Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

MITM8

Session assets

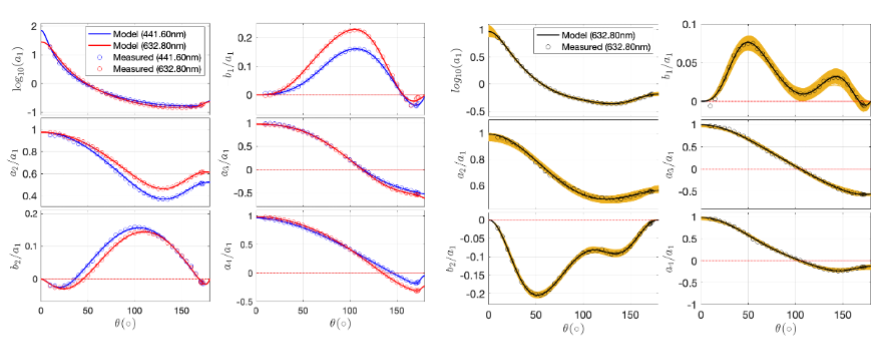

[1] Hapke B. (1993) Theory of Reflectance and Emittance Spectroscopy.

[2] Raponi A. et al., (2020) 14th EPSC 2020, abstract 761.

[3] De Sanctis M. C. (2002) SSR, 163, 329-369.

How to cite: Raponi, A., Ciarniello, M., Formisano, M., Filacchione, G., Capaccioni, F., De Sanctis, M. C., and Frigeri, A.: Roughness of planetary surfaces: statistical multi-facet approach combining Hapke and fractal theories, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1932, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1932, 2025.

The growing availability of hyperspectral data from planetary missions ranging from CubeSats to flagship programs has led to many studies aiming to infer surface mineralogy through remote sensing techniques. The Moon Mineralogical Mapper (M³) aboard Chandrayaan-1 provides visible and near-infrared data (430–3000nm) at 140 m/pixel resolution and has been widely used to infer lunar surface composition [1]. A common strategy involves applying unmixing models, often Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NNMF), to M³ images with varying reflectance and compositional properties, using laboratory reference spectra from the RELAB database for comparison [2,3]. These spectra from standard materials represent typical lunar minerals such as olivine, pyroxenes, plagioclase, iron-titanium oxides, and volcanic glasses.

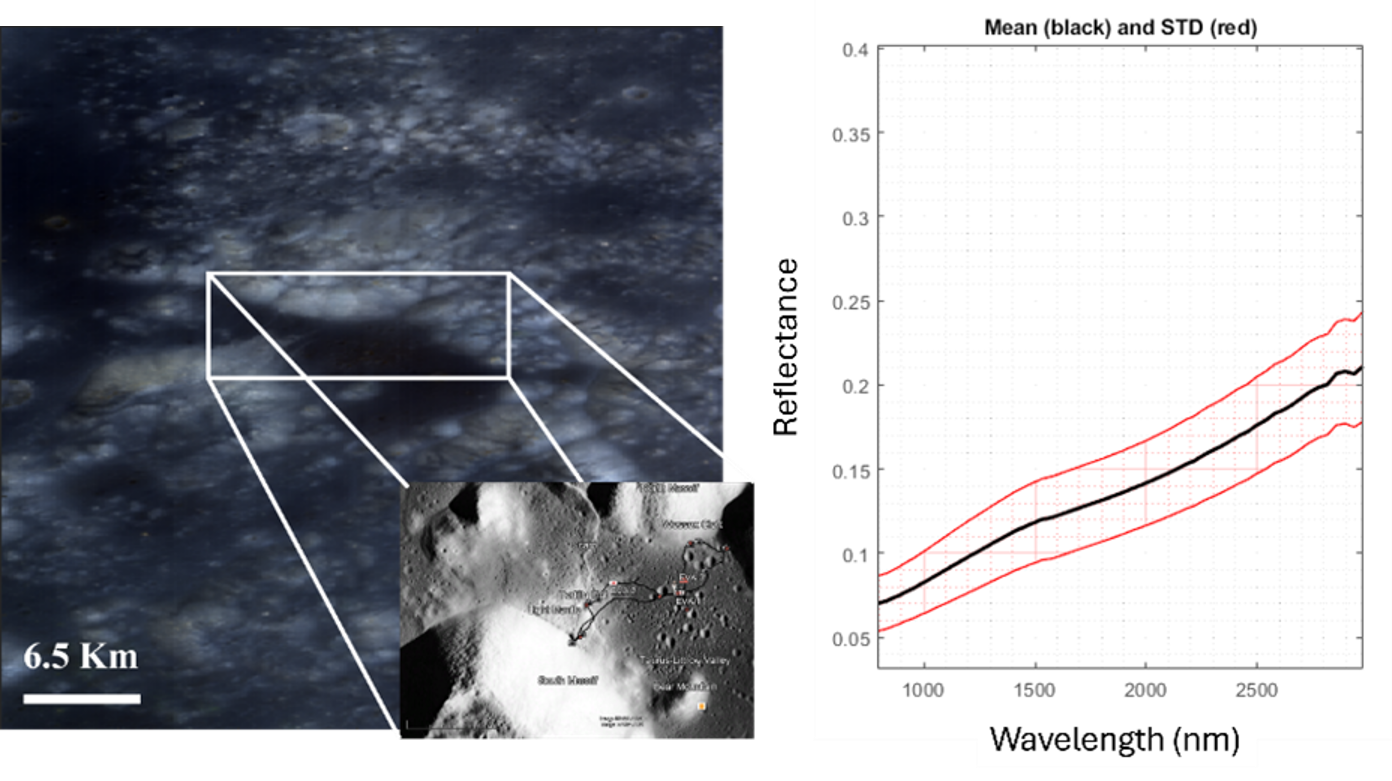

This study first focuses on reproducing previous efforts to estimate the lunar mineralogy, applied to the Apollo 17 landing site (Figure 1). Then it shifts toward highlighting the methodological uncertainties involved in interpreting hyperspectral imagery using unmixing models in remote sensing applications.

Figure. 1 (Top)Taurus-Littrow Valley. (Bottom) Mean (dark) reflectance spectrum and standard deviation (red) of the Taurus-Littrow Valley hyperspectral image.

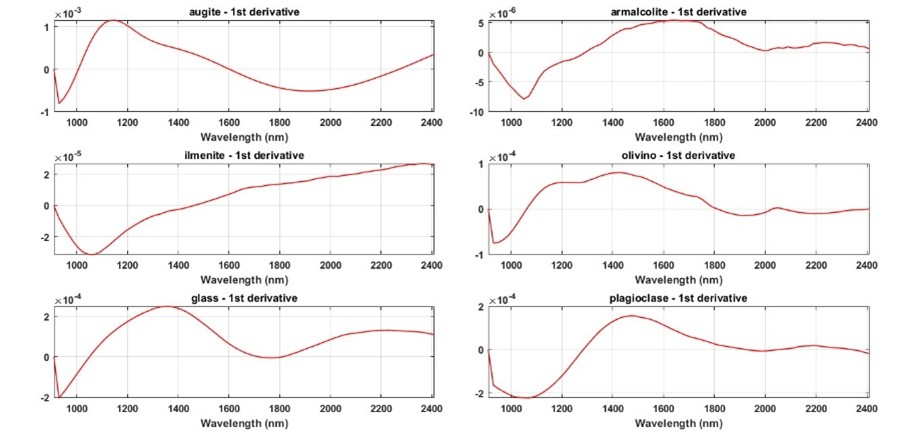

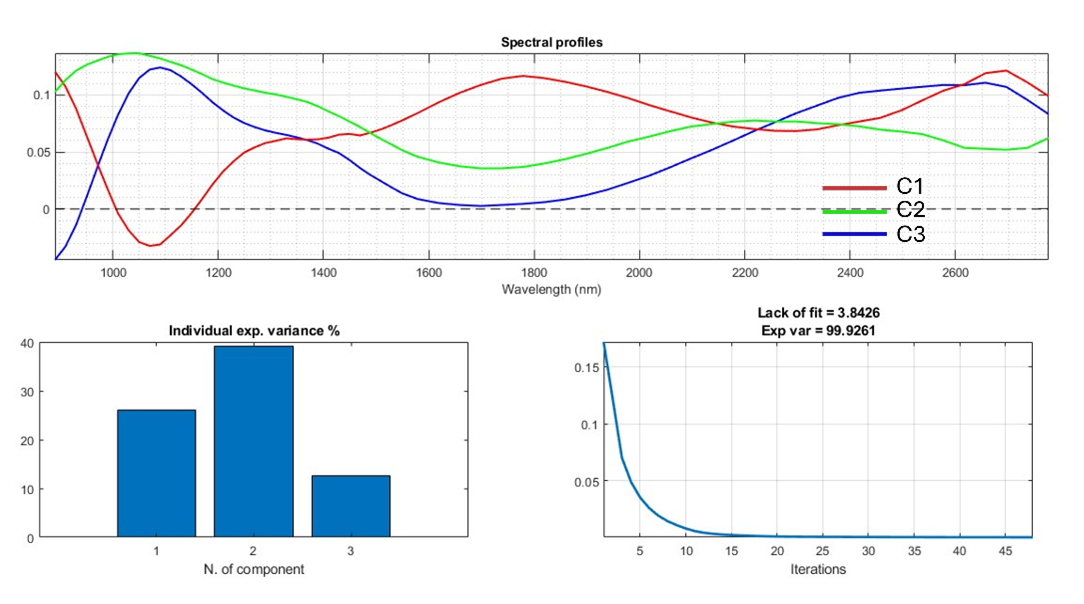

In the initial stage, a spatial binning with 8X8 window was applied to reduce the signal-to-noise ratio of the image. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was then used to reduce data dimensionality and highlight surface variations. Initially applied on the binned image, PCA revealed that the first component explained 98% of the variance, mainly reflecting topography and illumination differences. To minimize these effects and enhance chemical information, the first derivative of the spectral data was applied (same preprocessing was applied to reference spectra, Figure.2). A second PCA was then performed to determine the chemical rank of the matrix, which suggested that NNMF should be carried out with 3–4 principal components.

Figure. 2 First derivative of reference spectra from RELAB.

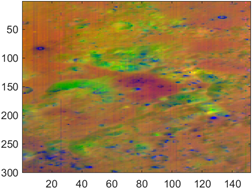

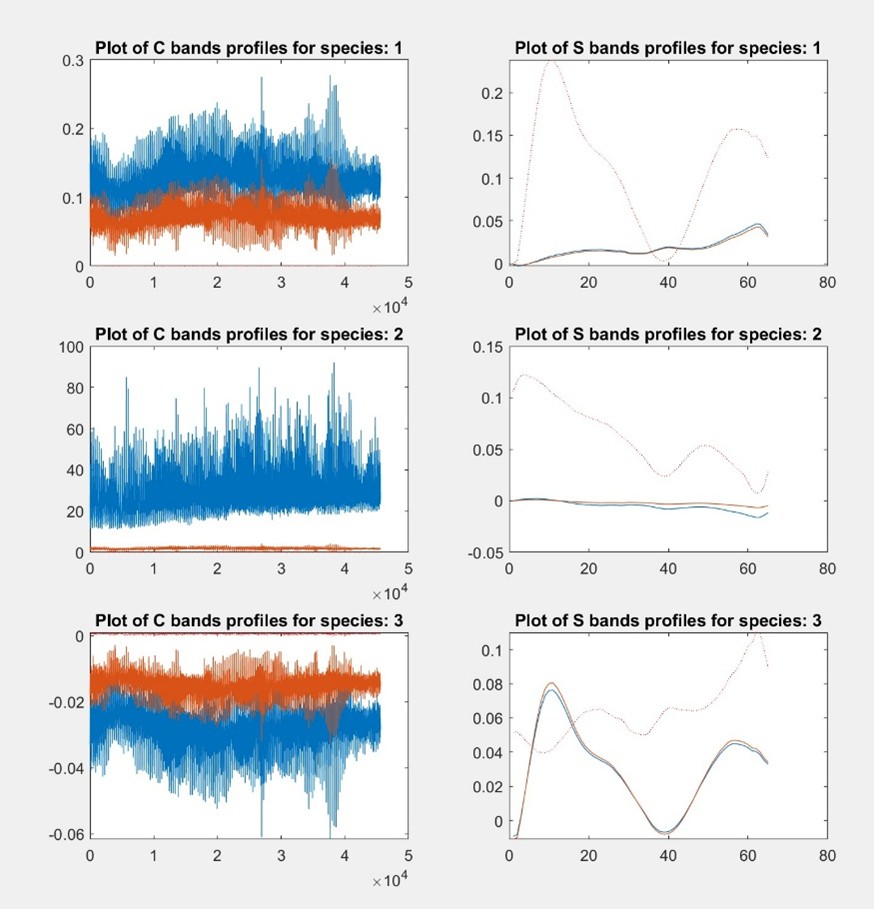

NNMF was performed to unmix and extract surface components, possibly revealing features that may correspond to geochemical variations. In this final stage, it was assumed that three principal components could be present within the image. Figure. 3 shows the spatial distribution of the combination of these three components (top), along with the corresponding “pure” spectra (bottom) extracted by the model after applying NNMF using endmember initialization and non-negativity constraints [4] applied to the contributions. Commonly, when these results were compared with preprocessed spectra from RELAB, compounds such as pyroxenes, olivine, volcanic-glass, may be identified (Figure. 3), with acceptable lack of fit and a total variance explanation exceeding 99%.

