- 1Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation Science, Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

- 2Macau University of Science and Technology, Avenida Wai Long, Taipa, Macau

Introduction:

Ceres, the largest body in the asteroid belt, became the first dwarf planet orbited by a spacecraft when NASA’s Dawn mission arrived in 2015. Located at 2.767 AU from the Sun and rotating every ~9.07 hours [1], recent gravity data suggest Ceres retains a fossil equatorial bulge, hinting at a faster past rotation, possibly despun by 6.5%, potentially resulting from the loss of a satellite or a major impact event [2,3,4].

Methodology:

We build on internal structure models from [5], exploring various formation and accretion scenarios (Table 1) to examine how Ceres’ interior evolution influences its angular velocity and energy state. Our primary focus is a scenario where Ceres accreted over 10 Ma in the Kuiper Belt with a 3:1 dust-to-ice ratio, then migrated to the asteroid belt ~600 Ma after CAI formation, completing the migration within 1 Ma. We analyze how this formation pathway affects the evolution of its MOI, angular velocity, kinetic energy, and potential energy, including an analytical approximation of the latter. The resulting normalized MOI is compared with the spacecraft-derived range of 0.345–0.375 [4] to assess the plausibility of this scenario.

Results:

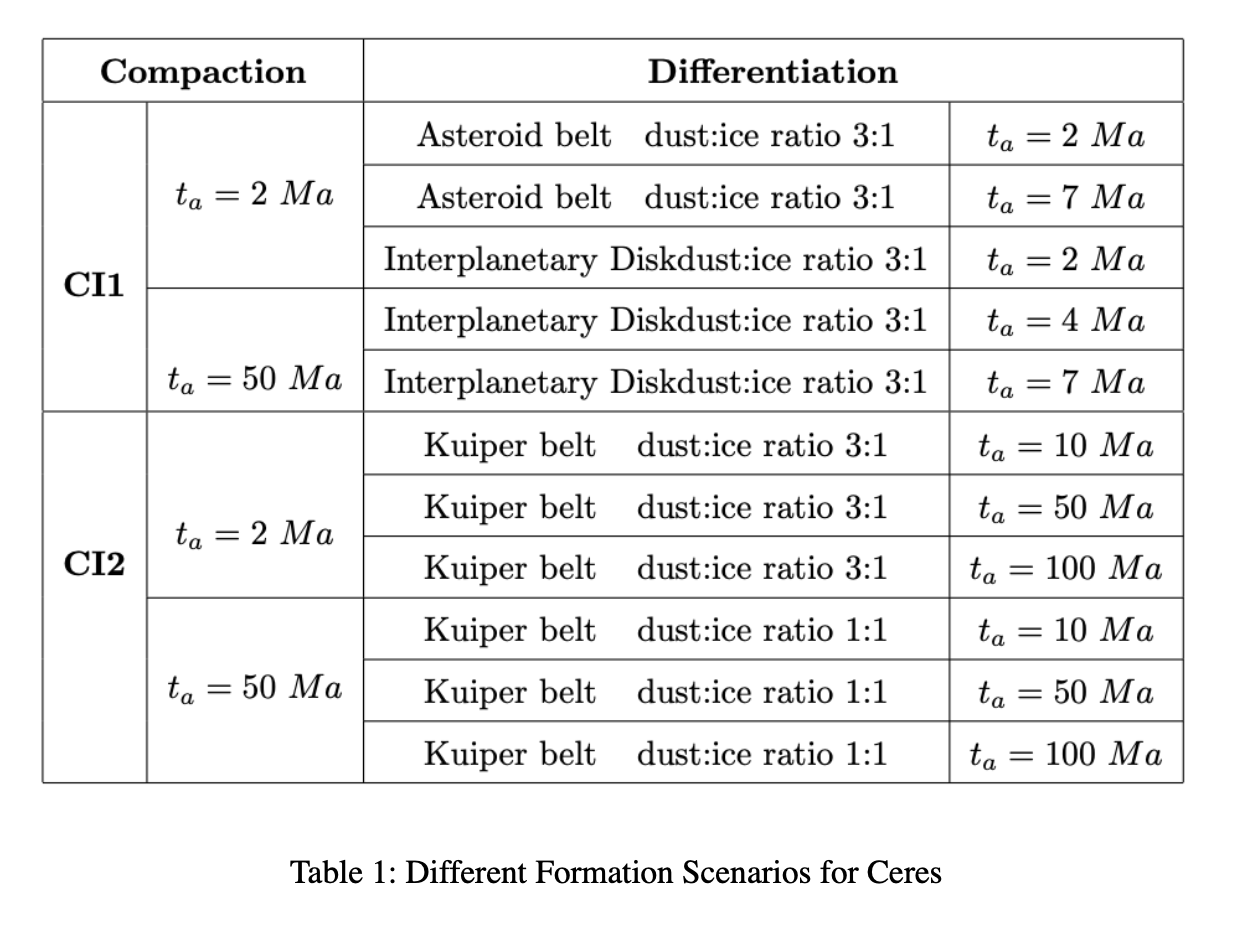

MOI

Figure 1 illustrates how Ceres’s thermal and internal evolution influenced its MOI. In the 3:1 rock-to-ice composition scenario, early radiogenic heating was dominated by the rock component, primarily driven by short-lived isotopes. However, due to the prolonged accretion timescale of 10 Ma, most of the short-lived isotopes had decayed by the end of accretion. Consequently, internal heating was sustained mainly by long-lived isotopes. Formation in the cold Kuiper Belt further suppressed internal temperatures, limiting early differentiation. As a result, Ceres likely developed only a partially dehydrated silicate core, with substantial amounts of ice and porosity preserved in its interior. Despite this subdued internal evolution, the degree of differentiation and compaction was sufficient to reduce the MOI to ~0.369, which falls well within the observed range of 0.345–0.375. These results support are in line with the Kuiper Belt origin for Ceres, consistent with current geophysical constraints.

