- 1University of Freiburg, Institute of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Geology, Freiburg, Germany (thomas.kenkmann@geologie.uni-freiburg.de)

- 2Independent Consultant, 80904 Colorado Springs, Colorado, USA

- 3Independent Consultant, 82609 Casper, Wyoming, USA

- 4School of Science, Casper College, 82601 Casper, Wyoming, USA

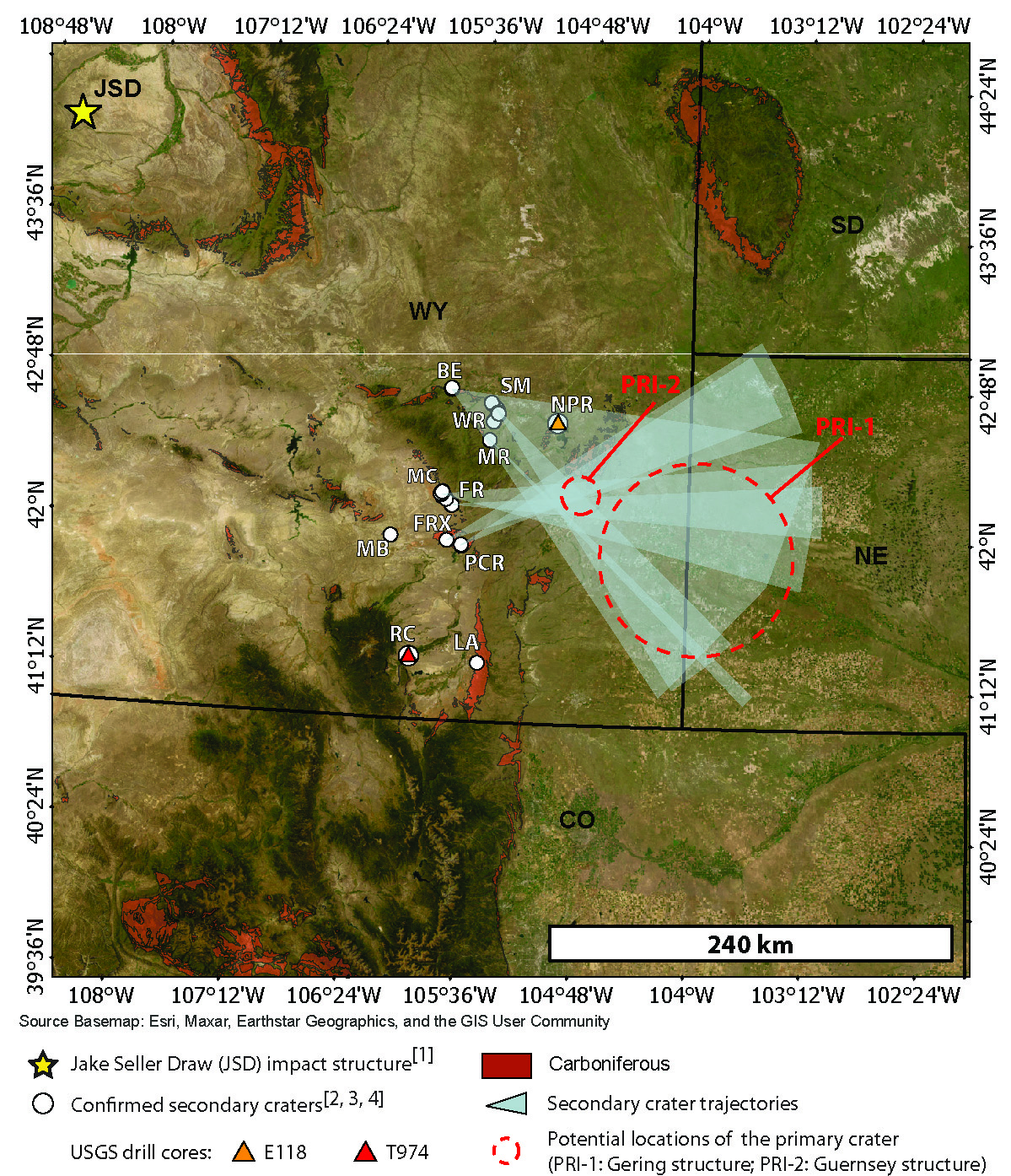

Secondary cratering is a widely recognized phenomenon on Moon, Mars, Mercury, and the icy satellites of Jupiter and Saturn. It was disputed if secondary craters exist on Earth in the presence of a 1-bar atmosphere until the first secondary crater field was discovered in 2022 in Wyoming, USA [1]. Here, we present and confirm fifteen additional secondary impact structures within the Wyoming crater field, USA, leading to the total number to 46 impact structures confirmed by shock effects. In addition, we identified more than 200 potential secondaries based on morphology. This expansion includes three newly identified crater areas. The minimum extent of the crater field measures actually 160 × 100 km (Fig. 1). All newly confirmed structures are stratiform and have a Permo-Pennsylvanian age of ~280 Myr. Although the degree of the preservation varies among the discovered craters, similarities between Wyoming’s secondary craters and those on the Moon and Mars are striking and include irregular and elongated crater shapes, shallow depth-to-diameter ratios, and clustered distributions and crater rays. A lack of iron meteorite fragments and trace geochemical impactor signatures is also characteristic for the secondary crater field.

On Earth, the identification of secondary craters is challenging due to active surface processes such as erosion, sedimentation and tectonic activity. The life-time of small craters is very limited [2]. The 280 Myr-old secondary crater field could only be preserved until today because it was buried immediately after its formation in a low-energy coastal environment and got re-exposed by tectonic uplift of the Rocky Mountains Front range system in the Cenozoic after a long period of burial. The completely consolidated state of strata helped to preserve the field until today. In fact, the craters today form erosion-resistant competent patches, which often form small hills; in other words, some can be considered as pedestal craters. There are several reasons for this: impact induced shock lithification [3] and post-impact quartzitic sealing of the numerous impact-induced rock fractures. The latter process appears to be dominant.

