EPSC Abstracts

Vol. 18, EPSC-DPS2025-1371, 2025, updated on 09 Jul 2025

https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1371

EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025

© Author(s) 2025. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Evolutionary constraints on the solar wind transition epoch and the duration of the terrestrial unmagnetized phase using lunar volatiles deposited from Earth's exosphere

- 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Rochester, Rochester, 14627, NY, United States of America (shubhonkar.paramanick@rochester.edu)

- 2Laboratory for Laser Energetics, University of Rochester, 250 E River Road, Rochester, 14623, NY, United States of America

- 3Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Rochester, Rochester, 14627, NY, United States of America

The occurrence of H, N, and light noble gases like He, Ne, and Ar in the lunar regolith—but not in lunar rocks—indicates that these volatiles likely have an extra-lunar origin. While the solar wind (SW) is known to implant ions on the lunar surface and contribute some volatiles, it does not fully explain the abundance of N or the variations in its isotopic composition (15N/14N). To account for this, Ozima et al. [1] proposed that Earth's atmosphere may have served as a source during a time when it lacked a geomagnetic field, allowing atmospheric particles to escape freely. Li et al. [2] connected lunar surface water to interactions with the SW when the Moon passed through this magnetotail, whereas Wang et al. [3] suggested the magnetospheric Earth wind (EW) as a potential exogenous source of lunar surface hydration. Similarly, Poppe et al. [4] observed terrestrial ions in Earth's magnetotail. However, these studies did not model how Earth's escaping atmosphere and the SW might have interacted or mixed with the planetary outflow.

