Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

SB6

The session will gather researchers of different communities for a better understanding of the evolution and properties of small bodies, ranging from planetesimals or cometesimals to icy moons, and including meteorite parent bodies. It will address recent progresses made on physical and chemical properties of these objects, their interrelations and their evolutionary paths by observational, experimental, and theoretical approaches.

We welcome contributions on the studies of the processes on and the evolution of specific parent bodies of meteorites, investigations across the continuum of small bodies, including comets and icy moons, ranging from local and short-term to global and long-term processes, studies of the surface dynamics on small bodies, studies of exogenous and endogenous driving forces of the processes involved, as well as statistical and numerical impact models for small bodies observed closely within recent space missions (e.g., AIDA, Hayabusa2, Lucy, New Horizons, OSIRIS-REx).

Session assets

Recently, data from the OSIRIS-REx mission revealed evidence of layering, where fine-grained material on Bennu could be located at depth, not far below the asteroid’s surface (Bierhaus et al., 2023). If present and distributed globally, this fine-grained material could be more cohesive than the coarser and typically unconsolidated surface material, and would provide a relative stronger substrate at depth. Several lines of evidence indicate that Bennu’s interior should possess such strength, including but not limited to its non-circular equatorial ridge (Barnouin et al., 2019), the presence of surface lineaments (Barnouin et al., 2019; Jawin et al., 2022), and the widespread evidence of surface mass movement (Barnouin et al., 2022; Jawin et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2023; Walsh et al., 2019). Understanding properties including cohesion, particle size distribution, and structure is key to interpreting an asteroid’s geologic history. One manifestation of our uncertainty in asteroid surface properties is a mismatch in the crater-derived surface ages of NEAs such as Bennu and Ryugu, which are orders of magnitude younger than the proposed age of the breakup of their parent bodies.

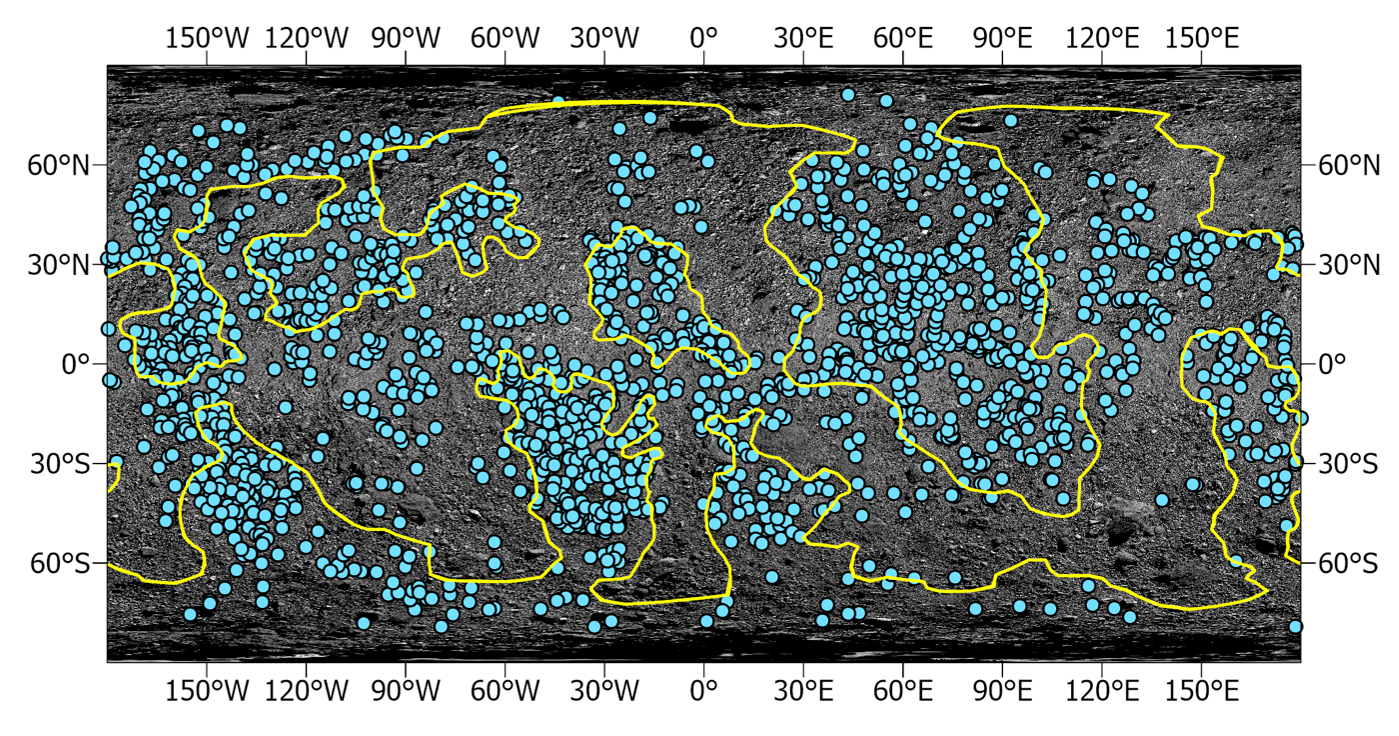

Figure 1. Global image mosaic showing smooth regions larger than ~1 m (circles) compared to global geologic units (yellow outline). Smooth regions are concentrated in the Smooth Unit (regions including the north and south poles), although smooth exposures are also present in the Rugged Unit (covering most of the equatorial zone).

Here, we begin to explore in detail the spatial distribution and physical attributes of the exposed subsurface, fine-grained layer. Our approach is to systematically identify smooth areas across the asteroid, where the more cohesive fines might exist, with the ultimate objective to test the hypothesis of the presence of this fine-grained subsurface layer, in part by establishing the stratigraphic height of any exposed fine-grained material.

Identifying smooth areas:

We visually identify smooth regions in a global image mosaic generated from the Detailed Survey phase of the mission with a pixel scale of ~5 cm (Bennett et al., 2021) (Fig. 1). This initial mapping identified relatively smooth-textured areas regardless of objective roughness or geologic setting (i.e., not restricted to impact craters). Additional analyses will survey the polar regions, define spatial extents of smooth exposures, merge overlapping regions, remove any regions smaller than our minimum diameter of 5 m, and will identify regions for subsequent SFD analyses.

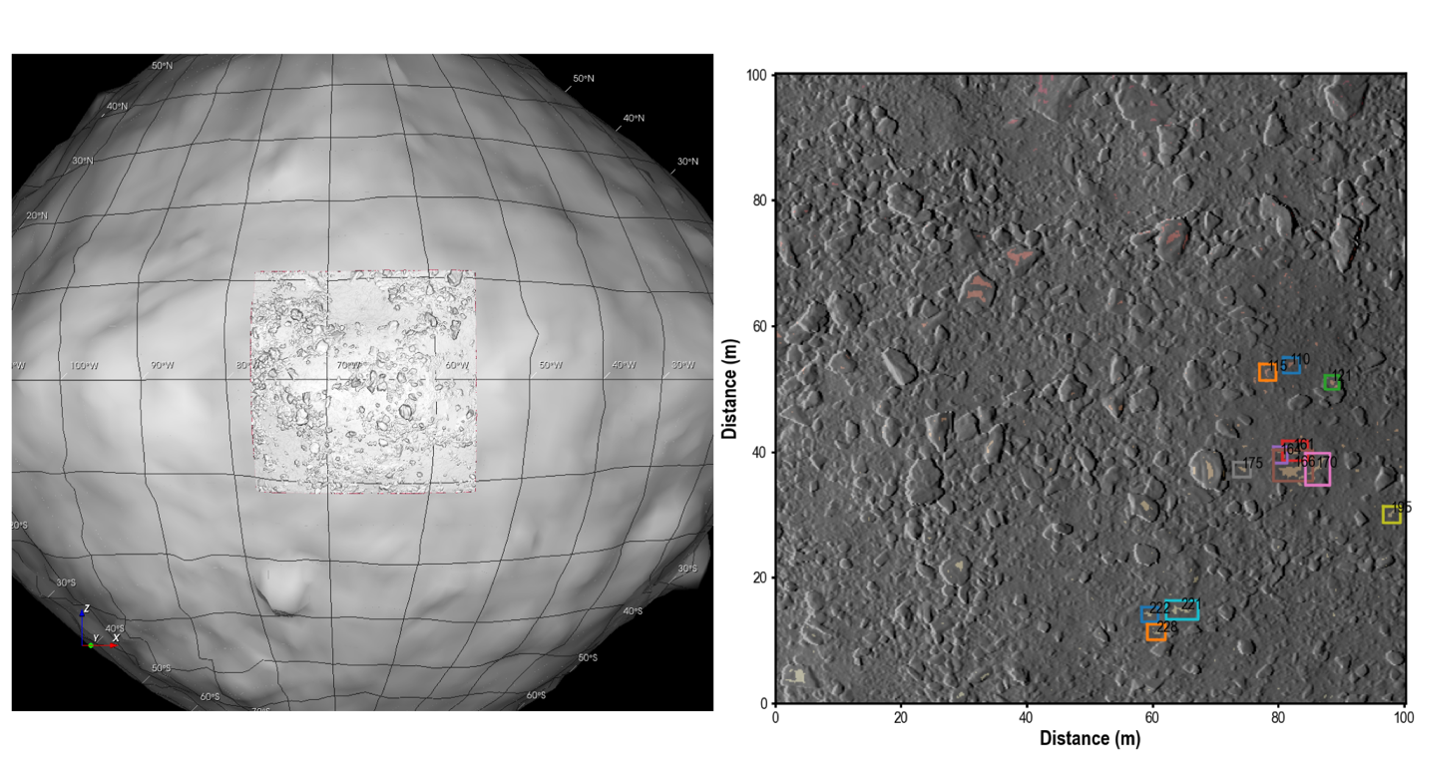

We also identify and map smooth regions on a global set of 20 cm digital terrain models (DTM) that were generated using OLA data collected during the prime mission. As available in the Small Body Mapping Tool, these 20 cm DTMs include the variation of surface tilts across the surface of Bennu, within a 1-m diameter region, centered on each one of the DTM’s facet. The tilt variation is determined by taking the root mean square of variation of each facets tilt relative to the mean tilt of 1 m region. Surfaces that have a greater tilt variation are typically rougher than regions that do not. To find the smoothest areas, we filter this tilt variation < 4 deg. We also filter out boulder tops, many of which are very smooth (Fig. 2). The remaining regions are tracked by location, elevation, radius, and so on.

Fig. 2 Twenty-cm DTM located on Bennu (left), with smooth regions identified (right) as colored patches. Boxed regions were ultimately considered in this analysis. Other patches are usually boulder tops, which are often smooth.

Numerical assessments

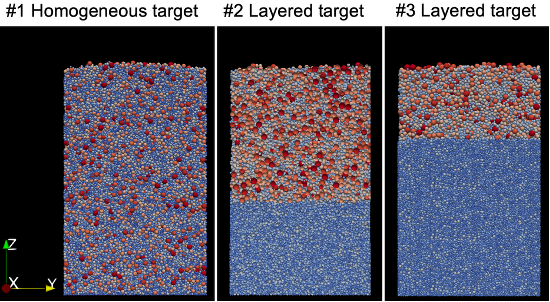

To complement our systematic mapping efforts, we have also undertaken a suite of numerical investigations that make use of the Soft-Sphere Discrete Element Model code PKDGRAV. We hypothesize that a near-surface layer of fine-grained material, owing to its stronger cohesion, could facilitate mobilization of the overlying coarse regolith, thereby enhancing surface mass movement compared to an unlayered target. If this hypothesis is correct, then the geotechnical properties of the granular material should depend on: (1) particle SFD, (2) particle size range, and (3) confining pressure. To systematically study how these factors interact and influence the mechanical behavior of Bennu’s surface and near-surface regolith, we perform triaxial compression tests using PKDGRAV. We further conduct landslide simulations using granular beds with various surface and subsurface structures (Fig. 3) to assess their surface mobility. These efforts consider Bennu gravitational conditions.

Fig. 3 Examples of subsurface structures used in the numerical simulations for testing surface mobility. Particles are color-coded by their radii.

Current status of findings:

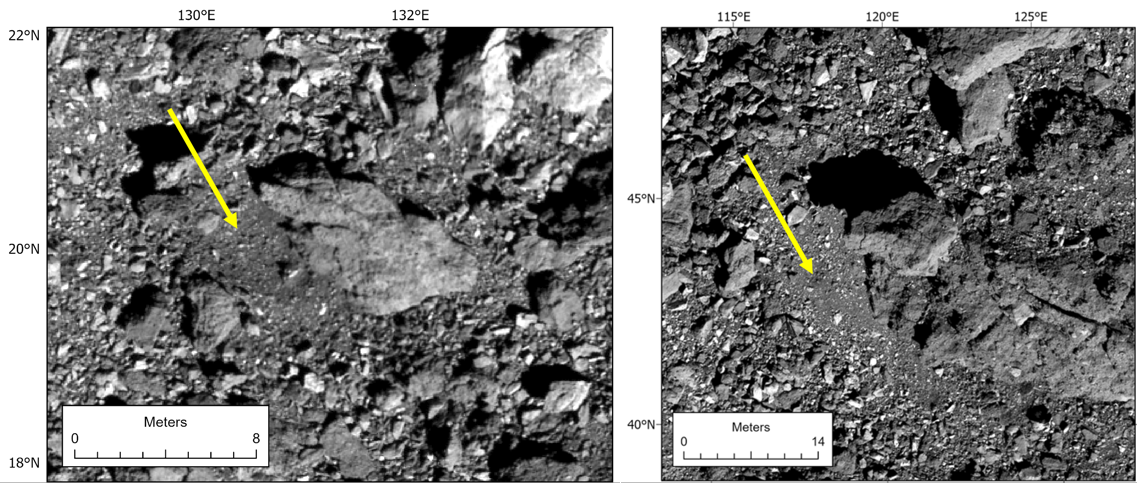

Our initial spatial trends suggest that smooth exposures are more prevalent in the Smooth Geologic unit (compared to the Rugged unit), although smooth regions are also found in the Rugged unit that may be associated with the movement of large boulders via impacts and/or mass movement (Fig. 1). We also find that smooth areas are often, but not always, associated with small fresh (red) craters. Many of the smoothest regions also exist between boulders, including the largest boulders (>20-30 m diameter) which have previously been associated with recent mass movement activity (Daly et al., 2020; Jawin et al., 2020). Some of the most interesting smooth regions are found down-slope of a larger boulder, where coarse surface material appears to have slid away, exposing the fines (Fig. 4?). Our ongoing numerical investigation will provide a better understanding for what near-surface conditions were needed to achieve these observations.

Figure 4. Examples of smooth regions downslope of large boulders on Bennu.

References:

Barnouin, O.S., et al., 2019. Nature Geoscience 12, 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0330-x

Barnouin, O.S., et al., 2022. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 127, e2021JE006927. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JE006927

Bennett, C.A., et al., 2021. Icarus 357, 113690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.113690.

Bierhaus, E.B., et al., 2023. Icarus 115736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115736

Jawin, E.R., et al., 2022. Icarus 381, 114992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2022.114992

Jawin, E.R., et al., 2020. J Geophys Res-Planet 125. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JE006475

Tang, Y., et al., 2023. Icarus 115463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115463

Walsh, K.J., et al., 2019. Nature Geoscience 12, 242–246. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0326-6

How to cite: Barnouin, O., Jawin, E., and Yun, Z.: Characterizing a near-surface, fine-grained layer on Bennu. , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-346, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-346, 2025.

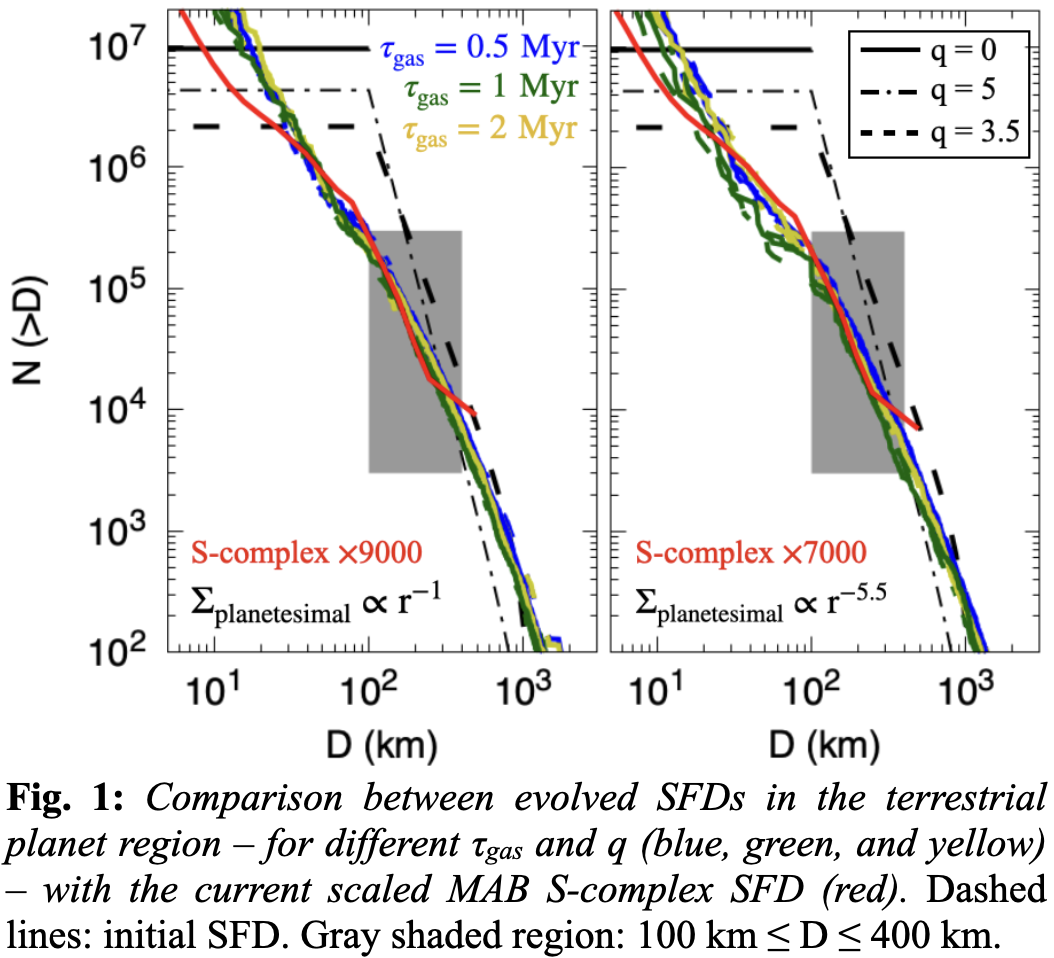

We recently proposed that the Massalia asteroid family is the source of the most common meteorites found on Earth: the ordinary L chondrites (Marsset, Vernazza, Brož et al. 2024, Nature). This hypothesis is supported by several lines of evidence:

(1) spectral similarities between Massalia family members and L chondrites;

(2) the family’s steep size-frequency distribution, extending down to the detection limit of current all-sky surveys, indicating a large population of small fragments;

(3) the orbital clustering of L-chondrite-like Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) near the family and the 3:1 mean-motion resonance with Jupiter;

(4) the presence of a zodiacal dust band intersecting the family, suggesting ongoing dust production that feeds the inner Solar System;

(5) the dynamical and collisional ages of the family, which we found to be consistent with the argon isotope ages measured in L chondrites;

and (6) the reconstructed pre-atmospheric orbits of L chondrites, pointing to a low-inclination source in the inner asteroid belt.

