- 1INAF, Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome, Italy (salvatore.buoninfante@inaf.it)

- 2Institut de physique du globe de Paris, Université Paris Cité, CNRS, Paris, France

- 3DiSTAR, Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II”, Naples, Italy

Introduction:

Impact basins on terrestrial planets are the result of the intense and widespread impact events that affected the planetary bodies, usually recognized and studied through satellite images, topographic and gravity data.

Peak-ring and multi-ring basins have been deeply investigated in the last decades. While peak-ring basins are characterized by a rim crest and an interior peak ring, multi-ring basins are larger and characterized by additional concentric topographic rings (e.g., [1]).

Un updated catalog of such impact basins on the Moon was already provided by Neumann et al. [2]. They analyzed GRAIL data to show that large lunar basins are characterized by a central gravitational anomaly. The size of this gravitational anomaly is comparable to the diameter of the inner peak-ring of a basin, while the main ring is approximatively twice the diameter of the peak ring [2]. This work confirmed the existence of previously proposed basins, provided the size of inner ring and main rim structures, and allowed detecting new basins that were not yet identified.

For Mars, complete catalogs of the Martian impact basins were provided before the GRAIL mission (e.g., [3], [4], [5]). Later, un updated catalog of peak-ring basins and protobasins was then provided by [6]. However, Mars should be characterized by many more basins than observed (e.g., [7]), and previous databases suffered from difficulty of detection as a result of Martian sedimentary and erosive processes.

In our work we first develop a new approach to estimate the inner ring and rim crest sizes, based on the analysis of lunar gravity and crustal thickness data ([8], [9]), expanding upon the work of [2]. From this analysis, we also quantify how lower resolution gravity and crustal thickness datasets might bias the peak ring and main rim diameter estimates. Then, we present the first results obtained for Mars impact basins, working on the GMM-3 gravity [10] and crustal thickness data calculated after the Insight mission [11].

Methods:

In our approach, we first quantify the regional value of the Bouguer gravity anomaly and crustal thickness, which is defined as the average value obtained from azimuthally averaged profiles in the radius range 1.5 D to 2 D, where D is the crater diameter. The diameter of the Bouguer gravity high, as well as the diameter of the crustal thickness anomaly, were then estimated as the radius where the profiles first intersect the background regional values.