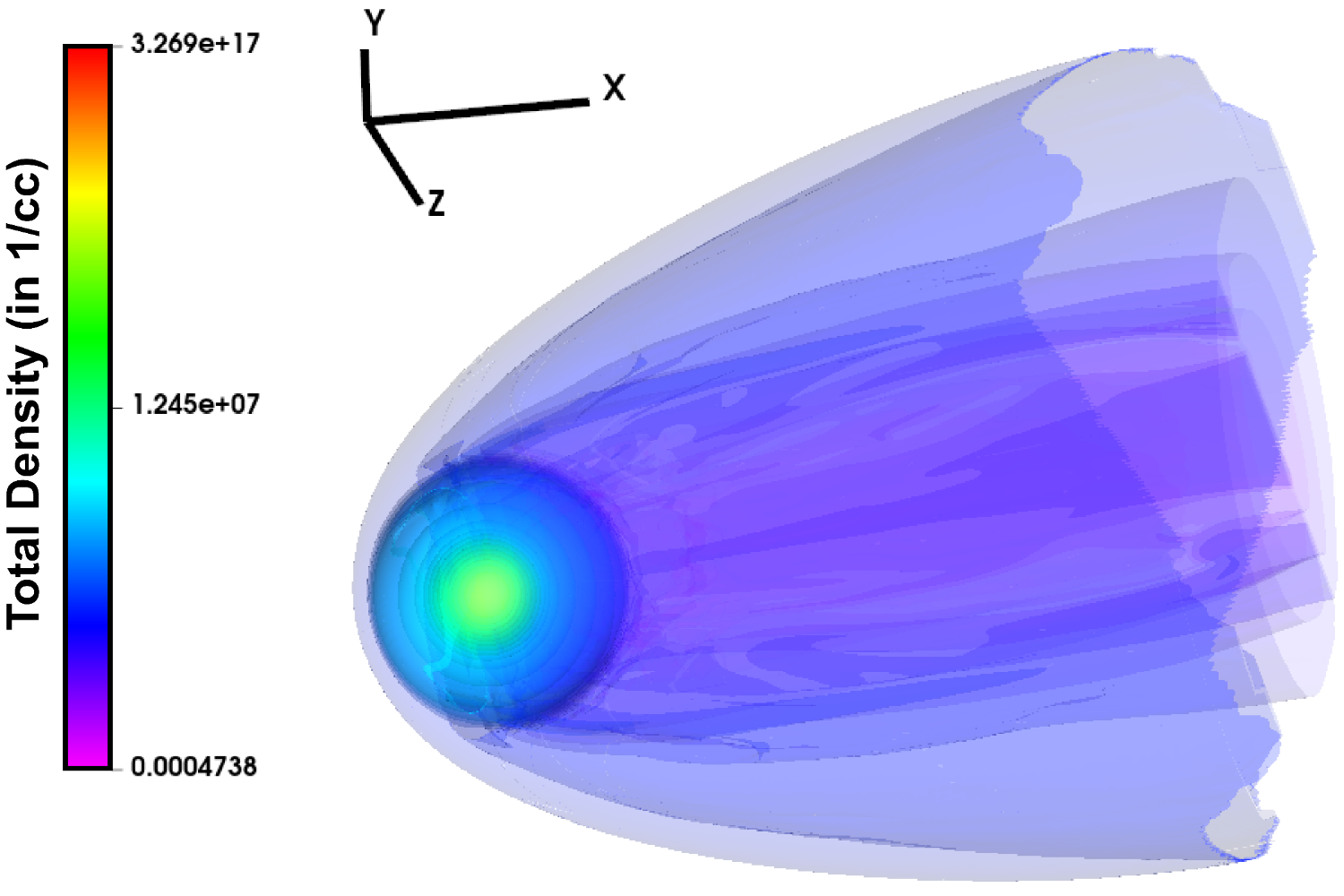

To explore this, our research [5] combines 3D magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) models developed using the AstroBEAR code with a terrestrial ionosphere model. This model simulates how particles from Earth's atmosphere might have reached the lunar surface during both magnetized and unmagnetized phases of Earth's history (Figure 1). Specifically, we assess the contribution of atmospheric and SW fluxes to the Moon by comparing scenarios where Earth either had or lacked a magnetic field. We incorporate solar XUV-driven atmospheric photoionization in our ionosphere models to represent both early (Eoarchean) and late Earth (contemporary) atmospheres to estimate the transport and deposition of volatile species on the lunar nearside. The simulations assume the Moon had no global magnetic field during the relevant period, consistent with paleomagnetic measurements [6].

