- 1Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, UK (danielle.kallenborn20@imperial.ac.uk)

- 2Lunar and Planetary Institute (USRA), Houston, TX

- 3Université Paris Cité, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, CNRS, Paris, France

Introduction:

Numerical impact simulations and laboratory experiments often only focus on vertical impacts in homogeneously layered targets. Most impacts, however, occur at an oblique angle (< 90° to the horizontal), with the most likely angle being 45° [1]. Planetary surfaces either have active land-forming processes or are heavily cratered, both of which introduce further complexity to impact processes in the form of pre-existing topography and variations in sub-surface structure. Previous studies have shown that both impact angle [e.g., 2] and target heterogeneities [e.g., 3] play a significant role in crater formation, causing asymmetries in the final crater morphology, central uplift and ejecta distribution. We are conducting a systematic 3D numerical study to investigate the complex interplay of pre-existing topography, changes in crustal thickness, and impact angle and azimuth. To constrain the parameter space and demonstrate potential applications of this investigation, we present a case study on the Schrödinger basin impact event. The ~320 km lunar peak ring basin shows several asymmetries that have been attributed to both target heterogeneity [4, 5] and an oblique impact [6].

Methods:

We use the iSALE3D shock physics code [7, 8] to numerically model crater formation in a variety of heterogeneous targets and for a range of impact azimuths and angles.

For the Schrödinger basin, we assume a pre-impact terrain dominated by the influences of SPA with an eastward sloping topography and crustal thinning from 40 to 20 km. We choose target and impactor parameters based on successful 2D simulations [5]. Granite and dunite, which are the best available material analogues, were used to describe the crust and mantle. For computational expediency the impactor is represented by the same material model as the crust, implying an impactor density of 2650 kg/m3. We use a 25 km-diameter impactor and collisional speed is increased for oblique angles to preserve a vertical velocity component of 15 km/s. To produce a crater in the centre of the layered setup, the point of impact is offset by 40 and 50 km in the 45°- and 30°-degree scenarios, respectively. We use the “block model” for acoustic fluidization to facilitate late-stage collapse [9]. The Schrödinger simulations have a resolution of 1250 m (10 cells per projectile radius). We compare our results to LOLA topography [10] and GRAIL crustal thickness data [11].

Schrödinger Case Study - Results and Discussion:

Sloping Topography and Changes in Crustal Thickness.