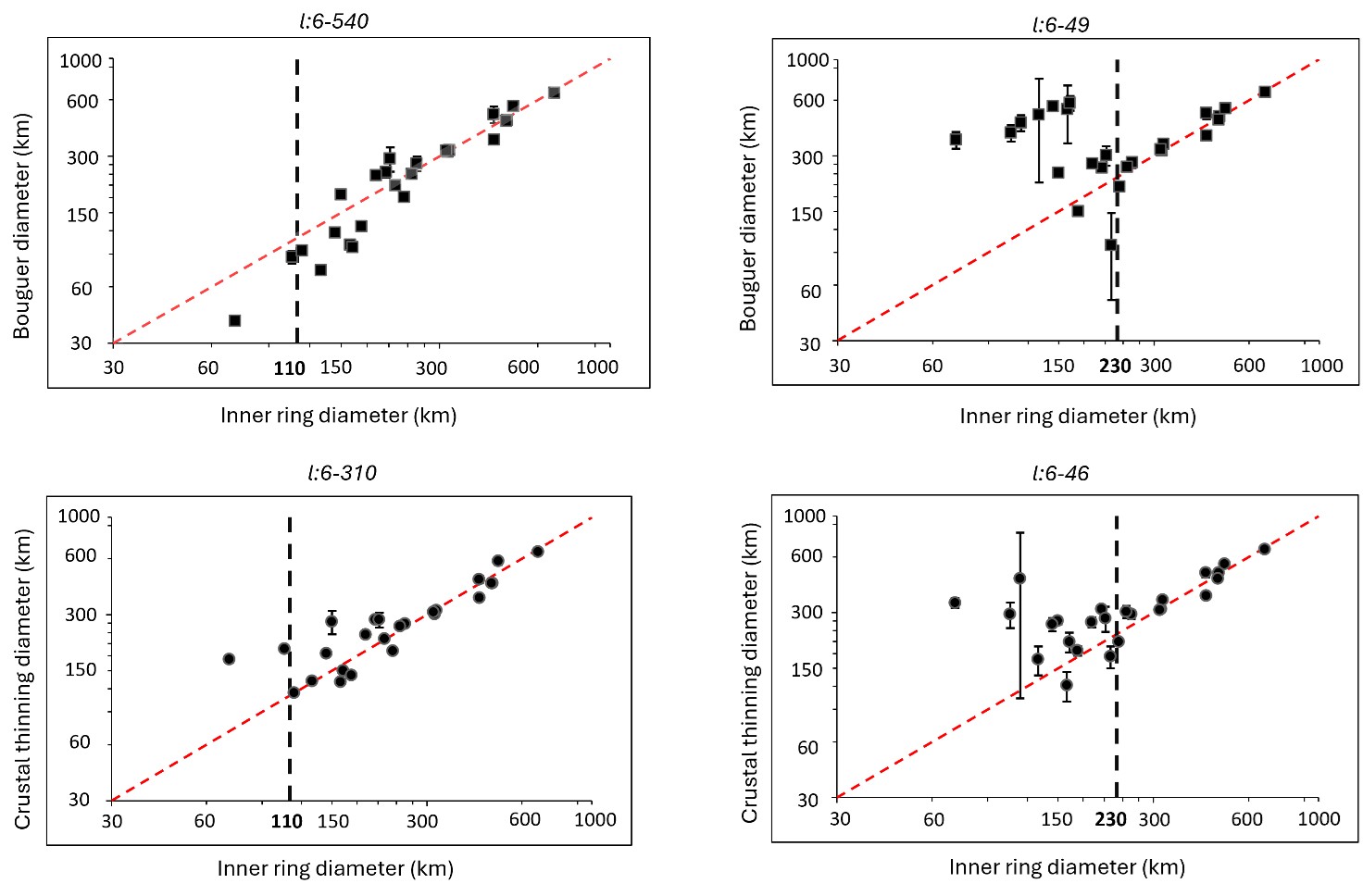

We tested this method using Bouguer gravity data for certain lunar peak-ring and multi-ring basins (see Table 1, e.g., [2]), by considering the spherical harmonic degree range from 6 to 540 (e.g., [2]). We then filtered the data using the spherical harmonic degree range 6-49 in order to simulate the lower resolution of the Mars gravity models. We then used the same approach using crustal thickness maps derived after GRAIL, both for the degree ranges 6-310 and 6-46, to simulate the loss of spatial resolution of Mars. Uncertainty estimates were obtained for the crustal thickness and the Bouguer anomaly diameter by considering the ±1σ values for the background values in the spatial range of 1.5D to 2D.

The same approach was used for eight Martian certain impact basins (see Table 2), based on the most updated catalogs ([5], [6]), including Antoniadi, Schiaparelli, Huygens, Cassini and four unnamed basins.