Figure. 3 False RGB showing the concentrations of the three main components after applying NNMF model using endmember initialization and non-negativity constraints.

However, while spectral unmixing models have been widely applied in remote sensing for decades, limited attention has been paid to the intrinsic ambiguities they involve. Although simpler ambiguities (such as those related to scale or sign) can often be addressed using basic constraints like non-negativity, rotational ambiguity remains a significant and underexplored source of uncertainty. For these reasons, it is important to highlight that solutions derived from NNMF (commonly referred to as Multivariate Curve Resolution with non-negativity constraints) depend considerably on the degrees of freedom allowed by the optimization algorithm (e.g., Alternating Least Squares, ALS). To visualize and quantify this issue, feasibility plots were employed through MCRbands and FACpack (Figure. 4), which map the set of all admissible solutions within the NNMF framework [5-7].

Figure. 4 Feasibility plots for the three components calculated. Right, the contributions and left, the spectral profiles obtained. Contributions: Blue and red represents the solution obtained and the plausible solution that could also be considered as optimal.

Figure 4 shows that any space covered between those solutions could be considered feasible. On the left, the spectra calculated and the feasible spectra both indicate a strong lack of specificity and uniqueness in the solutions, clearly stating that the model is not stable enough to be deemed an optimal solution. The extent of solution variability reveals that differences between the acceptable solution and real solutions for the considered species are considerable due to rotational freedom. In conclusion, we emphasize the importance of a more rigorous consideration of ambiguity in remote sensing applications. Additionally, the presence of regolith and volcanic rocks on the lunar surface makes it unlikely that a 140 m/pixel represents a pure mineral spectrum [8].

Keywords: Remote sensing, Chemometrics, Unmixing models, Near Infrared.

Acknowledgements: Work supported through the PAMMAT project: “Alteration processes in Mars and Moon Meteorites, and Terrestrial Analogues at different environments: Mars2020, Rosalind Franklin and Returned Samples from Mars and Moon” (Grant No. PID2022-142750OB-I00), funded by the Spanish Agency for Research (through the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, MCIN, and the European Regional Development Fund, FEDER).

References:

[1] R. O. Green, C. Pieters, P. Mouroulis,et al. (2011). Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 116 (E10) (E00G19).

[2] Adams, J. B., & McCord, T. B.(1971). Optical properties of mineral separates, glass, and anorthositic fragments from Apollo mare samples. In Proceedings of the Lunar Science Conference, vol. 2, p. 2183.

[3] Reflectance Experiment Laboratory (RELAB), 2008. Brown University, Providence

[4] De Juan, A., & Tauler, R.(2006). Multivariate curve resolution (MCR) from 2000: progress in concepts and applications. Critical reviews in analytical chemistry, 36(3-4), 163-176.

[5] Jaumot, J., & Tauler, R.(2010). MCR-BANDS: A user friendly MATLAB program for the evaluation of rotation ambiguities in Multivariate Curve Resolution. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 103(2), 96-107.

[6] Jaumot, J., Gargallo, R., De Juan, A., & Tauler, R.(2005). A graphical user-friendly interface for MCR-ALS: a new tool for multivariate curve resolution in MATLAB. Chemometrics and intelligent laboratory systems, 76(1), 101-110.

[7] Sawall, M., Kubis, C., Selent, D., Börner, A., & Neymeyr, K.(2013). A fast polygon inflation algorithm to compute the area of feasible solutions for three‐component systems. I: concepts and applications. Journal of Chemometrics, 27(5), 106-116.

[8] Cavalli, R. M. (2023). Spatial validation of spectral unmixing results: A systematic review. Remote Sensing, 15(11), 2822.

How to cite: Alberquilla, F., Gorla, G., Amigo, J. M., Aramendia, J., Martínez Arkarazo, I., Vazquez de la Fuente, I., Población, I., Coloma, L., Arana, G., Castro, K., and Madariaga, J. M.: Understanding the boundaries of “Spectral Unmixing”: Considerations for reliable mineralogical interpretation in remote sensing and space missions., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-705, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-705, 2025.

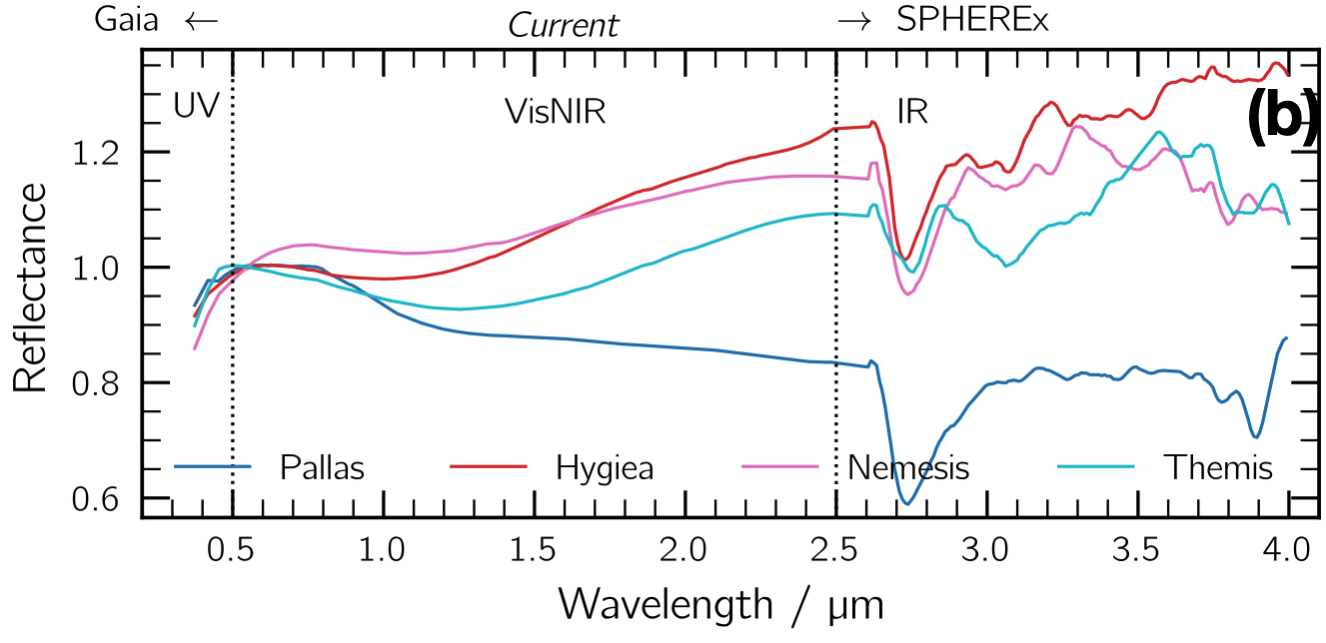

The near-Earth asteroid (3200) Phaethon displays activity when it passes its perihelion at 0.14 au from the Sun. It is also thought to be linked to the Geminid meteor shower (e.g. [1], [2]). Phaethon has been hypothesized to be connected to, for example, the main-belt asteroid (2) Pallas. The two asteroids could be remnants of a common parent body or Phaethon could be an ejected piece of Pallas. Thermal models of Phaethon show heterogeneity between its northern and southern hemispheres either in the surface grain size or porosity, or both [3]. Recently, Yamato-type (CY) carbonaceous chondrite meteorites have been connected to Phaethon and the CY meteorites are now believed to be originated from the asteroid [4]. Using CY meteorites, a light-scattering model is created for the surface of Phaethon to study its surface properties and heterogeneity.

Samples of 6 different CY meteorites are studied at the University of Helsinki Astrophysical Scattering Laboratory. The ground samples reflectance spectra is measured using an integrating sphere spectrometer and linear polarization using a polarizing goniometer. The mineralogy of the samples has been studied with XRD by King et al. [5]. The samples contain mostly olivine and iron sulphide, and small amounts of pyroxene and metals. The iron sulphide is in the form of troilite. For modeling, the samples are simplified as olivine particles with troilite inclusions. A multiparticle media is then constructed of these particles. Light-scattering simulations with SIRIS (geometric optics with diffuse scatterers framework) [6], RT-CB (radiative transfer and coherent backscattering code) [7], and exact calculations based on the Maxwell Equations are combined to recreate the measured spectral and polarization properties for the samples. A simulation model of the meteorite sample should be able to replicate both the spectral and polarization measurements, and the simulation parameters are tuned until these requirements are met.

Simulating the multiparticle media follows a method described in Martikainen et al. [8]. First the light-scattering properties of troilite inclusions are obtained by simulating troilite as different sized single particles using SIRIS and exact calculations. The light-scattering properties of these particles are then averaged over a size distribution to produce values that describe an ensemble of different sized particles. These values are then used as an internal medium in an olivine single particle, modeled using SIRIS. Light-scattering properties of different sized olivine particles are then averaged over their respective size distribution. The values of the size averaged olivine particles are then used to construct a multiparticle regolith media. The regolith media simulations are run using both SIRIS and RT-CB. RT-CB takes coherent backscattering into account in the modeling, and is thus suited for polarization modeling. Spectra are modeled using SIRIS, which is computationally lighter.

Initially the troilite was replaced by iron in the models. Troilite is a rare mineral in Earth’s crust and mostly found in meteorites. Troilite’s light-scattering properties have thus not been properly characterized, and its refractive index not accurately derived. In Moreau et al. [9], troilite has been synthesized, and from these samples the refractive index of troilite will be derived in the 400 nm – 2500 nm region. To derive the refractive index, the same method from Martikainen et al. [8] will be used. Ground and sieved troilite’s reflectance spectra will be measured. The spectra will then be modeled using multiparticle media, with varying refractive index values to find a best match between measurements and simulations.

A model is created that explains the scattering properties of the CY meteorite samples. The model for the meteorites is then compared to the observations of Phaethon. Model values representing particle size and roughness, composition, and porosity are optimized against Phaethon’s spectra and polarization data, especially focusing on explaining the surface heterogeneity between the hemispheres. The model can also be used to study the connection between Phaethon and Pallas by fitting it to spectral and polarization data from Pallas.

[1] F. L. Whipple, "1983 TB and the Geminid Meteors", International Astronomical Union Circular, Volume 3881, 1983.