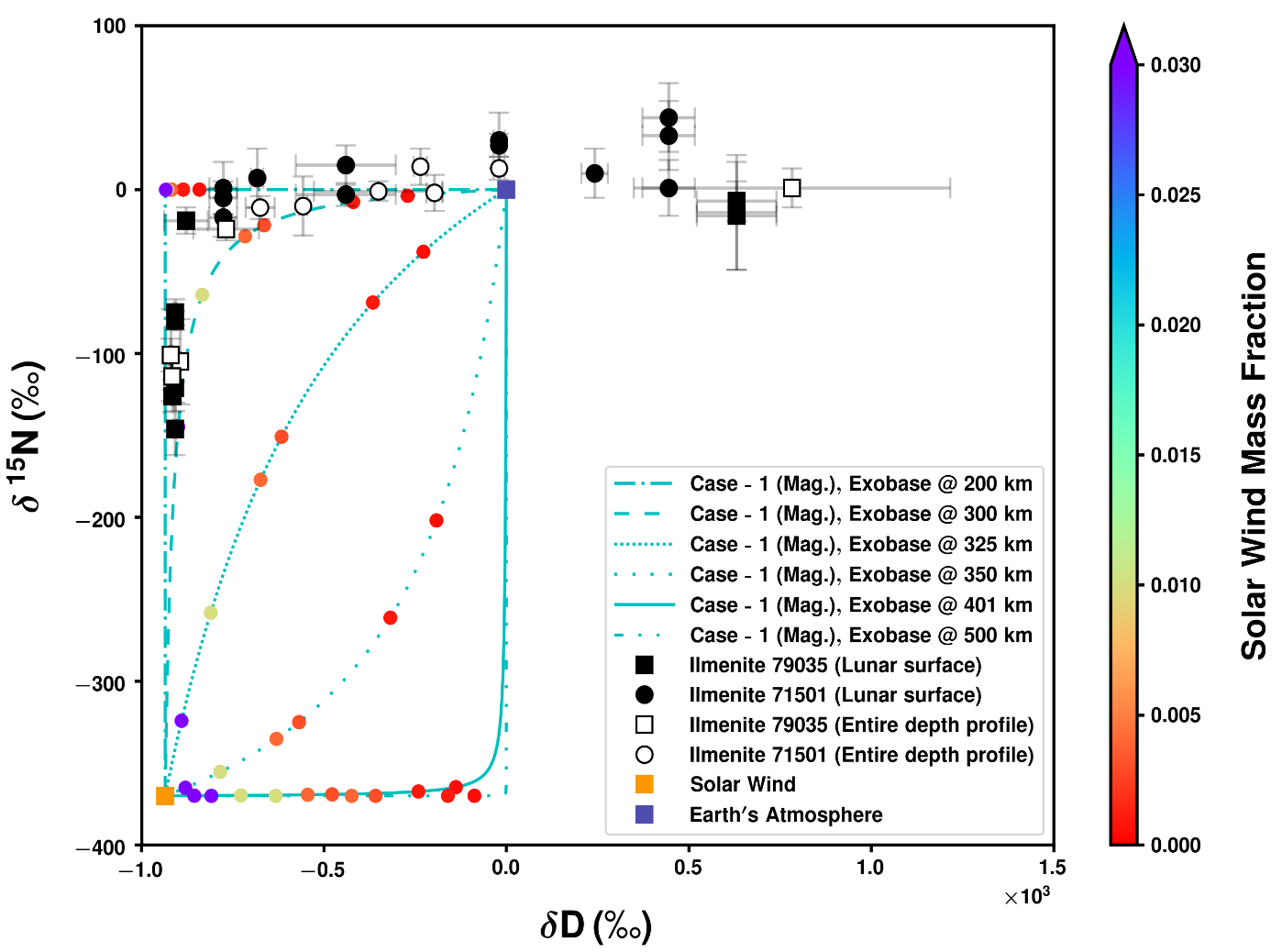

By analyzing the observed non-solar flux in the Apollo lunar samples and comparing these observations to our simulated EW flux data, we infer when Earth's geodynamo might have begun. We apply the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) technique to constrain the pairwise hydrodynamic exobase (PHE) during the period of volatile implantation for various combinations of isotope ratios in mixing diagrams.

Figure 1: 3D rendering of the MHD simulation of the outflows for the present-day Earth case.

We employ a binary mixing model that leverages distinct isotope ratios and elemental abundances to estimate the relative contributions of solar and non-solar components (NSC). When data align along a single curve, it indicates compatibility with that particular PHE altitude, regardless of the proportion of NSC (Figure 2). Our model explains the data when the EW flux exceeds the measured non-solar flux. For each species considered, we incorporate an early epoch without a geodynamo and strong SW, followed by a period where Earth possessed a dipolar field with a relatively weak SW.

Figure 2: δ15N-δD binary mixing diagram.

Key Results: We find that the average atmospheric flux from Earth to lunar soil remains comparable under both early unmagnetized and contemporary magnetized conditions. This is primarily due to the magnetic field modifying atmospheric density gradients, causing them to fall off as a power law with radial distance rather than exponentially. As a result, significant atmospheric mass persists at higher altitudes and can be transported by the SW. Nonetheless, during the early SW phase, characterized by elevated ram pressure and the absence of a geomagnetic field, the SW-to-EW flux ratio becomes large, rendering it insufficient to explain the volatile inventories observed in lunar soils. Instead, the dominant non-solar component in lunar samples is best attributed to long-term implantation facilitated by a sustained geodynamo, thus highlighting the competing effects of SW conditions and dynamo strengths.

To constrain the onset of Earth's magnetic field, we interpret the isotopic composition of lunar volatiles as a linear combination of contributions from both the unmagnetized early Earth and the later magnetized Earth, regardless of how minimal the early atmospheric contribution might have been for each element. This implies that only a brief period of geomagnetic inactivity can be accommodated.

We also conducted analyses with the Chamberlain atmosphere model. When the SW interacts with the exosphere, it sweeps all three populations, picking up from the upper atmosphere. We note that the dominant contribution to the Chamberlain profiles closely resembles the barometric profile we use for the Archean case; therefore, the atmospheric surface density and the plasmapause boundary do not alter substantively.