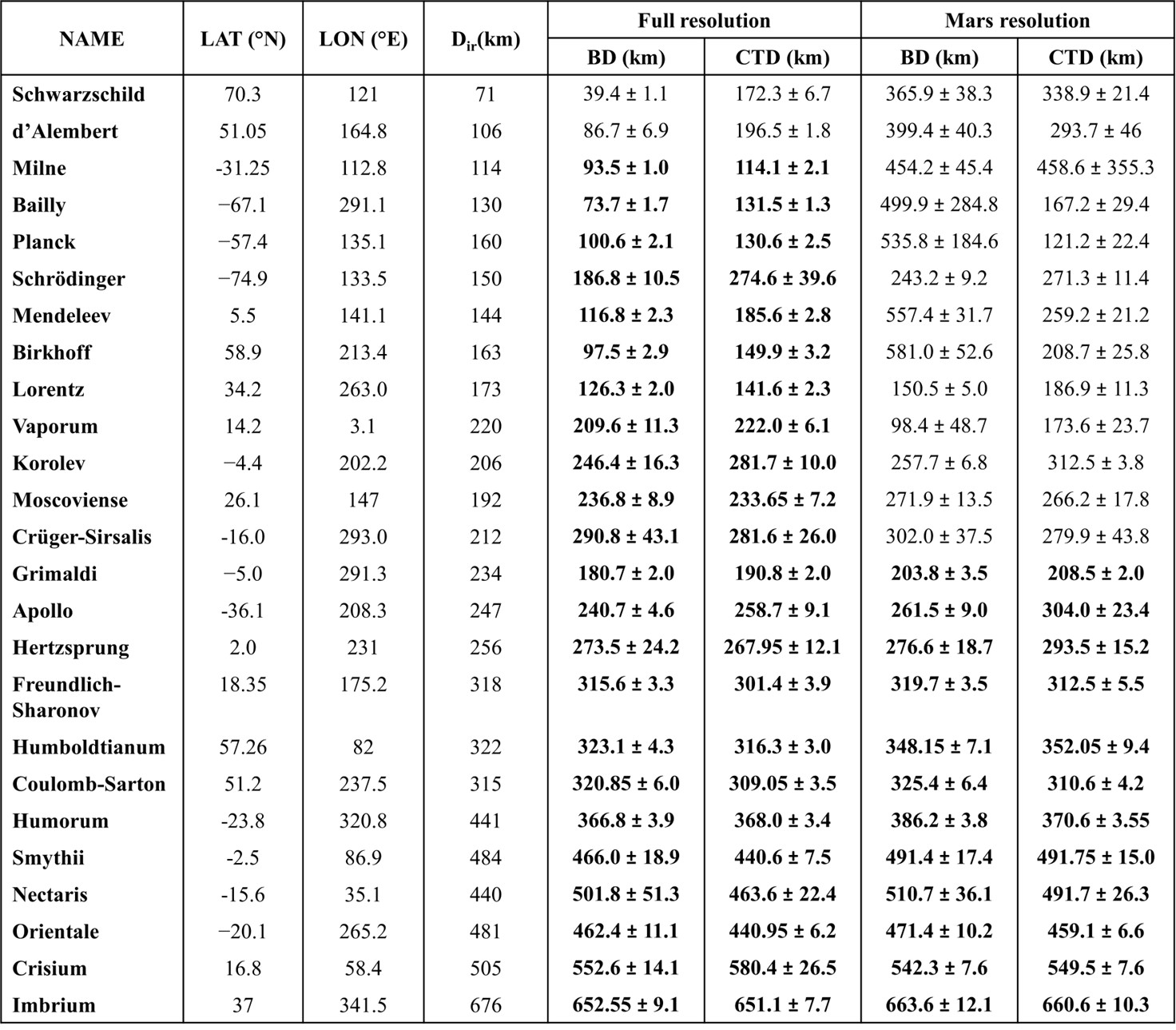

Table 1. Certain lunar impact basins (from database of [2]) considered in this work.