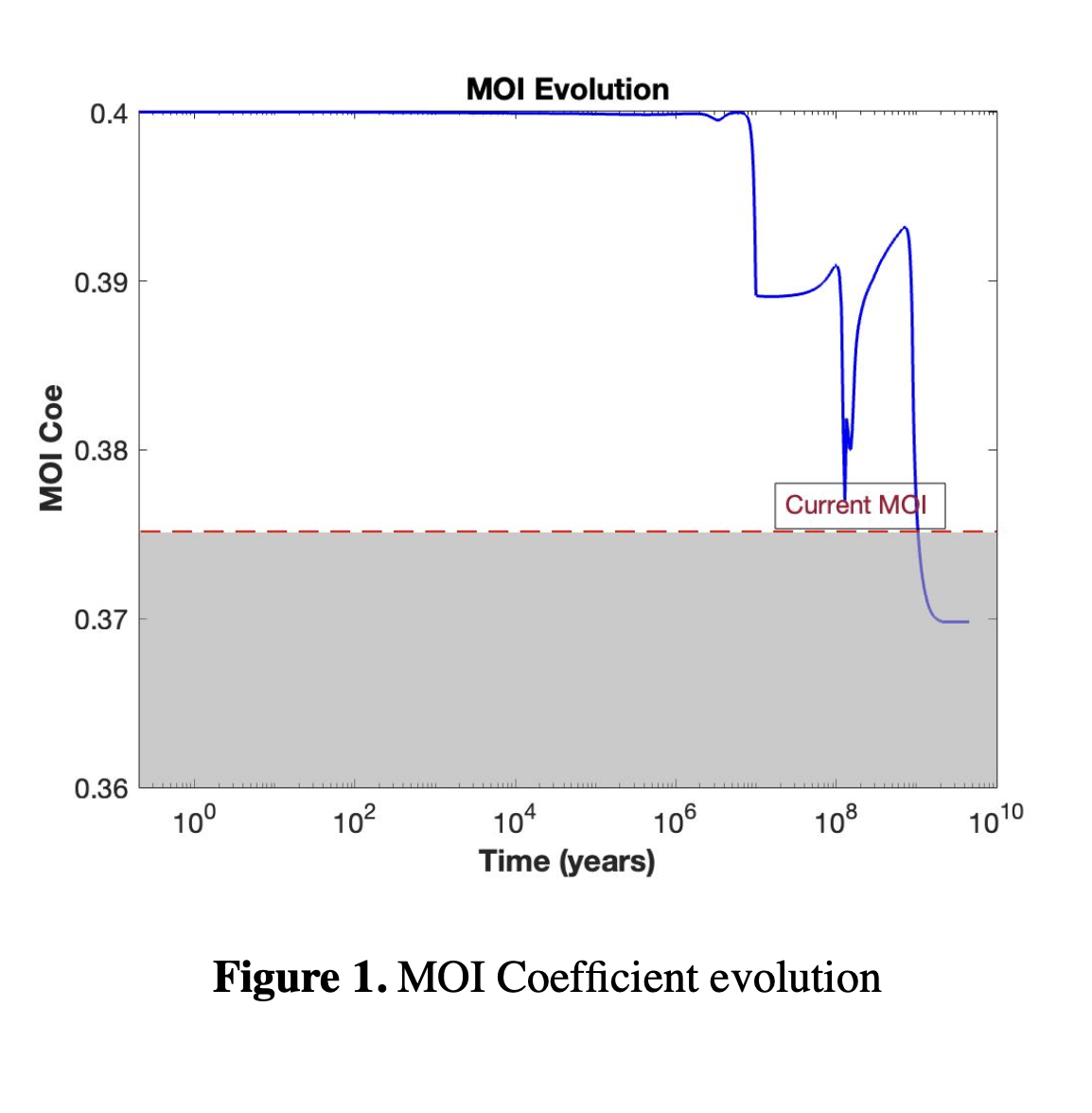

Angular Velocity

Figure 2 illustrates that the most significant angular velocity increase occurs in the Kuiper Belt formation scenario. As Ceres migrates from ~40–50 AU to ~2.7 AU, possibly associated with theLate Heavy Bombardment or the Nice Model, rising environmental temperatures cause internal restructuring, including ice sublimation and porosity collapse. Two spikes in angular velocity are evident in Figure 2: the first likely due to a differentiation in the cold Kuiper Belt (~50 K), drivenprimarily by radioactive isotopes, and the second resulting from restructuring in the warmer asteroid belt (~170 K), which caused mass redistribution, lowering