- 1School of Earth Sciences, Wills Memorial Building, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, UK (matthew.roche@bristol.ac.uk)

- 2School of Physics, HH Wills Physics Laboratory, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TL, UK

- 3NASA Ames Research Centre, MS 245-3, Moffett Field, CA 94035, USA

Introduction: How the Earth and other terrestrial planets acquire their volatile element budgets (e.g., N, C, H, noble gases) remains a fundamental unanswered question. Large fractions of planetary volatiles are believed to have been acquired during the main stages of accretion (e.g., Halliday 2013; Marty 2012; Mukhopadhyay & Parai 2019). Therefore, the atmospheres and oceans of the planetary embryos from which terrestrial planets are built must have survived the giant impact phase – a period dominated by collisions between planet-sized bodies – for those volatiles to be retained to this day. Accurately quantifying how much atmosphere is lost in different styles of impact and by what mechanisms is key to gaining a better understanding of the volatile evolution of planets.

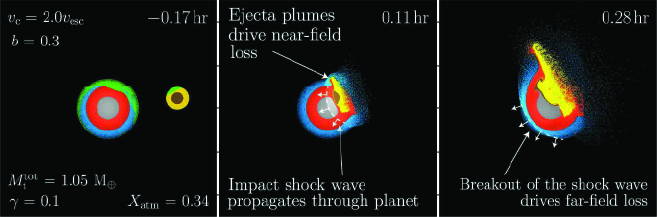

Early studies (e.g., Ahrens 1990; Melosh & Vickery 1989; Ahrens & O'Keefe 1987; Vickery & Melosh 1990) suggested that atmospheric loss during giant impacts can be driven primarily by air shocks, ejecta plumes, and shock-kick. Recent advances in numerical techniques have allowed such processes to be captured simultaneously in high-resolution 3D smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) simulations (e.g., Kegerreis et al. 2020a,b; Denman et al. 2020, 2022), and have allowed scaling laws to be produced that can predict the expected loss outcome for a given set of impact parameters. However, these previous studies did not explore in detail the relative contributions of the different mechanisms driving loss and how they varied with impact parameters and atmospheric properties, which can lead to significant errors in the loss predicted by existing scaling laws (e.g., Kegerreis et al. 2020b).