Dir: Inner ring diameter

BD: Bouguer diameter

CTD: Crustal thinning diameter

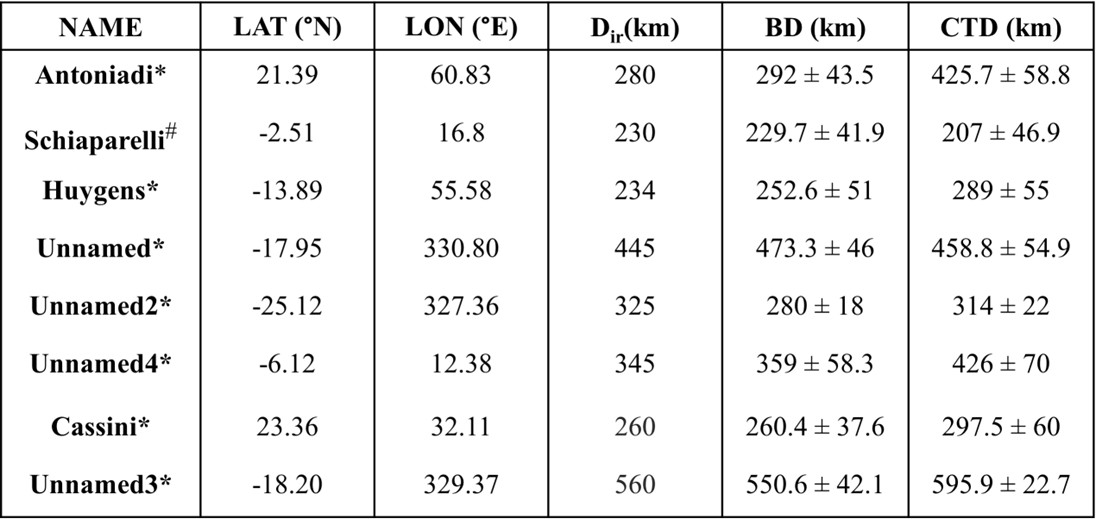

Table 2. Certain Martian impact basins considered in this work.

*[5] catalog; #[6] catalog

Conclusions and future work:

When considering the highest spatial resolution of the Bouguer gravity data and crustal thickness maps, our method properly detects peak-ring or inner ring sizes for lunar basins with main rim diameter greater than 250 km (i.e., for inner ring diameters greater than about 110 km). Nevertheless, when considering filtered versions of these datasets that correspond to the effective spatial resolution of the Mars gravity models, only basins with rim crest diameters greater than about 450 km can be detected with acceptable accuracy. Regardless, these results confirm a one-to-one relationship between the Bouguer anomaly diameter and the inner peak-ring diameter of lunar basins, as well as between crustal thinning size and peak-ring size (Fig. 1).