the MOI and increasing angular velocity by ~45% to conserve angular momentum—significantly higher than the ~6% despin previously proposed by [4], who assumed a static internal structure.

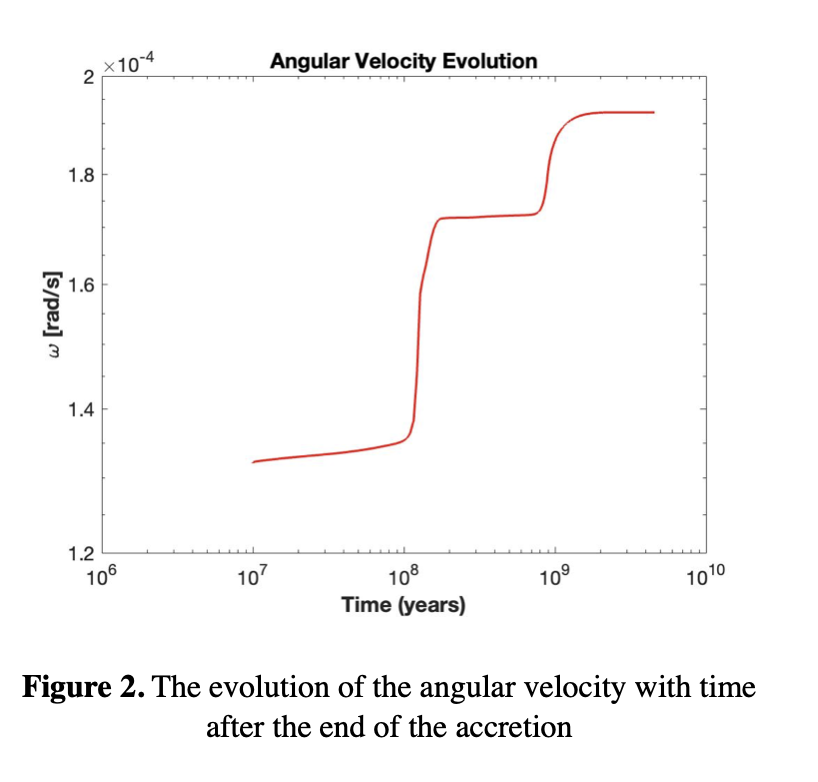

Kinetic Energy

Figure 3 shows corresponding increases in kinetic energy during phases of angular velocity change. The sharp rises in KE coincide with internal differentiation events, highlighting the linkbetween structural evolution and rotational dynamics. These findings emphasize that rising temperatures during migration triggered the mechanical collapse of porous ice-rock mixtures and differentiation, releasing energy as Ceres adjusted to a new equilibrium state.