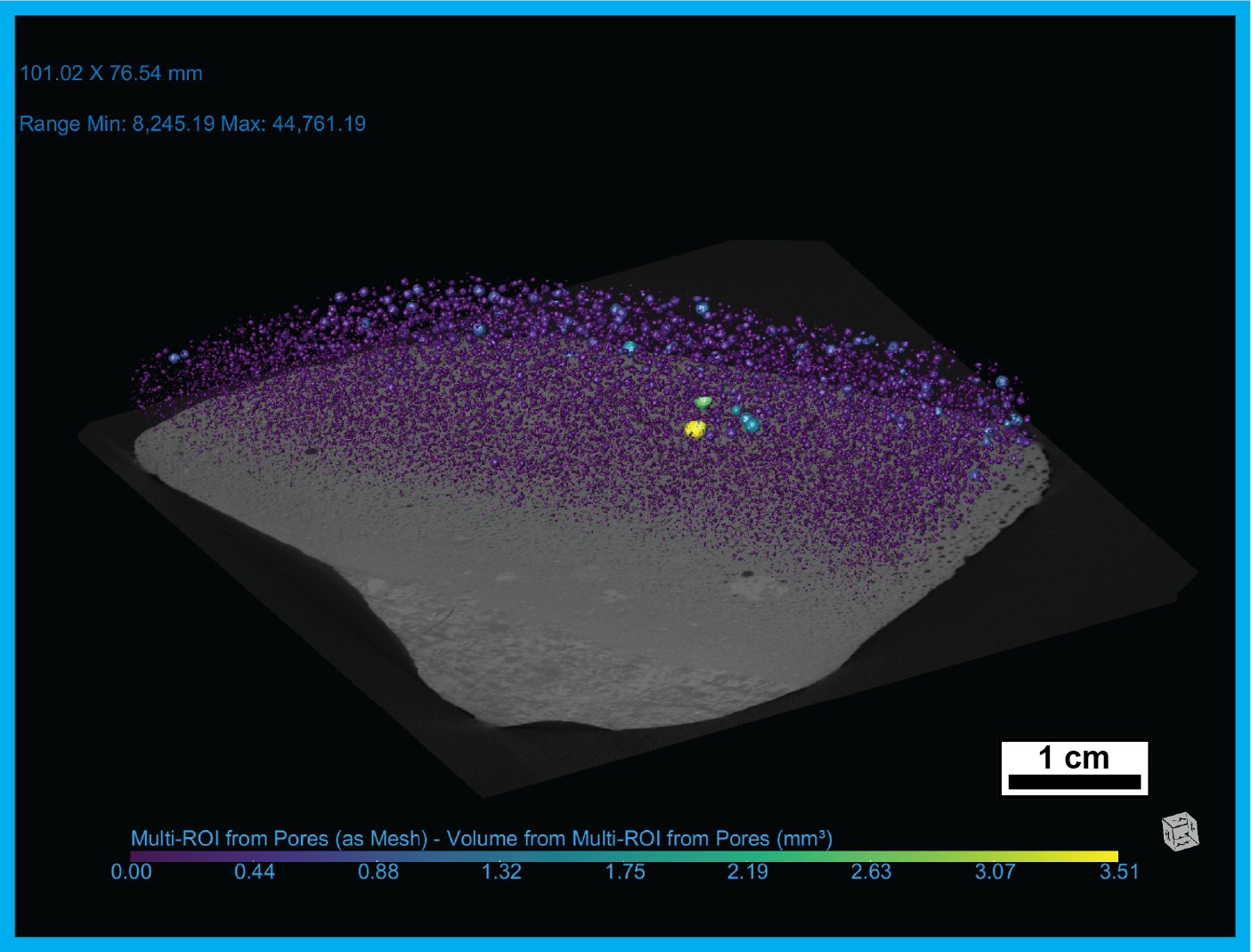

In our initial study, we made several testable predictions for future large-scale surveys (e.g., LSST) and targeted observations to further validate our finding. One such prediction was the existence of a large impact crater on (20) Massalia itself. Here, we present high-resolution adaptive optics (AO) images of Massalia obtained with VLT/SPHERE to test this prediction. By combining these multi-epoch AO observations covering a full rotation with optical light curves , we determined the asteroid’s spin orientation and derived a detailed shape model. Additionally, we analyzed an extensive set of thermal measurements to estimate (20) Massalia’s thermal inertia and surface roughness. We will discuss these results in the context of the proposed link between the Massalia family and L chondrites.

How to cite: Marsset, M., Hanuš, J., Mueller, T., Vernazza, P., Brož, M., and Thomas, C.: Searching for the Cradle of L Chondrites on (20) Massalia's Surface, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-60, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-60, 2025.

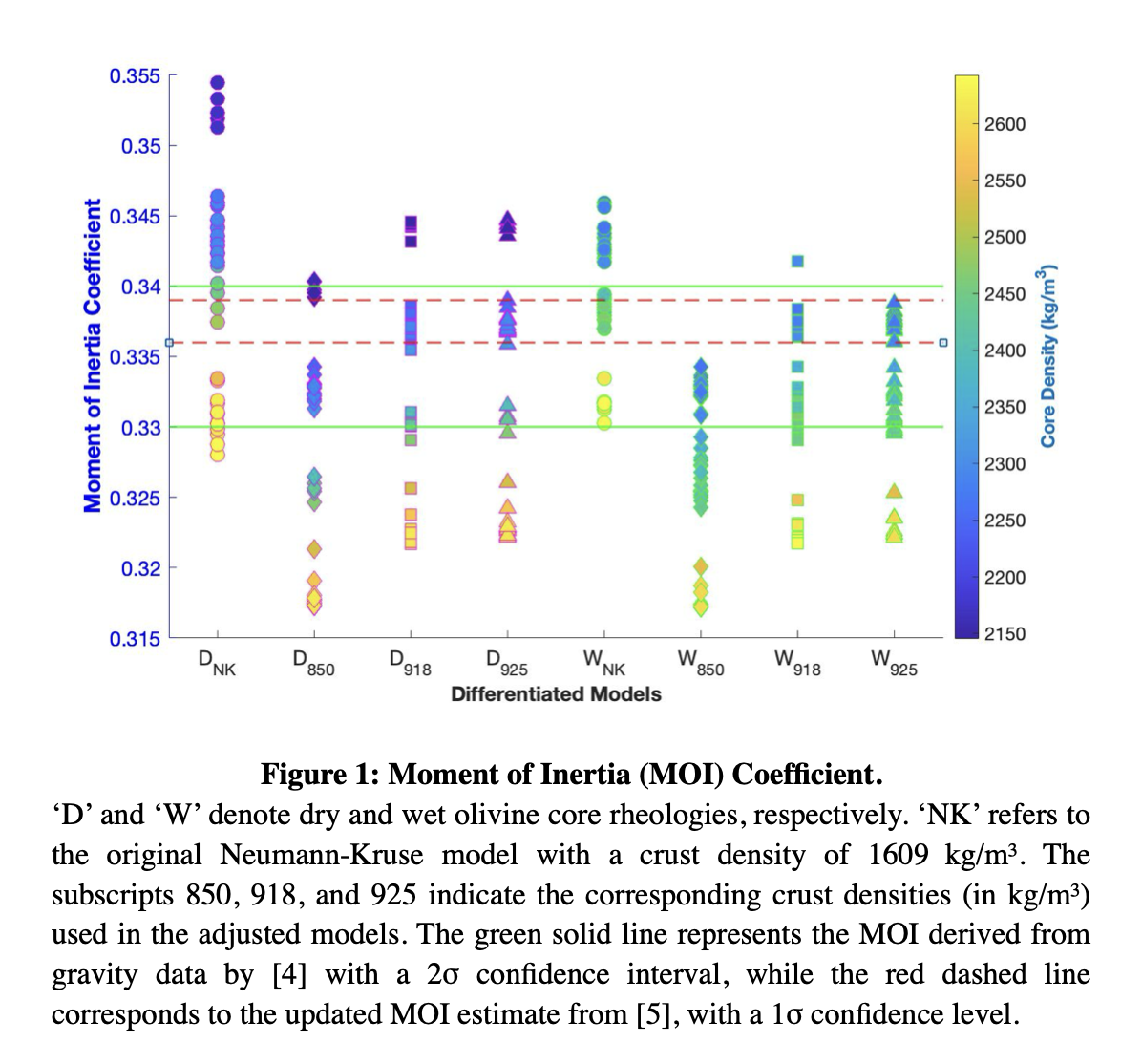

In the classical theory of planetesimal differentiation, a body would form an iron-rich core, an olivine-dominated mantle, and a pyroxene-rich basaltic crust [1]. The detection of differentiated bodies in the current asteroid main belt will allow us to get insights and study the very initial phases of planetesimal accretion. So far, the only striking proof of a differentiated planetesimal is asteroid (4) Vesta and its family that resulted from the impact formation of two large basins Rheasilvia and Veneneia [2]. Asteroid (22) Kalliope is the densest known asteroid with ⍴=4.4±0.46 g.cm-3 [3] indicating a metal-rich composition. The low radar albedo (0.18±0.05 [4]), however, points towards a lower metal content on the surface but the presence of very high density indicates a differentiated metal-rich interior. (22) Kalliope has recently been shown to be the parent body of an asteroid family in the outer main belt consisting of 302 members [5]. Therefore, studying the physical properties of the Kalliope family members we can get insights into the internal structure of the original planetesimal. In this work we studied the physical properties of the Kalliope family. Thirty seven Kalliope family members have visible reflectance spectra from Gaia DR3 and 22 of which were observed at NASA IRTF obtaining their near-infrared spectra. Following the methodology of our previous work on the Athor asteroid family [6], Gaia and IRTF spectra were combined with the available visible SDSS data. The final combined spectra were classified in the Bus-DeMeo taxonomy [7]. Using the reflectance spectra of Kalliope family members as well as their geometric visible albedos we matched them with meteorites that are included in the RELAB and PSF meteorite lab spectra databases. We discovered that the Kalliope family is the first family that consists of metallic fragments, confirming the differentiated nature of the original planetesimal [8].

References: [1] Elkins-Tanton, L. and Weiss, B. (2017), Planetesimals, Cambridge University Press. [2] Marchi S. et al. (2021) Science 336, Issue 6082, 690. [3] Ferraris M. et al. (2022) A&A, 622, A71. [4] Shepard M. K., et al. (2015) Icarus, 245, 38. [5] Brož M. et al. (2022) A&A, 664, A69. [6] Avdellidou C. et al. (2022) A&A, 665, L9. [7] DeMeo F. E. et al. (2009) Icarus, 202, 160. [8] Avdellidou C. et al. (2025) MNRAS.

How to cite: Avdellidou, C., Bhat, U., Bujdoso, K., Delbo, M., Marsset, M., and Vernazza, P.: Kalliope sings rock and metal., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1549, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1549, 2025.

Near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) offer unique laboratories for probing the internal structure and cohesion of small bodies. Although most asteroids spin more slowly than the so‑called “cohesionless spin barrier” (a ∼2.2 h rotation period above which a rubble pile would disrupt), a growing handful of NEAs exhibit much shorter periods, calling into question our understanding of their mechanical strength and aggregate structure.

Measuring sub‑barrier spin rates is challenging: wide‑field surveys rarely provide the continuous, high‑cadence photometry needed to resolve rapid light‑curve variations over several hours. Dedicated follow‑up with robotic telescopes is therefore essential to capture the dense temporal sampling required to detect and characterize fast rotators.

Here we report on an ongoing survey targeting NEAs with absolute magnitude H > 22.5, carried out with four new robotic instruments at Teide Observatory, Tenerife: two 0.8 m telescopes (TTT‑1/2), a 1 m wide‑field telescope (TST; 4.1 deg² FOV), and a 2 m telescope (TTT‑3). All are equipped with high‑sensitivity sCMOS cameras optimized for rapid, low‑noise photometry. For the 2 m telescope, individual observing blocks are constrained to under 40 minutes, whereas on the 0.8 m telescopes we employ two‑hour blocks to secure adequate temporal coverage of fast rotators.

To date we have observed over seventy NEAs within days of discovery, identifying more than 55 previously unreported fast rotators. Preliminary statistics indicate that 91 % of our sample with H > 24 rotate faster than the spin barrier, and every one of fourteen targets with H > 26 exhibits sub‑barrier spin periods—several completing a full rotation in under a minute. We also report at least five new non‑principal‑axis (tumbling) rotators, a substantial increase over the thirteen known to date. These results underscore both the prevalence of rapid spin states among the smallest NEAs and the power of dedicated, high‑cadence follow‑up in expanding our knowledge of their physical properties.

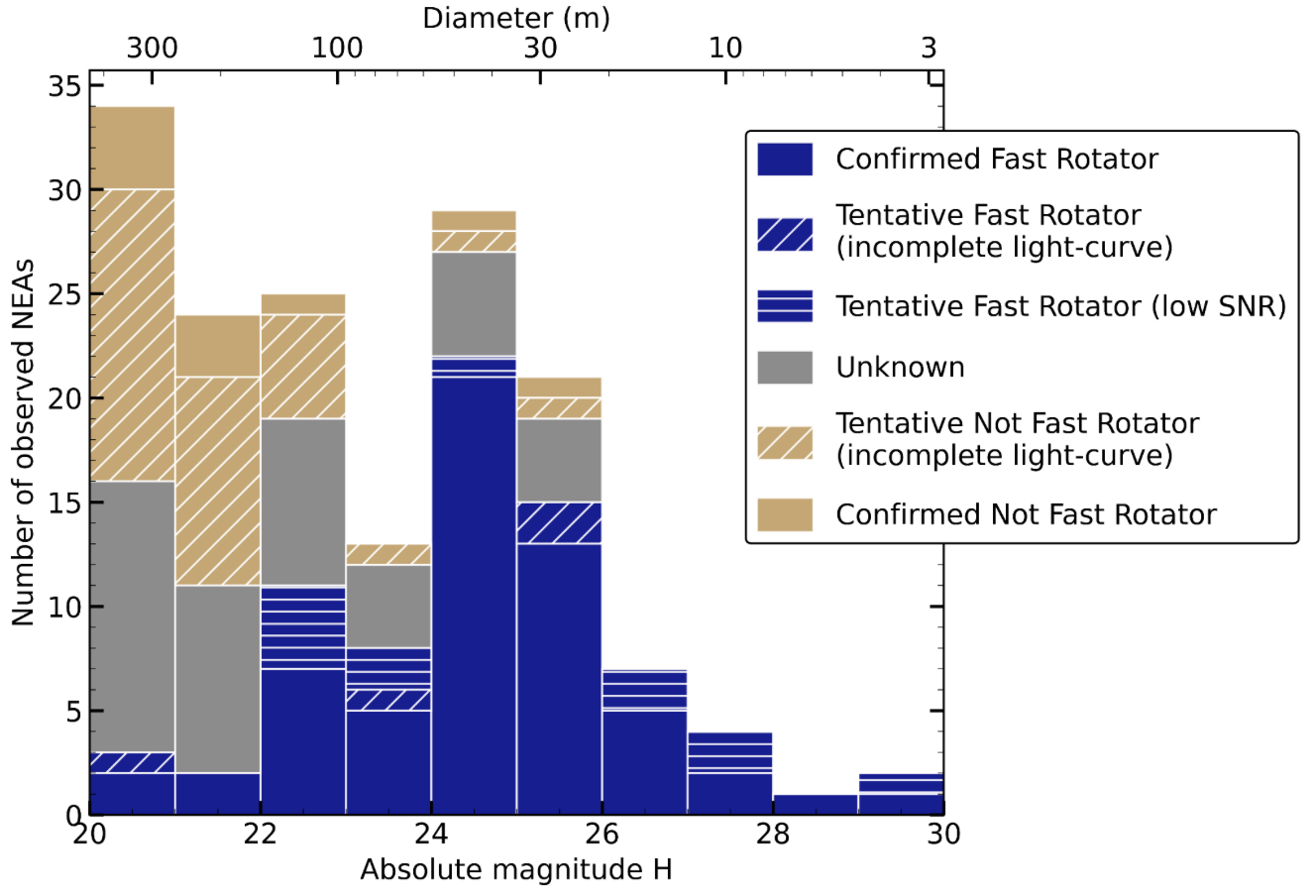

Figure 1. Number of small NEAs observed versus absolute magnitude, color‑coded by spin rate relative to the 2.2 h cohesionless spin barrier: fast rotators in blue and slower rotators in gold. Short observing blocks (< 2 h per target) reduce our capacity to determine to low‑amplitude, not-fast‑spinning objects.

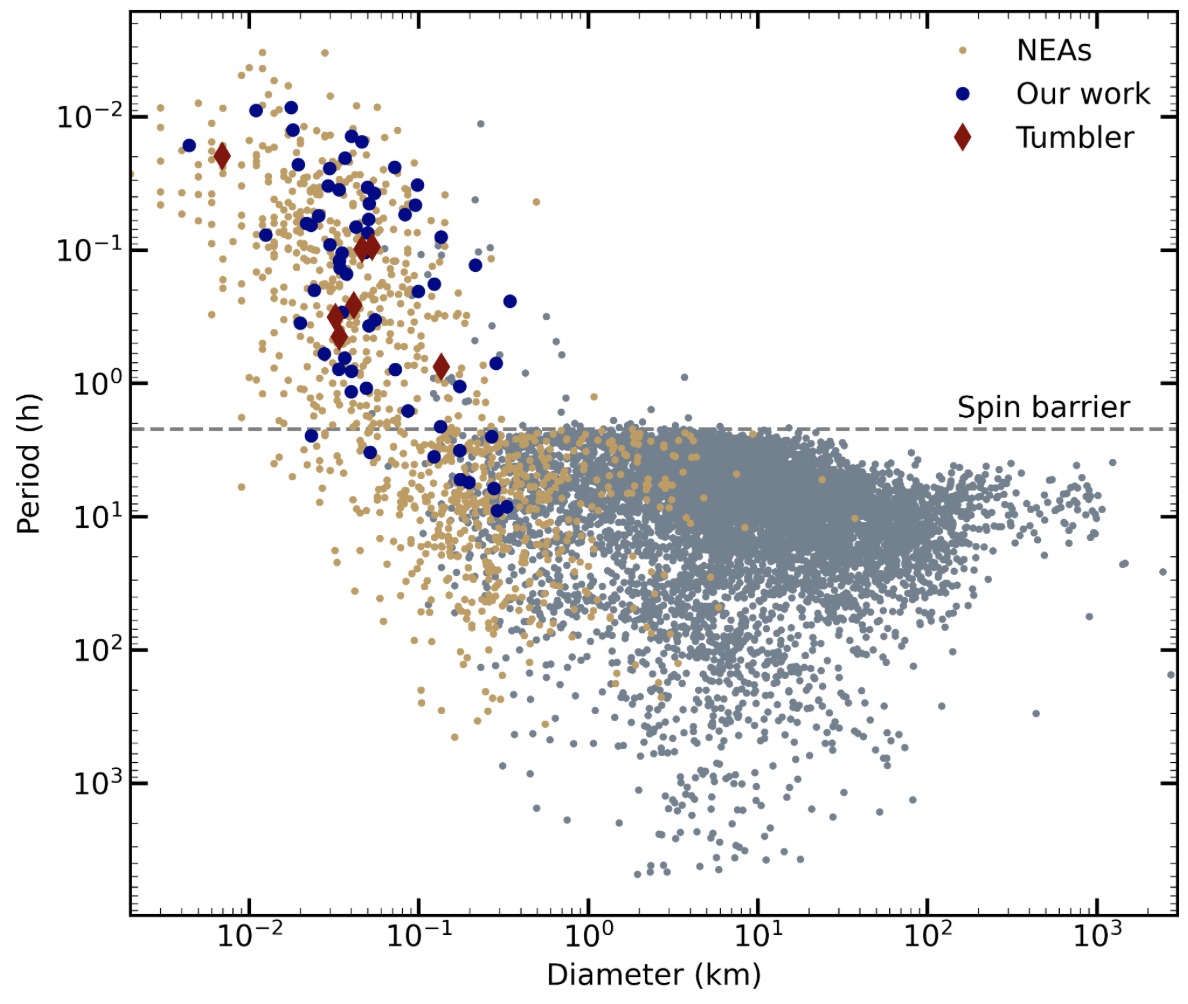

Figure 2. Published rotation periods versus diameter for asteroids (LCDB, U > 2), with Near‑Earth Asteroids highlighted in gold. Our new measurements appear in blue, with non‑principal‑axis (tumbling) rotators in red.