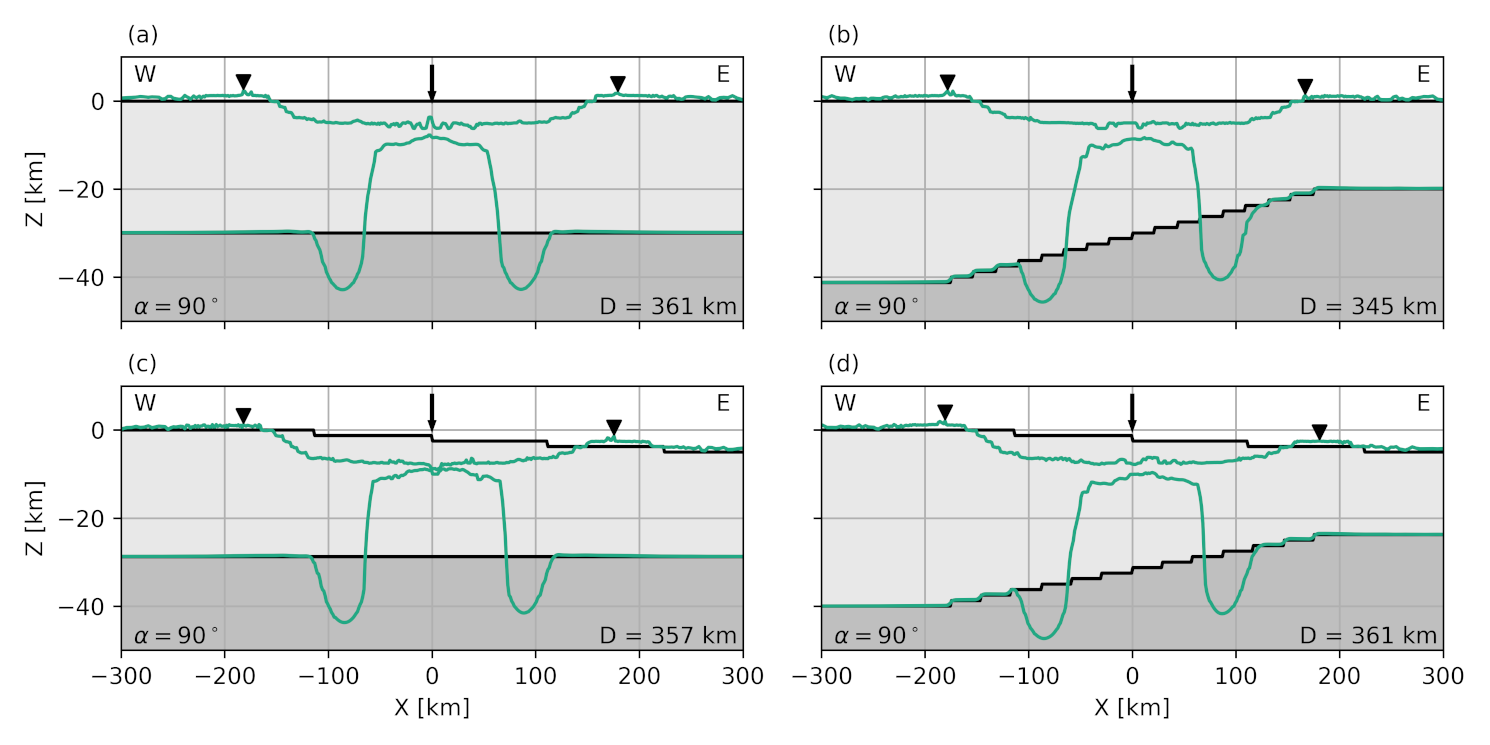

Figure 1. Vertical impact into (a) horizontal layers, (b) flat surface topography and thinning crust, (c) sloping surface topography and flat crust-mantle interface, and (d) sloping surface topography and thinning crust. Simulation results, overlying the pre-impact crust (light grey) and mantle (grey).

Sloping topography and changes in crustal thickness below the pre-impact surface cause asymmetry in the shape of the final crater and central uplift (Fig. 1). Simulations that include the eastward sloping topography produce higher and steeper crater walls in the west, consistent with observed LOLA topography. While absolute basin depths are greater for these simulations (~ 6km), relative depths (i.e. the difference between the post- and pre-impact surface) stay largely consistent across all simulations (4.25 to 4.5 km) and align with the observed average depth of the Schrödinger basin (4.5 km) [4]. Final basin diameter, which scales with the mass and velocity of the impactor [12], is independent of the pre-impact layer setup.

Impact Angle and Azimuth.