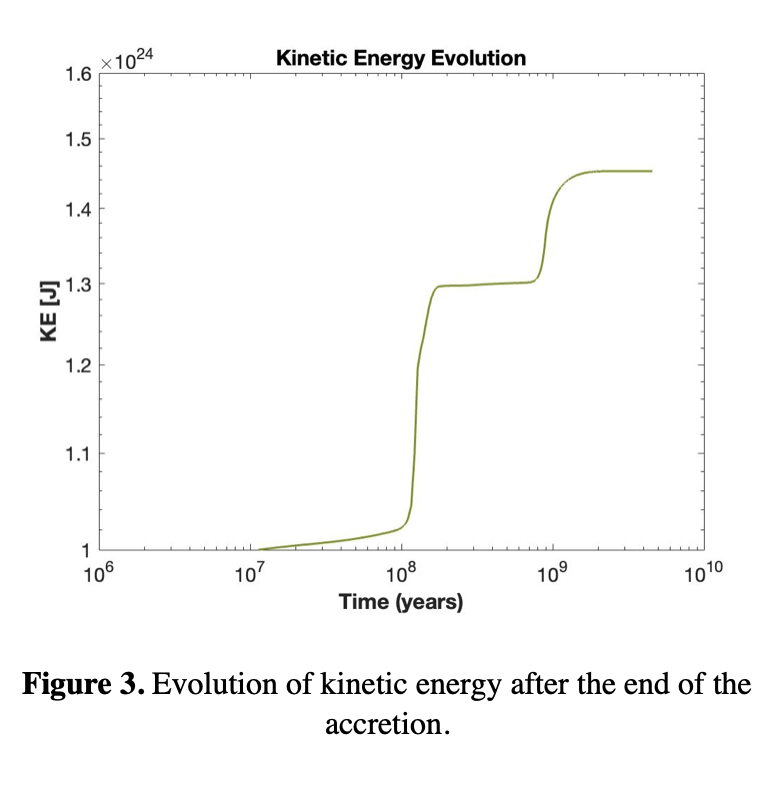

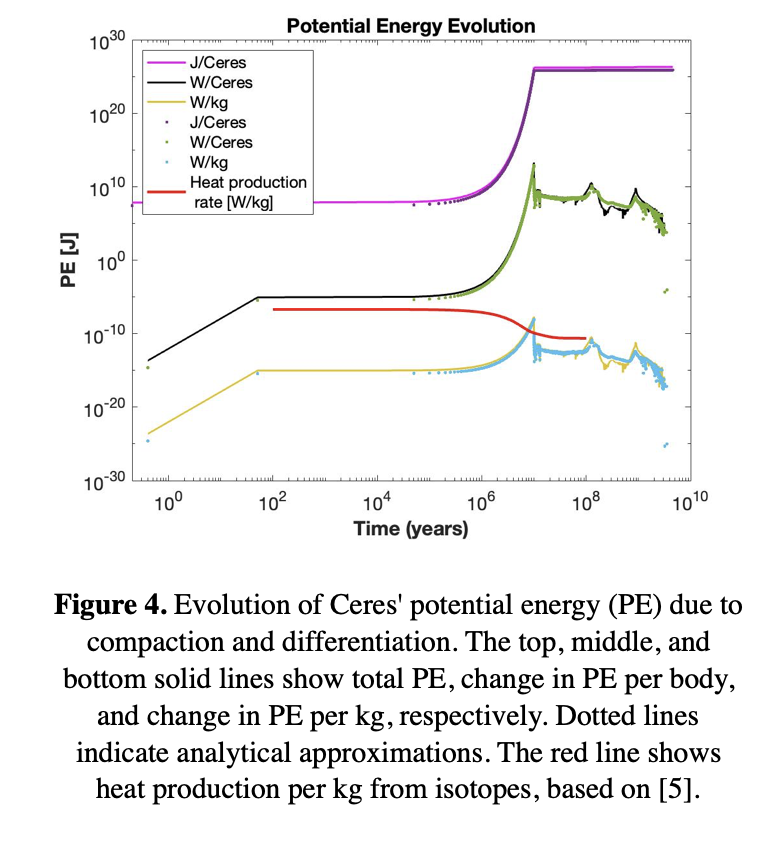

Gravitational Potential Energy

As shown in Figure 4, Ceres’ gravitational potential energy increases during accretion as mass accumulates and self-gravity strengthens. After accretion, fluctuations in potential energy reflect mass redistribution resulting from porosity reduction and internal differentiation. Earlyheating was significantly driven by the decay of short-lived nuclides, though this effect diminished rapidly, with long-lived isotopes sustaining a slower thermal evolution thereafter. Distinct steps in the potential energy curve correspond to major structural changes, particularly during the transition from Kuiper Belt to asteroid belt conditions.

Conclusion:

This study investigates how internal structure, thermal evolution, and migration history influence the rotational dynamics and energy budget of Ceres. Focusing on a Kuiper Belt formation scenario followed by inward migration, we find that the computed MOI values are consistent withcurrent gravity and shape data [4], supporting the plausibility of this origin. Notably, we show that Ceres’ angular velocity could have increased by ~45% due to internal restructuring driven by thermal changes and subsequent evolution, significantly higher than previous estimates [4].These findings highlight internal evolution and environmental transitions as key drivers of planetary spin states and energy distributions.

[1] M.A. Chamberlain et al., Icarus 188, 451 (2007).

[2] X. Mao and W.B. McKinnon, LPSC 47, 1637 (2016).

[3] X. Mao and W.B. McKinnon, LPSC 48, 2744 (2017).

[4] X. Mao and W.B. McKinnon, Icarus 299, 430 (2018).

[5] W. Neumann et al., A&A 633, A117 (2020).

How to cite: Darivasi, D., Oberst, J., and Wladimir, N.: Internal Structure and Dynamical Evolution of Ceres, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1591, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1591, 2025.