Fig. 1 The Wyoming crater field with trajectory corridors and the location of the potential primary crater.

With the additional secondary craters, we could construct new trajectory corridors to refine the location of the primary crater (Fig. 1). Using trajectory reconstruction and pre-processed geophysical datasets, we now have identified two potential sites for the primary crater (1) PRI-1, provisionally named Gering structure, centered around 41°55‘N / 104°00’W with an estimated diameter of 80-120 km, and (2) PRI-2, provisionally named Guernsey structure, centered at 42°12’N / 104°50’W with a smaller diameter of 20-40 km. The possible crater location PRI-2 is much smaller and closer to the discovered crater field than PRI-1. Our calculations of ballistic ejecta trajectories including impact velocities, impact energies, block sizes, and the simulations of the crater forming process that are based on these ballistic input parameters [1] are valid for the primary crater location PRI-1, but need refinement for PRI-2. For the latter location PRI-2, the ejection distances are likely too short, and the impact velocities appear insufficient to generate significant shock volumes during the secondary cratering events. In such a scenario, the majority of shocked minerals discovered in many of the secondary craters may likely have originated from the primary crater itself.

References

[1] Kenkmann, T., Müller, L., Fraser, A., Cook, D., Sundell, K., and Rae, A.S.P., 2022, Secondary cratering on Earth; the Wyoming impact crater field: GSA Bulletin, vol. 134 (9-10), 2469-2484, https://doi.org/10.1130/B36196.1.

[2] Hergarten, S. and Kenkmann, T., 2015. The number of impact craters on Earth: Any room for further discoveries? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 425, 187-192. doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2015.06.009.

[3] Kenkmann, T., Sundell, K.A., and Cook, D., 2018, Evidence for a large Paleozoic Impact Crater Strewn Field in the Rocky Mountains: Scientific Reports, vol. 8, 13246. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31655-4.

How to cite: Kenkmann, T., Sturm, S., Wieck, I., Cook, D., Fraser, A., and Sundell, K.: More impact structures in Wyoming´s secondary crater field , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1664, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1664, 2025.