate predict should have experienced high rates of precipitation[3]. A recent study in Arabia Terra[4], another poorly dissected region of the highlands, found a network of distributed sinuous ridges. These were interpreted as fluvial sinuous ridges (FSRs), topographically inverted fluvial channel belts that are at least as old as the Noachian-Hesperian transition and interpreted to be evidence for ancient river systems with high depositional rates. Noachis is similarly aged, but has a distinctly different geological history[5], so finding FSRs here would provide evidence both for widespread ancient rivers in another part of Mars, and also suggest this style of fluvial activity was common across Mars’ highlands at this time.

Methods

We used ArcGIS Pro software to conduct a survey of a > ten million km2 study area (-35°E, -12°N; 45°E, -55°N). We used the Context Camera (CTX[6]) online global mosaic (5-6 m/pixel[7]), supplementing this with High Resolution Science Experiment (HiRISE; 25-50 cm/pixel[8]) data. We digitized FSRs at a scale of 1:50,000 and measured, calculated, and classified key features relating to each ridge segment, assigning each ridge to one of four morphotypes. We categorised ridges as either ‘certain’ or ‘confident’ based on exposure and image quality; if ridges did not meet these criteria, they were excluded.

Results/Discussion

Morphology:

‘Certain’ ridges have a combined length of more than 8,000 km. This increases to 15,000 km if including the ‘confident’ class. Here we discuss only the ridges classified as certain.

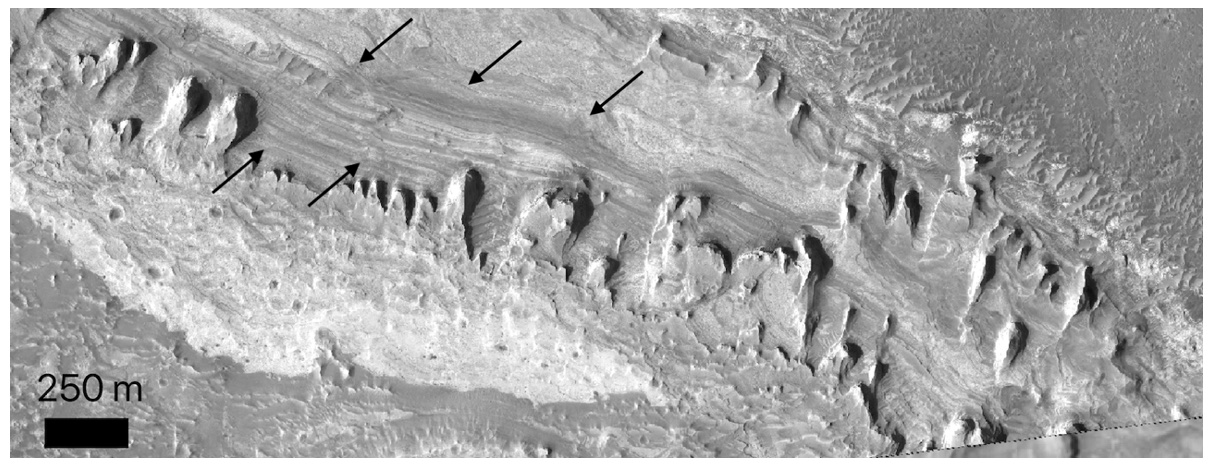

Figure 1: FSR types. Black arrows denote FSRs, white arrows denote downslope topographic trends. A) Type A: rare. B) Type B: most common, 84% of the total length for ‘Certain’ FSRs. C) Type C: narrow, pointed. D) Type D: heavily degraded chains of mounds.

Individual FSR segments are a few kilometres to tens of kilometres long. All four types are sinuous to sub-sinuous: the 30 longest segments (>20 km each) have an average sinuosity of 1.2. The ridges all appear to conform to local topographic trends, exhibit various degrees of preservation, range in width from <100 m to >3 km and exhibit 2-21 m of vertical relief. The shortest segment digitised is 200 m long and the longest is more than 78 km. Visible internal layering or structure is rare and offers little additional information. FSRs commonly record curving plan-view shapes that we interpret as meanders, branching, anastomosing, and smaller ridges connecting at oblique angles to a central wider ridge, which we interpret as tributaries joining a main channel. Ridges with branches may record avulsions or anabranching, or might represent different generations of fluvial activity stacked vertically[9].