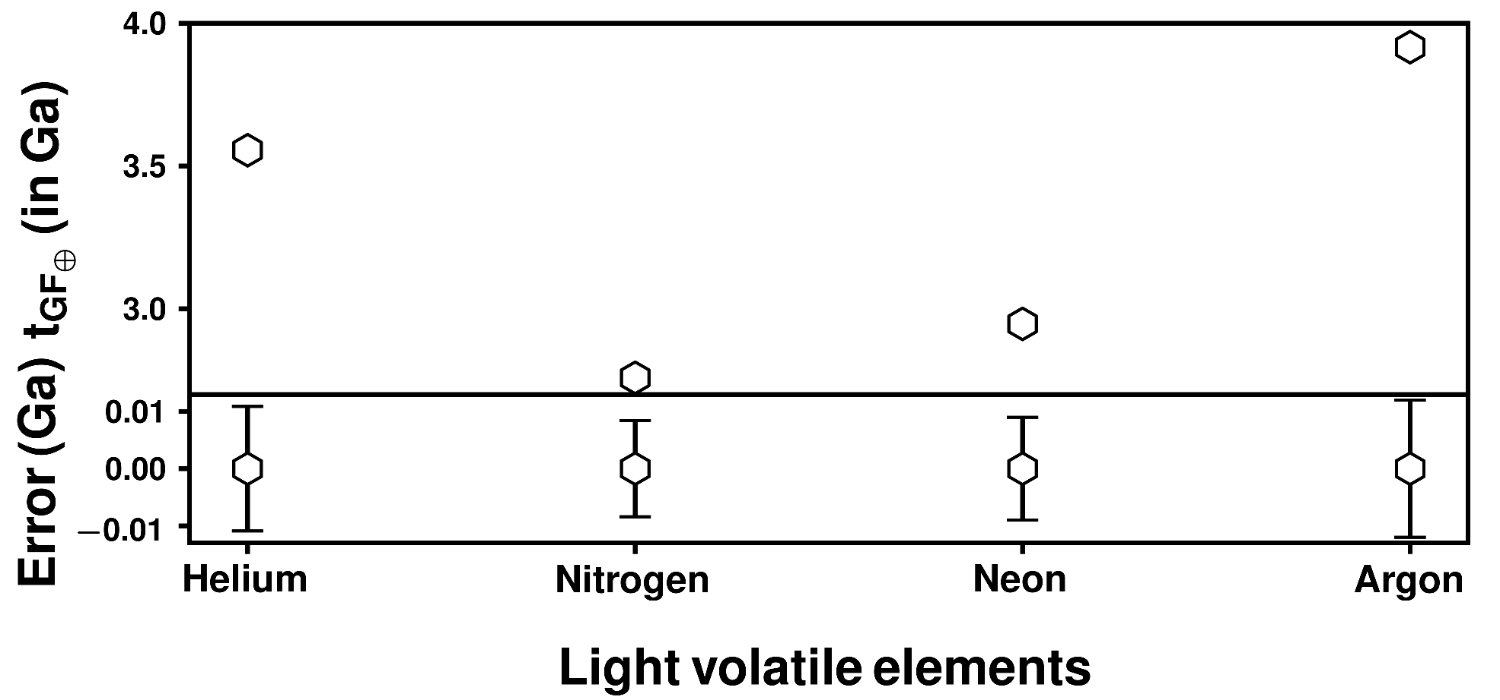

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that, except for hydrogen, the volatiles in lunar soil can be explained by EW from a magnetized Earth under current SW conditions. Among them, Ar imposes the most stringent constraint on how long Earth could have been unmagnetized, such that its presence in lunar soil is still explainable by an atmospheric source from Earth. We also decouple the strong-to-weak transition of the SW from the onset of the geodynamo by conducting simulation runs for a hypothetical early magnetized case. Based on our model, if these volatiles have a terrestrial origin, this points to Earth's geomagnetic field existing as early as 3.9 billion years ago (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Minimum geodynamo ages estimated from the terrestrial flux of different species.

References:

[1] Ozima et al., Nature, 2005;

[2] Li et al., Nat. Astron., 2023;

[3] Wang et al., APJ, 2024;

[4] Poppe et al., Planet. Sci., 2021;

[5] Paramanick et al., arXiv, 2024;

[6] Tarduno et al., Sci. Adv., 2021.

How to cite: Paramanick, S., Blackman, E. G., and Tarduno, J. A.: Evolutionary constraints on the solar wind transition epoch and the duration of the terrestrial unmagnetized phase using lunar volatiles deposited from Earth's exosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1371, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1371, 2025.