[2] I. P. Williams, Z. Wu, "The Geminid meteor stream and asteroid 3200 Phaethon", Monthly Notices of the Royal

Astronomical Society, Volume 262, 1993.

[3] E. MacLennan, S. Marshall, Mikael Granvik, "Evidence of surface heterogeneity on active asteroid (3200)

Phaethon", Icarus, Volume 388, 2022.

[4] E. MacLennan, M. Granvik, "Thermal decomposition as the activity driver of near-Earth asteroid (3200)

Phaethon", Nature Astronomy, 8, 60–68, 2024

[5] A.J. King, H.C. Bates, D. Krietsch, H. Busemann, P.L. Clay, P.F. Schofield, S.S. Russell, "The Yamato-type (CY)

carbonaceous chondrite group: Analogues for the surface of asteroid Ryugu?", Geochemistry, Volume 79, Issue

4, 2019.

[6] K. Muinonen, T. Nousiainen, H. Lindqvist, O. Muñoz, G. Videen, "Light scattering by Gaussian particles with

internal inclusions and roughened surfaces using ray optics", Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative

Transfer Volume 110, 2009.

[7] K. Muinonen, "Coherent Backscattering of Light by Complex Random Media of Spherical Scatterers: Numerical

Solution", Waves in Random Media 14(3), 2004.

[8] J. Martikainen, A. Penttilä, M. Gritsevich, H. Lindqvist, K. Muinonen, "Spectral modeling of meteorites at

UV-vis-NIR wavelengths", Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer, Volume 204, 2018.

[9] J.-G. Moreau, A. Jõeleht, J. Aruväli, M.J. Heikkilä, A.N. Stojic, T. Thomberg, J. Plado, S. Hietala, "Bulk synthesis of

stoichiometric/meteoritic troilite (FeS) by high-tempera

How to cite: Vuori, M., Penttilä, A., Muinonen, K., MacLennan, E., and Granvik, M.: Modeling the surface properties of asteroid (3200) Phaethon using CY-chondrite meteorites, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1582, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1582, 2025.

Lunar swirls are bright areas on the otherwise darker mare regions on the Moon. Our current study focuses on the Reiner Gamma swirl, centered slightly north of the equator and on the side facing Earth, at coordinates 7.5°N, 59.0°W. We are using the same data as prior research to the lunar swirl, namely the data in Weirich et al. (Planet. Sci. J. 4, 212, 2023) and Domingue et al. (Planet. Sci. J. 5, 161, 2024).

Our analysis of photometric data and the use of the particulate medium (PM) model (Muinonen et al., A&A 531, A150, 2011; Wilkman et al., PS&S 118, 255, 2015) follows our approach with the surface of Mercury (Björn et al., Planet. Sci. J. 5, 260, 2024). However, there is a difference in the extent of the area being examined: here, we apply the methods to a localized area on the Moon, as opposed to the average Mercury surface as in Björn et al. (2024). In addition, the amount of data is orders of magnitude larger than the Mercury data, which prevents the use of the same pipeline as before. Therefore, we use a Python-language implementation, healpy (Zonca et al., J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1298, 2019), of the HEALPix discretization (Górski et al., Astrophys. J. 622, 759, 2005) to reduce the number of data points by averaging the reflectance inside a bin in the incidence-emergence-azimuth angles. We utilize the Reiner Gamma swirl mapping results of Chuang et al. (Planet. Sci. J. 3, 231, 2022) to separately examine areas, or ”units”, with different brightnesses: the bright on-swirl unit, the dark off-swirl unit, and the transitionary diffuse-swirl unit.

To deduce physical properties of the regolith of Reiner Gamma, we apply the PM model to photometric data. The model describes a regolith with a fractional Brownian motion surface, which characterizes well the surface roughness of atmosphereless bodies in the Solar System (Muinonen et al., 2011). The model has three geometry parameters: the packing density v, the fractal Hurst exponent H, and the amplitude of height variation σ. Figure 1 shows the effects that the geometry parameters have on the regolith.

Our preliminary results for a subset of the data suggest that the diffuse-swirl regolith around Reiner Gamma is similar in surface roughness but less densely packed than Mercury’s regolith: v ≈ 0.44, H ≈ 0.60, σ ≈ 0.10. For comparison, the packing density of the regolith of Mercury was derived to be v = 0.547±0.004 (Björn et al., 2024). In the future, we plan to extend the analysis to photometric data of the Mare Ingenii swirl (33.7°S, 163.5°E) as well.

How to cite: Björn, V., Muinonen, K., Penttilä, A., Domingue, D., Weirich, J., Chuang, F., and Surkov, Y.: Photometric modeling of the regolith in the Reiner Gamma lunar swirl, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1339, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1339, 2025.

1. Introduction

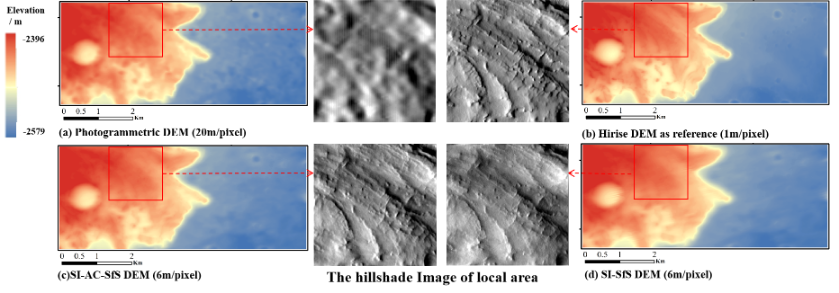

Accurate and high-resolution digital elevation models (DEMs) are essential for Martian landing site selection and geological analysis [1]. However, existing photogrammetric DEMs suffer from low resolution and limited coverage[2]. Traditional shape from shading (SfS) recovers pixel-scale terrain details based on surface reflectance model[3]. However, Martian atmospheric scattering distort image brightness, making it unreliable for representing actual terrain-induced variations, thereby reducing reconstruction reliability[3,4]. Current atmospheric correction methods rely on external sources such as the Mars Climate Database (MCD), or estimated through optimization, which are resolution-limited and unstable[5,6]. To address these limitations, a novel single-image shape from shading method with atmospheric correction (SI-AC-SfS) is proposed to generate high-resolution DEMs by integrating reflectance model into an atmospheric framework[6]. It estimates optical depth using a shadow-based inversion and simulates scattering parameters via the Discrete Ordinate Radiative Transfer (DISORT), eliminating reliance on external products[7]. Applied to a single Context Camera (CTX) image and a low-resolution DEM, it generates a high-resolution DEM with enhanced surface detail and higher accuracy compared to traditional SI-SfS, as validated against the HiRISE reference DEM.

2. Method

The proposed SI-AC-SfS method aims to reconstruct high-resolution DEMs of the Martian surface with improved geometric accuracy by correcting for atmospheric effects. The overall workflow comprises three main steps: 1) joint modeling of atmospheric scattering and surface reflectance; 2) atmospheric parameter estimation from image information and DISORT; and 3) construction and optimization of the SI-AC-SfS loss function. The method takes as input a single preprocessed CTX image and a low-resolution DEM and produces a refined high-resolution DEM.

3. Test data

The experimental analysis of the proposed SI-AC-SfS method was conducted using a single CTX image (6 m/pixel) and the corresponding photogrammetric DEM (20 m/pixel) to generate a high-resolution DEM (6 m/pixel). Evaluation was performed against a HiRISE DEM (1 m/pixel). The study site, located at the Perseverance rover landing site in Jezero Crater (18.41°N, 77.69°E), spans 7.08 km × 2.94 km. The CTX image was preprocessed (e.g., radiometric calibration) using ISIS3 software and manually registered to the photogrammetric DEM. Atmospheric optical depth and scattering parameters of the CTX image were estimated using a shadow-based inversion method and DISORT simulations, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the CTX image properties and atmospheric conditions.

Table 1. Basic information of the used image in the experimental

| Image ID | Image time | Incidence angle | Emission angle | Pixel resolution | solar azimuth | Optical Depth |

|

F05_XN_20N282W |

2014-08-16 |

57.34° |

8.88° |

5.62m |

256.49° |

0.32 |

4. Results

Figure 1 shows the input, generated, and reference DEMs. Both SI-SfS and SI-AC-SfS results contain more detailed information compared to the photogrammetric DEM, demonstrating their ability to reconstruct fine-scale topography. However, it is important to note that hillshade images reflect only enhanced surface details, and the geometric accuracy of the reconstructed DEM must be quantitatively assessed using a reliable reference DEM.

Figure 1. The input photogrammetric DEM and the generated DEM.

Table 2 summarizes the quality metrics of different DEMs. Although the traditional SI-SfS method yields a high PCC (0.83), it exhibits a larger RMSE than the initial DEM, indicating that uncorrected atmospheric scattering leads to visually plausible but geometrically inaccurate results. In contrast, the proposed SI-AC-SfS method achieves the lowest RMSE (3.74 m), MAE (2.91 m), and MAD (19.33 m) when compared with the HiRISE DEM. These results demonstrate that while SI-SfS enhances surface detail, atmospheric correction is crucial for ensuring geometric accuracy in high-resolution Martian DEMs.

Table 2. Overall quality metrics of the different DEMs.

|

Photogrammetric DEM |

SI-SfS DEM |

SI-AC-SfS DEM |

HiRISE DEM |

|

|

RMSE(m) |

4.03 | 4.09 | 3.74 | N/A |

|

MAE(m) |

3.12 | 3.12 | 2.91 | N/A |

|

MAD(m) |

24.75 | 20.89 | 19.33 | N/A |

|

PCC |

0.63 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.79 |

RMSE represents root mean square error; MAE represents mean absolute error; MAD represents maximum absolute deviation; PCC represents pearson correlation coefficient.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

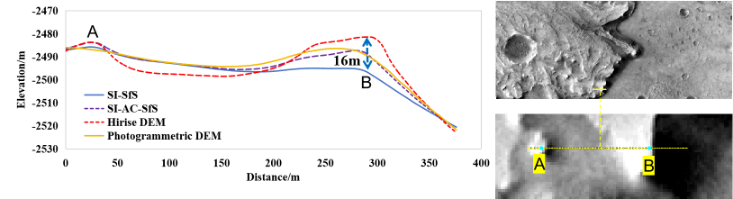

Figure 2 presents a profile comparison from different DEMs to assess the effect of atmospheric correction. In the traditional SI-SfS result, image brightness caused by atmospheric scattering is misinterpreted as terrain variation, resulting in inaccurate elevation reconstruction at points A and B. In contrast, the proposed SI-AC-SfS DEM profile aligns more closely the HiRISE DEM, with a lower MAD (3.32 m) than SI-SfS (5.19 m) and the photogrammetric DEM (3.46 m).

Figure 2. Profile comparison across different DEMs.

This study proposes the SI-AC-SfS method, which integrates an atmospheric scattering framework with optical depth and scattering parameters derived through a shadow-based inversion and DISORT simulation, effectively overcoming the traditional SI-SfS limitation of misinterpreting image brightness caused by atmospheric scattering as terrain variation. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed SI-AC-SfS method is effective in generating reliable, high-resolution DEMs on Mars, providing critical support for future exploration missions. Future work will focus on the extension to a multi-image shape and albedo from shading framework with atmospheric correction to more effectively account for atmospheric scattering and albedo variations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 42221002 and 42101447. The authors would like to thank the MRO CTX and HiRISE teams (htt ps://ode.rsl.wustl.edu/mars/), as well as the developers of the open-source DISORT (https://github.com/LDEO-CREW/Pythonic-DISORT) and ISIS3 (https://isis.astrogeology.usgs.gov/).

