- 1University of Belgrade, Faculty of Mathematics, Department of Astronomy, Belgrade, Serbia

- 2Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (IAA-CSIC), Granada, Spain

Introduction

The spin period is essential for asteroid studies: it underpins the determination of surface thermal properties (Delbo et al., 2015; Hung et al., 2022; Novaković et al., 2024), internal structures (Rozitis et al., 2014; Fodde & Ferrari), and modeling non-gravitational effects (Yarkovsky, YORP; Vokrouhlický et al., 2015; Fenucci & Novaković, 2022). All these are also highly relevant for planetary defense-related studies.

Rotation periods have been derived from light curves built from photometric observations and fall into dense (high-cadence) or sparse (survey) regimes. Dense photometry—targeted runs over 2–3 nights—yields reliable periods but is limited by telescope-time demands. For these reasons, until recently, the number of asteroids with determined rotation periods was limited. However, reducing sparse photometry data requires additional steps (e.g., corrections for changes in observational geometry). Generally, it makes the rotation period extraction more challenging and less reliable.

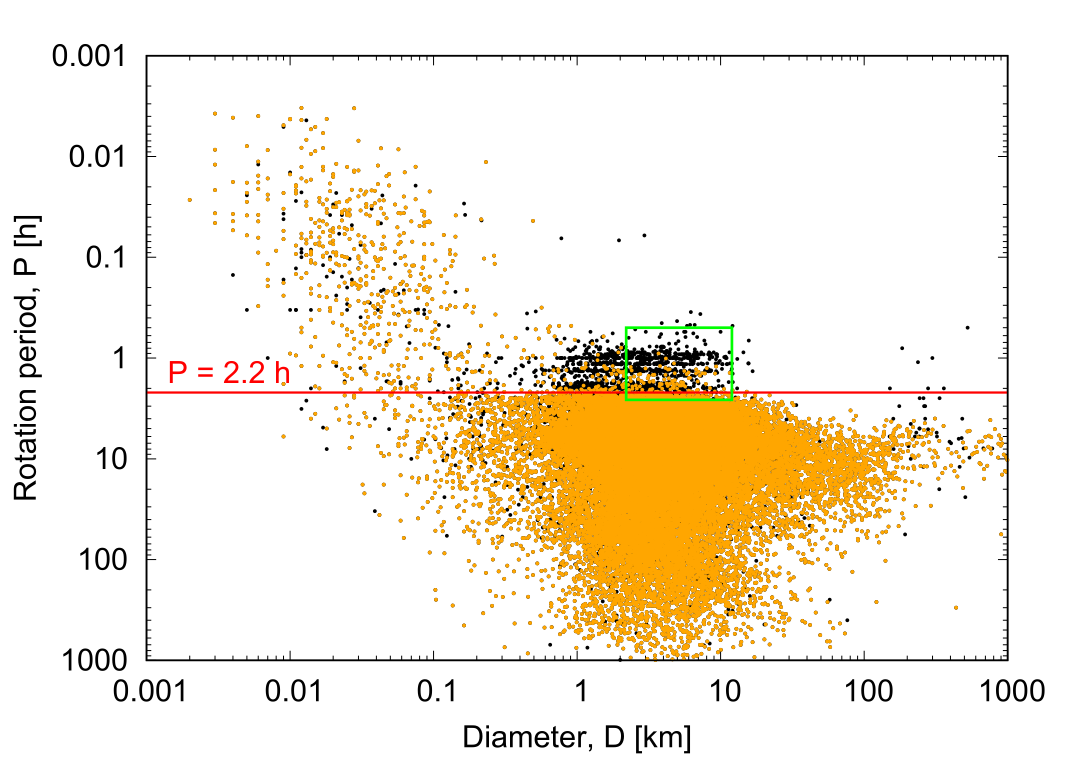

The so-called super-fast rotators (SFRs) are objects rotating faster than the cohesionless “spin barrier” at 2.2 hr (Pravec & Harris, 2000). They are especially interesting to study, but are even more prone to misidentification in sparse data (Warner & Harris, 2011). To enhance our understanding of SFRs, it is essential to reliably obtain their periods using dense photometry. In this respect, the SFR candidates identified from sparse data are good starting points. For this reason, we initiated a long-term monitoring program of SFRs candidates. The first part of our campaign targeted 15 SFRs candidates to verify their rotation periods via high-precision dense photometry.