Distribution:

The FSRs are widely distributed across Noachis Terra. They are predominantly found in local depressions, and more than 91% (in length) occur in the intercrater plains. Many distinct FSR segments can reasonably be linked to one another, suggesting that river systems many tens or even hundreds of kilometres long were present. However, there are other examples of isolated FSRs or multiple FSRs that do not align with one another, demonstrating that either shorter systems were common or that erosion has removed the evidence for longer rivers. There is little variation in distribution for type B, C, and D, though there is a significant concentration of all FSRs in and west of Greeley Crater (4°E, -37°N); this is also where most type A FSRs occur. We find few FSRs at latitudes higher than 47°S. This indicates a true absence of ridges here, but also shows that we were more conservative in identification due to icy mantling and poorer data quality this far south. The broad distribution of FSRs suggests that the water source must also have been widely distributed (e.g. precipitation). The most likely explanation for the distribution of FSRs is a protracted period (or periods) during which the regional climate was able to sustain precipitation and allow stable surface water long enough to form river systems.

Almost a quarter of FSRs can be found within, or connected to, valleys. Many of these FSRs are in the lower reaches of individual fluvial systems but in other cases FSRs transition to and from valleys. The FSRs occur as narrow, sometimes isolated sections, and are not amenable to accurate age determination using crater counting. Nevertheless, the FSRs are all on Noachian Basement units[10]. The oldest crater they are present in is Dollfus (-4.2°E, -21.4°N; ~4.08-4.013 Ga[11]), and the youngest is Bakhuysen (15.7°E, -22.7°N; ~ 3.49-3.73 Ga[11]). The maximum age of the FSRs is likely to be Noachian or Early Hesperian.

Conclusion

More than 15,000 km of FSRs occur across Noachis Terra, a region of Mars’ southern highlands that is poorly dissected by valleys. These record evidence of sustained fluvial processes, and deposition of fluvial sediment, in a region that was previously thought to lack them. They are likely to have formed during the late Noachian or Early Hesperian, suggesting an at least transiently warm and wet early Mars. These observations provide an important input into future climate models for this period, especially into those that use a lack of valleys in this region to argue against a warm, wet climate[3]. We suggest that having found FSRs in two geologically and geographically diverse, but similarly-aged highland regions on Mars[4], FSRs are likely to be present throughout many Noachian/Hesperian highland regions. Similar survey projects examining CTX data in other regions will test this hypothesis.

References

1 Alemanno et al., Earth and Space Science (2018)

2 Hynek et al., JGR: Planets (2010)

3 Wordsworth et al., JGR: Planets (2015)

4 Davis et al., Geology (2016)

5 Fassett and Head, JGR: Planets (2007)

6 Malin et al., JGR: Planets (2007)

7 Dickson et al., Earth and Space Science (2024)

8 McEwen et al., JGR: Planets (2007)

9 Hayden et al., Icarus (2019)

10 Tanaka et al., USGS (2014)

11 Robbins et al., Icarus (2013)

How to cite: Losekoot, A., Balme, M. R., Coe, A. L., and Fawdon, P.: The Fluvial History of Noachis Terra, Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1751, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1751, 2025.

Introduction

The ESA ExoMars Rosalind Franklin (EMRF) rover will launch in 2028, and land in the Oxia Planum region of Mars. The main target is Noachian phyllosilicate-rich deposits [1,2]. This region probably represents the oldest aqueous environments to be explored in situ on Mars. In this study we have investigated extensive secondary craters within the EMRF landing ellipse, to place absolute age markers in the stratigraphic framework of Oxia Planum, and identify the likely primary source crater(s). We pay particular attention to possible secondary craters from Mojave crater, due to its likely recent formation age [3] and importance as a potential source crater for martian meteorites [4].