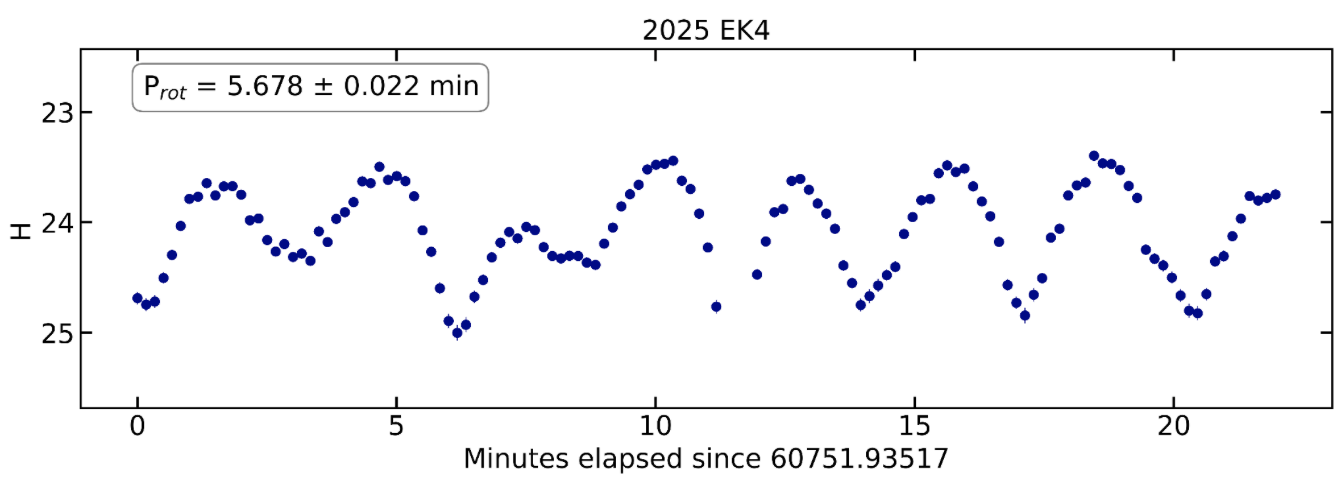

Figure 3. Lightcurve of 2025 EK4 over less than 25 minutes. This is one of the NEAs illustrating rapid, non‑principal‑axis rotation.

How to cite: R. Alarcon, M., Licandro, J., and Serra-Ricart, M.: Prevalence of Fast Rotators Among Small Near‑Earth Asteroids: An Ongoing Survey from the Two‑Meter Twin Telescope facility, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1464, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1464, 2025.

Introduction: L-type asteroids represent a rare taxonomic class that is spectrally similar to CO and CV carbonaceous chondrites [1]. Their spectra often suggest highabundances of refractory materials like calcium-aluminium-rich inclusions (CAIs), implying their parent bodies were among the earliest chondrites to form in the Solar System [2]. CO and CV chondrites in turn contain the highest vol% of refractory inclusions in the meteorite collection and are predominantly of petrographic type 3, with varying degrees of thermal metamorphsim [3]. Understanding the distribution and spectral characteristics of L-types is thus crucial for deciphering early Solar System composition and evolution. However, their rarity and spectral ambiguity with other classes have hindered comprehensive characterisation [4, 5]. Our study aimed to identify new L-types within known associated asteroid families, provide detailed UV-VisNIR spectral characterisation using VLT/XSHOOTER [6], assess the spectral diversity within the class, and investigate links to chondritic meteorites.

Methods: We obtained high-quality UV-VisNIR (0.30µm to 2.48µm) reflectance spectra of nine asteroids belonging to five families previously associated with L-types (Aquitania, Brangäne, Henan, Tirela, Watsonia [7, 8, 9]) using VLT/XSHOOTER. We classified them using different taxonomies [10, 11, 12] and compared them quantitatively with laboratory reflectance spectra of ordinary, CO, and CV chondrites [13, 14].

Results: Our observations successfully identified five new L-type asteroids, expanding the sample of this class with VisNIR wavelength coverage by ~30%. The remaining targets were classified as S-types. The new L-type spectra confirm the considerable spectral diversity previously noted for this population [12], often falling taxonomically between or on the edges of established classes (e.g., L, M, S) depending on the classification system and spectral features considered.

Combining our new data with existing VisNIR spectra of L-types and related "Barbarian" asteroids (polarimetrically defined and likely compositionally linked), we investigated the overall spectral distribution of this population. A potential bimodal distribution emerged, separating the L-type/Barbarian asteroids into two groups, tentatively named LL and LM. As illustrated by the mean spectra and albedos (see Figure 1), these groups primarily differ in their 2µm absorption band depth and geometric albedo: the LL group exhibits generally higher albedos and a more pronounced 2µm feature, while the LM group shows lower albedos and weaker spectral features, resembling M-type asteroids in overall shape but presenting subtle features. Notably, members from the same dynamical families (e.g., Aquitania, Brangäne) are found in both the LL and LM groups.

A similar analysis of laboratory spectra of CO and CV chondrites revealed analogous spectral diversity. CO chondrites, in particular, displayed a similar bimodal separation in spectral features and albedo (denoted here as “COr” and “COp” groups), mirroring the LL/LM asteroid split (Figure 1). CV chondrites also showed significant spectral variation across their subclasses (CVRed, CVOxA, CVOxB [15]), correlating feature strength with albedo. Comparisons suggest that the LL asteroids share spectral characteristics (stronger features, higher albedo) with COr and CVOxA chondrites, while the LM asteroids align better with the lower albedo, weaker-featured COp, CVRed, and CVOxB chondrites, once expected space weathering effects (primarily reddening) are considered [16, 17].

Figure 1: Reflectance spectra and albedo of CO-CV classes and subgroups and the two identified L-type populations. Shown are the mean values and the standard deviation in all wavelengths bins and the albedo distribution. The spectra are vertically offset for comparability.

Conclusions: The expanded census and detailed characterisation of L-type asteroids reveal a spectrally diverse population, likely sampling ancient parent bodies related to CO and CV chondrites. The observed spectral bimodality (LL/LM), mirrored in laboratory data for CO and CV chondrites, strongly suggests significant heterogeneity within the parent bodies of multiple asteroid families. This heterogeneity may stem from differing degrees of thermal metamorphism across the original planetesimals. The presence of members from the same dynamical family in both spectral groups further supports the concept of compositionally heterogeneous, yet related, L-type parent bodies.

The distinct UV-visible slope of L-types compared to S-types promises L-type identification in future Gaia data releases (e.g., DR4, mid 2026). The recently launched SPHEREx mission, providing near-infrared spectra, will be crucial for robustly testing the proposed bimodality, refining mineralogical interpretations, and fully characterising the distribution and nature of these enigmatic Solar System relics.

References:

[1] Burbine, T. H. et al., 1992, Meteoritics, 27, 424

[2] Sunshine, J. M. et al., 2008, Science, 320, 514

[3] Scott, E. R. D. & Krot, A. N. 2014, in Meteorites and Cosmochemical Processes, ed. A. M. Davis, Vol. 1, 65–137

[4] Devogèle, M. et al., 2018, Icarus, 304, 31

[5] Mahlke, M. et al., 2023, A&A, 676, A94

[6] Vernet, J. et al., 2011, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 536, A105

[7] Brož, M. et al., 2013, A&A, 551, A117

[8] Vinogradova, T. A. 2019, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

[9] Balossi, R. et al., 2024, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 688, A221

[10] Tholen, D. J. 1984, PhD thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson

[11] DeMeo, F. E. et al., 2009, Icarus, 202, 160

[12] Mahlke, M. et al., 2022, A&A, 665,A26

[13] Eschrig, J. et al., 2021, Icarus, 354, 114034

[14] Eschrig, J. et al., 2022, Icarus, 381 115012

[15] Bonal, L. et al., 2016, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 189, 312

[16] Lantz, C. et al. 2017, Icarus, 285, 43

[17] Mahlke, M. et al. 2024, Analogues of enigmatic L-types: The effect of space weathering on CV, CO, CK, and CL chondrites, EPSC 2024

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge important contributions by A. Aleón-Toppani to this work. This work was supported by the Programme National de Planétologie (PNP) of CNRS-INSU co-funded by CNES.

How to cite: Mahlke, M., Marsset, M., Devogèle, M., Baklouti, D., Beck, P., Bonal, L., Brunetto, R., Lantz, C., and Tanga, P.: In Barbarian territory: Spectral bimodality in L-type asteroids and their link to CO-CV chondrites, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1271, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1271, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

The FORCAST instrument on the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) regularly obtained mid-infrared data of large asteroids as calibrators for other observations. This previously unused dataset represents a long-baseline series of photometric and spectroscopic observations that can be used to investigate how thermal and compositional properties may change over time. We present multi-filter photometry and spectroscopy in the wavelength range 5-38 μm of (1) Ceres which was observed on seventeen nights between 2015-2022. These nights correlate to different portions of Ceres’ orbit (Figure 1). While there are no data near perihelion, the full data set covers a wide spread of Ceres’ orbit.

Figure 1. Location of Ceres along its orbital path (grey line) around the Sun (yellow star) for each of our observations (colored markers). Perihelion is marked with a black cross.

We performed aperture photometry on the imaging data, which consisted of between six and twelve different filters per night. We fit the Near-Earth Asteroid Thermal Model (NEATM) to the extracted photometric points to derive the beaming parameter (η), which is a proxy for thermal properties. We find that η does not change with Ceres’ point in its orbit or with the sub-observer longitude of the observation; however, we find a general increase in η over the time scale of our observations (Figure 2). The cause of this increase is likely instrumental, as it is also seen in a similar study of (4) Vesta.

Figure 2. We do not find a correlation between η and point in orbit or sub-observer longitude, indicating that there are no significant rotational or seasonal thermal effects on Ceres. We do see a correlation between η and julian date, which is likely an instrumental artifact.

Spectra between 17.6-37.1 μm were obtained on all nights, and additional spectra between 4.9-13.7 μm were obtained on three nights. The average spectrum (Figure 3) shows a broad feature near 20 μm due to phyllosilicates. We did not find any significant differences in the size or shape of this feature on any of the nights, indicating that it does not vary rotationally or seasonally. Ceres' lack of rotational and seasonal changes enables it to be a good calibrator for other astronomical observations, as expected.

Figure 3. Average spectrum of Ceres from all seventeen nights of data.

How to cite: Arredondo, A., Deleon, A., Becker, T., and McAdam, M.: Long-term MIR photometry and spectroscopy of (1) Ceres from SOFIA, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1824, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1824, 2025.

Main belt asteroid 203 Pompeja shows evidence of spectral variability in the visible and near-infrared (VNIR). During most epochs, Pompeja’s spectrum resembles a typical X-type asteroid [1, 2]. However, during its 2021 apparition, steeply red sloped spectra were observed in the VNIR, invoking comparisons to the ultra-red VR and RR TNOs and leading to the suggestion that Pompeja may have migrated from the TNO region to the Main Belt [3]. An uneven distribution of ultra-red material across its surface may contribute to Pompeja’s observed spectral variability.

In order to assess the extent of ultra-red material across Pompeja’s surface, in October 2024, we observed this asteroid using the Las Cumbres Observatory global telescope network [4], obtaining grizy photometry over nearly its entire 24 hour rotational period. The observing geometry relative to the earth and Sun during this epoch was close to equatorial, providing nearly-complete longitudinal coverage of Pompeja at low and mid-latitudes. We present the results of this observing campaign and discuss their implications for the abundance and distribution of ultra-red material on Pompeja in light of current models of its shape and rotational pole orientation [5]. We derive upper limits on the abundance of ultra-red material at equatorial and mid-latitudes, discuss the implications of our observations on the origin of Pompeja, and evaluate future observational prospects.

[1] Hasegawa, S., DeMeo, F. E., Marsset, M., et al. 2022 ApJL, 939, L9, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac92e4

[2] Humes, O. A., Thomas, C. A., & McGraw, L. E. 2024, PSJ, 5, 80, doi: 10.3847/PSJ/ad2e99

[3] Hasegawa, S., Marsset, M., DeMeo, F. E., et al. 2021 ApJL, 916, L6, doi: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac0f05

[4] Brown, T. M., Baliber, N. et al. 2013 PASP, 125, 931, 1031-1055, doi: 10.1086/673168

[5] Humes, O. A., Hanuš, J. 2024 PSJ, 5, 271, doi: 10.3847/PSJ/ad8f3a

How to cite: Humes, O. and Thomas, C.: 24 hours on Pompeja: time-resolved spectrophotometry of an unusual Main Belt asteroid, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-523, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-523, 2025.

Binary asteroids provide a unique opportunity to study the key physical and dynamic properties of small solar system bodies. Unlike single bodies, binaries allow us to estimate component masses and orbital parameters based on mutual orbital dynamics. This provides constraints on system architecture and formation mechanisms. These systems are particularly valuable for testing evolutionary scenarios in which a rapidly rotating progenitor undergoes rotational fission, followed by binary reaccumulation of the fragments into a bound system.

Among the known formation pathways, YORP-induced rotational fission is expected to operate more efficiently for small asteroids near the Sun, whereas collisional formation dominates larger bodies. Theoretical time-scale comparisons suggest that these two mechanisms become equally effective at around 6 km in diameter (Jacobson et al. 2014), which closely matches the size of (7344) Summerfield (D = 6.25 km; NEOWISE). The asteroid’s rotation period of ~2.6 hours (Pray et al., 2017, CBET 4412) is slightly above the spin barrier (~2.2 hours), which is consistent with a history of rotational acceleration. Although a collisional origin cannot be ruled out, the mass ratio of ~0.18 is consistent with the observed limit for binaries formed by rotational fission (q < 0.2; Pravec et al. 2010). Near this threshold, fission events may be especially violent, allowing for slightly slower rotation than the critical value.

(7344) Summerfield lies near the critical boundaries where rotational fission might just be able to form a binary system, making a good candidate to evaluate this mechanism. To investigate this possibility, we conducted a photometric study of (7344) Summerfield, a confirmed main-belt binary chosen for its previously reported periodic brightness variations and potential mutual events, high visibility, and favorable photometric amplitude under our observing conditions.

We conducted observations using the 1.8 m Bohyunsan Optical Astronomy Observatory (BOAO), the 0.6 m Sobaeksan Optical Astronomy Observatory (SOAO), and the 1.0 m Lemmonsan Optical Astronomy Observatory (LOAO) from February to April 2025. We employed R-band time-series photometry for this study. This multi-site approach improved the system’s temporal resolution and phase coverage across its rotation.

Initial analysis reveals a rotation period of approximately 2.59 hours, with mutual events manifesting as characteristic brightness dips. We measured an eclipse depth of 0.04 magnitudes (~3.7% brightness decrease), corresponding to a radius ratio of ~0.19 between the two components. These values are consistent with those reported independently by Pray et al. (2017, CBET 4412), which further supports the binary nature of the system.

Assuming that (7344) Summerfield is an S-type asteroid, we use a bulk density of 2700 kg/m^3, which is typical for this class (Carry 2012), and we assume that both components are spherical. We then estimate the component masses as ~3.5 × 1014 kg for the primary and ~2.4 × 1012 kg for the secondary. Using the orbital period of P=17.41 hr from CBET 4412 and applying Kepler’s third law, we estimate the system’s semi-major axis to be approximately 13 km. This value is consistent with the ~11 km estimate reported in the Asteroids with Satellites Database (Johnston’s Archive), considering large uncertainties in shape and bulk density. We measured a lightcurve amplitude of 0.177 magnitudes for the primary. Assuming a prolate shape (a ≥ b ≃ c), and applying the relation a/b = 10^(0.4A) (Binzel et al. 1989), we calculate an elongation ratio of a/b ≈ 1.18, which indicates that the primary has a low degree of elongation. This shape is characteristic of primaries formed via rotational fission, which evolve toward a top-shape due to reaccumulation and spin-driven relaxation.

Studying additional binary systems near the critical thresholds for rotational fission, such as (7344) Summerfield, through systematic photometric surveys would enable a statistical characterization of their properties. This approach could significantly advance our understanding of how rotational fission contributes to the formation and dynamical evolution of binary asteroids in the main belt.

How to cite: Kim, H., Kim, M.-J., Lee, H.-J., JeongAhn, Y., Moon, H.-K., Choi, Y.-J., and Kim, Y.: Time-Series Photometry of Main-Belt Binary Asteroids: A Case Study of (7344) Summerfield, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-2054, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-2054, 2025.

Introduction

Small planetary bodies, such as asteroids, have surfaces covered with loose granular material known as regolith. This regolith can flow under disturbances from impacts, tidal interactions, or spin variations caused by thermal torques. The complex gravity field, irregular shape, and potentially three-dimensional rotation of these bodies affect how the regolith flows across the surface.

We propose a framework to investigate regolith dynamics on small planetary bodies, such as asteroids, over long timescales, focusing on their impact on the body's spin and shape evolution. We begin by examining the idealized case of axisymmetric regolith motion, followed by a generalization to the more complex non-axisymmetric scenario.

