- Institut für Planetologie, Universität Münster, Wilhelm-Klemm-Str. 10, 48149 Münster, Germany (christian.schuckart@uni-muenster.de)

Context

The number of spacecrafts investigating small bodies and carrying remote sensing instruments for thermal infrared measurements has been steadily increasing. With the TIRI instrument - a thermal infrared imager - aboard the Hera mission as the latest example [1], there is and will be a wealth of data to interpret using thermophysical models. These models, when combined with mission data, enable the retrieval of key surface characteristics such as thermal conductivity, density, porosity, and grain size. The observation of new small bodies brings new demands on model accuracy, necessitating ongoing improvements to ensure robust, body-specific data analysis. A recent case highlighting this need is the TIR instrument, the predecessor to TIRI, aboard the Hayabusa2 mission. TIR was used to collect thermal maps of the asteroid Ryugu at various stages of the mission, prompting refinements in modelling approaches to match the complexity and specificity of the collected data. Previous findings have shown that a global thermophysical model without surface roughness could not reproduce the thermal measurements from TIR [3, 4]. A combination of a global scale thermophysical model with an adequate surface roughness description was identified as a crucial step toward accurately characterizing Ryugu’s surface thermal environment. Consequently, the next generation of thermophysical models will need to be highly adaptable, enabling the rapid incorporation of new findings and observational data.

Current implementation

We have developed for the purpose of solving the heat transfer equation for dry, airless planetary surfaces. At the core, MoCSI is a one-dimensional finite element method code, which can in principal run on a variety of geometries. In its current form, MoCSI can solve the heat transfer equation on each facet of any given shape model. What sets MoCSI apart from other thermophysical models is its highly modular architecture, which allows for easy adaptation to different applications and planetary bodies. Key physical properties – such as thermal conductivity, heat capacity, and density are managed by independent modules. This modular structure makes it straightforward to incorporate new or alternative formulations of physical parameters or mechanisms ensuring flexibility and extensibility. Already implemented modules are:

- Physical properties such as density, heat capacity and thermal conductivity, specifically for regolith [5] and porous boulders [6]

- A ray-caster and the solution of the radiosity equations [7]

- Integration of SPICE [8]

These currently available modules allow for a thorough investigation of the thermal surface environment of asteroids.

Verification

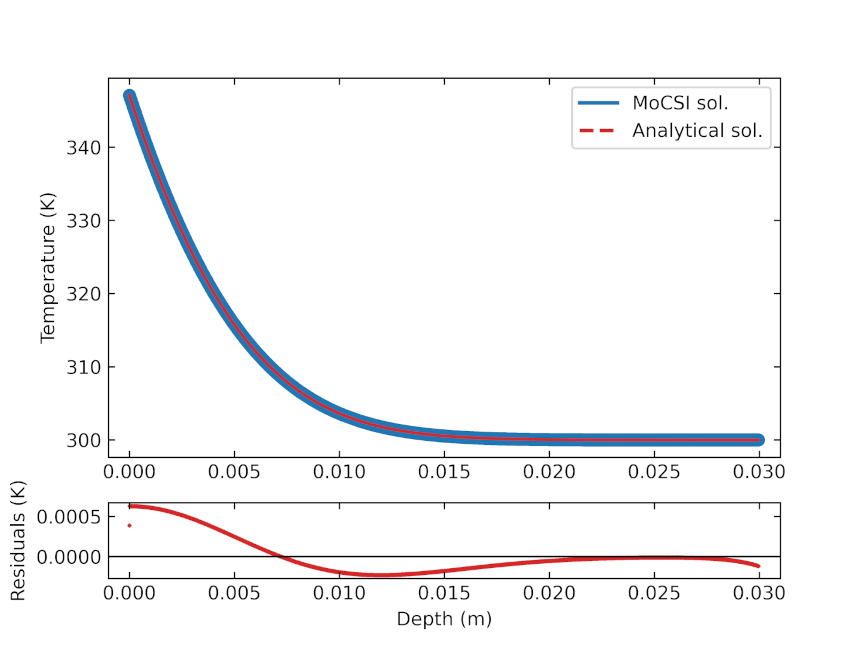

Fig. 1: MoCSI solver comparison against the known analytical solution of a semi-infinite domain with constant heat diffusivity and constant incoming heat flux. Temperatures (top panel) and temperature residuals (bottom panel) of MoCSI and the analytical solution are shown as a function of depth.