Method

We first used the recent Mars catalogue of small impact craters [5, 6] in a small (1 x 105 km2) ‘Oxia Planum study region’. We refined the crater identification through manual crater addition, deletion, movement, and scaling. We produced a final catalogue with an extra 22,209 craters, totalling 381,584 impact craters. We applied the ‘Algorithm for the Secondary Crater Identification’(ASCI) [3] to identify possible primary and secondary impact craters. We then produced a crater size density map of possible secondary craters for the Oxia Planum study region, from which we identified acute triangle-shaped clusters (or ‘cones’) of craters. We carried out crater size-frequency distribution (CSFD) studies of previously-identified units in Oxia Planum [1] to determine model surface ages, both with and without secondary craters removed. We then merged the original catalogue of small impact craters [5, 6], with craters with diameters >1 km [7] in a larger (1.2 x106 km2) ‘context study region’. We used the same methods to identify possible primary and secondary craters, and produced a crater size density map of possible secondary craters.

Results

We separate our results into (1) the identification and analysis of secondary craters, and (2) the implications for model ages in Oxia Planum.

Secondary Craters. Of the impact craters in the smaller Oxia Planum study region, we classified 176,927 (46.4%) as primary craters, with 204,657 (53.6%) classified as secondary craters. The number of possible secondary craters has been revised down from our previous results [8]. We identified at least 13 separate clusters of craters that occur in cone shapes, with each cluster typically up to 40 km long and 20 km wide at the distal ends. These cones are oriented radially away from Mojave crater, with the median direction being 225°, similar to the median direction (222°) to Mojave crater. The cones show a distinctive size distribution of craters, with larger craters limited to the proximal (apex) region, with a gradual transition to smaller craters in the distal zone. The cones in our Oxia Planum study region are located at distances of ~700 to 930 km from Mojave. The larger, context study region contains 2,877,811 impact craters, ranging in size from 29 m to 54.4 km [5-7]. We classified 1,356,995 (47.2%) as primary craters, with 1,520,816 (52.8%) classified as secondary craters. We identify a further 13 cone-shaped clusters of secondary craters in the context study region, with ranges ~275 – 500 km from Mojave.

Figure 1. (A) Possible primary (red) and secondary (green) impact craters in our Oxia Planum study region. (B) Secondary crater size density map of same region. EMRF 1s (grey) and 3s (black) ellipse ranges are shown.

Model Surface Ages. The removal of secondary craters from CSFD studies does not affect the model surface age of the phyllosilicate units in Oxia Planum. We derive a model surface age of 3.9 Ga for the Noachian layered clay-bearing unit (lNc) of [1] using all our craters, and an identical age when using just our primary craters. This similarity is due to the lack of secondary craters at larger diameters.

Implications

Our results suggest that there are extensive secondary impact craters in Oxia Planum, with ~4000 secondaries within the EMRF 3s ellipse pattern. It is therefore likely that EMRF will encounter secondary craters during surface operations. The orientation of cone-shaped clusters of small craters indicates that the majority of secondaries are sourced from the Mojave impact crater, although larger, older secondary craters from other sources are also present. Given that the Mojave impact is estimated to have occurred 10.1 Ma [3], these secondaries can be used as absolute stratigraphic markers throughout Oxia Planum, particularly in quantifying the rate of recent and active surface processes. These secondary craters will also be important for target prioritization during in situ studies.

References: [1] Quantin-Nataf C. et al. (2021) Astrobiol. 21, 345-366. [2] Mandon L. et al. (2021) Astrobiol. 21, 464-480. [3] Lagain A. et al. (2021) Earth Space Sci. 8, e2020EA001598. [4] Werner S.C. (2014) Science, 343, 1343-1346. [5] Lagain A. et al. (2021) in GSA Spec. Paper 550, 629-644. [6] Lagain A. et al. (2021) Nature Comms. 12, 6352. [7] Robbins S.J. & B.M. Hynek (2012) JGR 117, E05004. [8] Grindrod, P.M. et al. (2023) LPSC 54, #1113.