Methodology

We assume that the regolith movement is triggered by impact events that induce seismic shaking on the asteroid's surface. To simulate the stochastic history of these collisions, we employ the size frequency distribution of the main asteroid belt. While the majority of the collision energy contributes to crater formation, a smaller portion is transmitted as seismic waves. We propose that regolith flow initiates when seismic waves produce stress levels that surpass the material’s cohesion and hydrostatic compression. Once movement begins, we assume the regolith remains fluidized as long as seismic shaking continues on the asteroid. Our regolith flow model incorporates a rotating frame to account for the asteroid's spin, curvilinear coordinates to capture complex topography, and mass loss from the surface.

Asteroids typically have irregular shapes, yet top shapes are in plenty. Top shapes can be thought of as minor deviations from a sphere. With this inspiration, we envision the central body to be a sphere with shallow topographical features on its surface that evolves after each landslide. We finally augment the landslide model with the Monte-Carlo collisional history of an asteroid and stochastic thermal/YORP (Yarkovsky–O'Keefe–Radzievskii–Paddack) torque.

Axisymmetric motion

Regolith motion is neither global nor symmetrical. However, the current section assumes axisymmetric nature of regolith motion to reduce the complexity of the mathematical equations involved.

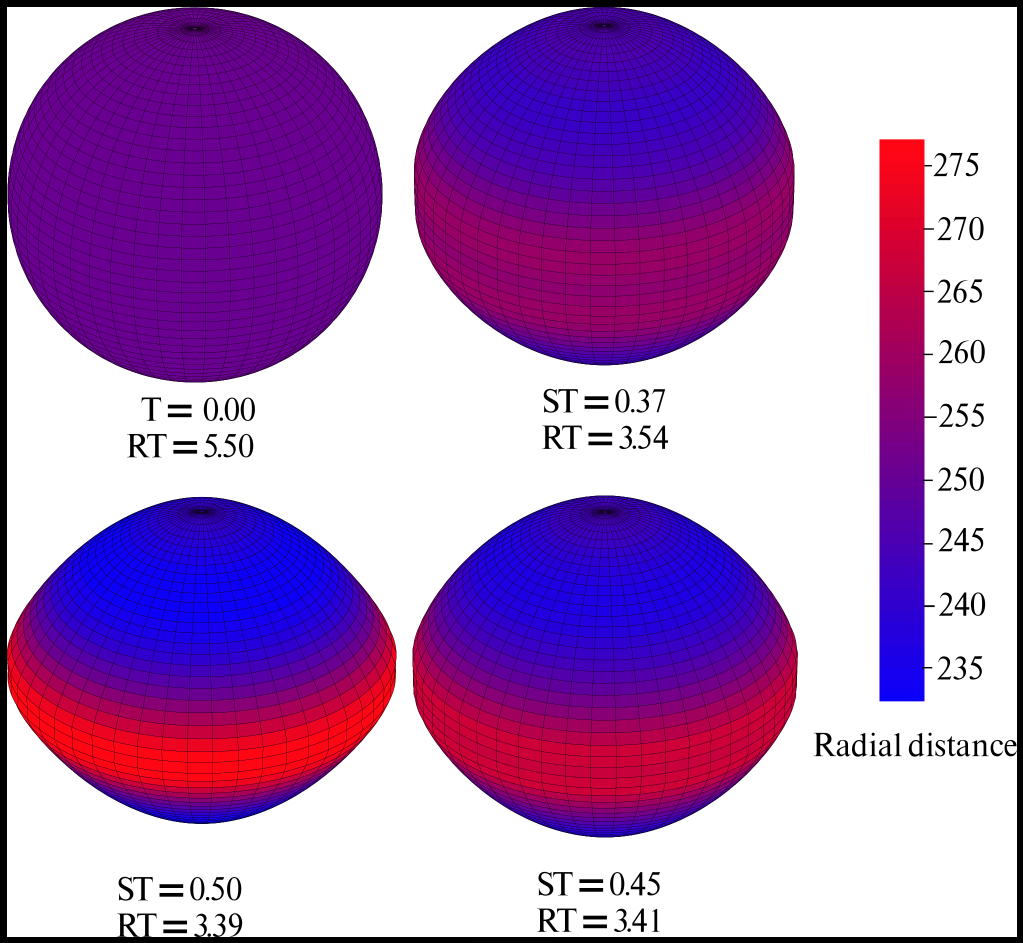

Figure 1 illustrates the shape evolution of an initially spherical asteroid. Under the influence of a spin-increasing YORP torque, impact-induced landslides drive gradual surface reshaping, causing the asteroid to slowly transform into a top-like shape.

Figure 1: The evolution of shape of an initially spherical asteroid. ST is the simulation time and RT is the rotational time period. Radial distance is the distance of the point from the center of the sphere.

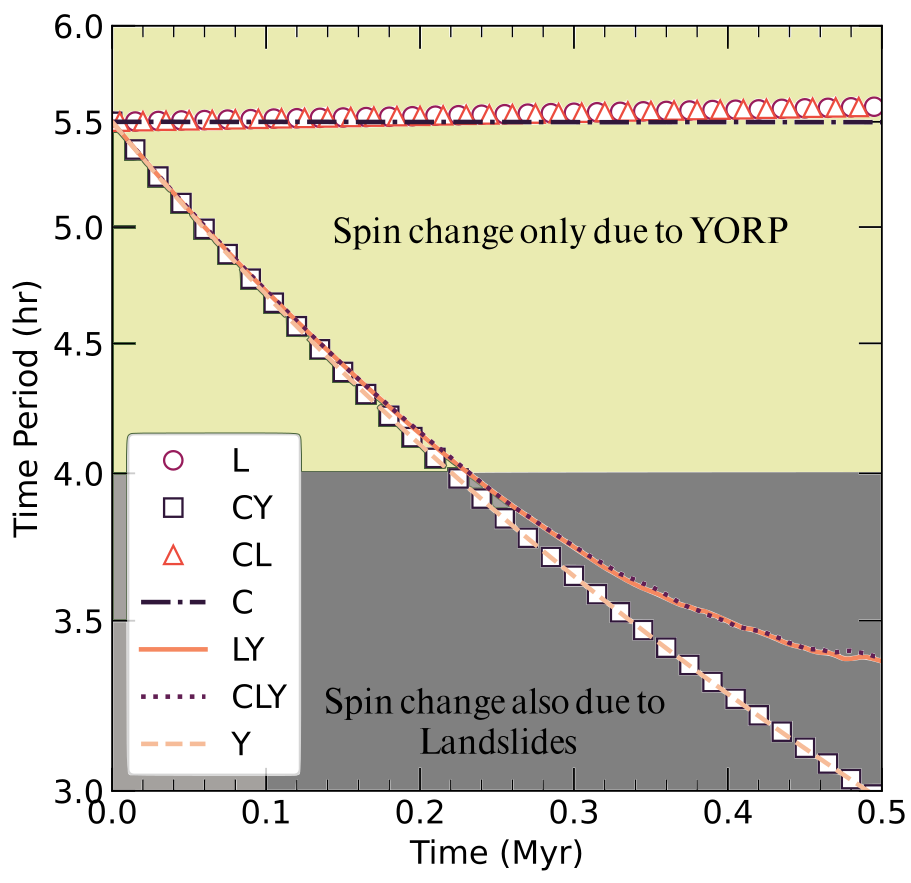

The effects on spin change due to various active processes are shown in Fig. 2. shows the spin change when different processes were considered such as collision (C), YORP torque (Y) and surface landslides (L). We found that the impact induced landslides can contribute to spin change only at high rotation rates (or small rotation periods).

Figure 2: Spin evolution resulting from collisions (C), YORP torque (Y), and surface landslides (L), with all possible combinations of these processes illustrated

Non-axisymmetric landslides

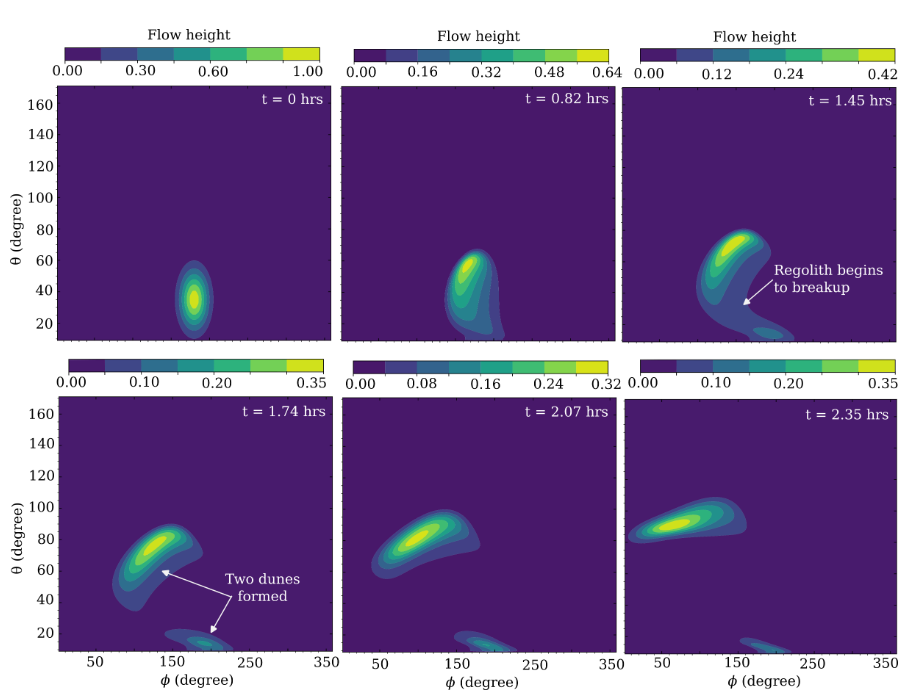

Non-axisymmetric regional scale landslides represent a more realistic scenario. On a fast rotating asteroid, the Coriolis force will dominate the regolith migration. To illustrate this, the slumping of an idealized Gaussian dune on a frictionless spherical asteroid is shown in Fig. 3. In the absence of rotation the dune should slump gradually and its peak remains at the same spot, as gravity is normal to the surface. However, due to rotation, the centrifugal force moves the peak towards the equator while the Coriolis force moves it westward. As the dune reaches the equator, it slows down and begins spreading in the azimuthal direction.

Figure 3: The slumping of a Gaussian dune on a frictionless spherical asteroid. θ is the meridional direction and Φ is the azimuthal direction.

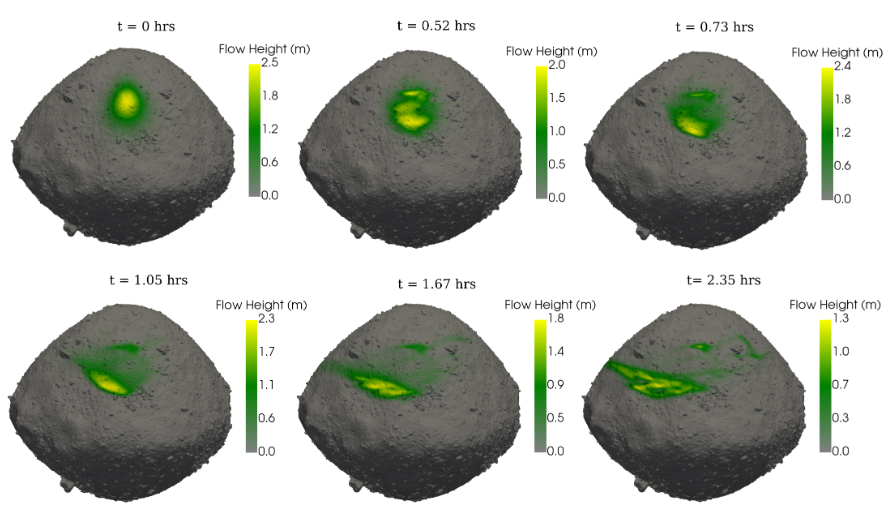

Finally, we simulate dune slumping on a Bennu-shaped asteroid rotating with a short period of 3.4 hours, as shown in Figure 4. Our results show that the regolith does not reach the equator. The prominent equatorial bulge of Bennu acts as a barrier, hindering the material’s movement toward the equator. At such high rotation rates, some of the material begins to lift off the surface and enter orbit

Figure 4: The slumping of a dune on a Bennu-shaped body.

Conclusion

We introduce a framework for analyzing regolith motion on asteroid surfaces, incorporating various active processes affecting the body. We demonstrate its application in an idealized scenario involving axisymmetric regolith flow and find that such motion becomes prominent at high rotation rates, significantly influencing the spin and shape of small planetary bodies. The framework is then extended to model dune slumping in non-axisymmetric cases, including asteroids with shapes similar to Bennu.

How to cite: Gaurav, K. and Sharma, I.: Regolith dynamics and long term surface evolution on asteroids, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1810, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1810, 2025.

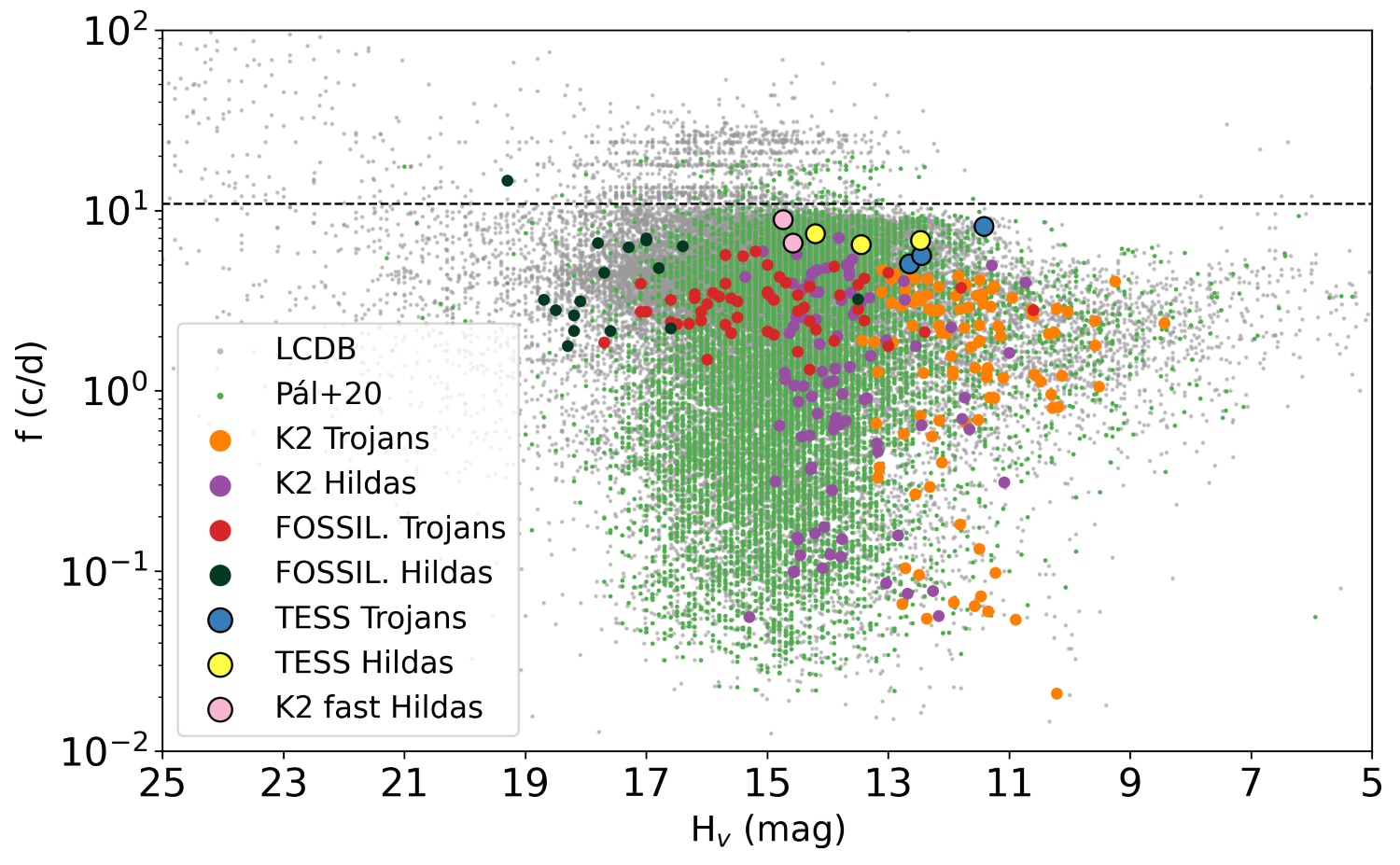

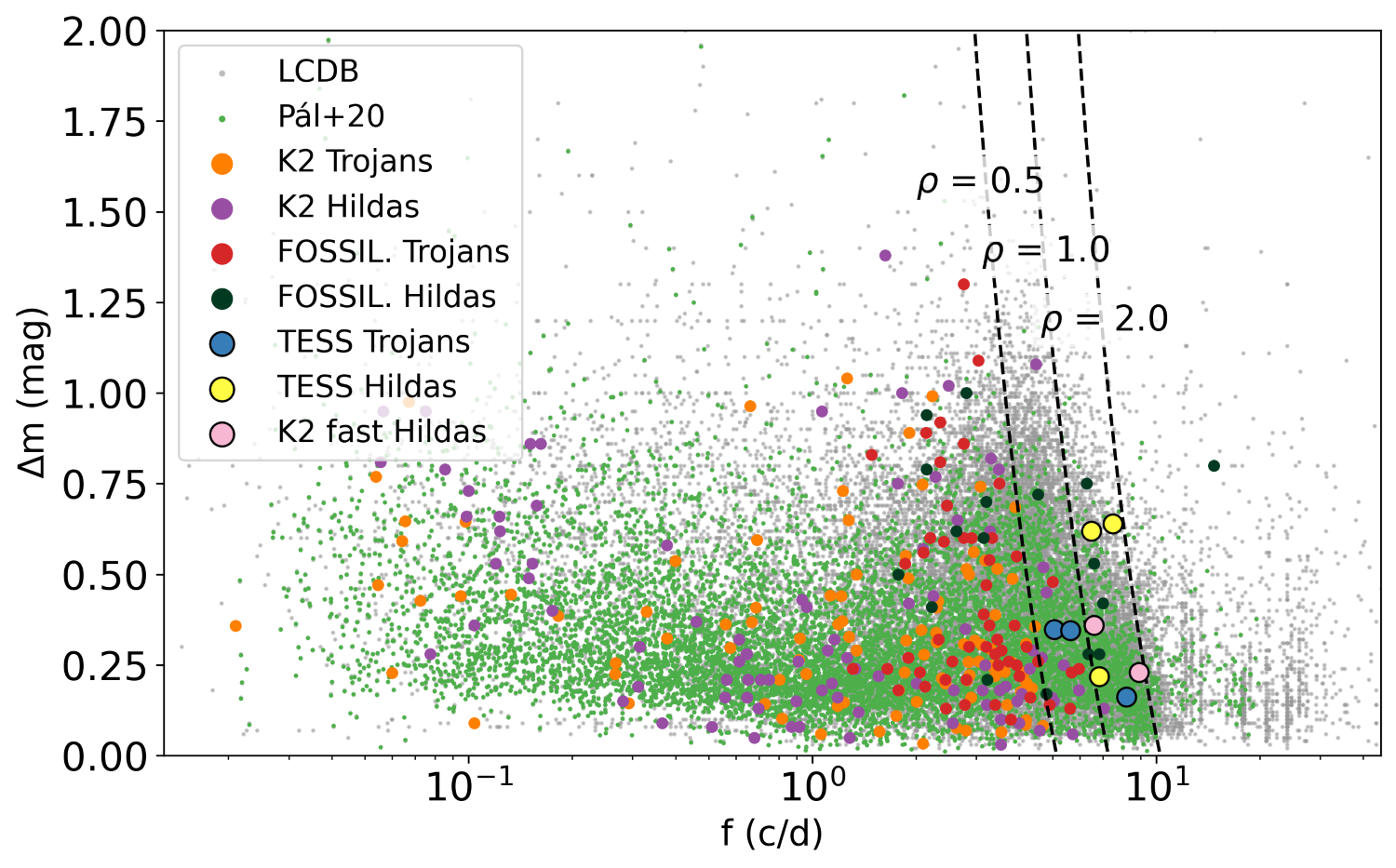

The rotational characteristics of small bodies in the Solar System serve as critical constraints on their internal structure, composition, and collisional evolution[1,2]. The break-up rotation rate of asteroids defines an upper bound on their bulk density or necessary cohesion if they are to remain gravitationally bound. While most medium-sized Hilda and Jovian Trojan asteroids exhibit relatively slow rotation, recent observations with the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) reveal a handful of exceptions that stretch the boundaries.