Targets and Equipment

The targets are selected according to the results obtained by Waszczak et al. (2015), Erasmus et al. (2018, 2019), Pal et al. (2020), and Chang et al. (2014, 2022). All these are SFR candidates identified based on the sparse photometry data. Figure 1 shows the spin period of asteroids as a function of the diameter, taken from the Asteroid Lightcurve Database (LCDB; Warner et al., 2009). Our targets are possibly located approximately inside the box.

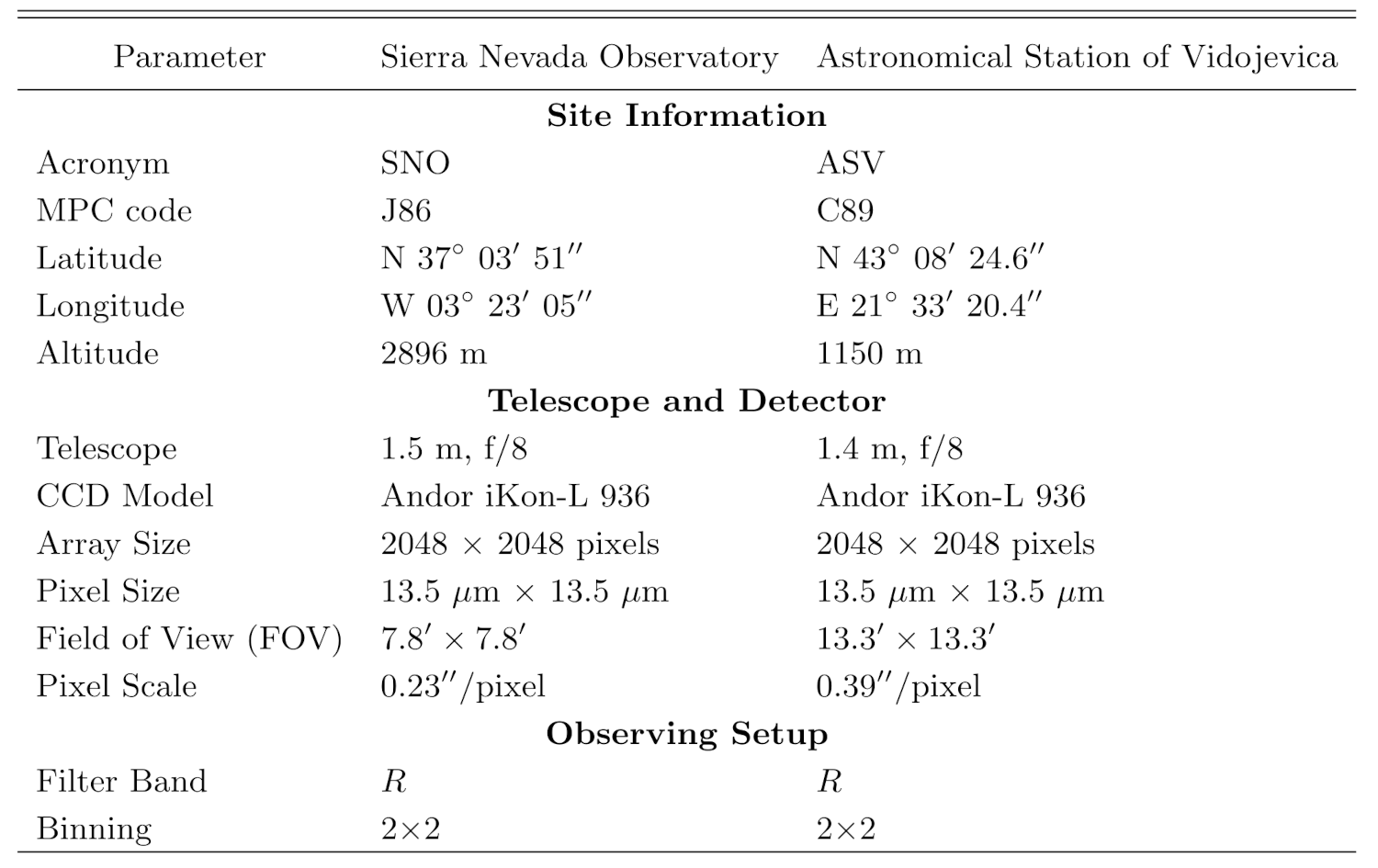

The observations were performed from Observatorio de Sierra Nevada (OSN) and the Astronomical Station of Vidojevica (ASV). Table 1 provides additional information about the equipment.