References

[1] Lorenz R D. 2023. AdSpR. 71. 1. [2] Heipke C, Oberst J, Albertz J, et al. 2007. P&SS. 55, 14. [3] Alexandrov, O., & Beyer, R. A. 2018. E&SS. 5, 652. [4] Qian, J., Ye, Z., Qiu, S., et al. 2025. Icar, 25, 116494. [5] Liu, W. C., & Wu, B. 2023. JPRS. 204, 237. [6] Hess, M., Tenthoff, M., Wohlfarth, K., & Wöhler, C. 2022. JIm. 6, 158. [7] Shaheen, F., Scariah, N. V., Lala, M. G. N., et al. 2022. Icar. 388, 115.

How to cite: Qian, J., Ye, Z., Xu, Y., Huang, R., and Tong, X.: Single-image Shape and from Shading with Atmospheric Correction for Precise Topographic Reconstruction on Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-849, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-849, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Planetary formation theories aim to explain the evolution of planets from the proto-planetary disk. Comets are thought to be primitive remnants that never accreted into planets and now reside in the Oort cloud and Kuiper belt. Their highly elliptical orbits shield them from solar radiation for most of their lifetimes, preserving their original composition. As such, comets offer a unique window into the early Solar System. Investigating their internal structure and composition can provide critical tests for models of planetary formation.

Previous in-situ missions have employed infrared (IR) spectroscopy and ground-penetrating radar to study cometary nuclei. While radar can probe below the surface, its spatial resolution is limited by long wavelengths. Conversely, IR provides high spatial resolution but lacks subsurface penetration. Terahertz (THz) time-domain spectroscopy offers a promising middle ground, combining centimeter-scale penetration with millimeter-scale resolution. Moreover, key molecular species, such as amino acids detected on comets, exhibit distinctive absorption features in the THz range.

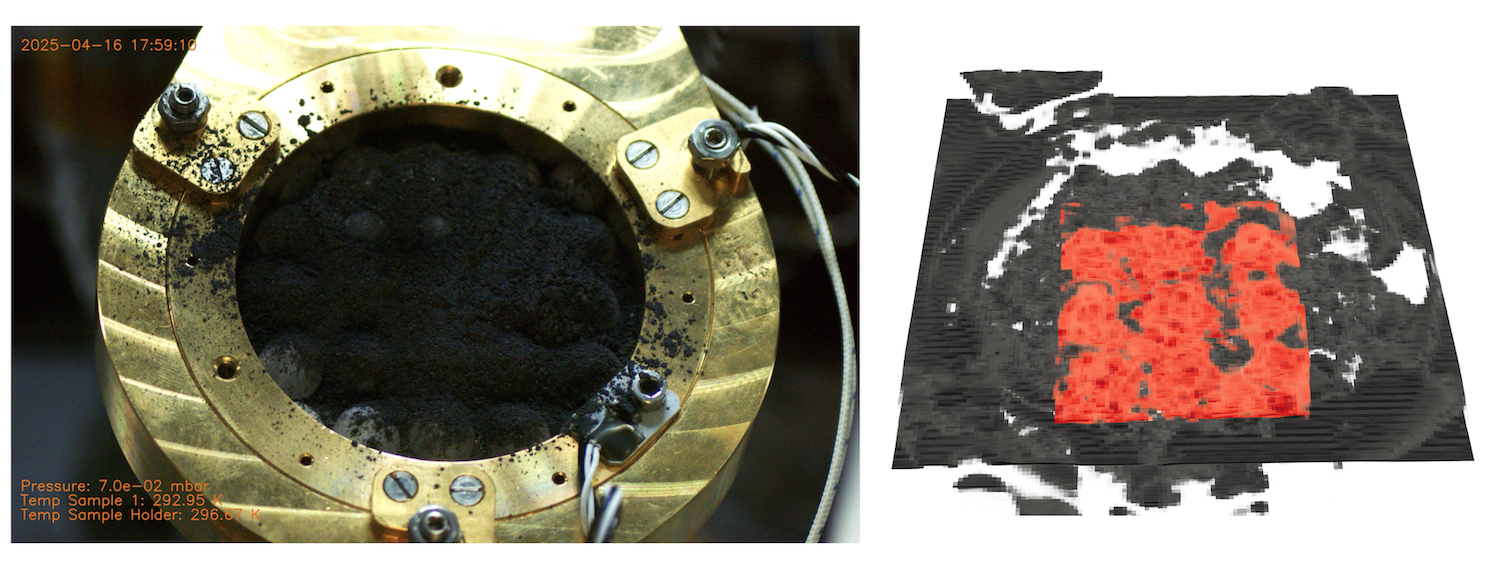

As part of the SUBICE project, we are investigating the suitability of THz time-domain spectroscopy for in-situ space applications. For that purpose, we built a laboratory setup called COCoNuT (Characteristic Observation of Cometary Nuclei using THz-spectroscopy) [1]. COCoNuT can simulate the conditions found on comets in a thermal vacuum chamber and houses a commercial THz time domain spectrometer. Using cometary simulants, we conduct proof-of-concept experiments to assess the viability of this technique for future space missions [2].

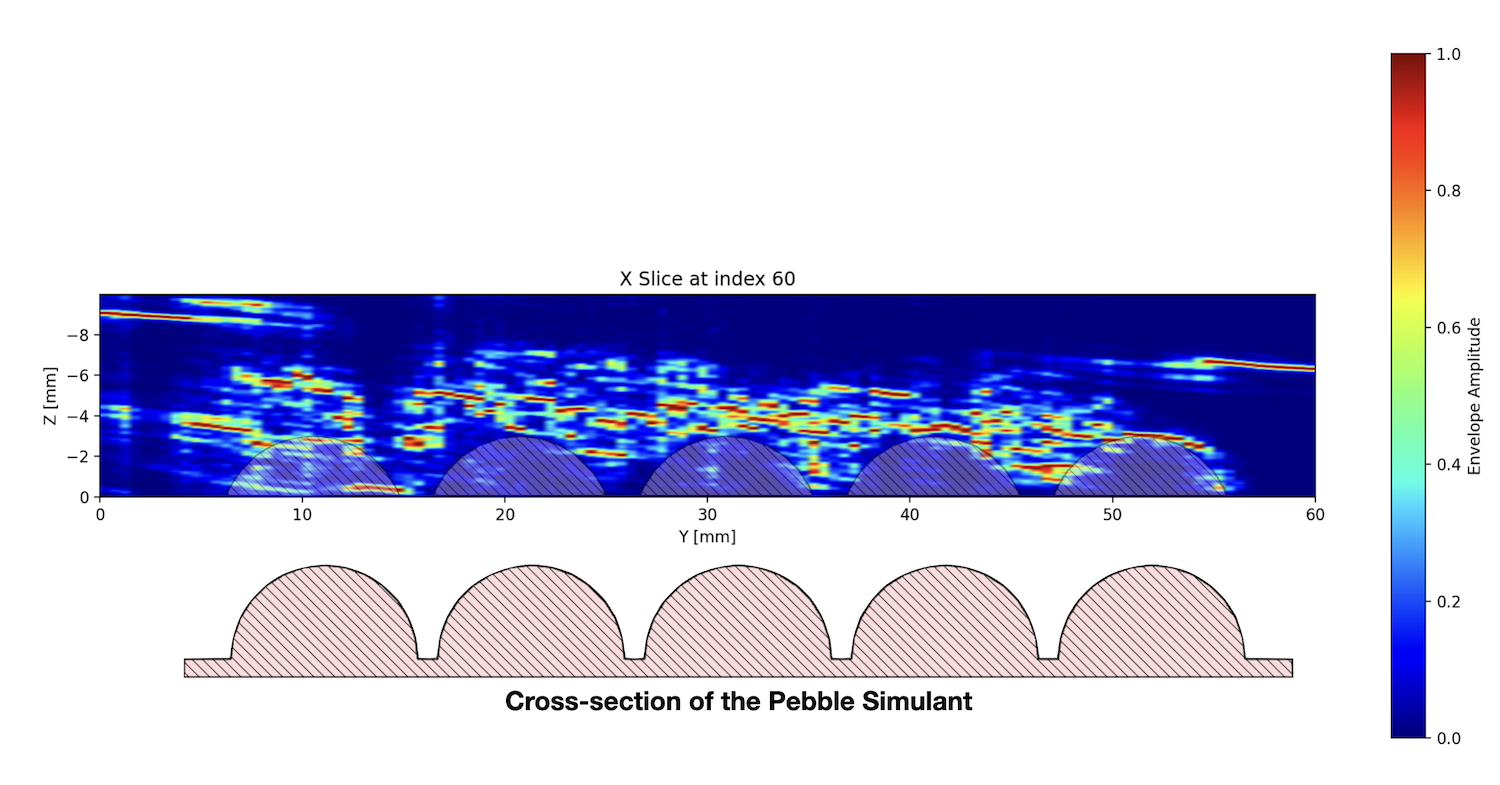

Figure 1: Pebble simulant printed out of Cyclic-Olefin-Copolymer (COC) and covered with cometary dust analogue (SiO2/charcoal, 9:1 mixture). The 3D THz scan with the reconstructed pebbles in red is shown to the right.

Figure 2: A slice of the cometary simulant scan. The cross section of the pebble simulant is shown below and also overlayed. The sample holder top surface is visible on the sides of the scan as a straight line. The pebbles are clearly visible as voids in the scan.

Initial measurements of ice-analogues and SiO2/charcoal dust shows that we can reconstruct pebbles located underneath the dust layer as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

We will present measurements with porous ice and ice pebbles along with olivine dust analogues.

References:

[1] Linus Leo Stöckli, Mathias Brändli, Daniele Piazza, Rafael Ottersberg, Antoine Pommerol, Axel Murk, Nicolas Thomas; Design and commissioning of a THz time-domain spectro-goniometer in a cryogenic comet simulation chamber. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1 March 2025; 96 (3): 034502. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0252742

[2] Pommerol, A., Jost, B., Poch, O. et al. Experimenting with Mixtures of Water Ice and Dust as Analogues for Icy Planetary Material. Space Sci Rev 215, 37 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-019-0603-0

How to cite: Stoeckli, L., Demion, A., Belousov, D., Meier, V., Nicollerat, M., Girard, H., Ottersberg, R., Pommerol, A., Moerschell, J., Murk, A., and Thomas, N.: The potential of in-situ THz-spectroscopy to resolve the subsurface structure of Comets, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1297, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1297, 2025.

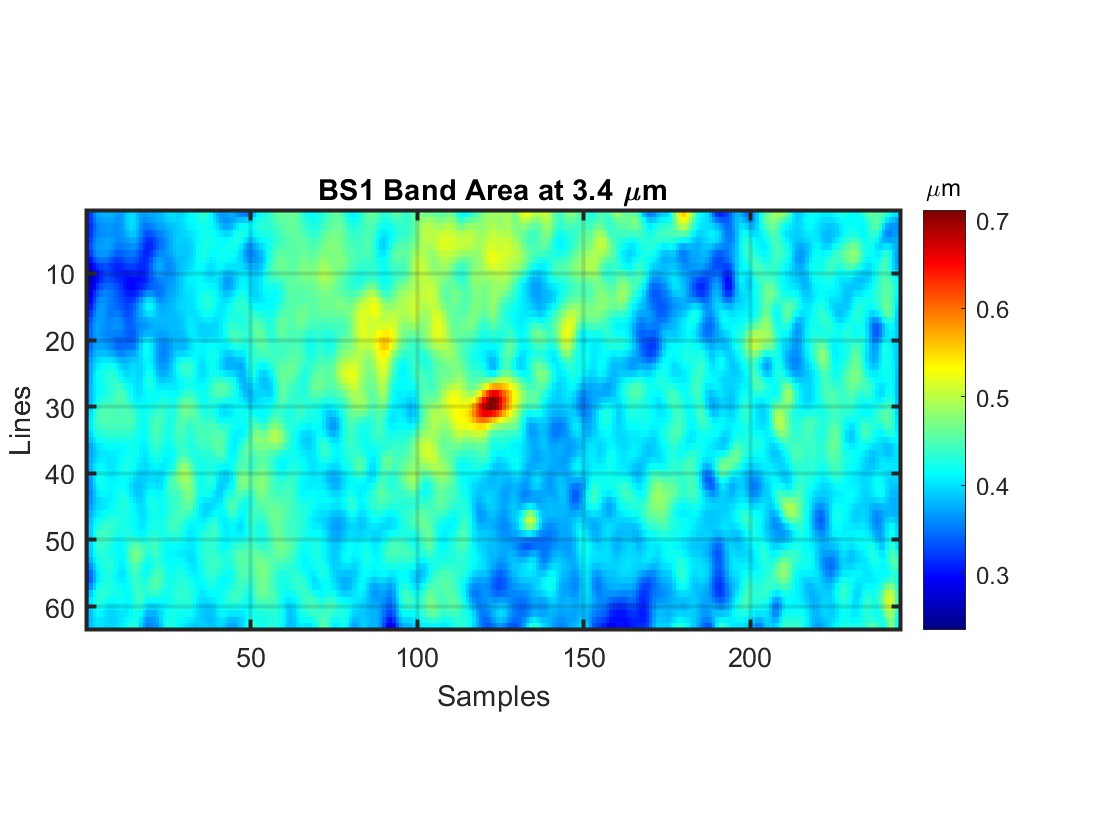

Introduction: The surfaces of airless bodies, such as asteroid (101955) Bennu, are typically composed of a regolith mixture containing both coarse and fine particulates. Observations from NASA’s Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) mission demonstrated a discontinuity between the remote sensing derived thermophysical properties and thermal spectroscopy results, indicating that a fine layer of dust may be coating the large boulders and coarse regolith surface [1]. To better understand the impact of such a coating on the thermal infrared spectra measured at Bennu, this work developed experimental methods for simulating dust coverings using Space Resource Technology’s CI simulant, based on the bulk composition of the Orgueil meteorite [2].