We present the discovery and analysis of the three fastest-spinning Hilda asteroids and the three fastest-spinning Jovian Trojans identified. These findings provide new constraints on the bulk densities and required cohesion for structural integrity in these populations.

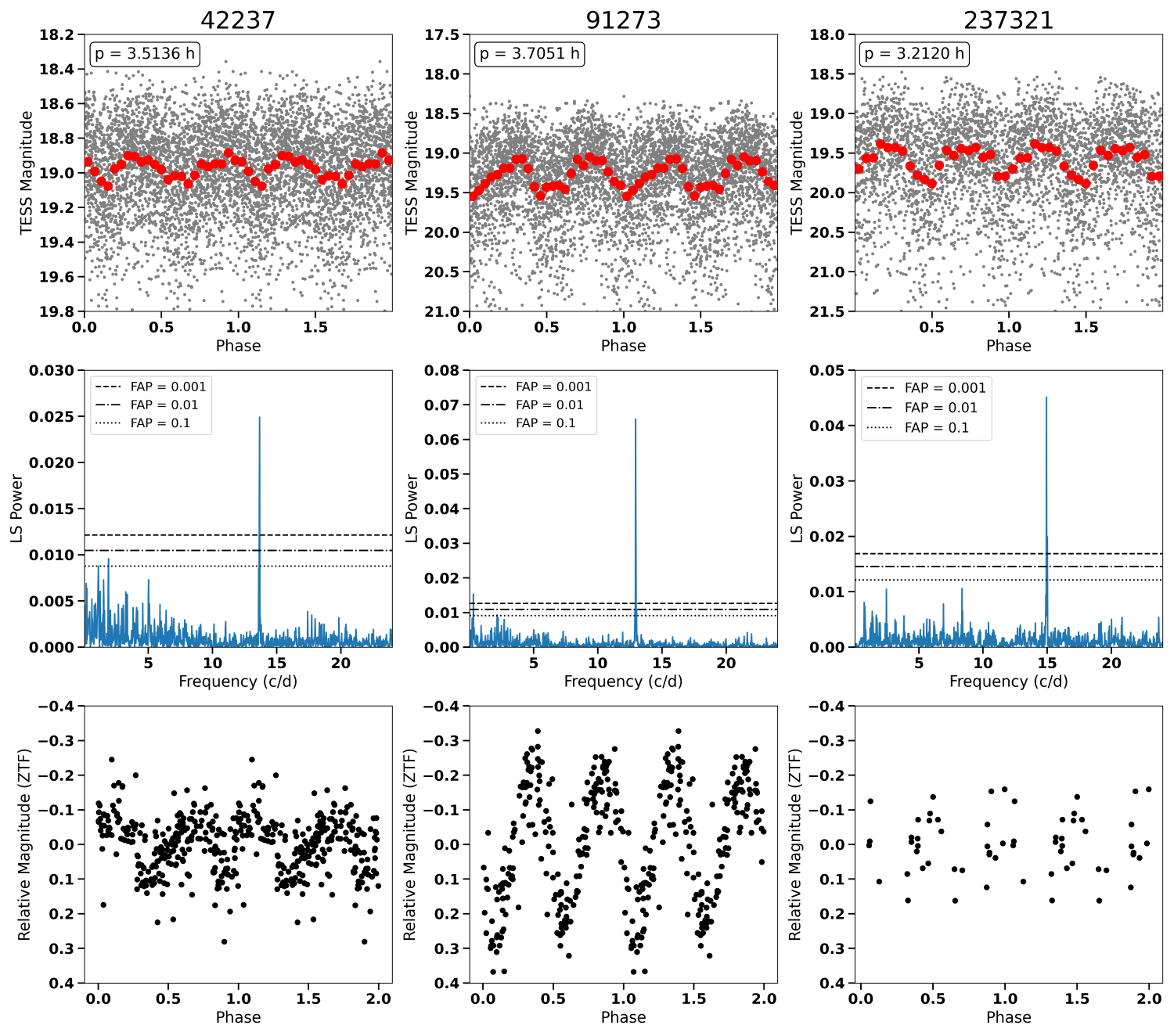

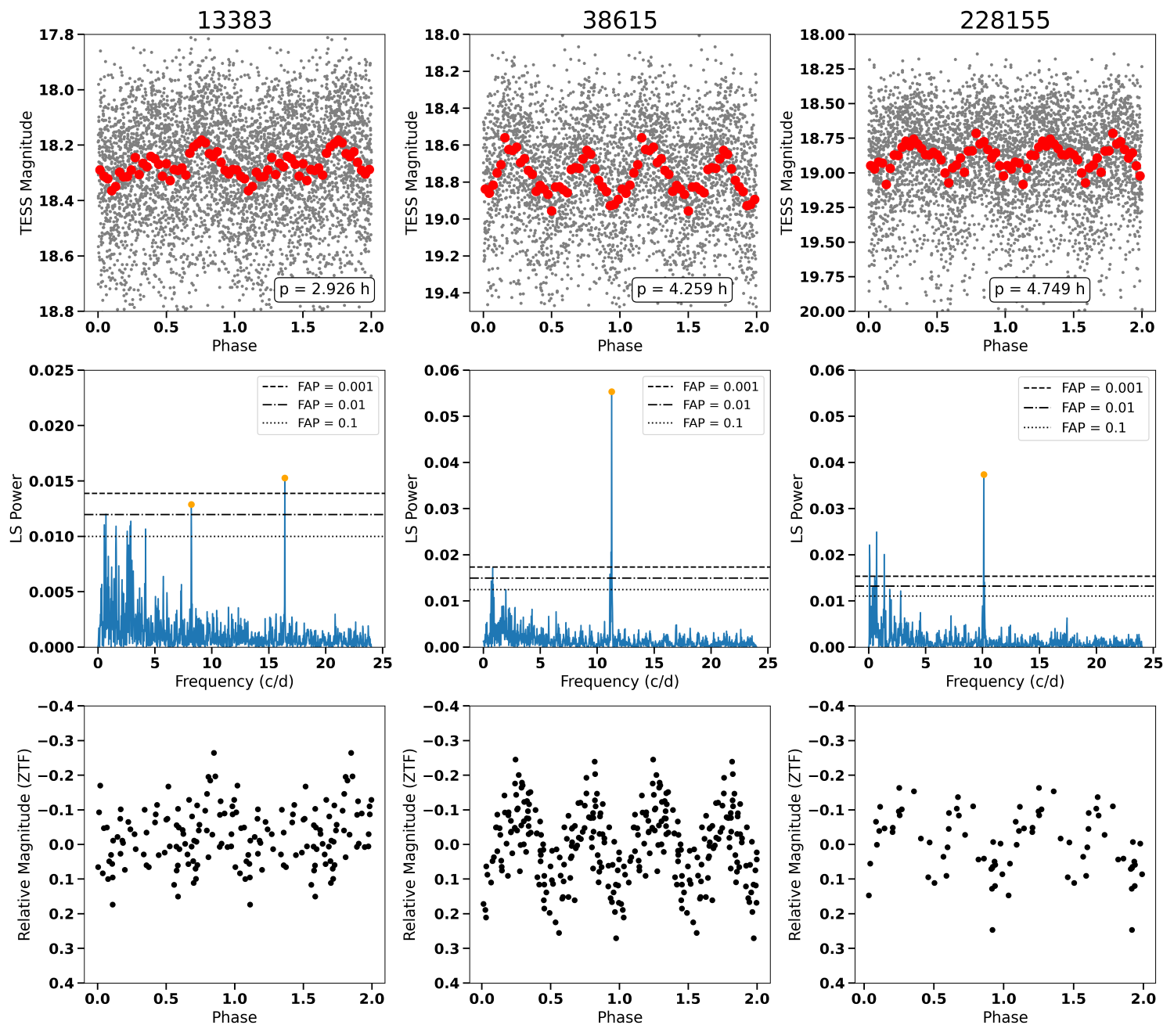

Our analysis is based on TESS photometric light curves processed using refined techniques for asteroid photometry, including adaptive aperture photometry and correction for systematics and background contamination[3]. For all targets, rotation periods were confirmed using Lomb-Scargle periodograms and Fourier series fits, with additional validation from Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) data when available. Physical parameters were derived assuming triaxial ellipsoid shapes, with estimates of cohesion based on the Drucker–Prager failure criterion.

Among Hildas, we identified three asteroids — (42237), (91273), and (237321) — with rotation periods in the 3.2–3.7 hour range, well below the previously established ~5-hour threshold for this population. Two additional fast rotators from the K2 mission were reanalysed using TESS data. These objects exhibit light curve amplitudes between 0.2 and 0.5 mag and diameters ranging from 7 to 19 km. The implied densities, assuming a strengthless structure, span 1.1–1.9 g/cm³. For the largest asteroid in the sample, cohesion of ~1–3 kPa is required for densities below 1.5 g/cm³.

Figure 1. Folded TESS light curves and corresponding rotational frequency spectra for the three fast-rotating Hilda asteroids on the left three panels and the three fast-rotating Jovian Trojan asteroids on the right three panels. Top panels: phase-folded light curves using the derived rotation periods, with observations binned into 24, 26, and 22 bins for (42237), (91273), and (237321), respectively and with 36 phase bins in the case of (13383), (38615), and (228155). Middle panels: Lomb-Scargle power spectra with dashed lines indicating false alarm probability levels. Bottom panels: independent light curves from ZTF, folded with the same rotation periods for comparison.

For Jovian Trojans, we report fast rotation in three ~15–24 km bodies: (13383), (38615), and (228155), with periods of 2.926, 4.259, and 4.749 hours, respectively[4]. Notably, (13383) rotates significantly faster than the nominal ~5-hour breakup limit for Trojans, requiring a density of ~1.6 g/cm³ or cohesion exceeding several kPa. The other two Trojans imply lower critical densities (~0.7–0.8 g/cm³), consistent with the traditionally assumed porous, icy rubble-pile structures.

The obtained rotation periods and the derived densities are presented in Fig. 1, together with data from large databases, including Jovian Trojans and Hildas from the K2 mission, and the FOSSIL survey.

Figure 2. Rotational properties of inner Solar System asteroids. The top panel shows rotational frequency versus absolute magnitude, with the dashed horizontal line indicating the traditional rotational breakup limit corresponding to a 2.2 hours of period. The bottom panel plots light curve amplitude against rotational frequency, with dashed curves representing lines of constant critical density. Colored points denote asteroids from various observational surveys. The three Hilda asteroids are shown as large yellow symbols, the fast-spinning Jovian Trojans are highlighted in blue and pink symbols represent two previously known fast-rotating Hildas from the K2 mission.

The occurrence of fast rotators among Hildas (~1\%) is notably higher than among Jovian Trojans, possibly reflecting a higher fraction of denser C-type asteroids within the Hilda population. A two-component Maxwellian distribution model incorporating a fast-rotating C-type subpopulation among Hildas supports this interpretation. In contrast, most Jovian Trojans are D-types with lower densities and porosities that preclude such fast spins without significant internal strength.

The extreme spin rate of (13383), paired with its relatively high albedo (~0.11), may indicate a collisional spin-up event that exposed bright material at the surface. This, along with its elevated density requirement, challenges the notion that all Jovian Trojans are loosely bound, low-density remnants of the outer Solar System.

Our results expand the known rotational parameter space of both Hilda and Jovian Trojan asteroid populations. These fast-spinning objects provide rare insights into the material properties and evolutionary histories of small Solar System bodies beyond the main belt. Continued TESS monitoring and complementary surveys (e.g., ZTF, LSST) will be essential for building statistically meaningful samples of fast rotators in resonant populations.

References:

[1] Mottola, S., Britt, D. T., Brown, M. E., et al. 2024, Space Sci. Rev., 220, 17

[2] Vokrouhlický, D., Nesvorný, D., Brož, M., et al. 2025, arXiv e-prints, arXiv:2503.04403

[3] Takács N., Kiss C., Szakáts R., Pál A., 2025, PASP, 137, 044401

[4] Kiss, C., Takács, N., Kalup, C. E., et al. 2025, A\&A, 694, L17

How to cite: Takács, N., Kiss, C., Szakáts, R., Plachy, E., Kalup, C. E., Szabó, G. M., Molnár, L., Sárneczky, K., Szabó, R., Bódi, A., and Pál, A.: Probing Internal Structure Through Extremes: The Fastest Rotators Among Hilda and Jovian Trojan Asteroids, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-266, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-266, 2025.

Context

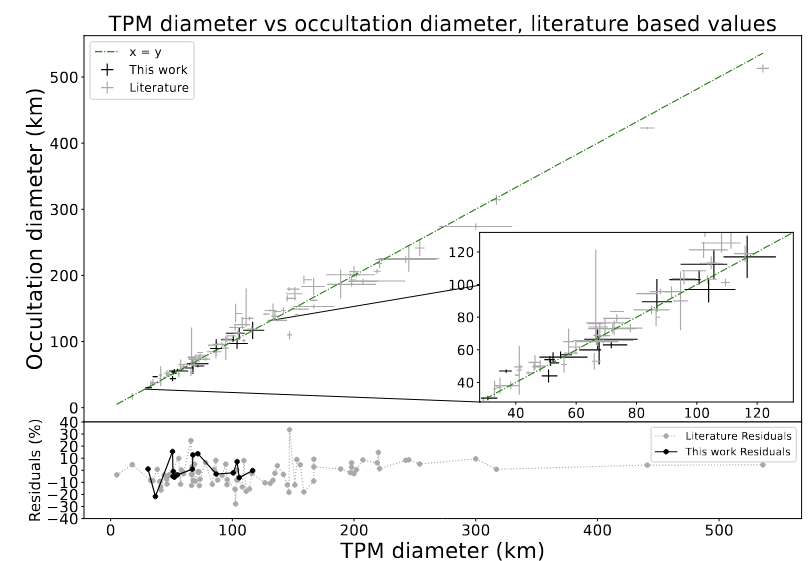

Reliable asteroid diameters underpin accurate studies on other topics like determination of the density. Traditional diameter estimates—often based on simplistic spherical models or/and on data of lower quality, can differ by tens of percent in the literature, propagating into density uncertainties exceeding 90%. On the other hand, the convex inversion thermophysical model (CITPM) (see Durech et al. 2017) is an advanced thermophysical model that simultaneously fits lightcurves and thermal-infrared data enabling precise size determination.

Aim

We aim to demonstrate that CITPM alone can yield main-belt asteroid diameters with precision comparable to multichord stellar occultations. Our goal is to determine diameters of fifteen slowly rotating, low-amplitude asteroids using CITPM, and to validate these results against occultation-based values (see our poster from Marciniak et al. for full details on occultations).

Methods

Starting from dense, multi-apparition lightcurves, we derive convex 3D shape and spin models via lightcurve inversion (see Kaasalainen, Torppa 2001, Kaasalainen et al. 2001). These models feed directly into CITPM, which optimizes shape parameters together with thermal inertia, albedo, surface roughness and diameter by fitting both visible and infrared datasets. We then compare our CITPM diameters to diameters determined by occultations (see Marciniak et al. poster) and to literature values, quantifying agreement and demonstrating CITPM standalone accuracy.

Results

For all fifteen targets, CITPM-derived diameters agree with occultation-based values to within 5%. Overall, CITPM residuals relative to occultations are smaller than those found in the literature, underscoring the advantage of simultaneous lightcurve–thermal fitting. Moreover, CITPM rely solely on photometry and thermal-IR measurements. This validates CITPM as a powerful, widely applicable tool for future large-scale asteroid size surveys. All results from this work can be found in Choukroun et al. (accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics).

Figure 1: Representation of diameters from TPMs on the x-axis and diameters from occultations on the y-axis. Grey points correspond to values from the literature, while black points represent values from this work. The green line corresponds to y = x.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the grant 2020/39/O/ST9/00713 funded by National Science Centre, Poland.

References

Choukroun, A., Marciniak, A., Durech, J., et al., accepted to A&A

Durech, J., Delbo., M., Carry, B., Hanuš, J., & Alí-Lagoa, V. 2017, A&A, 604, A27

Kaasalainen, M. & Torppa, J. 2001, Icarus, 153, 24

Kaasalainen, M., Torppa, J., & Muinonen, K. 2001, Icarus, 153, 37

How to cite: Choukroun, A., Marciniak, A., Durech, J., and Perła, J.: Asteroid sizes determined with thermophysical model, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-123, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-123, 2025.

The temporary exposure of volatiles on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, driven by sublimation-induced erosion, has been extensively discussed in previous studies. Bright spots observed on the surface have been attributed to the appearance of water ice [1, 2, 3]. These ice exposures, or bright features, were detected in optical OSIRIS/NavCam images through time-series analysis, appearing as high-albedo spots in several geomorphological regions. Temperature and spectral analyses of data from the VIRTIS-M instrument further confirmed the presence of water ice. Subsequent research [4] revealed a broad spatial distribution of these bright features. Notably, surface exposure of volatiles is not unique to 67P but has also been observed on other comets, such as 9P/Tempel 1 [5].

The formation of these bright spots on the surface of 67P may be the result of sublimation-driven erosion, likely involving subsurface volatiles. Mapping studies [4] and our own findings suggest a concentration of bright spots in the equatorial region, with a slight shift towards the southern hemisphere. These spots are predominantly located in rugged terrains with consolidated material. Additionally, the locations of faint jet outbursts and previously detected jets near the perihelion may be associated with some of these bright spots.