How to cite: Grindrod, P., Collins, G., Magnarini, G., Davis, J., Fawdon, P., Favaro, E. A., Tornabene, L., Sokołowska, A., Martin-Wells, K., and Balme, M.: Extensive Secondary Impact Cratering in the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Landing Site at Oxia Planum, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-157, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-157, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

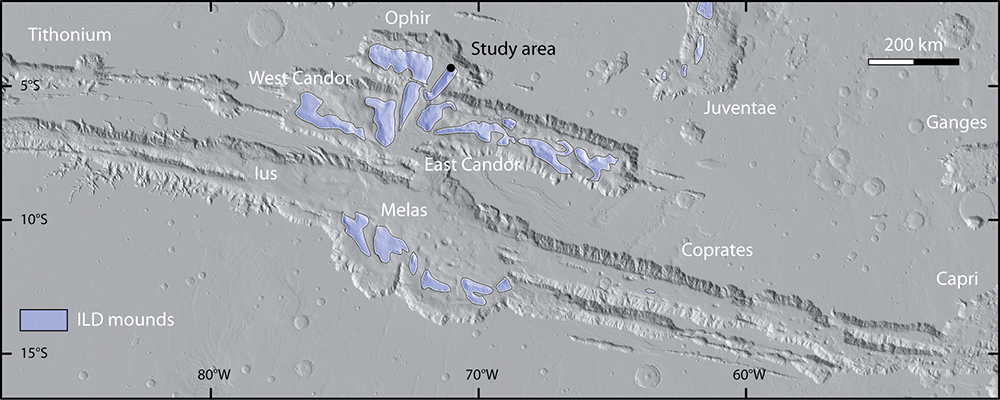

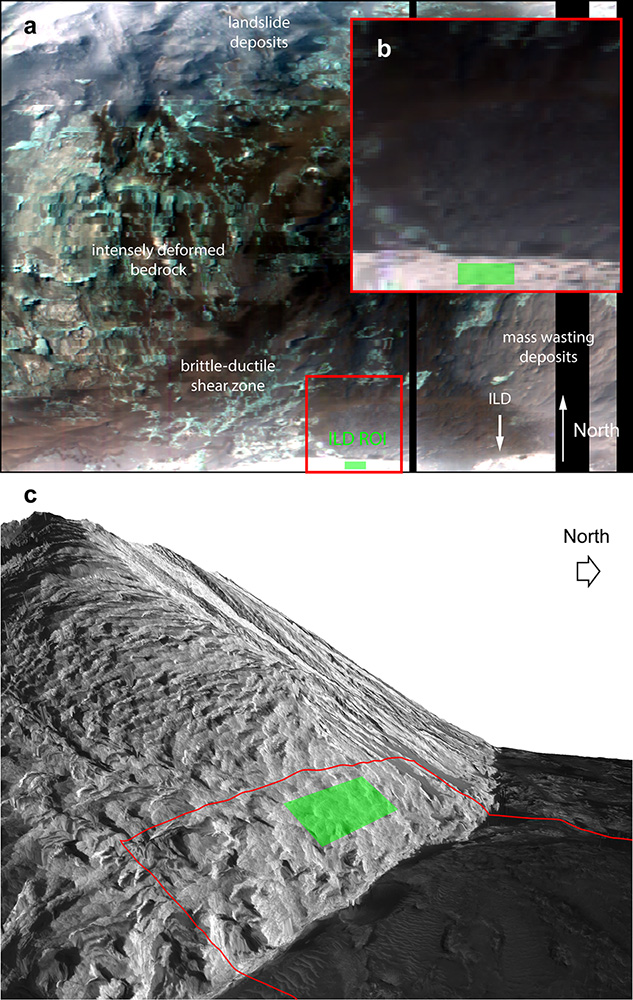

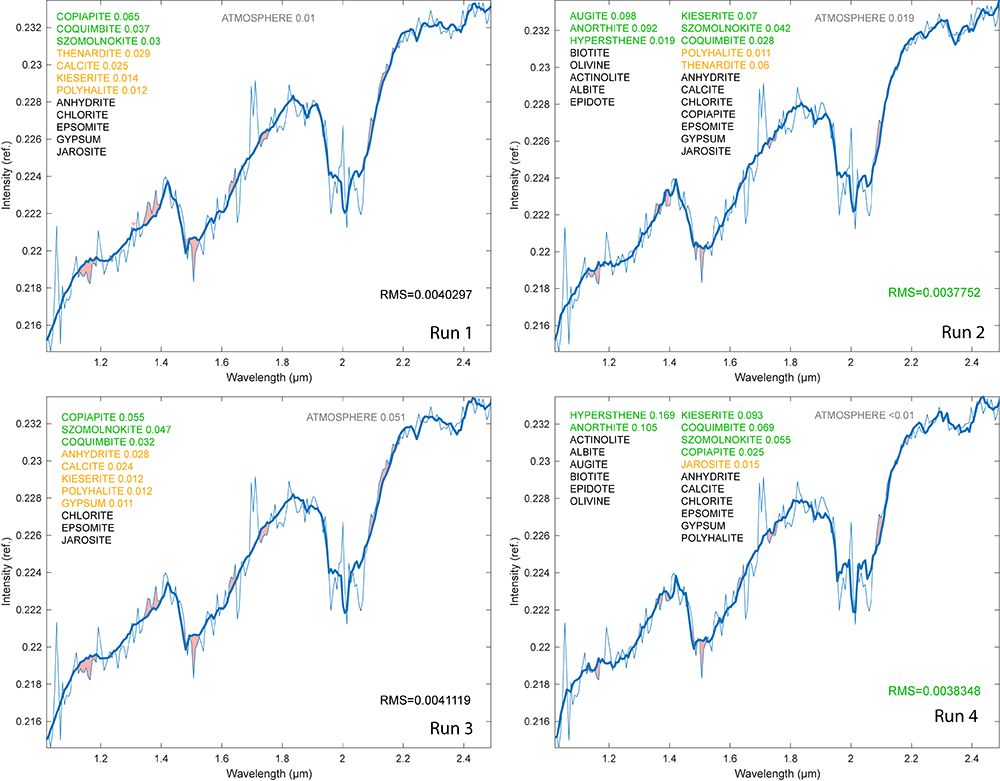

Capri Chasma is a canyon located at the exit of Valles Marineris. Its flanks are piled with lava flows. It also contains in places, bright Interior Layered Deposit (ILD) revealing a complex geological history. Some slopes are also the site of a phenomenon known as RSL (recurrent slope lineae). In the northern part of the Chasma, within the thickest portion of the Interior Layered Deposit (ILD), rock units are exposed along some walls, that are part of a ∼30-km circular depression. A well-preserved stratigraphy in the northwest-facing slope reveals several sulfate-rich units, including kieserite and poly-hydrated sulfates, some of which are associated with red and gray hematite [1,2]. A presumed impact has disrupted the southern stratigraphy, redistributing these mineral layers and contributing to a jumbled geological structure. The presence of sulfates and hematite suggests initial ILD deposition by evaporation of magnesium and sulfur-rich brines, followed by groundwater upwelling events that penetrated the ILD, allowed gray hematite precipitation, and induced diagenetic alteration. Alternative explanations involve atmospheric deposition of sulfur-rich aerosols and dust particles within the ice deposits followed by weathering and formation of the sulfates during Martian climatic cycles. As a result, the origin of the Capri Chasma ILDs is still rather vague, and more information needs to be gathered on the stratigraphy, morphology, and color of the deposits, as well as on the microtexture of the materials that make them up. In order to better understand the nature of the deposits and the conditions of their formation, our investigation is based on three types of data: (i) CTX and HiRISE digital terrain models refined by photoclinometry (ii) a multi-angle sequence of hyperspectral images acquired by the CRISM spectro-imager on which we invert Hapke's photometric model after atmospheric correction (iii) a series of images from the CaSSIS multispectral sensor on which photometric and atmospheric correction is performed to extract the intrinsic surface reflectance in four spectral bands, resulting in true color images.