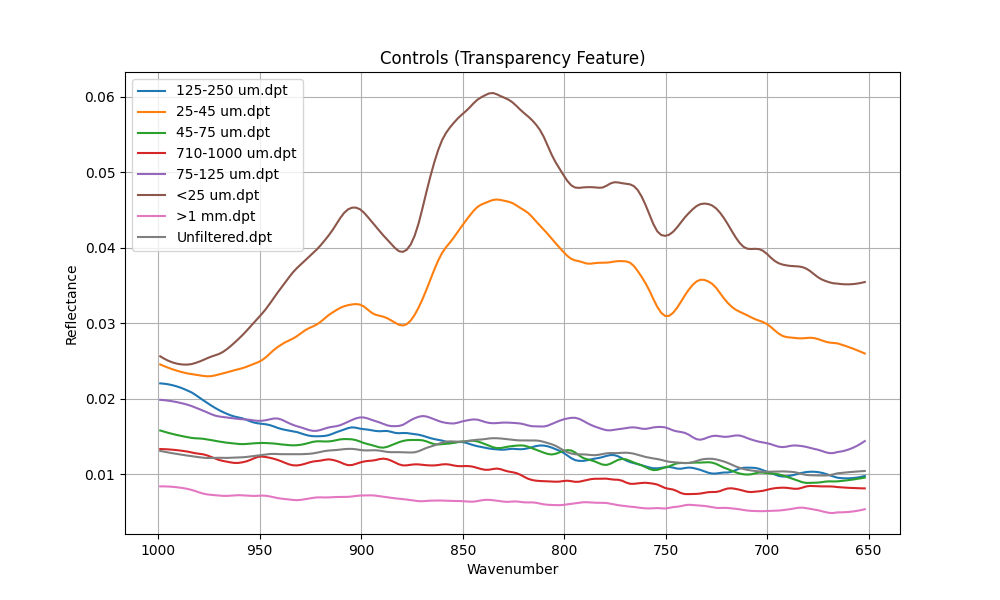

Figure 1: FTIR Reflectance Spectra of Control Samples of CI simulant.

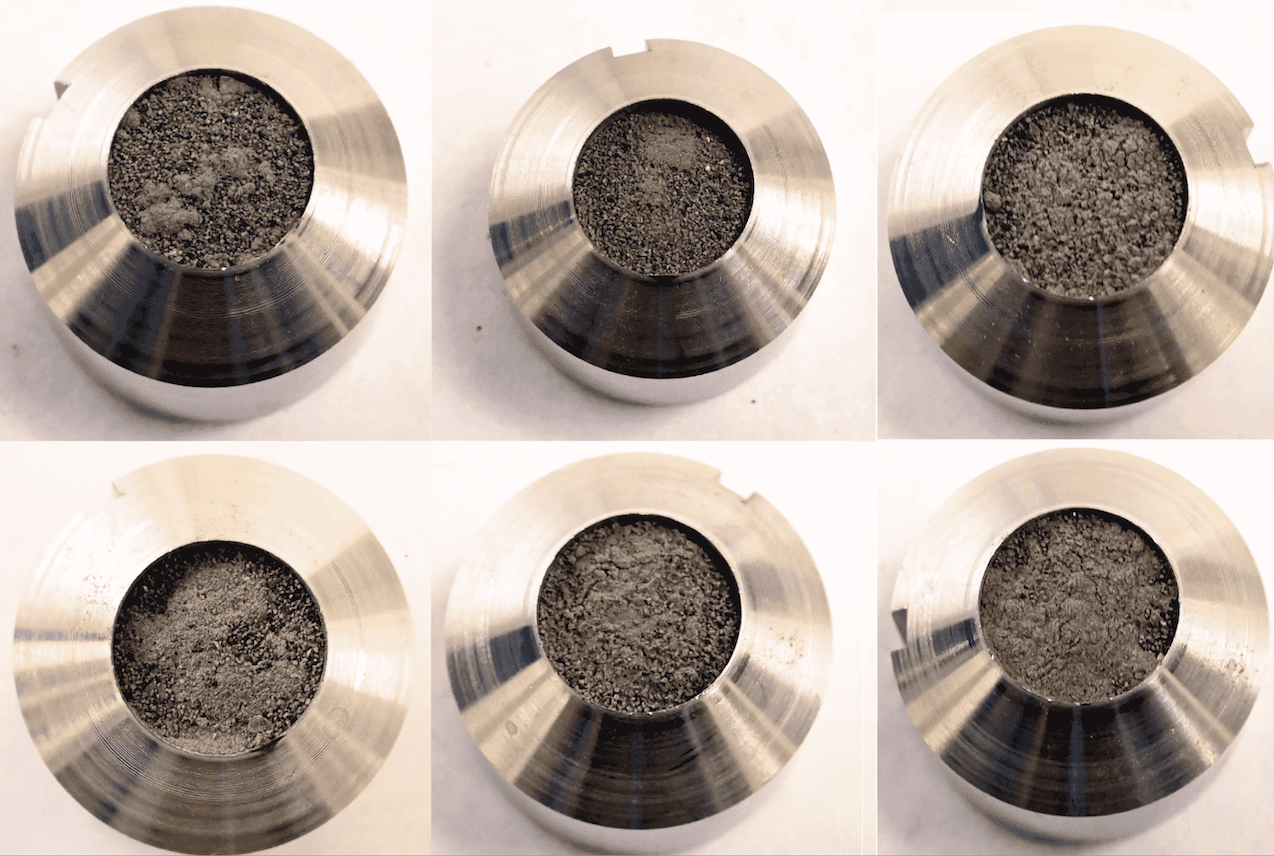

Figure 2: Figure 2: Microscope Camera Images of Sample Surfaces (7%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, 50% Fines wt) of CI simulant

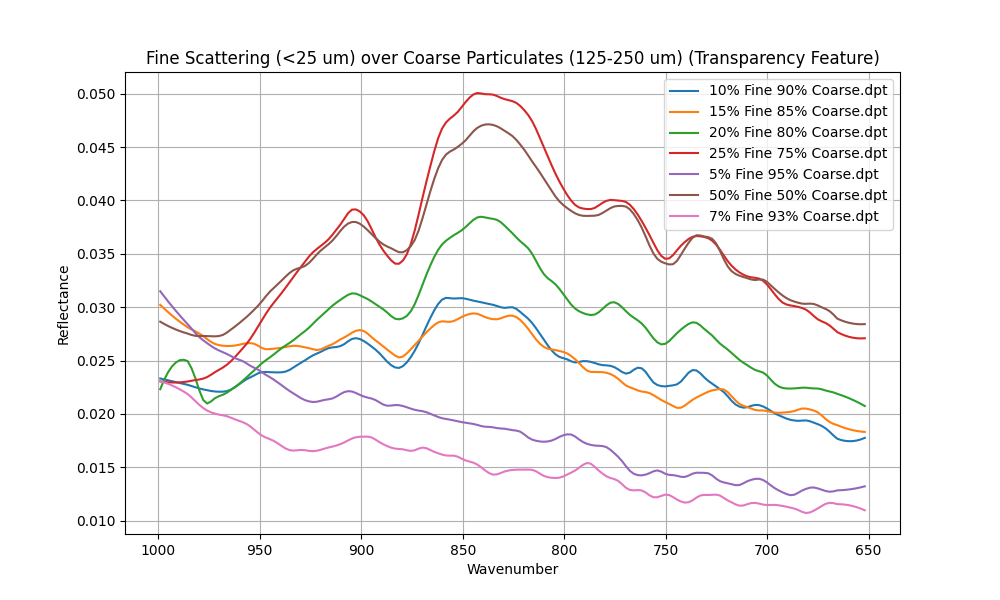

Methods: The CI simulant was first sieved into seven size fractions: <25, 25-45, 45-75, 75-125, 125-250, 710-1000, and >1000 mm. An unsieved sample was used as a control. The spectra of the eight samples were measured using a Bruker Vertex 70v Fourier Transform Infrared Reflectance (FTIR) spectrometer, normalized using a gold standard prior to and after measurements, in the range of 1000-650 cm-1 (Figure 1). The dust coating was simulated by placing increasing mass fractions of fine particulates (<25 mm) onto coarse particulates (125-250 mm) using tweezers. Images were collected using a mirrorless Nikon Z6III microscope to capture surface roughness features (Figure 2). The dust layers were measured at approximately 5%, 7%, 10%, 15%, 20%, 25%, and 50% fines by total mass in the FTIR spectrometer (Figure 3).

Figure 3: FTIR Reflectance Spectra of Fine-Dusted Samples of CI simulant.

Results: Clumping of Fines: The fine particles of the CI simulant used are particularly susceptible to clumping, likely owing to elevated electrostatics interparticle forces. The result is an uneven covering of dust across the surface of the samples (Figure 2), causing heterogeneity across the top layer of the sample. Future work aims to reduce this clumping effect by using alternative dust deposition mechanisms, including sieves, electrically charged tubes, and air circulation chambers.

Controls: As shown in Figure 1, the spectra fell within two categories: spectra with evidence of a Transparency Feature (TF) ( <45 mm) and those without (>45 mm). This switch is indicated by the appearance of broad transparency features, such as the minimum around 875 and the broad peak around 835 cm-1. Furthermore, the Reststrahlen bands, associated with the vibrational modes of silicates, around 750 cm-1, become more apparent with decreasing particle size.

Fine Coatings ( <45 mm): The simulated dust coatings provided insight into the amount of fines, by mass, required to see fine-dominated spectral features in the overall spectra of the regolith samples. We discovered that very little (>7% wt) fine coverage was required to begin dominating the spectra (Figure 3), indicating that even small amounts of dust coverings could have visible effects on the spectra (e.g. the emergence of TFs and >10% change in the spectral slope).

Implications for OSIRIS-Rex Findings: From the data returned by the OSIRIS-Rex Thermal Emission Spectrometer (OTES) [3], thermal inertia modelling imply that the surface is porous;, however, the spectral findings indicate that the surface is composed of non-porous? rocks with thin dust coatings [4]. Our experiments find that as little as ~7 wt % of <25 µm fines can impose a fine-dominated spectral signature on a 125–250 µm substrate, meaning that spectrally visible coatings on Bennu can be achieved by dust layers only a few microns thick. Therefore, a thin, laterally discontinuous coating could reconcile the difference between Bennu’s rock-controlled thermal inertia and the fine-grained spectral observations measured by OTES. Incorporating wavelength-dependent transmissivity for 10-50 µm coatings could therefore refine surface property constraints for Bennu.