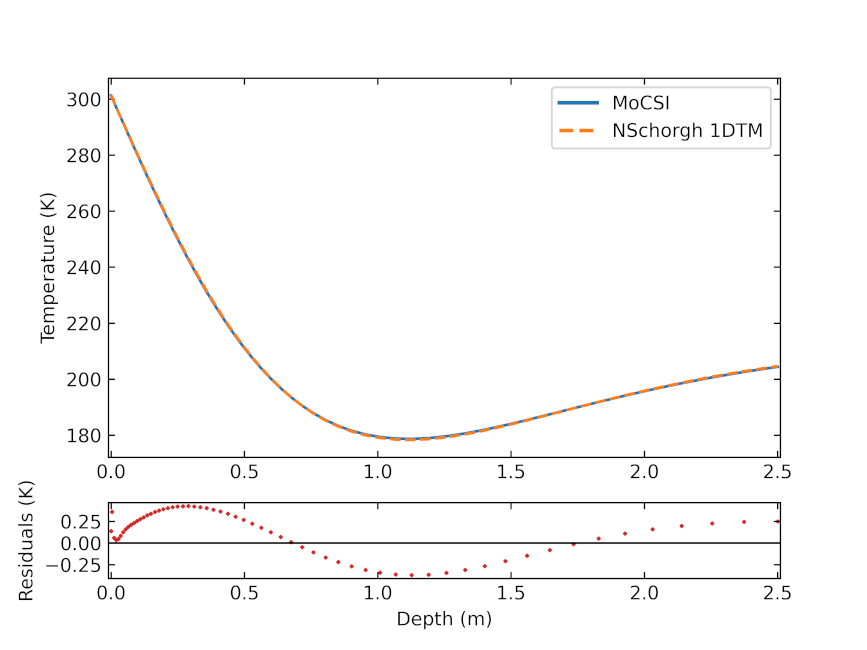

Fig. 2: Comparison of MoCSI and the ‘’testcrankQ`` case defined for 1DTM [11]. Temperatures (top panel) and temperature residuals (bottom panel) of MoCSI and the Norbert Schörghofer model [9] shown as a function of depth. The minor (agree to the first decimal place) differences are due too different implementations of the surface energy balance upper boundary condition.

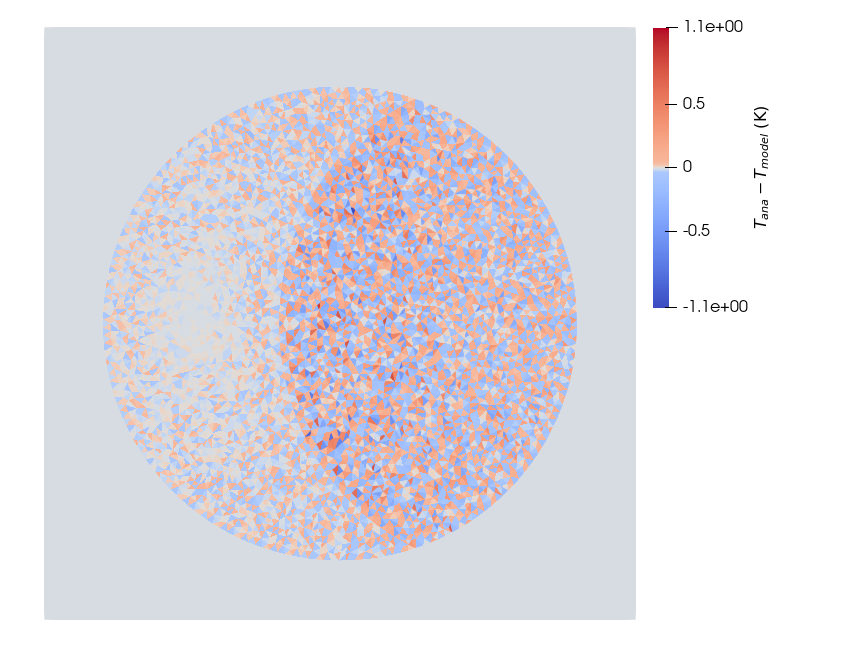

Fig 3: Comparison of the radiosity module in MoCSI against the known analytical solution of the surface temperature of a partially shadowed spherical crater presented in [7] with the geometry of [5]. Shown are the temperature residuals between MoCSI and the analytical solution in a top down view onto the crater.

MoCSI’s currently implemented TDMA (Tridiagonal Matrix Algorithm) solver has been verified against known analytical solutions of the heat transfer equation (Figure 1) and against the 1DTM code of Norbert Schörghofer [9] (Figure 2). We use an analytical solution for the radiosity in a spherical crater to verify the implementation of the radiosity equations [10]. As shown in Figure 3, MoCSI’s results closely match the expected values, consistent with findings in [7]. Further results, including applications of MoCSI to selected craters on Ryugu are forthcoming.

References

[1] Okada, T. et al. (2024), LPSC 2024, #1777.

[2] Okada, T. et al. (2020), Nature 579, pp. 518–522.

[3] Shimaki, Y. et al. (2020), Icarus 348, 113835.

[4] Senshu, H. et al. (2022), Int J Thermophys 43, 102.

[5] Gundlach, B. and Blum, J. (2012), Icarus 219, 618.

[6] Maxwell, J.C. (1873), Clarendon Press 2, 3408.

[7] Potter, S.F. et al. (2023), Journal of Computational Physics: X 17, 100130.

[8] Acton, C.H. (1996), Planetary and Space Science 44 No. 1, pp. 65-70.

[9] Schörghofer, N. and Khatiwala, S. (2024), Planet. Sci. J. 5, 120

[10] Ingersoll, A.P. et al. (1992), Icarus 100, pp. 40-47.

[11] Schörghofer, N. (2025), Planetary Code Collection, Github.

How to cite: Schuckart, C., Aussel, B., Rückriemen-Bez, T., Güttler, C., and Gundlach, B.: Modular heat transfer code for dry, airless planetary surfaces: MoCSI, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1426, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1426, 2025.