Albedo variation, a key parameter for detecting bright spots, was analyzed using the single-scattering albedo derived from the radiance factor and illumination data from OSIRIS images. By applying the algorithm from [6] and the Hapke reflectance model, we were able to extract albedo variations, revealing local discrepancies between the target features and the surrounding surface. Time-series analysis of the OSIRIS dataset confirmed the presence of numerous bright spots, supporting the hypothesis that these features result from sublimation-driven erosion, although the underlying physical processes may vary.

In our study, we focus on the microphysical processes that could lead to temporary increases in surface brightness. We introduce a novel heat transfer model for the near-surface layer, grounded in the medium’s microphysical properties [7]. This model consistently accounts for various heat transfer mechanisms, the permeability of the crust to gas flow, and other relevant factors. For the first time, we propose an evolving layer model that predicts the 'oscillating' behavior of the crust, where phases of accumulation (thickening) and discharge alternate repetitively.

In addition to the above model, we also examine the evolutionary model [8], which investigates the erosion of a heterogeneous layer composed of small ice particles and dust. This model introduces a unique approach to describing the evolution of such a mixture, providing estimates for both the removal of dust particles—while preserving exposed ice regions—and the formation of a temporary dry crust.

The computational experiments performed in our study allow for a comparison between the lifetime of bright spots and observational data. This provides us with quantitative constraints on the microscopic properties of the near-surface material.

References: [1] Pommerol A et al. (2015) A&A, 583, A25. [2] Barucci M. A. et al. (2016) A&A, 595, A102. [3] Filacchione G. et al. (2016a) Nature, 592, 7586, 268-372. [4] Deshapriya J. D.P. et al. (2018) A&A, 613, A36. [5] Sunshine J. M. et al. (2006) Science, 311, 5766, 1453-1455. [6] Davidsson B. J. R. et al. (2022) MNRAS, 516, 4, 5125-5142. [7] Xin Y. et al. (2025), A&A, 693, A123. [8] Schuckart , C. and J. Blum (2025) A&A, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202553750

How to cite: Skorov, Y., Krasilnikov, S., Xin, Y., Wu, B., and Blum, J.: Albedo Variations and Bright Spot Formation on Comet 67P: Microphysical Scenarios, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-197, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-197, 2025.

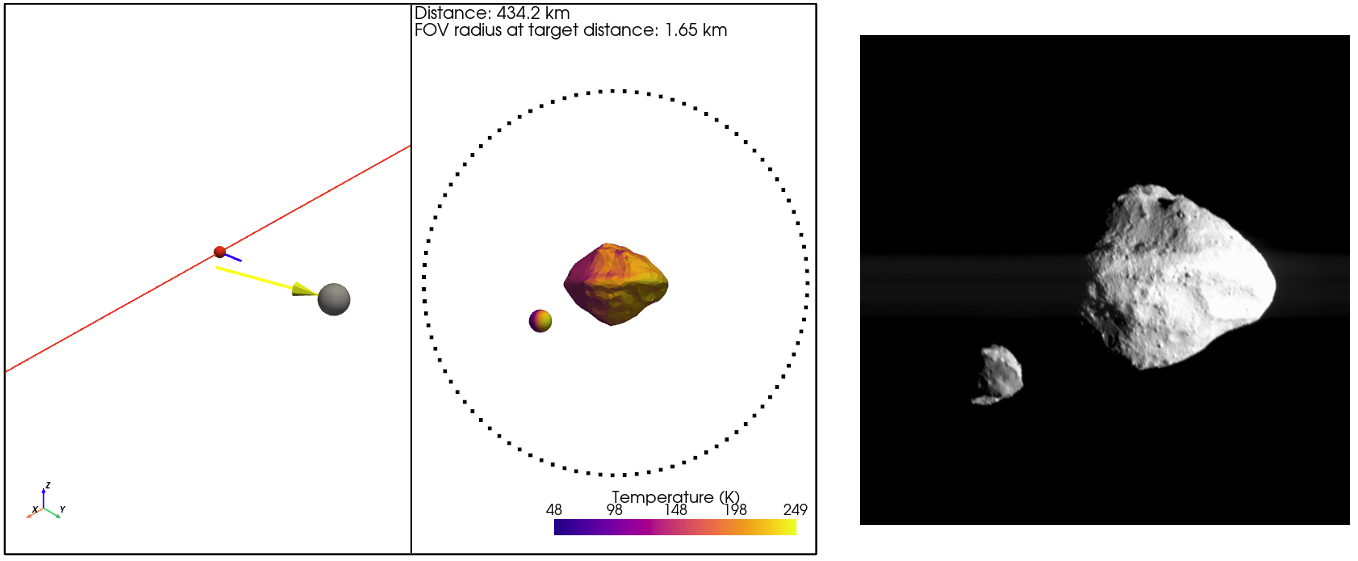

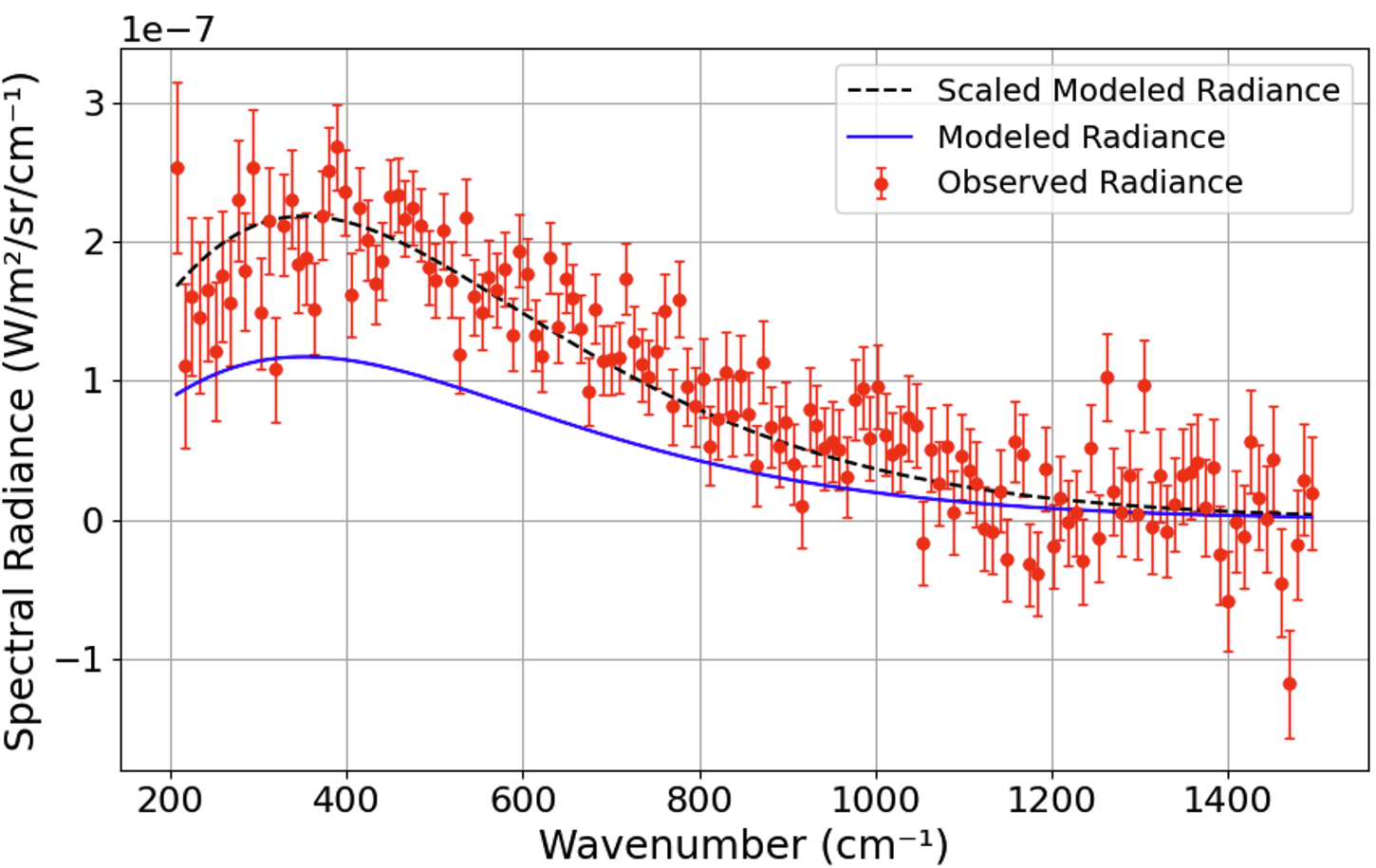

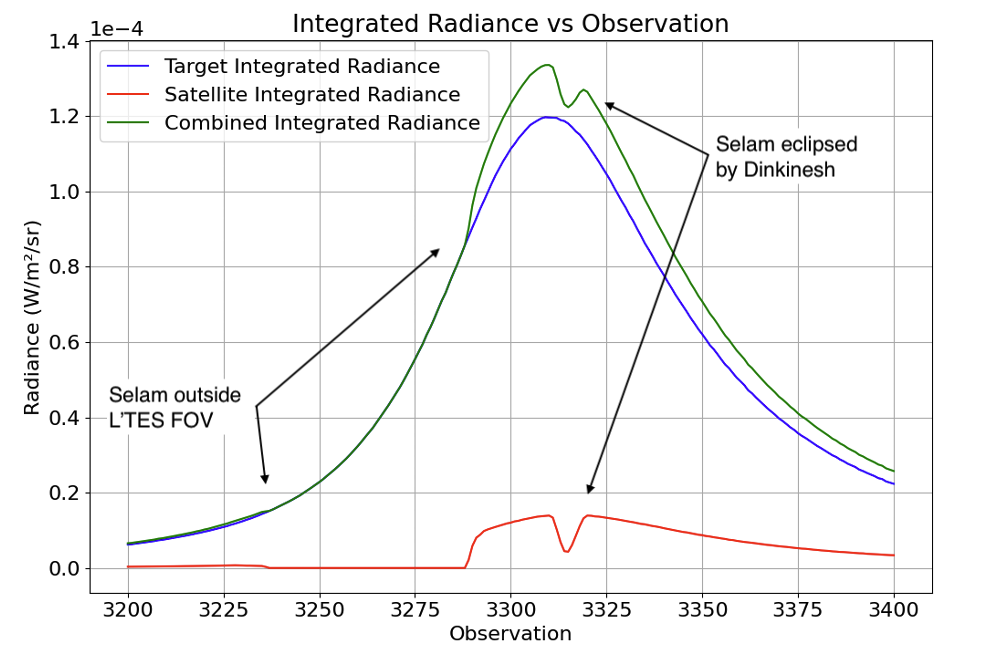

Introduction: The Lucy mission's first asteroid flyby provided a unique and unexpected opportunity to study a binary asteroid system up close. Originally expected to encounter a single target, Dinkinesh, the discovery of its small, tidally locked moon, Selam, introduced additional opportunity and complexity to the interpreting flyby observations [1]. We present thermal modelling of the binary system, quantifying how the presence of Selam influenced radiance measurements and indicating its possible impact on thermal inertia estimates. Thermal inertia (TI) offers insight into surface properties such as grain size and regolith structure. Determining the TI of Dinkinesh adds to our understanding of small S-type asteroids and enables comparison within a binary, potentially revealing differences driven by tidal effects or surface evolution.

Methods: We modelled the flyby geometry and instrument measurements using the new TESBY (Thermal Emissions Spectrometer flyBY) module of TEMPEST (the Thermophysical Equilibrium Model for Planetary Environment Surface Temperatures) [2] to simulate the thermal radiance of both bodies and assess their combined effect on interpretation of data from the Lucy Thermal Emission Spectrometer (L’TES) instrument [3].

The Thermal Model: Dinkinesh and its satellite, Selam, were modelled in TEMPEST. A stereo-photogrammetric shape model is available for the primary target – Dinkinesh [4], with ~2 m lateral and ~0.5 m vertical resolution, covering ~60% of the surface. This shape model was downsampled to a dimensionally accurate model with 1266 facets with a resolution of ~35 m. A sphere of representative diameter (230 m [1]) was used for the satellite Selam.

Figure 1: TESBY visualization of flyby. Global view of the flyby trajectory (left), and the FOV of the instrument (centre), with corresponding L’LORRI image for comparison [1] taken 0.54 minutes before closest approach (right). Input is the TEMPEST [5] result for the shape model of Dinkinesh, and representative diameter sphere for Selam. Parameters used: solar distance = 2.19 AU, rotation periods = 3.74 hours (Dinkinesh) and 52.7 hours (Selam) [1] thermal inertia (provisional) = 40 J m-2 s-1/2 K-1, geometric albedo = 0.27

Flyby geometry: Building on the TEMPEST framework, the TESBY module is given the geometry information for the flyby and the thermal data from TEMPEST. Based on the 7.3 mrad Field-of-View (FOV) of the L’TES instrument [3] TESBY produces simulated radiance measurements by computing a weighted sum of blackbody curves from each visible facet, based on its temperature, projected area, and emission angle. Matching these modelled radiances to the instrument data allows us to fit for the thermal inertia of the asteroid. A complicating factor in this study is that the sensitivity of L’TES is not uniform across its FOV, including this effect in the model is the subject of ongoing work.

Figure 2: Preliminary modelled radiance results (blue line) compared to L’TES observation (red) using the same model settings as Fig. 1. Scaled radiances (dotted line) are also provided (see main text for more information).

Results: An example of the currently predicted model radiance is given by Figure 2. As it shows, there is a notable offset between the predicted and observed radiances. Accounting for the position of the targets in the L’TES FOV is expected to resolve the observed discrepancy in absolute radiance levels. However, as the scaled model shows, the predicted radiances are able to capture the shape of the L’TES radiance.

We find that due to the slower rotation rate of Selam, the maximum surface temperatures on the satellite can be as much as 25 K higher than those on Dinkinesh (Fig. 1), meaning that despite the small size (lobe diameter of only 230 m, compared with 790 m for Dinkinesh [1]), the contribution to measured radiance is significant. This effect is highlighted by investigation of the integrated radiances of the targets throughout the flyby (Fig. 3), where the entry and exit of Selam within the FOV is visible, as well as the dip in integrated radiance while Selam is partially eclipsed by Dinkinesh. Our results demonstrate the importance of considering the full system in flyby analysis, informing techniques for similar encounters in the future. This work highlights how the thermal signature of even a small secondary body can significantly impact observations, shaping our understanding of asteroid surface properties and thermal environments.

Continued analysis will focus on the use of TEMPEST/TESBY to constrain the thermal inertia of this binary asteroid from L’TES flyby observations.

Figure 3: Variation in integrated wavelength for Dinkinesh (target, blue), Selam (satellite, red) and combined effect (green). Radiances were integrated over the 200–1500 cm⁻¹ spectral range. The results show that despite its small size, Selam makes a significant difference to the spectral radiance, particularly at shorter wavelengths. The dip in combined spectral radiance at observations 3315-3320 is due to Selam being eclipsed by Dinkinesh.

The thermal model code is open source and available at: github.com/duncanLyster/TEMPEST/

Acknowledgement: This work was made possible by support from the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council.

References:

[1] Levison, H.F., Marchi, S., Noll, K.S. et al. A contact binary satellite of the asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh. Nature 629, 1015–1020 (2024).

[2] Lyster, D., Howett, C., & Penn, J. (2024). Predicting surface temperatures on airless bodies: An open-source Python tool. EPSC Abstracts, 18, EPSC2024-1121.

[3] Christensen, P. R., et al. The Lucy Thermal Emission Spectrometer (L’TES) Instrument, Space Sci. Rev. (2023)

[4] Preusker, F. et al. (2024). Shape Model of Asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh from Photogrammetric Analysis of Lucy’s Frame Camera L’LORRI. 55th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Abstract #1903.

[5] Lyster, D., Howett, C., & Penn, J. (2025). TEMPEST: A Modular Thermophysical Model for Airless Bodies with Support for Surface Roughness and Non-Periodic Heating. Submitted to EPSC Abstracts, 2025

How to cite: Lyster, D., Howett, C., Spencer, J., Emery, J., Byron, B., Christensen, P., Hamilton, V., and Lucy Team, T.: Thermal Modelling of the Flyby of Binary Main Belt Asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh by NASA’s Lucy Mission, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-546, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-546, 2025.

Introduction: Near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) like Itokawa and Eros provide invaluable insights into the collisional and surface evolution of the inner solar system. These bodies, classified as S-type asteroids, are particularly abundant in the inner asteroid belt and are believed to retain signatures of collisional events that have shaped their surfaces over time. Once exposed, these surfaces undergo space weathering (SW), a gradual alteration process caused primarily by solar wind irradiation and micrometeorite bombardment. Since the progression of SW is time-dependent, it offers a means of estimating the surface exposure age of an asteroid following a resurfacing event. Determining the SW age of NEAs like Itokawa and Eros can thus provide critical constraints on their geologic history, regolith dynamics, and collisional evolution.

Aim: This study aims to estimate the surface exposure ages of Itokawa and Eros by analyzing their reflectance spectra using a machine learning approach that captures the spectral alterations due to SW.

Methods: We employed an ensemble machine learning model, trained on laboratory reflectance spectra of irradiated silicate samples. These samples, comprising olivine, pyroxene, olivine-pyroxene mixtures, and chondritic meteorites, simulate the mineralogy typically found on S-type asteroid surfaces. Spectral data were sourced from the Reflectance Experiment Laboratory (RELAB), published literature, and direct contributions from authors.

The model’s inputs included reflectance spectra and corresponding SW conditions (micrometeorite impact dose and solar wind flux), while the output was the exposure time at 1 AU. Itokawa's surface-resolved spectral data were acquired by the Near Infrared Spectrometer (NIRS) aboard the Hayabusa spacecraft (Abe et al. 2011). Eros data were obtained by the Near-Infrared Spectrometer (NIS) on the NEAR Shoemaker spacecraft (Warren et al. 1997). All asteroid data were retrieved from the NASA Planetary Data System (PDS). The spectra were interpolated from 820–2080 nm range at 20 nm intervals for Itokawa and 820–2360 nm, at 20 nm intervals for Eros, as required by the model. The model predictions were subsequently corrected for heliocentric distance to reflect actual surface ages.

Results: The surface age estimates for Itokawa range from approximately 2 × 103 to 2 × 109 years (Fig 1). Both solar wind irradiation and micrometeorite impacts contributed to surface alteration, though solar wind effects were found to be more dominant. In contrast, Eros shows evidence of much older surfaces, with estimated surface ages ranging from 4 × 10⁸ to 2 × 10⁹ years (Fig 2), largely driven by micrometeorite impacts. However, the spectral resolution of the Eros dataset was notably lower than that of Itokawa, introducing greater uncertainty in the model’s predictions for Eros.