Methods

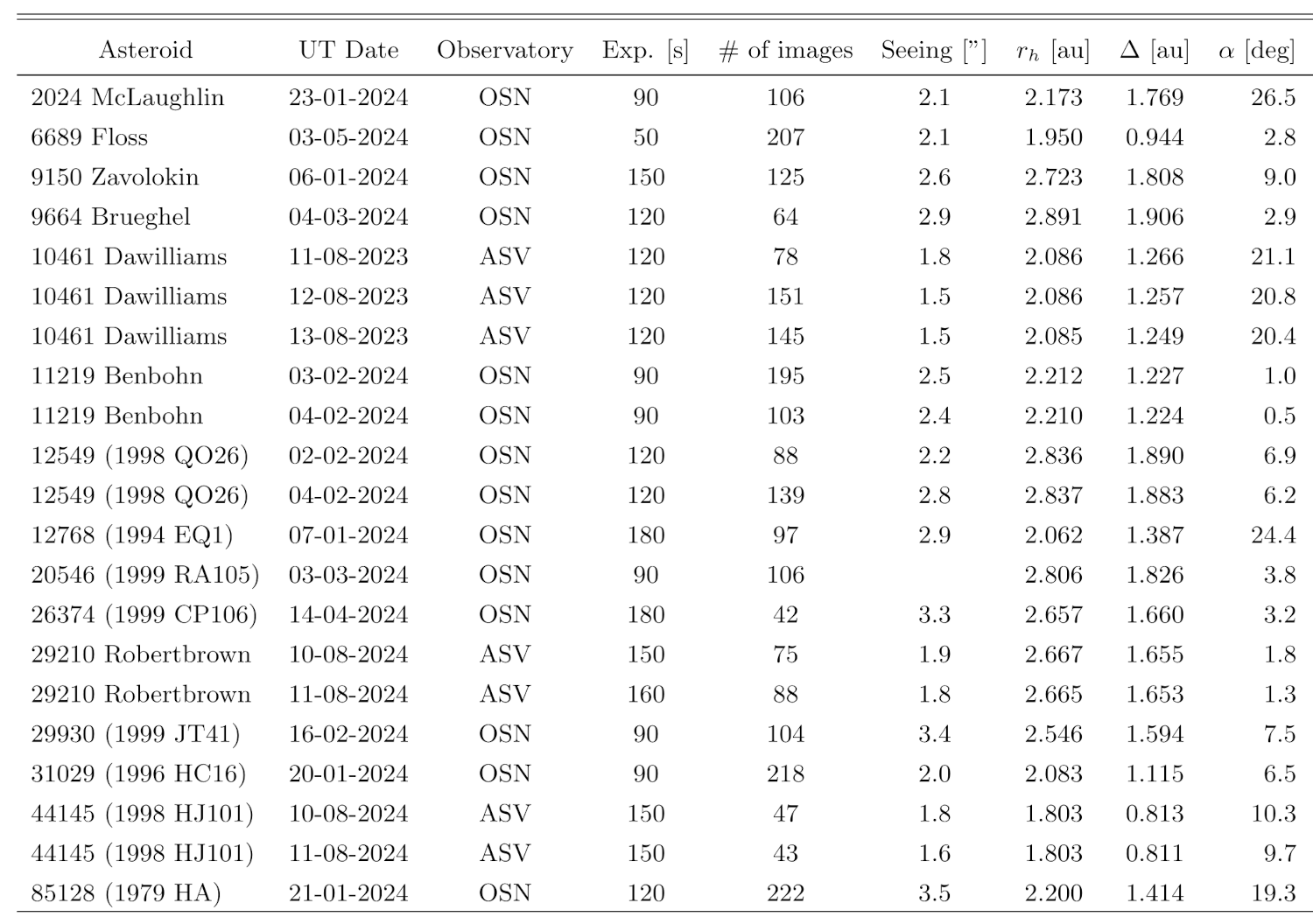

The image processing, measurement, and period analysis were done using procedures incorporated into the Tycho Tracker software (Parrott, 2020). All raw images underwent bias and flat-field corrections (ASV images were also dark-corrected). Aperture photometry was calibrated against the ATLAS All-Sky Stellar Catalog (Tonry et al., 2018). We fitted the 2nd–6th order Fourier series to determine double-peaked periods and amplitudes; uncertainties came from Monte Carlo resampling. Observing circumstances are in Table 2.