Conclusion: We found that a negligible mass fraction (>7% wt) was sufficient to overwhelm and dominate mid-infrared emissivity spectra. The results indicate that the discontinuity in OTES data could be linked back to dust coating on the larger rocks and boulders.

References: [1] Tinker C. et al. (2023) RAS Techniques and Instruments (Vol. 2, Issue 1). [2] Landsman Z. et al. (2020) EPSC 2020. [3] Christensen P. R. et al. (2018) Space Science Reviews (Vol. 214, Issue 5). [4] Rozitis B. et al. (2022) JGR: Planets (Vol. 127, Issue 6). [5] Rivera-Hernandez F. et al. (2015) Icarus (Vol. 262).

How to cite: Belhadfa, E., Bowles, N., and Shirley, K.: Quantifying Thin Dust Layer Effects on Thermal-IR Spectra of Bennu-Like Regolith: FTIR Experiments with CI Asteroid Simulant , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-531, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-531, 2025.

1 - Introduction

Understanding the geological processes is a key objective for future lunar exploration. The ESA Màni mission aims to advance this understanding by characterizing the lunar regolith with high resolution imagery, Digital Elevation Model and photometry. This study focuses on the photometric behavior of lunar areas across multiple regions, leveraging an advanced model to estimate the best satellite mission scenario to predict the microphysical properties. At the core of this investigation is the use of the Hapke radiative transfer model [1], a widely used semi-empirical approach for light interaction.

Similar photometric studies on other planetary bodies, such as Europa Mars [2][3] and Europa [4], have demonstrated the effectiveness of multi-angle reflectance observations combined using inversion techniques for retrieving surface microtexture.

Through the application of the Bayesian Monte-Carlo inversion framework [5], we used the mc3 inversion tool [6] and quantified the surface properties that govern the scattering and absorption of light. Particular attention is paid to the efficiency and biases associated with the photometric sampling, following the findings of [7], and to the light-scattering behavior of surfaces as previously explored in experimental study [8].

2 - Method

2.1 - Mission orbit design

The Màni mission will employ a multiple-pass polar orbit strategy, at an altitude of 50 km. The repeated high-resolution data collected will contribute to a deeper understanding of lunar geology and support the broader goals of lunar exploration, including future manned missions and resource utilization.

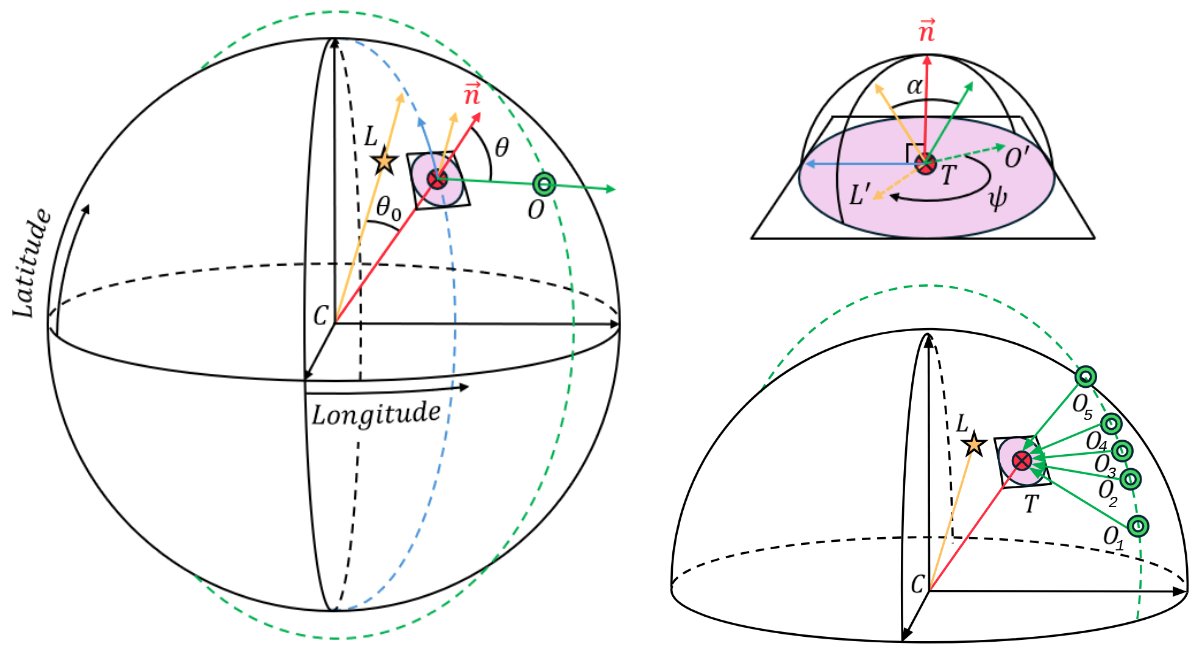

We assume here the Moon as a perfect sphere. The left side of the Figure 1 represents a global view of the Moon and the mission. Here, the yellow star symbol (L, for light source) represents the subsolar point of the Sun on the surface, the green circle symbol (O, for observer) represents the observer point, which is the location of the satellite and the red circle symbol (T, for target) shows the target position. This configuration reveal crucial angles such as incidence (θ), emergence (θ0), phase (α) and azimuth (ψ) used to calculate and inverse the reflectance.

Figure 1 : System coordinates and geometries used for a given scenario. The right figure represents a zoom on the normal plan from the target normal vector (n).

A total of 93 plausible mission geometry were created, with a target at nadir, medium and high latitudes (0o,45o,70o) with different orbits longitudes (−10o,0o,10o).

2.2 - Surface photometry

For the target surface, a variety of 12 photometric microstructure surfaces using different single scattering albedo (ω), Hapke mean slope roughness (ζ), opposition effect amplitude (B0), asymmetry parameter (b), back scatter fraction (c) and opposition effect width (h) are set. To simulate the mission, we combined all the geometries and photometries to make a single dataset of 1116 different scenarios. By evaluating these scenarios, we aim to better understand how photometric behavior varies under different microphysical conditions, informing the optimal choice of parameters for the mission’s orbital configurations.

2.3 - Efficiency

To simulate the mission, we combined all the geometries and photometries to make a single dataset of 1116 different scenarios. We evaluate each scenarios by using the efficiency (E) using the strategy defined in [8]. The main steps are described here after. (i) The reflectance corresponding to each of the 1116 different scenarios (all combinations of possible 93 geometry and 12 photometry) are computed. (ii) For each one of them, the Bayesian inversion is performed, incorporating noise level of 10% and 2%. (iii) The quality of the knowledge on the photometric parameters is estimated by the efficiency "E". The closer the solution to the true parameter set is, the better the estimate. We measure the quality of the tested geometry by considering, for every parameter (for example ω′), the part of the distribution σ(ω′) which lies inside the interval [σ(ω′) − ϵ, σ(ω′) + ϵ], where ϵ is set to 1% of the total parameter space.

3 - Results and Simulations

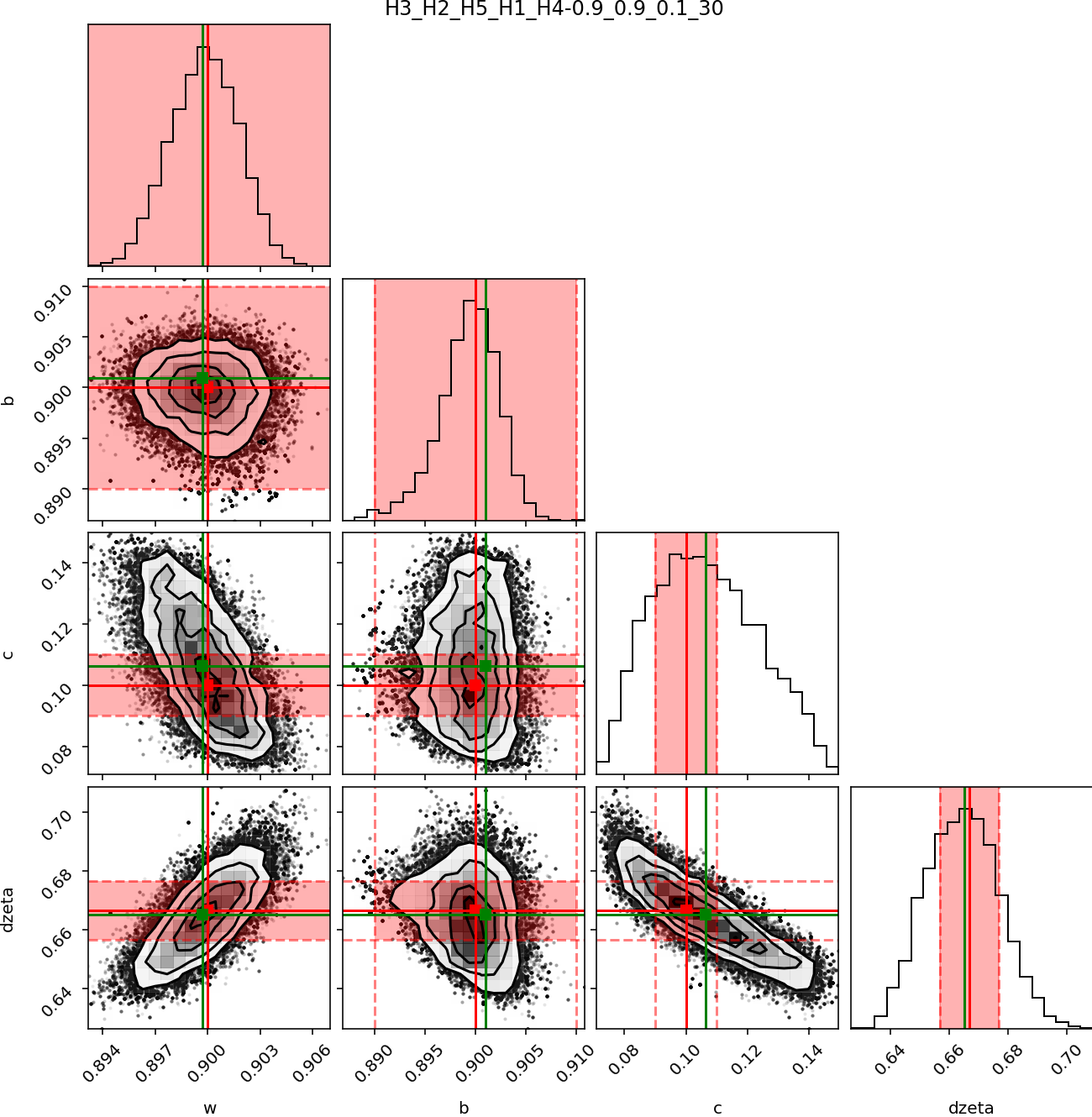

Figure 2 shows an example of the knowledge on the photometric parameter in one example out of the 1116 scenarios. Given the noise level, a significant fraction of the solutions are outside the ϵ =1% acceptable domain but the maximum likelihood is close to the true solution. The proxy is respectively 2.65 and 6.41 for this example.

Figure 2 : Results of the mc3 tool for the inversion of the synthetic reflectance at an SNR of 10% for a combination of 5 orbits with a target at 70o latitude for a surface photometric property of (ω=0.9, b=0.9, c=0.1 and ζ=30) and (ω=0.3, b=0.3, c=0.9 and ζ=30).

This approach enables the explicit identification of the incidence, emergence and phase angle combinations that are most effective in predicting the physical parameters of a given type of microtexture. By comparing the proxy value, we demonstrate that 25 observations (5 observations for each of 5 orbit) at 10% noise level contains less information that 15 observations (5 observations for each of 3 orbit) at 2% noise level.

