- 1INAF, IAPS, Rome, Italy (michelangelo.formisano@inaf.it)

- 2Department of Mathematics and Physics, University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli", Viale Lincoln 5, Caserta (Italy)

- 3INAF-Astronomical Observatory of Padova, Vicolo dell'Osservatorio 5, Padova (Italy)

- 4Department of Physics, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Via della Ricerca Scientifica 1, Rome (Italy)

Introduction

Using the Moon as a case study, we investigate how small-scale surface roughness influences the thermal behavior of airless planetary bodies through self-heating effects. Indirect solar radiation, reflected and scattered by rough terrain, can warm otherwise shaded regions, particularly in highly irregular surfaces or concave topographies such as craters. This process can raise local temperatures by several kelvin, potentially affecting the stability of surface ices in micro cold traps. Our numerical model (e.g. [1]) accounts for both vertical and lateral heat exchange and simulates various rough surface configurations representative of lunar polar regions. We provide temperature maps, quantify self-heating contributions, and estimate the persistence of volatiles. These results may inform Lagrangian models (e.g., SPH codes) aimed at simulating volatile transport and exosphere formation [2].

Numerical Modeling

Before applying our 3D FEM model (e.g., [1]) using COMSOL Multiphysics, we generate synthetic rough surfaces with average slopes consistent with lunar surface roughness estimates found in the literature [3]. We produce eight terrains with mean slopes ranging from 2.5° (nearly flat terrain) to 40° (very rough surface). The method used to synthesize these surfaces is based on a sum of trigonometric functions, similar to a Fourier series expansion, where each term represents a specific spatial frequency of oscillation. In Fig.1, we show two of the synthetic surfaces: the left panels display the surface with a mean slope of 20°, while the right panels show the surface with a mean slope of 40°. The numerical code used to compute surface temperature accounts for both direct and indirect solar radiation, the latter known as self-heating. For these simulations, we arbitrarily choose a latitude of 80°, a heliocentric distance of 1 AU, and a global thermal inertia of 100 TIU.

Preliminary Results And Conclusions

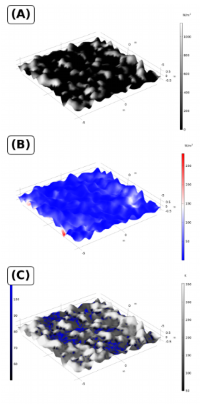

For each of the analyzed surfaces, we produced maps of surface temperature, direct solar illumination, and indirect illumination (due to self-heating), as shown in Fig.2. The threshold temperature adopted to assess the stability of water ice is 110 K, corresponding to a sublimation rate of approximately 100 kg/(Gyr m2 ), and thus to a survival timescale consistent with the age of the Solar System. Our preliminary results suggest the existence of a threshold mean slope-around 20°-that separates two distinct regimes. At low slopes (0-20°), shadowing dominates over self-heating, enabling the formation of cold traps [4]. In contrast, at higher slopes (>20°), self-heating becomes the dominant effect, hindering the preservation of water ice. The set of scenarios developed in this work will be further refined to provide a useful dataset for various planetary contexts.

Figure 1: Examples of the analyzed surfaces: the left panels present the case with a mean slope of 20°, while the right panels show the case with a mean slope of 40°.

Figure 2: Case 1: (A) Incoming flux from direct solar illumination; (B) Incoming flux from indirect illumination due to self-heating of the terrain; (C) Surface temperature map: the blue color scale is limited at 110 K-the stability threshold for cold traps-to emphasize areas where cold traps may be present. The selected time corresponds to local noon.

References

[1] Formisano M., et al., 2024, Planetary and Space Science, 251, 105969

[2] Teodori M., et al., 2025, Icarus (under review).

[3] Helfestein P. & Shepard M. K., 1999, Icarus, 141, 107

[4] Hayne P. et al., 2017, JGR Planets, 122, 2371.

How to cite: Formisano, M., Raponi, A., Teodori, M., Bertoli, S., Ciarniello, M., De Angelis, S., De Sanctis, M. C., Filacchione, G., Frigeri, A., Maggioni, L., and Magni, G.: Thermal Role of Self-Heating and Surface Roughness in Micro Cold Trap Stability at the Lunar Poles, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1411, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1411, 2025.