- 1Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands

- 2ESTEC, ESA, Noordwijk, The Netherlands

- 3Observatoire de Paris, Paris, France

[Introduction]

Between 2006 and 2016, Cassini collected high-precision Doppler measurements during ten of its Titan fly-bys. These data allowed the determination of Titan’s gravity field up to degree and order 5 [1, 2] and its tidal Love number k2 [2,3]. In this work we revisit the determination of this parameter, seeing as two existing determinations of k2 [2, 3] are statistically inconsistent, implying different characteristics of Titan’s interior structure, specifically the ocean density [3]. The conflicting results may stem from modelling differences, estimation settings or under-estimation of the error bars associated with the determined values. Using the open-source orbit and parameter estimation software Tudat [4] and a rigorous open-science approach, we aim to provide an independent, fully transparent re-analysis of the Titan flybys’ radio-science data, and thus help resolve the conflict from prior k2 estimates and its implications for the interior models. Here we present the results of the observational and dynamical models test, which demonstrate the suitability of the Tudat software to carry out this analysis.

[Modelling Results]

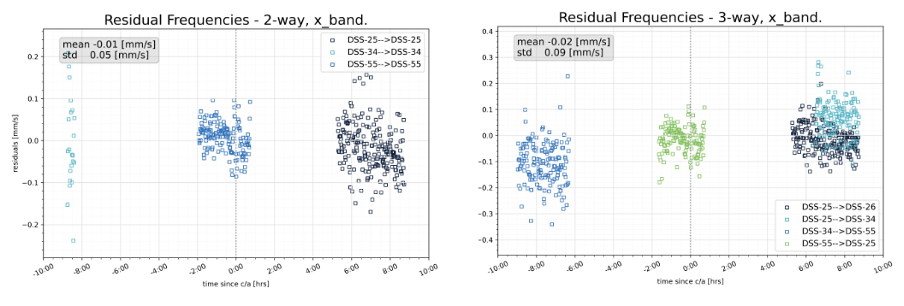

To isolate potential mis-modelling in the computation of the radiometric observables, we adopt a reference trajectory of the Cassini spacecraft from a spice-disseminated navigation solution, simulate the expected X- and Ka-band Doppler observables and compare them against the real observables. The inherent noise level of the 2-way Doppler observables is between 0.02 and 0.07 mm/s [3]. In the example of tracking pass T033, we demonstrate the computation of the observables to their noise level. When embedding the observables computation in an estimation, the small biases in the residual statistics are expected to be absorbed by ground station bias and clock synchronisation parameters. We conclude that the observables model is at the expected level.

Figure 1: Residuals from computed Doppler observables during Titan flyby T033, based on the Cassini reference trajectory.