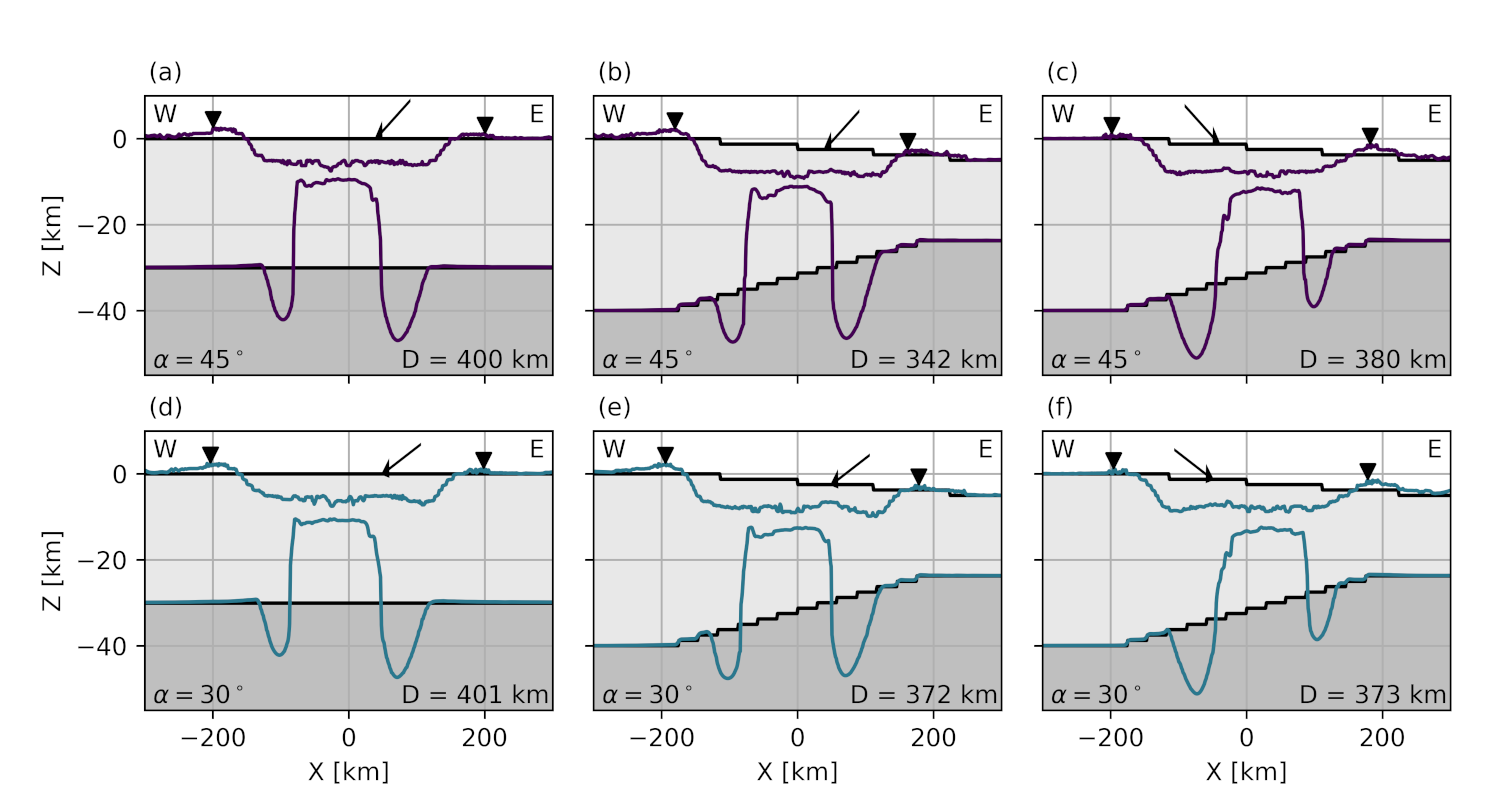

Figure 2. Oblique impacts (45° and 30°) into a homogeneously layered target (left), and into a heterogeneous target with an east to west (middle) and west to east (right) impact azimuth.

Oblique impacts in a flat, constant crustal thickness target produce asymmetry both in the final surface topography and in the central uplift with a wider and deeper annular bulge in the uprange direction (Fig. 2). In a heterogeneous target, there is an interplay between impact azimuth and target effects. The effect of crustal thinning seems to be offset by the effect of oblique impact in the east to west impact scenario, while the impact trajectory enhances asymmetries introduced by target heterogeneity in the west to east impact. Overall, final craters are larger than in a vertical impact, suggesting that the scaling of crater dimensions might be more complex than assumed.

Based on our results, the almost absent crater rim in the south and the higher and steeper crater walls in the west observed in LOLA topography, could support the scenario of an oblique impact from south-east to north-west [6]. A more comprehensive analysis of crustal thickness below the basin will provide more insights into the crater’s formation.

Conclusions:

The Schrödinger case study shows that even subtle variations in target heterogeneity and impact trajectory can produce asymmetries in final crater structure. Modelling impact craters of scientific interest in a more realistic context will lead to a better understanding of the pre- and post-impact distribution of materials and crater formation processes.

Our ongoing 3D numerical study will explore a wide range of impact scenarios to systematically investigate and disentangle the complex interplay of target heterogeneity and impact trajectory.

Acknowledgments: We gratefully acknowledge the developers of iSALE. We thank Caroline Chalumeau whose MSci project provided the inspiration for the work presented here.

References:

[1] Shoemaker, E. M. (1961). Phys. and Astron. of the Moon, 283–359. [2] Davison, T. M., & Collins, G. S. (2022). Geophys. Res. Letters, 49(21), e2022GL101117. [3] Aschauer, J., & Kenkmann, T. (2017). Icarus, 290, 89–95. [4] Kramer G. Y. et al. (2013) Icarus, 223(1), 131–148. [5] Kring D. A. et al. (2016) Nature Comm., 7(1), 13161. [6] Kring, D. A. et al. (2025) Nature Comm., 16(1), 1–7. [7] Elbeshausen D. et al. (2009) Icarus, 204(2), 716–731. [8] Elbeshausen D. and Wünnemann K. (2011) Proc. 11th Hypervel. Impact Symp., Vol. 4, 287-301. [9] Wünnemann K. and Ivanov B. A. (2003). Planet. Space Sci., 51, 831–845. [10] Smith D. et al. (2010). Geophys. Res. Letters, 37(18). [11] Wieczorek M. A. et al. (2013) Science, 339(6120), 671–675. [12] Holsapple, K. A. (1993). Rev. of Earth and Planet. Sci., Vol. 21, 333–373.

How to cite: Kallenborn, D. P., Collins, G. S., Davison, T. M., Kring, D. A., and Wieczorek, M. A.: Three-Dimensional Numerical Impact Simulations of Crater Formation in Heterogeneous Targets, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1373, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1373, 2025.