Discussion and conclusion: The relatively young surface ages of Itokawa (2.8 × 103 years) align well with findings from the Hayabusa sample return mission, and other studies, which revealed that the dominating SW agent is solar wind irradiation (Hiroi et al. 2006, Matsumoto et al. 2016, Keller et al. 2016, Burges et al. 2021, Sunho et al. 2022). This supports the hypothesis that Itokawa has undergone frequent resurfacing events, possibly due to regolith migration (Miyamoto eta al. 2007), tidal resurfacing (Binzel et al. 2010), or by seismic shaking (Tsuchiyama et al. 2011). However, our study also reveals that certain regions of Itokawa (e.g., Arcoona) exhibit mature surface ages, dominated by micrometeorite impacts, reaching up to 2 × 10⁹ years, suggesting localized areas of minimal resurfacing and long-term exposure. The mature surface ages for Eros, consistent with previous spectral studies and surface morphology analyses, suggest a mature surface (Mahlke et al. 2022, Korda et al. 2023). Eros appears to lack significant recent resurfacing activity, allowing prolonged micrometeorite bombardment to dominate its SW history. Relatively younger ages can be observed in crater regions. This may be due to the material movement on the crater slope (Mantz et al. 2004) or it may reflect the cratering event age.

The contrasting surface ages and dominant SW processes between Itokawa and Eros underscore the role of asteroid size, orbital dynamics, and regolith properties in governing SW rates. While smaller asteroids like Itokawa are dynamically active and frequently refreshed, larger bodies like Eros tend to preserve ancient surface features. Additionally, Itokawa’s contact binary origin may contribute to more recent reshaping events, which could explain the presence of localized areas with younger surface ages. Our results demonstrate the utility of machine learning in decoding the complex interplay between spectral alteration and exposure history.

Fig 1. Predicted surface age for asteroid Itokawa.

Fig 2. Predicted surface age for asteroid Eros.

Abe et al. 2011 Data set information

Binzel et al. 2010 DOI 10.1038/nature08709

Burges et al. 2021 DOI 10.1111/maps.13692

Hiroi et al. 2006 DOI 10.1038/nature05073

Keller et al. 2016 https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20160002375

Korda et al. 2023 DOI 10.1051/0004-6361/202346290

Mahlke et al. 2022 DOI 10.1051/0004-6361/202243587

Matsumoto et al.2016 DOI 10.1016/j.icarus.2015.05.001

Miyamoto eta al. 2007 DOI 10.1126/science.1134390

Sunho et al. 2022 DOI 10.1051/0004-6361/202244326

Tsuchiyama et al. 2011 DOI 10.1126/science.1207794

Warren et al. 1997 DOI 10.1023/A:1005015719887

How to cite: Palamakumbure, L. and Kohout, T.: Surface age of the asteroids Itokawa and Eros by machine learning., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-274, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-274, 2025.

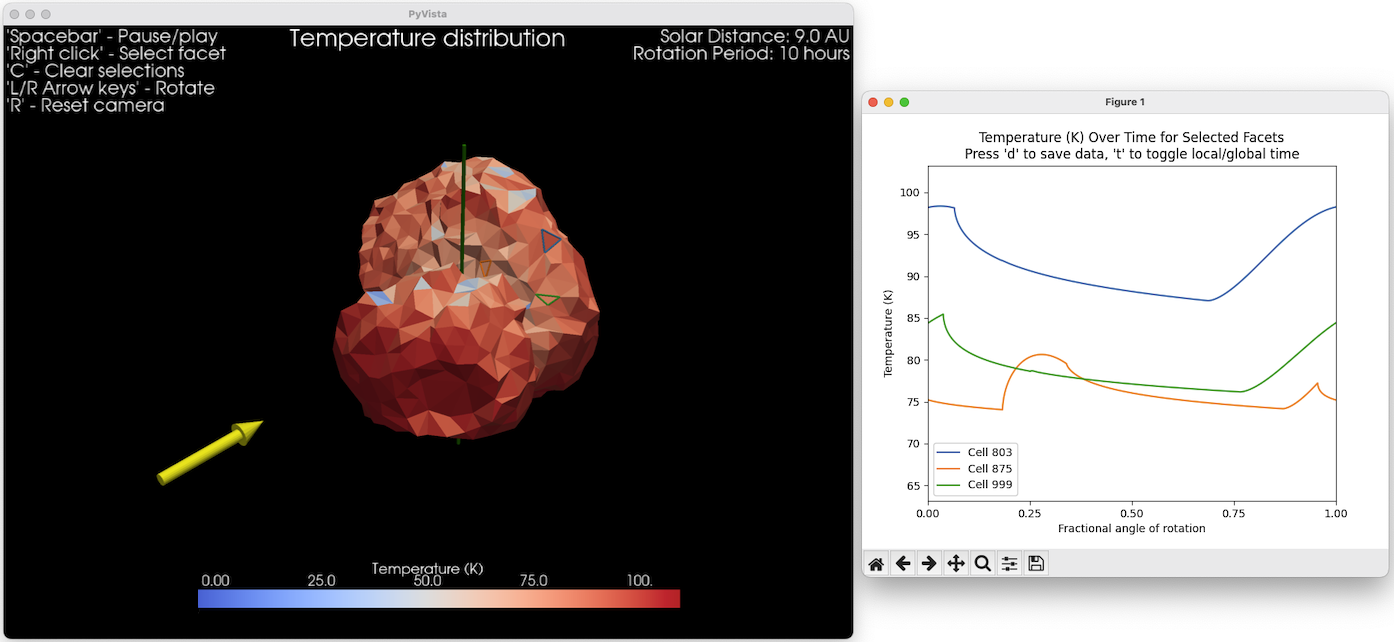

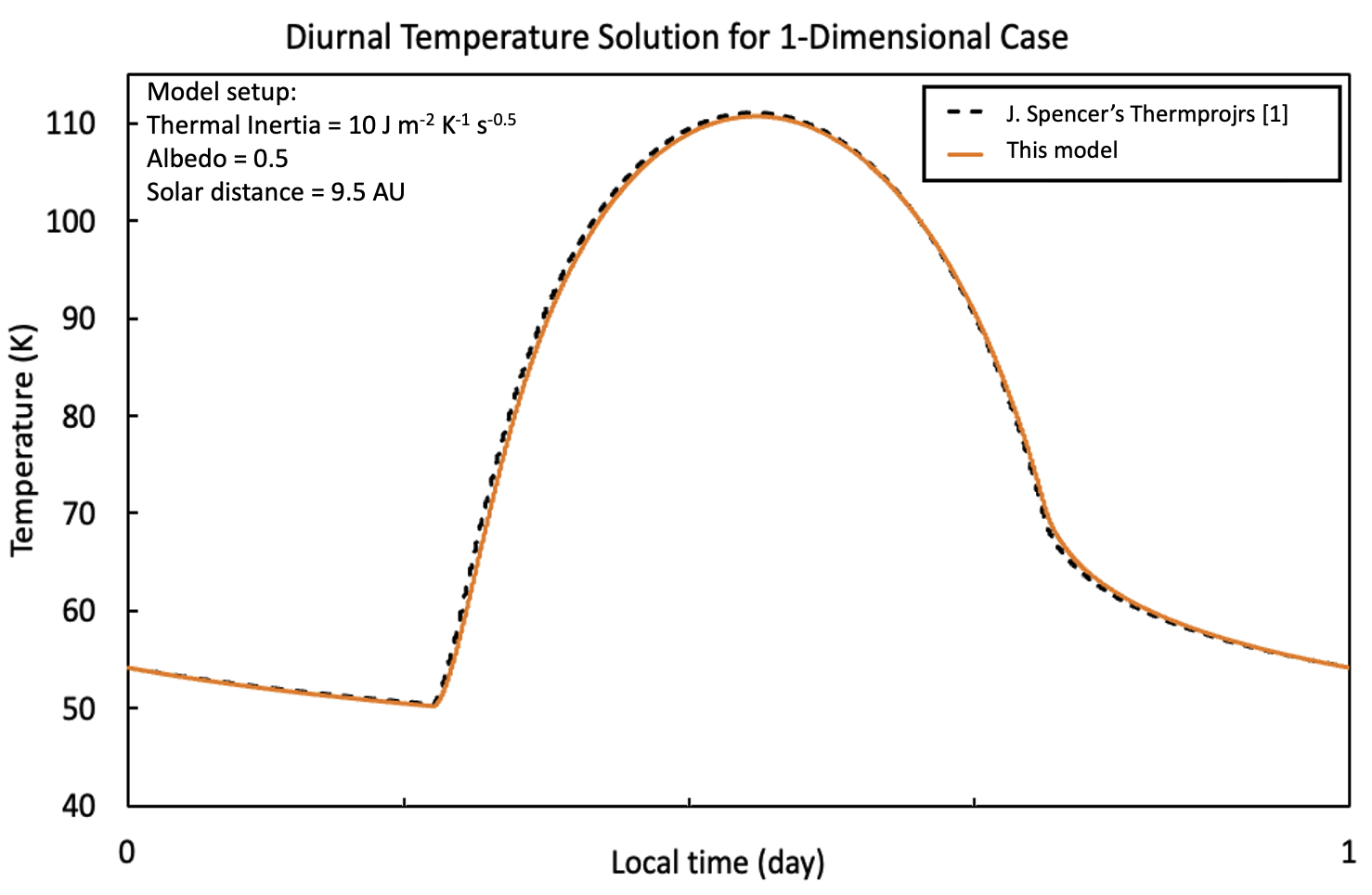

Introduction: Understanding surface temperatures on airless planetary bodies is crucial for interpreting thermal observations and constraining surface properties. We present TEMPEST (Thermal Evolution Model for Planetary Environment Surface Temperatures), a modular, open-source Python model that simulates diurnal and non-periodic thermal evolution on irregular bodies. Unlike traditional 1D periodic solvers, TEMPEST handles transient heating events such as eclipses, non-synchronous rotations such as tumbling asteroids, and seasonal variations. Key capabilities include surface roughness modelling via hemispherical craters, multiple thermal conduction schemes, and modular scattering using lookup tables (LUTs). TEMPEST has been used to analyse data from the Lucy mission and has been validated against the well-established Spencer 1D thermal model, thermprojrs [1].

Figure 1: TEMPEST allows the user to select a facet to view any of its time varying properties including insolation, temperature and radiance. The diurnal temperature curves (right) are those of the corresponding outlined facets selected by the user in the interactive pane (left).

Methods: TEMPEST calculates surface temperatures by solving a surface energy balance that includes solar flux, thermal emission, vertical heat conduction, and (optionally) radiative self-heating. Figure 1 shows the user interface once the model has completed a run. Key components include:

- Thermal solvers: Includes a standard 1D periodic conduction scheme influenced by the widely used thermprojrs [1] and a non-equilibrium solver, designed for better performance and stability in non-periodic cases.

- Scattering treatments: Utilises precomputed LUTs for various scattering laws (e.g., Lambertian, Lommel-Seeliger). This structure allows users to incorporate empirical bi-directional reflectance function (BRDF) data (e.g., from goniometer measurements of lunar regolith) or test the impact of different scattering assumptions, which can be particularly important for investigating the temperature of shadowed regions, as shown in Figure 2. The modularity also facilitates user modification for specific research needs.

- Surface roughness: Implemented via hemispherical sub-facet craters with adjustable rim angle to match roughness with a specified RMS slope angle.

- Non-periodic and time-dependent conditions: Supports time-dependent boundary conditions, including periodic scenarios such as eclipses and seasonal variations due to orbital eccentricity, as well as non-periodic cases including tumbling rotation, endogenic heating, and, or other user-defined transient heating scenarios.

Designed for efficient parallel execution, the model runs effectively on multi-core personal computers and can efficiently simulate shape models with tens of thousands of facets. It has also been deployed on high-performance computing clusters for larger-scale models on the order of 1 million facets. Input configuration files are simple and flexible, allowing integration into larger analysis pipelines.

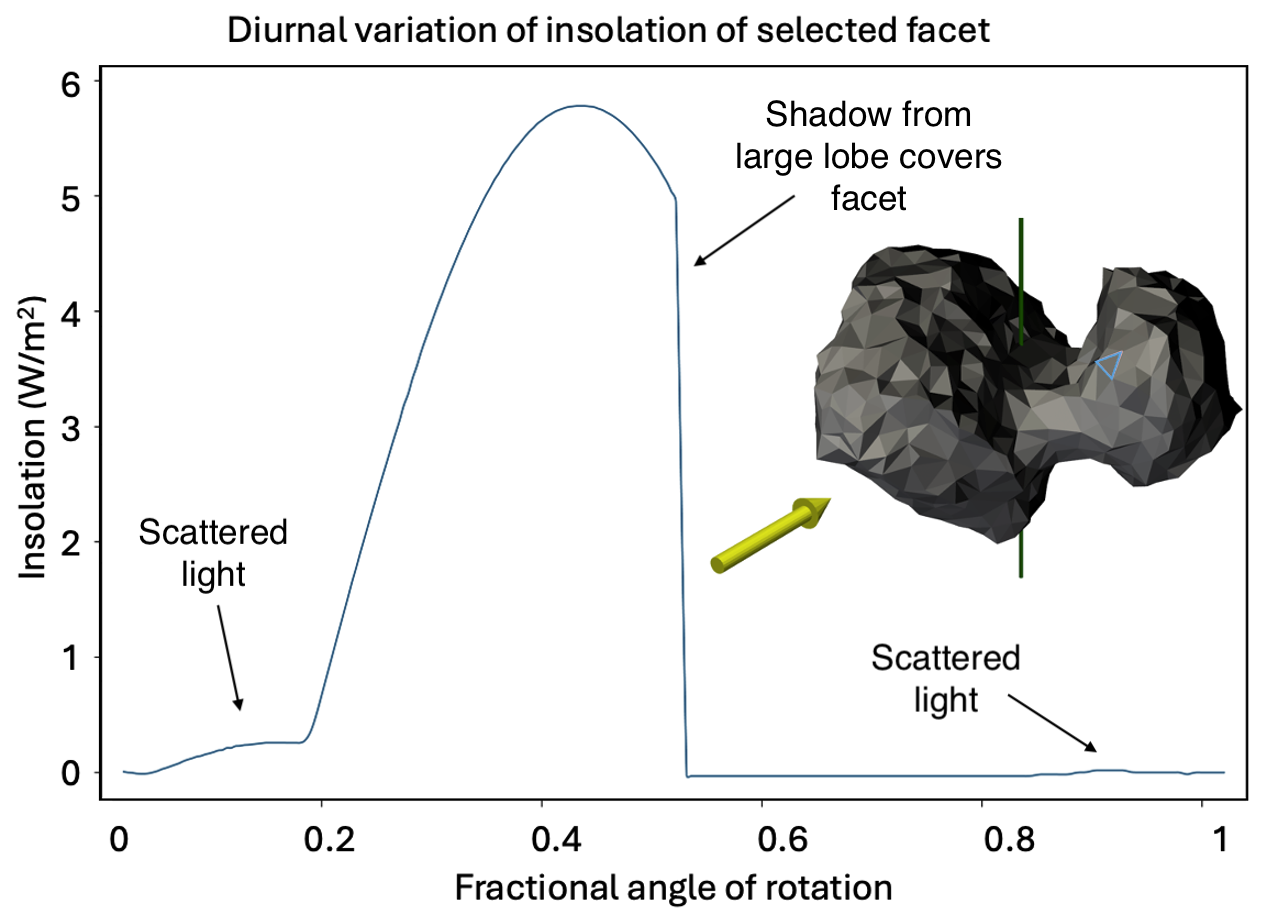

Figure 2: An example insolation curve from a 1666 facet model of the bilobate comet 67P. The effects of scattered light can be seen either side of the main peak, this is particularly important for permanently shadowed regions. The selected facet is shown with a blue outline; sunlight direction is shown with a yellow arrow.

Results: We validated TEMPEST by comparing temperature time series with Spencer’s 1D model thermprojrs [1] under idealised conditions, showing consistent results – see Figure 3. Applied to high-resolution shape models of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and 101955 Bennu, the model produces detailed temperature maps that reflect the significant influence of self-shadowing and local geometry, quantifying, for example, the temperature reduction in shadowed craters. Non-periodic simulations have been run to explore rotational transitions and eclipse effects, enabling new modes of comparison with observational datasets. The modular scattering and roughness components offer a powerful way to assess how sub-resolution scale parameters impact apparent thermal inertia and surface radiative behaviour. TEMPEST is already being used to interpret thermal data from recent missions, including Lucy, and can be adapted for upcoming datasets from targets like those of Comet Interceptor and Europa Clipper.

Figure 3: TEMPEST shows good agreement with ‘industry standard’ thermophysical models in 1 dimension.

TEMPEST is open-source and available at:

github.com/duncanLyster/TEMPEST/

Acknowledgement: This work was made possible by support from the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council.

References:

[1] Spencer, J.R., Lebofsky, L.A., and Sykes, M.V., 1989. Systematic biases in radiometric diameter determinations. Icarus, 78(2), pp.337-354.

[2] Lyster, D., Howett, C., & Penn, J. (2024). Predicting surface temperatures on airless bodies: An open-source Python tool. EPSC Abstracts, 18, EPSC2024-1121.

[3] Lyster, D.G., Howett, C.J.A., Spencer, J.R., Emery, J.P., Byron, B., et al. (2025). Thermal Modelling of the Flyby of Binary Main Belt Asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh by NASA’s Lucy Mission. Submitted to EPSC Abstracts, 2025.

How to cite: Lyster, D., Howett, C., and Penn, J.: TEMPEST: A Modular Thermophysical Model for Airless Bodies with Support for Surface Roughness and Non-Periodic Heating, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1479, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1479, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Context

Recently, several asteroids with super-fast rotation rates, ranging from just 10 seconds to a few minutes, have been observed to exhibit significant drift in their semi-major axes, potentially caused by the Yarkovsky effect. Standard analytical models of the Yarkovsky effect suggest that these objects must possess extremely low thermal inertia to produce such strong orbital drift under rapid rotations. However, such low thermal inertia implies specific structural characteristics, such as a fine regolith layer and/or a highly porous internal structure, both of which are challenging to sustain under the intense inertial stresses caused by their extreme rotational rates.