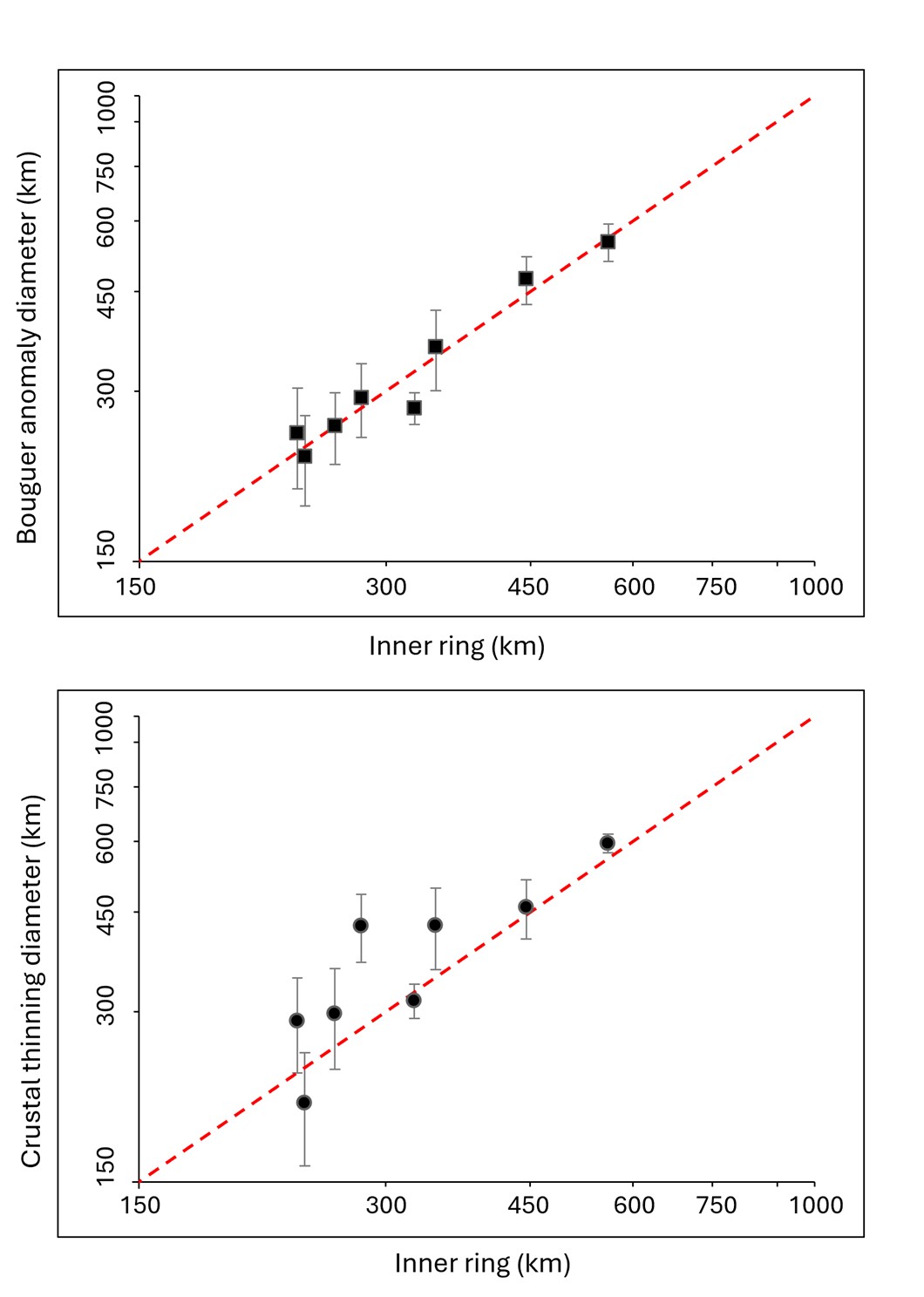

Results on Martian gravity data (Fig. 2) for eight selected certain peak-ring and multi-ring basins (e.g., [5],[6]) again confirm a 1:1 relationship between Bouguer anomaly diameter and the inner peak-ring diameter. Similar results were obtained when considering crustal thickness data.

We plan to apply this technique to first re-update the impact basins catalogs for the Moon and Mars, to obtain consistent database of basin sizes, and then Mercury, in view of the upcoming ESA-JAXA BepiColombo observations. We will also assess the use and advantage of gravity gradients and gravity tensor eigenvalues to determine Bouguer gravity size. Finally, these results will be useful to constrain the impact bombardment estimates of the early solar system.

Figure 1. Bouguer anomaly diameter (top) and crustal thinning diameter (bottom) versus peak-ring or inner-ring diameter (km) for certain lunar peak-ring and multi-ring basins (see Table 1, e.g., [2]). Red dashed lines indicate a 1:1 ratio.

Figure 2. Bouguer anomaly diameter (top) and crustal thinning diameter (bottom) versus peak-ring or inner-ring diameter (km) for certain Martian impact basins (see Table 2, e.g., [5], [6]). Red dashed lines indicate a 1:1 ratio.

References:

[1] Baker D. M. H., et al. (2011). Planet. Space Sci.

[2] Neumann G. A., et al. (2015). Sci. Adv.

[3] Frey H. V. (2008). Geophys. Res. Lett.

[4] Edgar L. A. & Frey H. V. (2008). Geophys. Res. Lett.

[5] Robbins S. J. & Hynek B. M. (2012). JGR: Planets.

[6] Baker D. M. (2016). In Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. XLVII.

[7] Robbins S. J. (2022). Planet. Sci. J.

[8] Goossens S. (2020). JGR: Planets.

[9] Wieczorek M. A., et al. (2013). Science.

[10] Genova A., et al. (2016). Icarus.

[11] Wieczorek M. A., et al. (2022). JGR: Planets.

Acknowledgements: We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Italian Space Agency (ASI) under ASI-INAF agreement 2024-18-HH.0.

How to cite: Buoninfante, S., Wieczorek, M. A., Galluzzi, V., Milano, M., Ferranti, L., Sepe, A., Fedi, M., and Palumbo, P.: A new geophysical approach to calculate the size of impact basins on the Moon and Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1563, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1563, 2025.