4 - Conclusions

This results provide critical insights into the optimal orbital geometries and observation strategies needed to robustly retrieve lunar surface properties. By identifying the most effective measurements configurations, this work lays the foundation for enhancing the scientific return of future photometric missions, contributing to a deeper understanding of the Moon’s regolith evolution and aiding the preparation for upcoming exploration activities.

References

[1] H. Sato et al. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 2014.

[2] J. Fernando. Thesis, Université Paris Sud - Paris XI, 2014.

[3] J. Fernando et al. Planetary and Space Science, 2016.

[4] I. Belgacem et al. Icarus, 2020.

[5] K. Mosegaard et al. Journal of Geophysical Research, 1995.

[6] P. Cubillos et al. The Astronomical Journal, 2016.

[7] F. Schmidt et al. Icarus, 2019.

[8] A. F. McGuire et al. Icarus, 1995.

[A] J. Frydenvang et al., this meeting, https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EPSC-DPS2025/EPSC-DPS2025-318.html

How to cite: Lancery, H., Schmidt, F., Andrieu, F., Frydenvag, J., Mosegaard, K., and Fernandes, I.: Optimal Photometric geometries for a space mission, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-267, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-267, 2025.

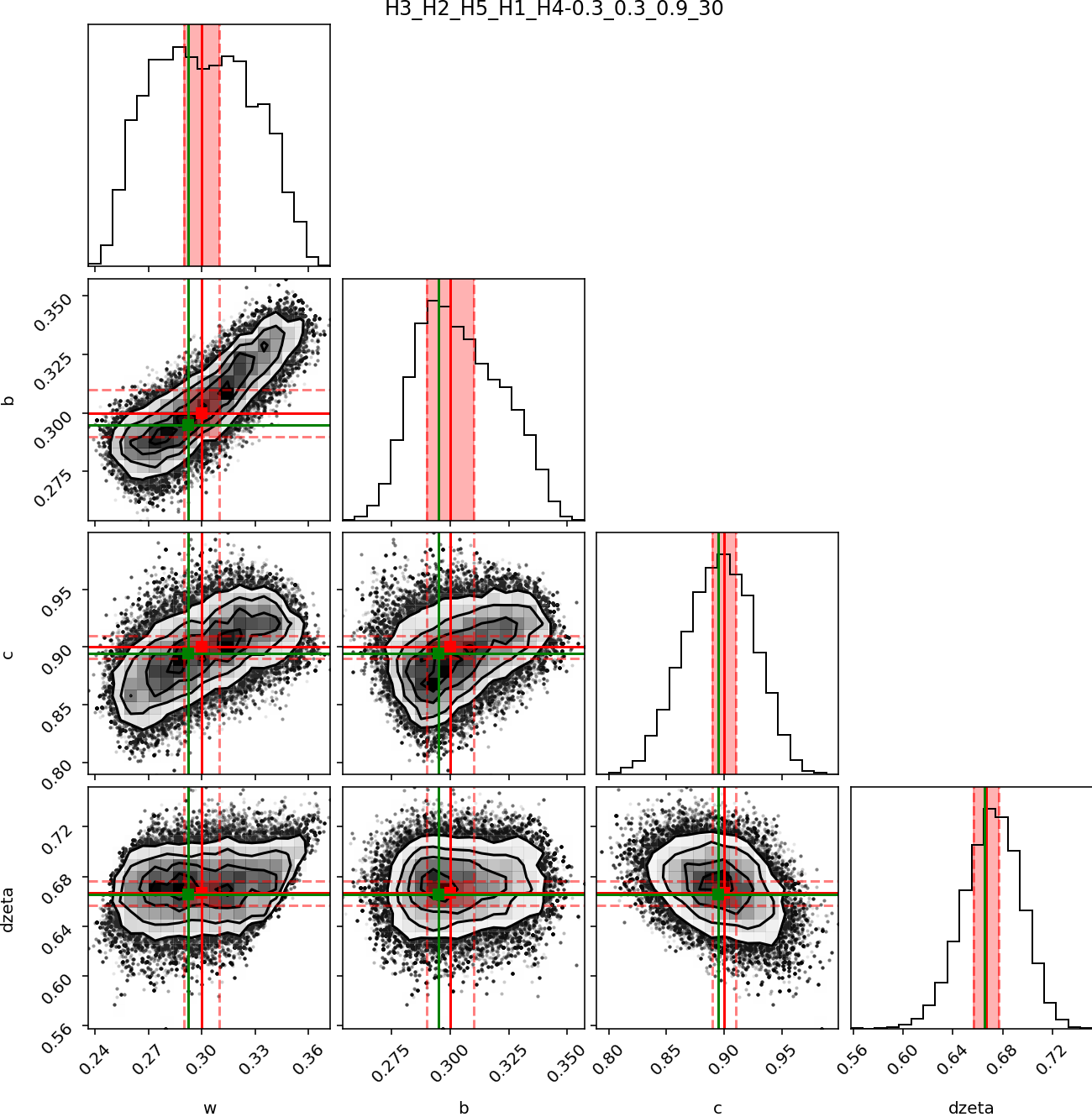

Light scattering by cosmic dust particles is central to interpreting photometric and polarimetric observations in planetary science. The scattering properties of particles are described by the 4×4 scattering Mueller matrix (F). For ensembles of randomly oriented particles and their mirror counterparts, the Mueller matrix reduces to a block-diagonal form with six non-zero angular functions: a₁, b₁, a₂, a₃, b2, and a₄,

These functions encode the angular behavior of scattering and are often derived from theoretical computations or laboratory measurements. However, existing models may violate required symmetry relations or lack flexibility for inverse modeling tasks.

We provide a concept of an explicit parametric model of complex angular dependencies of scattering matrix elements by empirical parameterization of the Mueller matrix based on analytical functions [1]. The model incorporates physical insights, such as forward- and backward-scattering behaviors and backscattering surges, while enforcing symmetry constraints derived from scattering theory [2]. It enables compact representations of the Mueller matrix: measured matrices can be described with as few as 28 free parameters averaging fewer than five per function. The full model supports up to 44 parameters in its most general form for increased flexibility. The model further allows for an efficient transport and utilization of scattering matrices in multiple scattering applications.

The parameter estimation process consists of three stages: initialization, nonlinear least-squares optimization, and uncertainty quantification using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. The MCMC approach allows us to derive statistical distributions for all model parameters, producing confidence intervals and uncertainty envelopes for the modeled scattering matrix elements.

We applied our model to a range of experimental scattering matrices from the updated Granada-Amsterdam Light Scattering Database [3], which includes measurements for cosmic dust analogs such as meteorites, regolith simulants, minerals (e.g., feldspar, hematite, rutile), as well as water ice [4]. Across these samples and wavelengths, the model achieves relative root-mean-square deviations on the order of 1%, demonstrating its robustness and accuracy. The model also enables the extraction of physically meaningful descriptors—such as asymmetry parameters, polarization minima and maxima, and inversion angles—which support interpretation of phase curve dependencies.

In particular, we show that the parameterization accurately reproduces the angular trends in both intensity and polarization, including features like negative polarization branches and forward-scattering peaks. The model handles noisy or incomplete data gracefully, and symmetry enforcement helps reduce overfitting and improve physical plausibility.

Our empirical model serves as a valuable tool for radiative transfer applications, including the modeling of disk-integrated photometric and polarimetric phase curves of atmosphereless Solar System objects (e.g., satellites, asteroids, comets) [5]. The compact parameterization facilitates both forward simulations and inverse retrievals of dust properties. Moreover, it opens possibilities for applying machine learning methods to scattering data analysis, due to its consistent structure and small parameter set.

In conclusion, the presented parameterized Mueller matrix approach enables efficient, physically grounded modeling of light scattering by cosmic dust. It bridges the gap between complex experimental data and practical radiative transfer applications [6,7].

Ongoing work focuses on applying the model to the full Granada-Amsterdam database, developing global trends across materials, and integrating the parameterization into inverse modeling of remote sensing observations.

Figure 1: Measured data and model for feldspar (left) and hematite measured data and model with uncertainty envelope (right).

[1] Muinonen, K. & Leppälä, A, in preparation, (2025)

[2] Hovenier, J.W., van der Mee, C.V.M. (1983). Fundamental relationships relevant to the transfer of polarized light in a scattering atmosphere. Astronomy & Astrophysics 128, 1-16.

[3] Muñoz O., Frattin E., Martikainen J. et al. (2025). Updated Granada-Amsterdam Light Scattering Database. JQSRT 331, 109252.

[4] Muinonen, K. & Markkanen, J. 2023, in Light, Plasmonics and Particles, ed. M. P. Mengüç & M. Francoeur, Nanophotonics (Elsevier), 149–165

[5] N. Kiselev et al., New Polarimetric Data for the Galilean Satellites: Io and Ganymede Observations and Modeling, Planet. Sci. J. 5, 10 (2024)

[6] K. Muinonen, A. Penttilä, Scattering matrices of particle ensembles analytically decomposed into pure Mueller matrices, JQSRT 324, (2024)

[7] K. Muinonen et al., Coherent backscattering in discrete random media of particle ensembles, JQSRT 330, (2025)

How to cite: Leppälä, A., Muinonen, K., Penttilä, A., Muñoz, O., and Videen, G.: Empirical Parameterization of Mueller Matrices for Light Scattering by Cosmic Dust, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-632, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-632, 2025.

Modeling the brightness of a surface consisting of particulate material is a problem we often face in planetary science, but it is also present in many other fields from Earth remote sensing to material science and industrial applications. The forward problem depends on particle sizes, shapes, packing, and the optical properties of the materials. In the inverse problem, we want to estimate some of the mentioned properties from the scattering characteristics of the material.

In general, the forward problem can be difficult if the particulate material has rough structure in many size scales including the scale of the wavelength considered, in which case the Maxwell equations need to be solved for the wavelength scale. However, if the particles are large compared to the wavelength, we can employ a geometric optics approximation to calculate average single-scattering properties of the grains in the material, and a radiative transfer approximation to consider the response of the particulate material.

We have employed the abovementioned modeling to study the effect of particle size and complex refractive index m=n+ik on the reflected intensity of particulate surfaces. The direct application of this method is the inversion of m, and especially the extinction coefficient k, from reflectance measurements with known particle shapes and sizes.

We simulate the forward problem in a grid of input parameters (size, n, and k) and create a library of reflectance values that are integrated over the backward scattering hemisphere of a particulate surface when illuminated directly from above. Particle shape is fixed to a random convex polyhedral shape. Single-particle scattering properties are simulated using the SIRIS[1] geometric optics code, and multiple scattering and the backward hemispherical reflectance with RT-CB[2] code employing only the radiative-transfer part as the coherent backscattering effects are not important here.

We present the results of these simulations and show how the received reflectance can be approximated with a simple, logistic-type function with the size parameter of the particles (size in relation to the wavelength) and the extinction coefficient combined into a single parameter, and the real part not having any significant role in this approximation. The analytical approximation can be used for quick inversion of reflectance measurements for the extinction coefficient with known size or to the size with known extinction coefficient [3]. Finally, we present the predictions using this model for mixtures of Mercury-related endmembers created in the ISSI project “Wide-Ranging Characterization of Explosive Volcanism on Mercury: Origin, Properties, and Modifications of Pyroclastic Deposits” led by A. Galliano, and compare to measurements of the mixtures.

[1] Muinonen et al. (2009). Light scattering by Gaussian particles with internal inclusions and roughened surfaces using ray optics. JQSRT 110, 1628–1639.

[2] Muinonen K, 2004. Coherent backscattering of light by complex random media of spherical scatterers: Numerical solution. Waves in Random Media 14(3), 365-388.