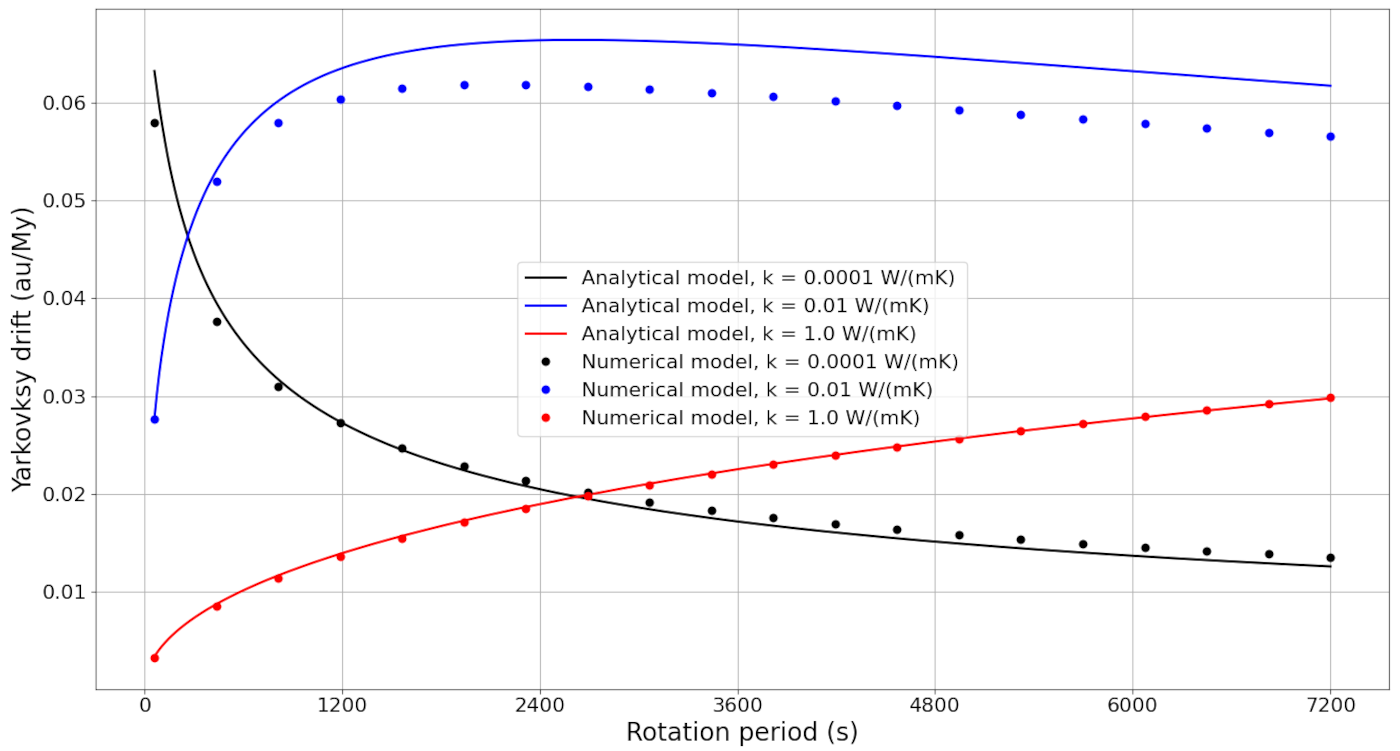

The strong Yarkovsky effect observed under extremely fast rotation can seem counterintuitive. Since existing analytical models of the Yarkovsky effect rely on various assumptions, their applicability to cases of extremely fast rotation, where some of these assumptions may no longer hold, becomes questionable. We aim to evaluate the validity of the analytical models in such scenarios and to determine whether the observed drift in the semi-major axis of rapidly rotating asteroids can be explained by the Yarkovsky effect.

Methods and Model Validation

To test the analytical model’s validity under fast spins, we developed an open-source numerical model of the Yarkovsky effect, tailored to address cases of super-fast rotation. Given that extremely low thermal inertia effectively forms an insulating surface layer, where thermal wave penetration depths can be on the order of microns, the model is designed to deliver high-resolution calculations in both depth and time. This allows for precise modeling of steep spatial and temporal temperature gradients on and beneath the asteroid's surface, which is essential for accurately computing the Yarkovsky drift in scenarios involving super-fast rotation.

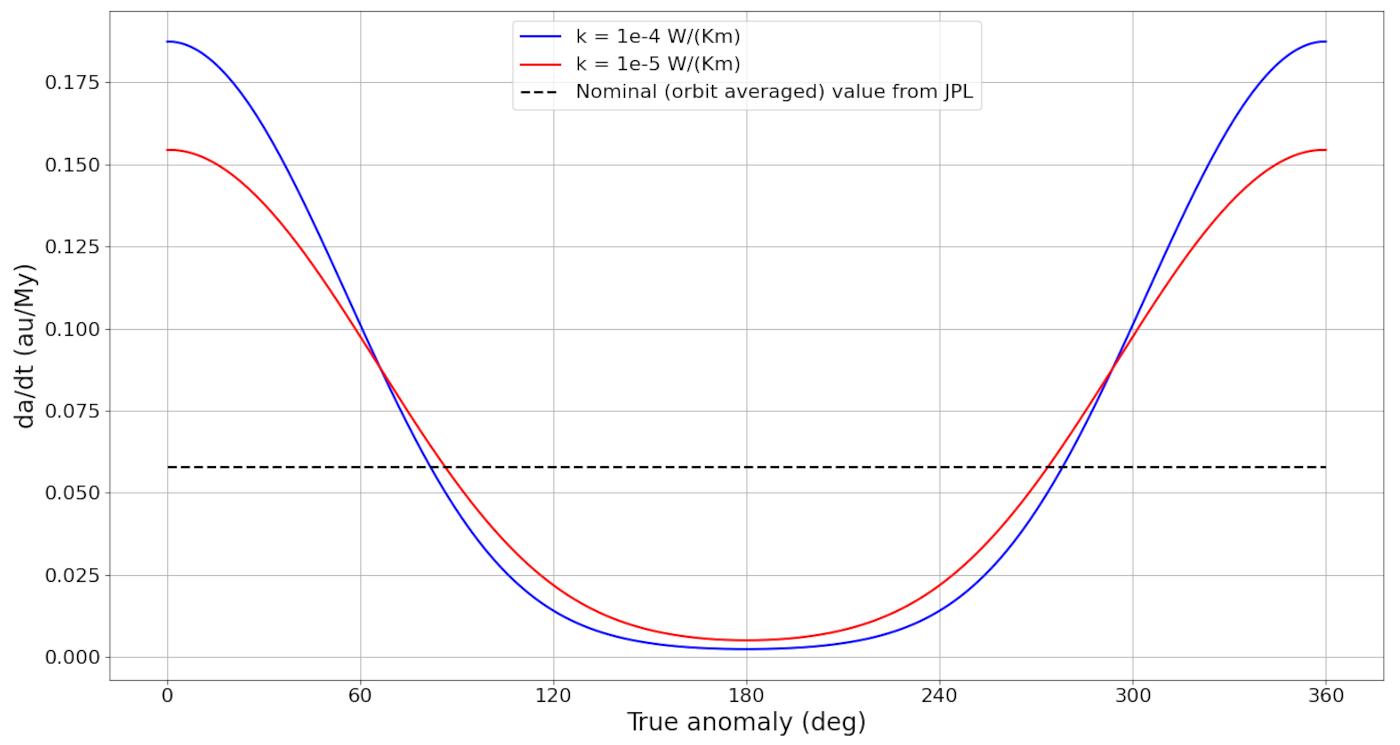

Figure 1 presents a comparison of the Yarkovsky drift computed using our numerical model and a standard analytical model for a fictitious asteroid on a circular orbit (R = 10 m, ρ = 1000 kg/m3, Cp = 1000 J/(kgK), a = 1 au), considering three values of thermal conductivity k and rotation periods ranging from 10 seconds to 2 hours. A comparison between our numerical model and the analytical model shows very good agreement, confirming that the observed semi-major axis drift can be attributed to extremely low thermal inertia.

Figure 1: Comparison of Yarkovsky drift computed using the numerical and standard analytical model (Vokrouhlický 1998, 1999)

Results

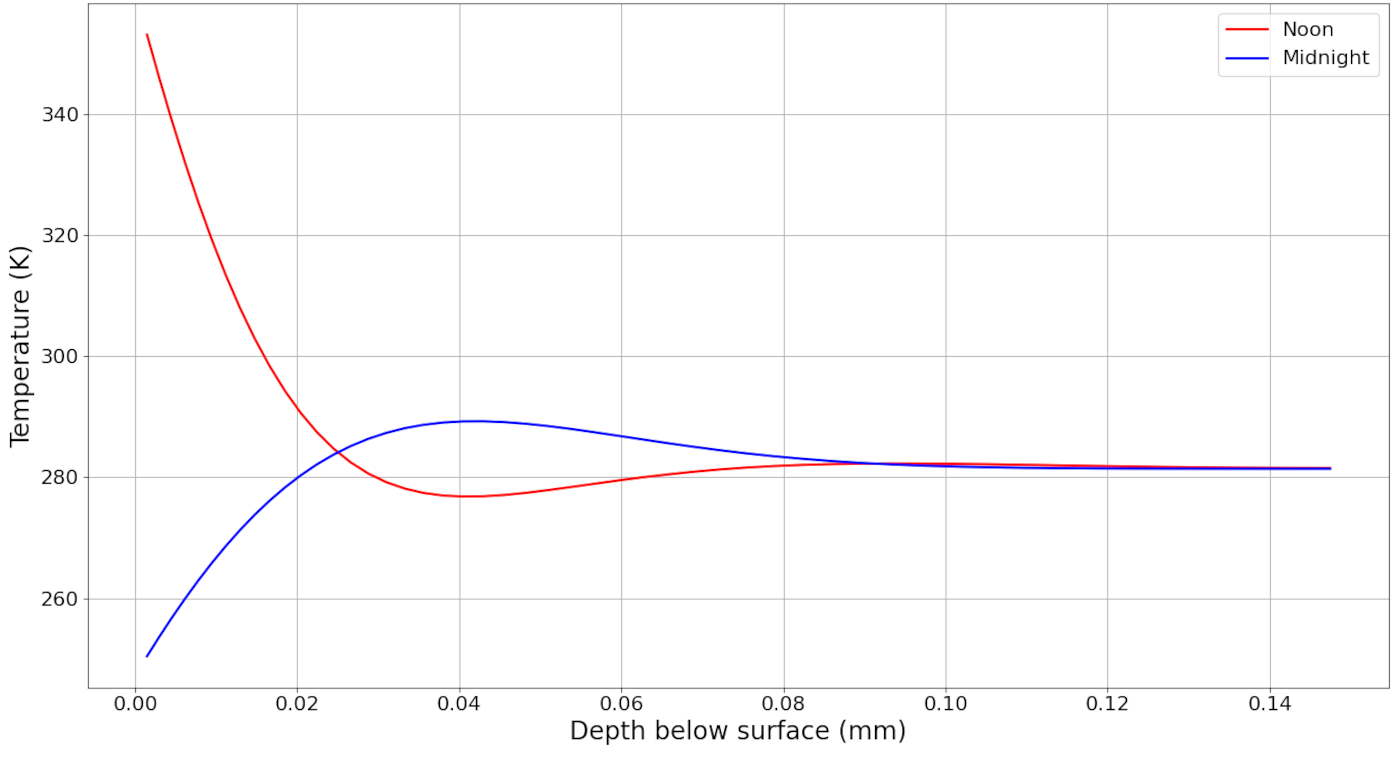

As an illustrative example, we present the thermal characteristics of the super-fast rotating near-Earth asteroid 2016 GE1, for which a rotation period of approximately 34 seconds has been measured.

The analysis assumes the following nominal parameters: a= 2.06 au, e = 0.52, D = 14 m, ρ = 2500 kg/m3, Cp = 1000 J/(kg K), and a spin axis orthogonal to the orbital plane. JPL reports a relatively large semi-major axis drift of da/dt = 0.058 au/My.

Figure 2 illustrates the resulting extreme temperature gradient with depth, showing variations of several tens of degrees within a fraction of a millimeter beneath the surface.

Figure 2: Temperature variation with depth beneath the surface of asteroid 2016 GE1

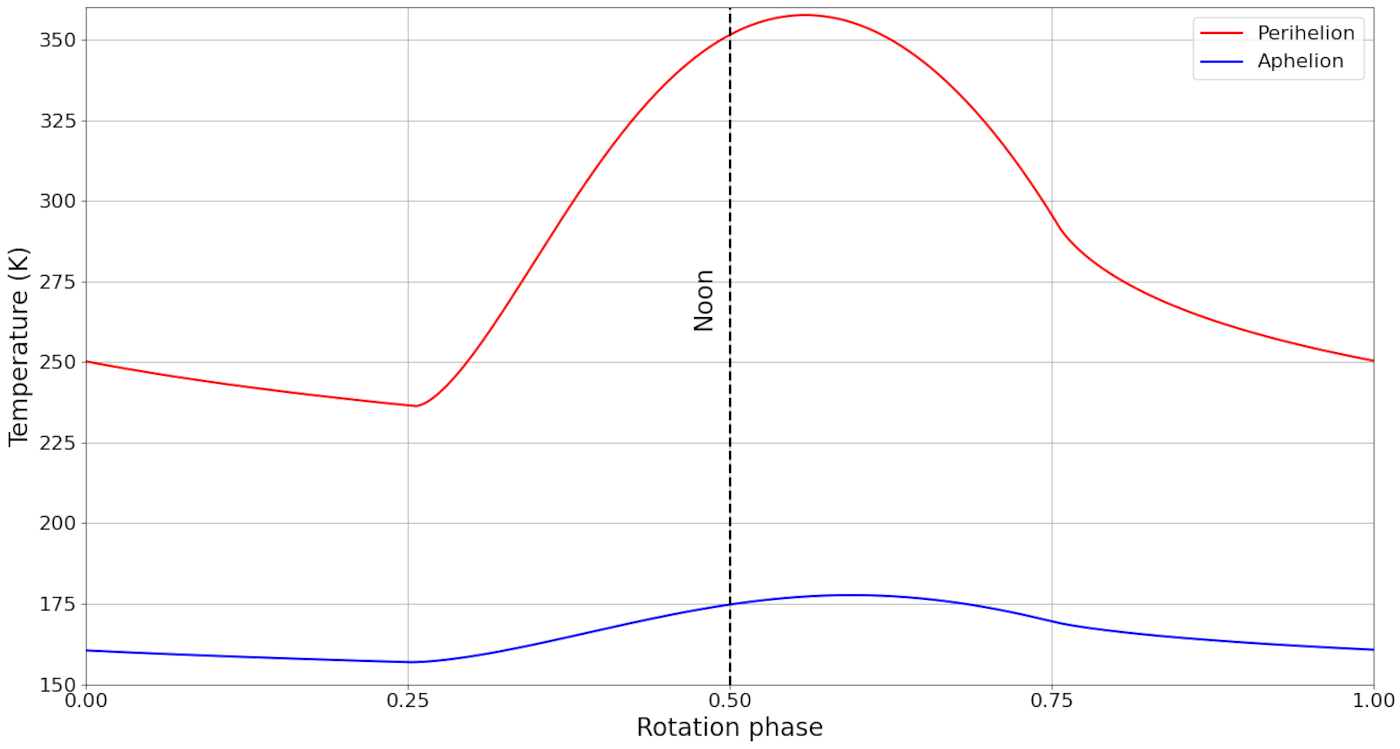

As a consequence of the steep subsurface temperature gradients, we observe a pronounced diurnal temperature variation, despite the extremely rapid rotation. Figure 3 shows the diurnal temperature cycle at the equator, both at perihelion and aphelion.

Figure 3: Diurnal temperature variation at the equator of 2016 GE1

A significant difference is evident between these two orbital positions, resulting in the Yarkovsky drift being predominantly generated near perihelion, as illustrated in Figure 4, which shows that the drift near perihelion is an order of magnitude greater than at aphelion. Given that low thermal conductivity plays a crucial role in the Yarkovsky drift of super-fast rotators, this highlights the importance of modeling the thermal properties of asteroids as a function of heliocentric distance in order to obtain realistic estimates of the drift.

Figure 4: Dependence of the Yarkovsky drift on orbital position for a highly eccentric orbit of 2016 GE1

The developed model demonstrates that a significant Yarkovsky drift can be sustained even in cases of extremely rapid rotations. This finding potentially implies that specific structural characteristics, such as a fine regolith layer and/or a highly porous internal structure, can persist despite the intense inertial stresses caused by extreme rotational rates.

References:

Vokrouhlický , D. 1998.Diurnal Yarkovsky effect as a source of mobility of meter-sized asteroidal fragments. I. Linear theory. Astronomy and Astrophysics 335, 1093–1100.

Vokrouhlický, D. 1999. A complete linear model for the Yarkovsky thermal force on spherical asteroid fragments. Astronomy and Astrophysics 344, 362–366.

Acknowledgements: This research was supported by The Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia through Project No. 7453 Demystifying enigmatic visitors of the near-Earth region (ENIGMA)

How to cite: Marceta, D., Novakovic, B., and Gavrilovic, M.: Numerical Modelling of the Yarkovsky Effect for Super-Fast Rotating Asteroids, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1040, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1040, 2025.

Introduction

Near-Earth asteroids and small main-belt asteroids (MBAs) with diameters between 200 m and 20 km are thought to be rubble piles. Most of their satellites are believed to be born from rotational mass shedding of the primary body, where the spin-up of a primary asteroid triggers mass shedding, creating a transient debris disk that finally re-accumulates to form satellite(s). In this scenario, a prolate satellite in a compact orbit is expected from theoretical predictions (Walsh et al, 2008). However, recent space missions have revealed a remarkable diversity of binary configurations. One striking anomaly is the (152830) Dinkinesh system, which hosts a contact-binary satellite named Selam in a wide orbit (Levison et al, 2025). In addition, several asteroids in this size range have been found to have more than one satellite. These findings reveal a diversity in the orbital architecture, satellite shape, and the number of satellite(s) when multiple asteroid systems are considered.

Existing models in the literature (Jacobson & Scheeres, 2011; Madeira et al, 2023) prefer to reconstruct this diversity through a single mass shedding event, but recent simulations (Agrusa et al, 2024) suggest that the actual picture of satellite formation is quite different, and the morphological properties of Selam have still not been convincingly reproduced. In this work, by considering multiple mass shedding and thus multi-generation of satellites, we propose a unified and self-consistent framework capable of covering all aspects of this configuration diversity.

Results

Through gravitational N-body simulations, we find that if multiple episodes of mass shedding and multi-generations of satellites are considered, the pre-existing satellite can strongly influence the subsequent satellite formation. Taking into account the orbital migration of the pre-existing satellite, this leads the system evolution after a subsequent mass shedding to different pathways, where the observed diversity in binary asteroid configurations can be naturally produced. Furthermore, a dynamical atlas of binary asteroid evolution is presented.

We suggest that the Selam-like contact binary satellite is more likely to originate from two separate mass shedding events and the subsequent inter-satellite collision, in which satellite migration also plays an important role. This also suggests a new formation mode for contact binary asteroids like Itokawa. We also find that ~ 44% of known binaries are located in the parameter ranges corresponding to multi-satellite histories, suggesting that the mechanisms shown in this work are prevalent in the evolution of binaries. Consequently, Selam-like satellites may be not rare, and satellites with even stranger shapes such as a contact triple, may also be found in the future.

This work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China grant No. 12372047.

References

Walsh, D. C. Richardson, P. Michel, Rotational breakup as the origin of small binary asteroids. Nature 454 (7201), 188–191 (2008).

Levison, et al., A contact binary satellite of the asteroid (152830) Dinkinesh. Nature 629 (8014), 1015–1020 (2024).

Jacobson, S. A. & Scheeres, D. J. Dynamics of Rotationally Fissioned Asteroids: Source of Observed Small Asteroid Systems. Icarus 214, 161–178 (2011).

Madeira, G., Charnoz, S. & Hyodo, R. Dynamical Origin of Dimorphos from Fast Spinning Didymos. Icarus 394, 115428 (2023).

Agrusa, H. F. et al. Direct N-body Simulations of Satellite Formation around Small Asteroids: Insights from DART’s Encounter with the Didymos System. The Planetary Science Journal 5, 54 (2024).