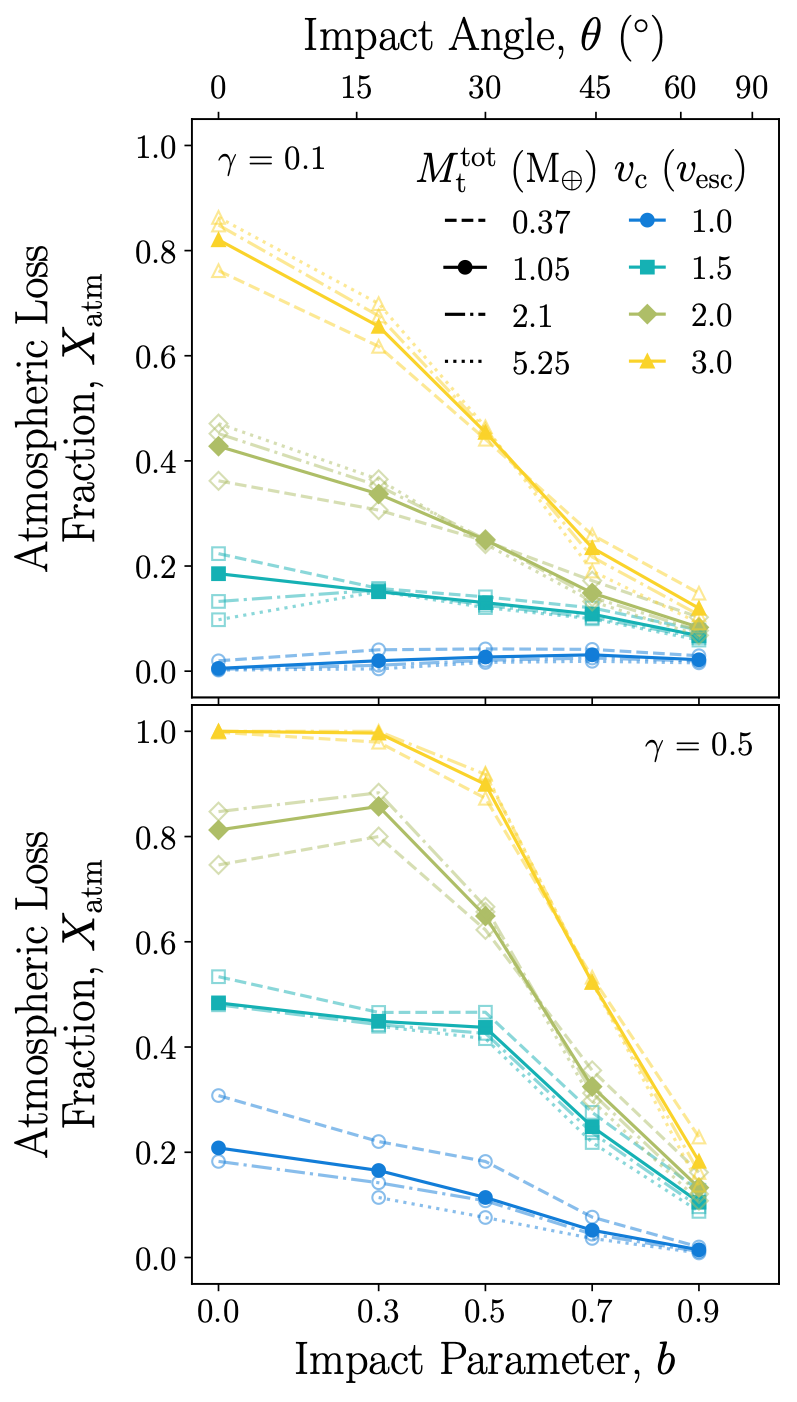

The mechanisms of atmospheric loss: We conducted a suite of SPH giant impact simulations of collisions onto planets between 0.35–5.0 Earth masses (M⊕) with 5% mass fraction H2–He atmospheres. We de-convolve the total atmospheric loss (Fig.1) into its near- and far-field components and show conclusively that atmospheric loss is principally controlled by different mechanisms depending on location relative to the impact – ejecta plumes and air shocks in the near field and shock-kick in the far field (Fig.2). By parameterising these mechanisms independently, we derive a new scaling law that accurately approximates atmospheric loss and can readily be incorporated into models of volatile accretion during planet formation.

Figure 1: Atmospheric loss fraction as a function of impact parameter for different target planet masses (line style), mass ratios (panels), and velocities (colours/shapes) (Roche et al. 2025).

Figure 2: Illustrative time snapshots from an example SPH giant impact simulation with a resolution of 106 particles (Roche et al. 2025).

Predicting loss from 1D–3D coupling: Lock & Stewart (2024) showed that hotter, lower mean molecular weight, and lower pressure atmospheres are much more easily lost during giant impacts. Such atmospheres can be difficult to model using SPH simulations due to the lack of high-quality, publicly available equations of state and the extremely high numerical resolutions required to model thin atmospheres. Here we investigate whether atmospheric loss can be predicted by combining the results of 3D simulations with less computationally expensive 1D calculations to help overcome these limitations.

Atmospheric loss due to shock-kick has previously been investigated using 1D hydrodynamic simulations (Genda & Abe 2003, 2005; Lock & Stewart 2024), and comparisons made to the loss calculated from SPH simulations (Genda & Abe 2003; Kegerreis et al. 2020a). We improve upon this previous work and calculate the far-field loss that would be predicted from coupling the shock field from our SPH simulations with 1D impedance match calculations of loss from shock-kick (Lock & Stewart 2024).

We find excellent agreement between the 3D and coupled 1D–3D calculations (Fig.3), meaning that ground pressures sampled from existing SPH simulations can be used to make first order approximations of loss for a given impact without needing to run additional high resolution SPH simulations.

Figure 3: Mollweide projections of far-field loss fraction (upper hemisphere) from 3D SPH simulations and the far-field loss fraction predicted by coupled 1D–3D calculations (lower hemisphere) (Roche et al. 2025).

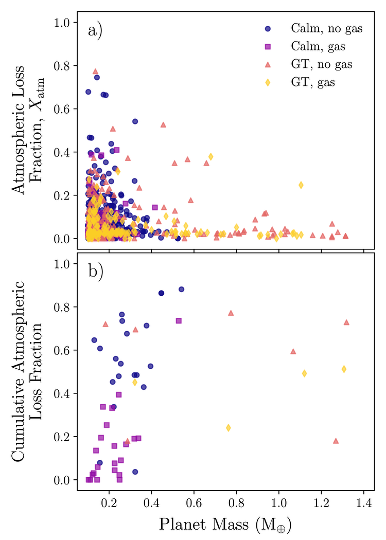

Implications for the volatile evolution of planets: We apply our new scaling law to the results from existing N-body simulations of solar system formation (Carter et al. 2015; Carter & Stewart 2022) to gain insight into the role that loss during giant impacts could play in the volatile evolution of planets (Fig.4). We find that individual loss events that substantially change atmosphere mass fraction (by >10%) are not uncommon for small planet masses (<0.6 M⊕) but are generally rare for larger planet masses (>0.8 M⊕). Despite this, the cumulative effect of multiple giant impacts during accretion can lead to much greater atmospheric loss (40–70%) for planets approaching ~1.0 M⊕ with an initial 5% mass fraction H2–He atmosphere. Given that we have neglected the fact that lower pressure atmospheres are more easily eroded (Lock & Stewart 2024) and have also not considered the presence of surface oceans which are known to strongly control atmospheric loss (Genda & Abe 2005; Lock & Stewart 2024), these results represent a lower limit and likely a significant underestimate of the amount of loss driven by giant impacts during accretion. Giant impacts therefore likely play a key role in controlling the volatile budgets of planets.

Figure 4: Atmospheric loss fraction experienced from individual giant impacts (a) and the combined effect of loss through accretion (b) in N-body simulations for four different solar system formation scenarios (colours/shapes) (Roche et al. 2025).

Conclusion: We have gained critical insight into the mechanisms of atmospheric loss during giant impacts which has allowed us to develop new tools for better understanding the role of giant impacts in the volatile evolution of planets. Our results suggest that atmospheric loss due to giant impacts plays a considerable cumulative role in shaping the volatile budgets of terrestrial planets. Future work will seek to quantify differences in the efficiency of atmospheric loss depending on the atmospheric and surface properties, as well as quantifying the delivery of volatiles by the impactor as well as the target.

How to cite: Roche, M., Lock, S., Dou, J., Carter, P., Kegerreis, J., and Leinhardt, Z.: Atmospheric loss during giant impacts: mechanisms and scaling of near- and far-field loss, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1501, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1501, 2025.