EXOA13

Bridging geosciences and astronomy to interpret rocky (exo)planet observations

Convener:

Rob Spaargaren

|

Co-conveners:

Claire Guimond,

Maggie Thompson,

Oliver Herbort,

Linn Boldt-Christmas,

Philipp Baumeister,

Yamila Miguel

Orals THU-OB2

|

Thu, 11 Sep, 09:30–10:30 (EEST) Room Mars (Veranda 1)

Orals THU-OB6

|

Thu, 11 Sep, 16:30–18:00 (EEST) Room Mercury (Veranda 4)

Posters THU-POS

|

Attendance Thu, 11 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Thu, 11 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Finlandia Hall foyer, F211–220

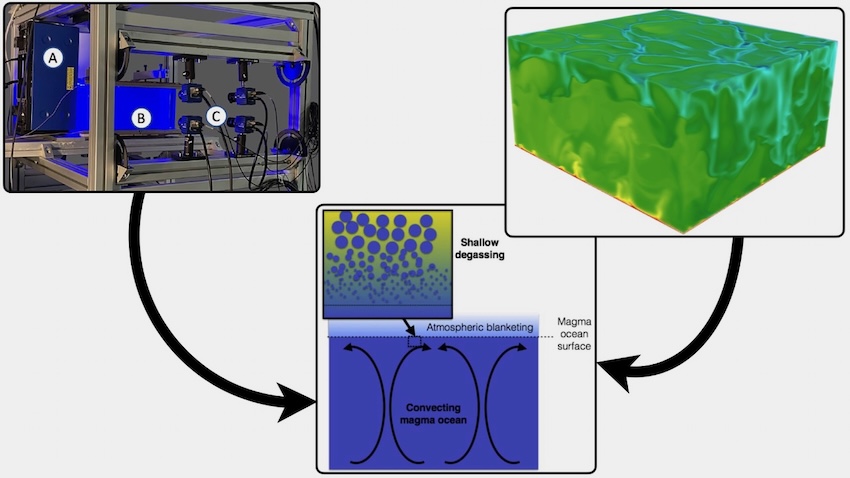

Rocky planet atmospheres and surfaces form and evolve under close interaction with their deeper interiors. Whether a planet has formed an atmosphere by volatile exchange with a magma ocean, by volcanic outgassing, or lost its atmosphere completely, understanding its observed state requires knowledge of interconnected processes operating across a wide range of spatial and temporal scales. Processes governing atmospheric evolution, and how it interacts with the interior, include volcanism, weathering, tectonics, magnetic field generation, interior and atmospheric volatile chemistry, and atmospheric loss. These processes operate on various timescales, from rapid magma-atmosphere equilibration, to the shaping of tectonics on the early Earth, to long-term climate feedbacks that sustain temperate conditions on planets like Earth. Studying these interactions - both in the Solar System and beyond - demands a fundamentally multidisciplinary understanding of rocky planets, spanning astronomy, geosciences, and planetary sciences.

This session aims to bring together scientists from astronomy, geosciences, and planetary sciences, to explore how interior-atmosphere interaction shapes rocky (exo)planet surfaces and atmospheres. We welcome contributions spanning experimental work, observational efforts, and modelling studies. By combining insights from exoplanets, which serve as a natural laboratory for rocky world diversity, and Solar System planets, which provide the detailed observations needed to build and validate models, we can develop a robust framework for interpreting observations of any rocky body. We encourage discussions that span all related fields, fostering new collaborative approaches to studying rocky planet evolution.

Session assets

09:30–09:33

Introduction

09:33–09:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-2075

|

solicited

|

On-site presentation

09:48–10:00

|

EPSC-DPS2025-948

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

10:00–10:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-634

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

10:12–10:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1473

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

10:24–10:30

Discussion

16:30–16:45

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1501

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

16:57–17:09

|

EPSC-DPS2025-448

|

Virtual presentation

17:21–17:33

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1568

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

17:33–17:45

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1896

|

On-site presentation

17:45–17:57

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1929

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

17:57–18:00

Discussion

F212

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1372

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F213

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1739

|

Virtual presentation

F214

|

EPSC-DPS2025-210

|

On-site presentation

F215

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1536

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F217

|

EPSC-DPS2025-465

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F218

|

EPSC-DPS2025-196

|

On-site presentation

F219

|

EPSC-DPS2025-747

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F220

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1323

|

ECP

|

Virtual presentation