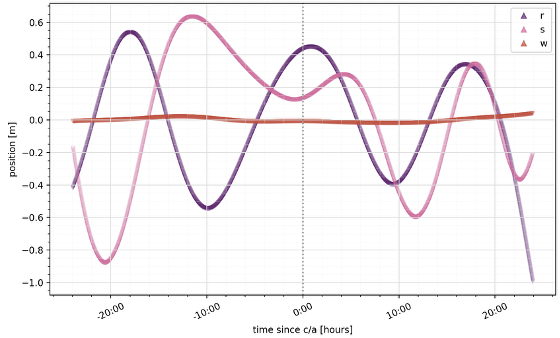

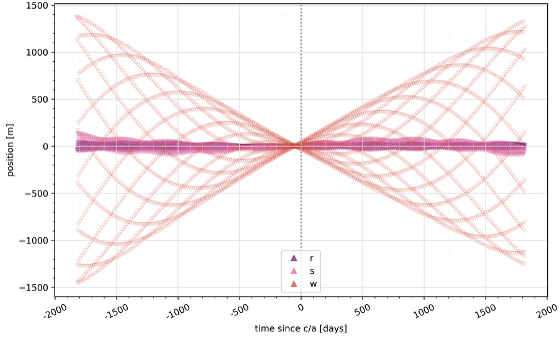

The detection of the acceleration exerted on the spacecraft due to the tidal response of Titan's gravity field demands a dynamical model of Titan that is sufficiently accurate over the timescale of the inversion. In the case of multi-arc estimation of the Titan ephemeris, as employed in prior analyses [2, 3], this timescale is in the order of two days. We aim to retrieve k2 alongside a single arc solution for the Titan ephemeris, which is beneficial for the accuracy and consistency of the determined value [2]. This requires the Titan dynamical model to be sufficiently accurate over multiple years [5], including subtle effects such as Saturn’s tidal dissipation at Titan’s forcing frequency and Saturn’s rotation pole motion. Eventually, a consistent single-arc ephemeris solution will also be critical to extract the tidal dissipation signature from Titan’s dynamics. Figure 2 demonstrates the accuracy of our model, which we derive from comparison with the numerical solution of Titan’s orbit from the Paris Observatory [6]. Titan position residuals over ± 24 hours (Fig. 2a) are contained within ± 1 m. The dynamical model is likely even more accurate, as the dominating in-plane signature is believed to originate from interpolation functions of the ephemeris kernel. Residuals over ± 5 years are contained within ± 100 m in-plane and grow up to 1500 m out-of-plane.

(a) Residuals over ± 24 h. Initial Titan state fitted to the reference ephemeris.

(b) Residuals over ± 5 years. Initial Titan state and Saturn's tidal quality factor fitted to the reference.

Figure 2: Titan position residuals in the orbit-defined RSW frame over the timescale of a single flyby pass (a) and all passes (b).

In addition to accurate dynamical models of the Titan dynamics, the trajectory of the Cassini spacecraft needs adequate modelling. This includes non-conservative forces like solar radiation pressure, thermal emissions from RTGs, and Titan’s atmosphere during low-altitude passes [2, 3]. Another challenge is reconstructing the motion of the low gain antenna phase center used during the high-latitude T110 flyby. These modelling efforts are still ongoing.

[Preliminary Conclusions and Outlook]

The models for Doppler observables were shown to be sufficiently mature to reproduce the Cassini observables to the accuracy of their inherent noise level. In several instances residual signatures were found. Their origin is still under investigation, but suspected to stem from the Cassini reference trajectory instead of the observable computation itself. We demonstrated a Titan dynamical model accuracy of < 1 m (Fig. 2a) on the timescale of individual passes, which is considered satisfactory for a multi-arc estimation. The current state of residuals over the 10 year interval (Fig. 2b) is promising with regards to enabling a global inversion with a single, consistent Titan ephemeris. Further work will investigate and mitigate the out-of-plane residual signature. The implementation of selected dynamical models for the Cassini spacecraft is ongoing.

Further tests of the Titan dynamical model over a timespan of 180 years show in-plane residuals within ± 2500 m and 50000 m out-of-plane. After mitigation of remaining out-of-plane deviations, we aim for an inversion of Titan’s dynamical model over periods much greater than the Cassini mission. Such an inversion could be constrained with additional astrometric observables from e.g. Voyager 1&2 and ground-based campaigns. We aim to recover parameters relating to the long-term evolution of Titan’s orbit (specifically the tidal quality factor of Saturn at Titan’s forcing frequency), with implications for the long-term history of the entire Saturnian system [6].

[1] Iess, L., et al. (2012). The tides of Titan. Science, 337(6093)

[2] Durante, D., et al. (2019). Titan's gravity field and interior structure after Cassini. Icarus, 326

[3] Goosens, S., et al. (2024). A low-density ocean inside Titan inferred from Cassini data. Nature Astronomy, 8(7)

[4] Dirkx, D., et al. (2022). The open-source astrodynamics Tudatpy software–overview for planetary mission design and science analysis. EPSC2022

[5] Fayolle, M., et al. (2022). Decoupled and coupled moons’ ephemerides estimation strategies application to the JUICE mission. Planetary and Space Science, 219

[6] Lainey, V., et al. (2020). Resonance locking in giant planets indicated by the rapid orbital expansion of Titan. Nature Astronomy, 4(11)

How to cite: Hener, J., Dirkx, D., Fayolle, S., Gisolfi, L., Filice, V., Lainey, V., and Visser, P.: Re-visiting determination of Saturn-Titan tidal interaction parameters using the open-source Tudat software., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1567, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1567, 2025.