Resuts

Rotation periods were secured for 12 of the 15 targets. Only four literature values were confirmed; three of these—(2024) McLaughlin, (31029) 1996 HC16 (shown in Fig. 2), and (44145) 1998 HJ101—remain bona fide SFRs. We measured longer periods for the other eight asteroids, excluding them as SFRs. This underscores the need for dense photometry follow-up to validate SFR candidates.

Acknowledgments

BN acknowledges support by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia, GRANT No 7453, Demystifying enigmatic visitors of the near-Earth region (ENIGMA). Observations were made at the Observatorio de Sierra Nevada, operated by the Instituto de Astrofı́sica de Andalucı́a, and Astronomical Station of Vidojevica, operated by the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade.

References

Chang, C.-K. and 12 colleagues 2014. 313 New Asteroid Rotation Periods from Palomar Transient Factory Observations.

ApJ, 788. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/788/1/17

Chang, C.-K. and 14 colleagues 2022. The Large Superfast Rotators Discovered by the Zwicky Transient Facility. ApJ, 932. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac6e5e

Delbo, M., Mueller, M., Emery, J.P., Rozitis, B., & Capria, M.T. 2015, Asteroid Thermophysical Modeling, 107–128, Asteroids IV, (University of Arizona Press)

Erasmus, N., McNeill, A., Mommert, M., Trilling, D.E., Sickafoose, A.A., van Gend, C. 2018. Taxonomy and Light-curve Data of 1000 Serendipitously Observed Main-belt Asteroids. ApJSS, 237. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/aac38f

Erasmus, N., McNeill, A., Mommert, M., Trilling, D.~E., Sickafoose, A.~A., Paterson, K. 2019. A Taxonomic Study of Asteroid Families from KMTNET-SAAO Multiband Photometry. ApJSS, 242. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ab1344

Fenucci, M., Novakovic, B. 2022. MERCURY and ORBFIT Packages for Numerical Integration of Planetary Systems: Implementation of the Yarkovsky and YORP Effects. SerAJ, 204, 51–63. doi:10.2298/SAJ2204051F

Fodde, I., Ferrari, F. 2025. Dynamical modelling of rubble pile asteroids using data-driven techniques. A&A 695. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202452432

Hung, D., Hanus, J., Masiero, J.~R., Tholen, D.J. 2022. Thermal Properties of 1847 WISE-observed Asteroids. PSJ, 3. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac4d1f

Novakovic, B., Fenucci, M., Marceta, D., Pavela, D. 2024. ASTERIA-Asteroid Thermal Inertia Analyzer. PSJ, 5. doi:10.3847/PSJ/ad08c0

Pal, A. and 12 colleagues, 2020. Solar System Objects Observed with TESS--First Data Release: Bright Main-belt and Trojan Asteroids from the Southern Survey. ApJSS, 247. doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ab64f0

Parrott, D. 2020, Tycho Tracker: A New Tool to Facilitate the Discovery and Recovery of Asteroids using Synthetic Tracking and Modern GPU Hardware. JAVSO, 48, 262.

Polishook, D. 2013, Minor Planet Bulletin, 40, 42

Pravec, P., Harris, A.W. 2000. Fast and Slow Rotation of Asteroids. Icarus 148, 12–20. doi:10.1006/icar.2000.6482

Rozitis, B., Maclennan, E., Emery, J.P. 2014. Cohesive forces prevent the rotational breakup of rubble-pile asteroid (29075) 1950 DA. Nature 512, 174–176. doi:10.1038/nature13632

Tonry, J.L. and 8 colleagues 2018. The ATLAS All-Sky Stellar Reference Catalog. ApJ, 867. doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aae386

Vokrouhlicky, D., Bottke, W.F., Chesley, S.R., Scheeres, D.J., & Statler, T.S. 2015, The Yarkovsky and YORP Effects, 509–531, Asteroids IV, (University of Arizona Press)

Warner, B.D., Harris, A.W., Pravec, P. 2009. The asteroid lightcurve database. Icarus 202, 134–146. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2009.02.003

Warner, B.D., Harris, A.W. 2011. Using sparse photometric data sets for asteroid lightcurve studies. Icarus 216, 610–624. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.10.007

How to cite: Novakovic, B. and Gutiérrez, P.: Monitoring super-fast rotating asteroid candidates, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1666, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1666, 2025.