[3] Penttilä et al. (2024). Modeling linear polarization of the Didymos-Dimorphos system before and after the DART impact. The Planetary Science Journal, 5(1), 27.

How to cite: Penttilä, A., Martikainen, J., Vuori, M., and Muinonen, K.: Simple empirical approximation for surface reflectance of particulate materials in geometric optics regime, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-752, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-752, 2025.

Background

For decades, remote sensing has been the most important window to study the surfaces of planetary bodies. Inferring the physical properties like the composition, microstructure and topography of such surfaces based on photometric and spectroscopic observations remains a challenging problem to date.

Laboratory experiments, as well as analytical and numerical models, are used to enable this inversion. Analytical models based on the two-stream approximation in semi-infinite media (e.g. Hapke model) are widely used in the community to fit spectroscopic datasets and infer properties like grain sizes. This approach is at least partially empirical, and the applicability of such models to highly multiple-scattering media like icy regolith is debated.

Numerical models can be grouped into those that calculate the interactions of the light and the scattering media in the geometric optics (GO) regime and those that numerically solve the electromagnetic field equations to reproduce wave effects like diffraction and interference. While both numerical approaches are limited by computational performance, implementations in the GO limit for small systems of hundreds of particles can be solved with tens of CPU hours, while the latter requires high-performance parallel computing with a computational cost in the order of CPU years.

Methods

For simulations in the GO regime, the intersection of the photon path with complicated meshes is the most expensive computational problem. The demand for real-time ray-tracing-based rendering in computer vision and in the gaming industry led manufacturers of graphical processing units (GPU) to develop specialised hardware on the chips to accelerate this step.

We developed a ray-tracing simulation that uses this hardware acceleration and runs purely on the GPU. This allows us to push the boundaries of numerical simulations in the GO regime to laboratory-sized samples consisting of millions of particles and highly multiple scattering systems.

A triangular mesh represents the geometry of the scattering medium. Arbitrary grain shapes and surfaces can be modelled. The geometric optics limit gives the highest meaningful resolution of details at a few times the wavelength. The sample can consist of different materials. The optical properties of each material are given by its real and imaginary index of refraction. This allows the simulation of the interaction of light with regolith samples composed of millions of particles with arbitrary grain shapes, complex microstructures or layered systems without any further assumptions.

The ray-tracing algorithm launches tens of millions of parallel rays into the scene, with all of them having a Stokes vector that tracks the polarisation state. Absorption and scattering are handled probabilistically, the latter by solving the Fresnel equations and Snell’s law at every particle intersection. One ray can scatter many ten thousand times between or inside of particles until it is absorbed or escapes the sample.

The simulation outputs the position of the last intersection, the direction and the Stokes vector of all scattered rays. The location of absorption is saved for all rays that don’t escape the sample. This allows the calculation of the bidirectional reflectance function, the deposition depth of the absorbed energy and the polarisation state of the reflected light. If the simulation is run for a large grid of wavelengths, the reflectance spectrum of the sample can be calculated.

The simulation duration for 10’000’000 rays in a particulate medium consisting of millions of particles with hundreds of scattering interactions per ray is in the order of minutes on a high-end consumer GPU.

Results

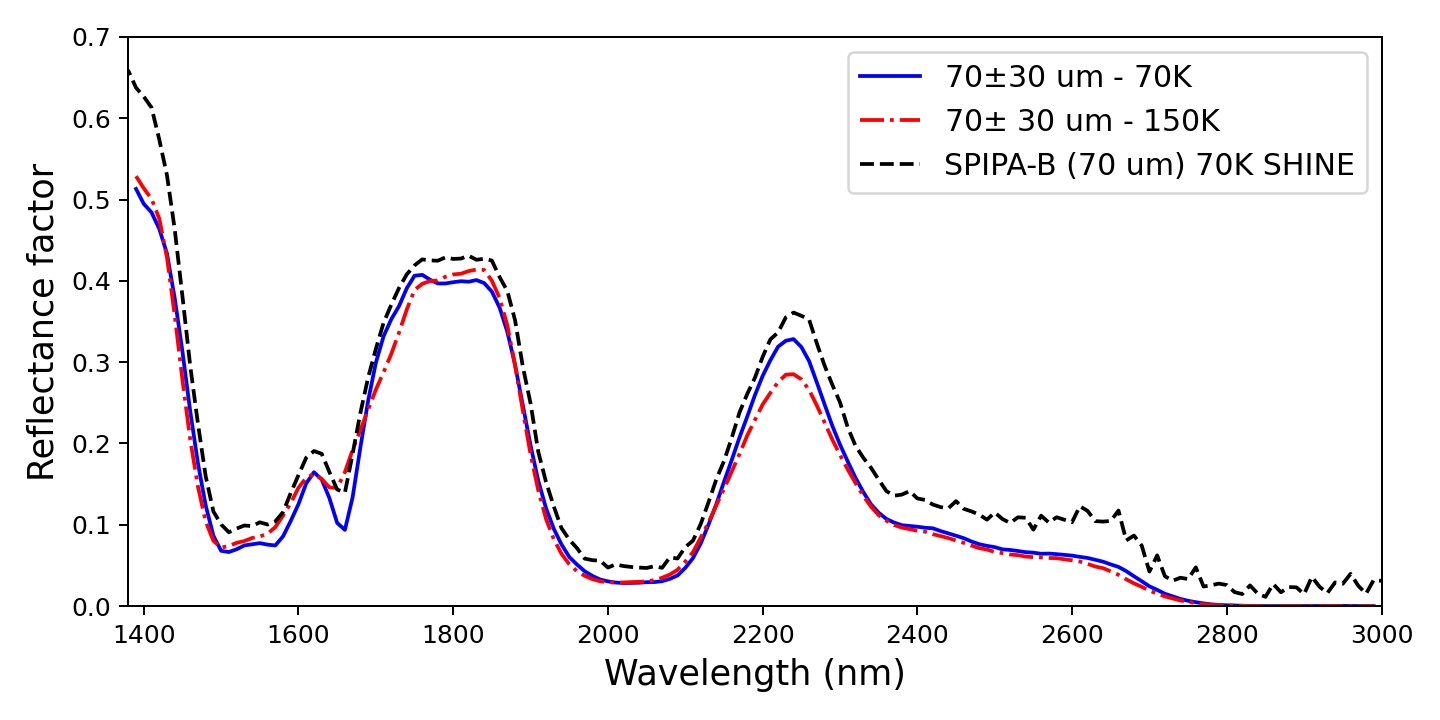

As a first test, we modelled a particulate ice sample composed of spherical grains with a diameter of 70±30 µm. The grains were packed to a volume fraction ρ=0.5 (see Figure 1). This closely resembles the laboratory analogue sample produced by flash-freezing droplets in liquid nitrogen as described by the SPIPA-B protocol. We present results including the energy deposition depth in function of the incidence angle, the bidirectional reflectance distribution function and the reflectance spectra of this and other modelled samples.

Conclusions

We developed a GPU-accelerated ray-tracing code that simulates the interaction of light with planetary regolith. The efficiency of the code allows the simulation of laboratory-sized samples for a large group of conditions. Within the GO regime, it enables the study of a wide range of observables and effects, including the simulation of bidirectional reflectance function and reflectance spectra, the hemispherical albedo in function of incidence angle, the energy deposition depth in function of incidence angle, the effect of grain size, shape and bonds, the impact of surface roughness on different size scales and the mixing of different compositions.

Figure 1: Two simulated reflectance spectra with 1’000’000 rays per wavelength. The incidence angle is 0°, the emission angle between 10-40°. The real and imaginary indices of refraction are from Mastrapa et al. 2008 (10.1016/j.icarus.2008.04.008). The sample consists of millions of spherical ice particles with a gaussian size distribution around 70 um that are packed to a volume fraction ρ=0.5. The simulation for the whole wavelengths range takes less than an hour on a single GPU. A laboratory reflectance spectrum of a SPIPA-B granular ice sample is shown in comparison.

Data reference for the laboratory spectrum:

Stephan, Katrin; Ciarniello, Mauro; Poch, Olivier; Haack, David; Raponi, Andrea (2019): Vis-NIR reflectance spectra of H2O ice with varying grain sizes (70-1060µm), shapes (spherical or irregular) and three mixtures, from 70 to 220 K. SSHADE/CSS (OSUG Data Center). Dataset/Spectral Data. https://doi.org/10.26302/SSHADE/EXPERIMENT_OP_20201223_001

How to cite: Ottersberg, R., Pommerol, A., and Thomas, N.: Modelling light scattering in icy planetary regolith using GPU accelerated ray-tracing, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1688, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1688, 2025.

Introduction

The next generation of lidar instruments will encompass the full waveform recording, allowing travel-time measurement of each emitted photon packet. This new information will allow finer characterization of planetary surface medium, either spaceborne, in-situ or in lab; for instance, the BepiColombo laser altimeter (BELA) (Thomas et al., 2021) will explore Mercury. We propose here a tool to simulate in-silico the travel-time inside the planetary medium and reconstruct the full waveform. It is a Monte-Carlo ray tracing algorithm called WARPE, for Waveform Analysis and Ray Profiling for Exploration (Barron et al, 2025).

Methods

We propose a Monte Carlo ray tracing approach based on the work from Farrell et al., 1992, Wang et al., 1995 and Gastellu-Etchegorry et al., 2016. Our model computes the position of the ray during its travel through the medium, including interactions at the interfaces. The main parameters are incidence (θ) and azimuthal angle (φ), the optical thickness (τ), the single scattering albedo (ω) the optical index (n,k) of the medium and the phase function (Henyey-Greenstein or isotropic). The efficient computation time of the model is guaranteed by ray batchs parallelization.

Validation

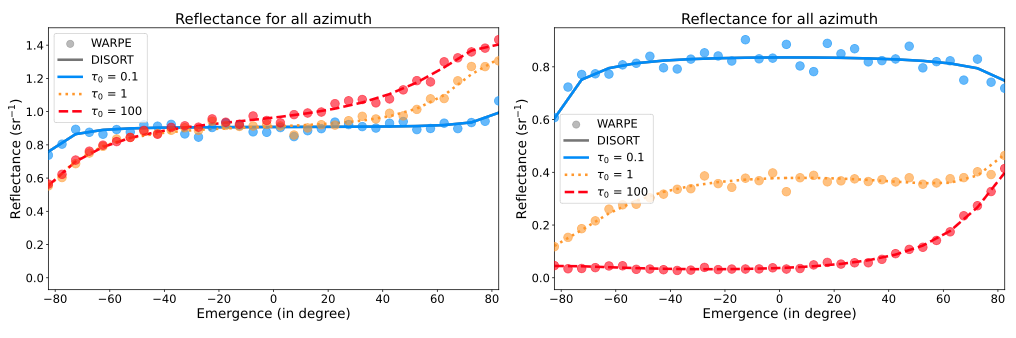

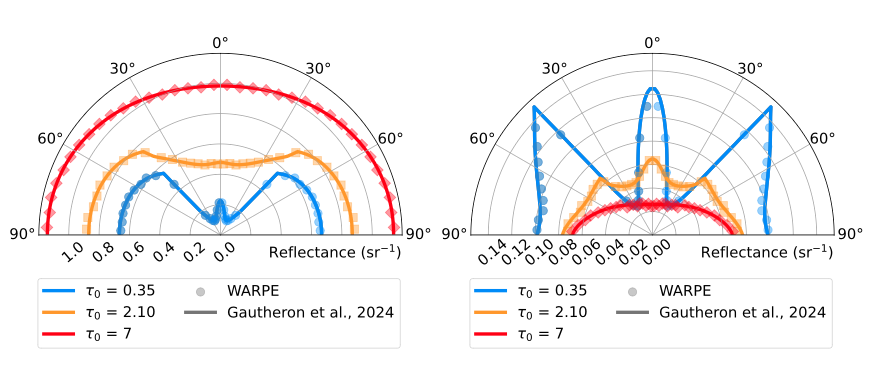

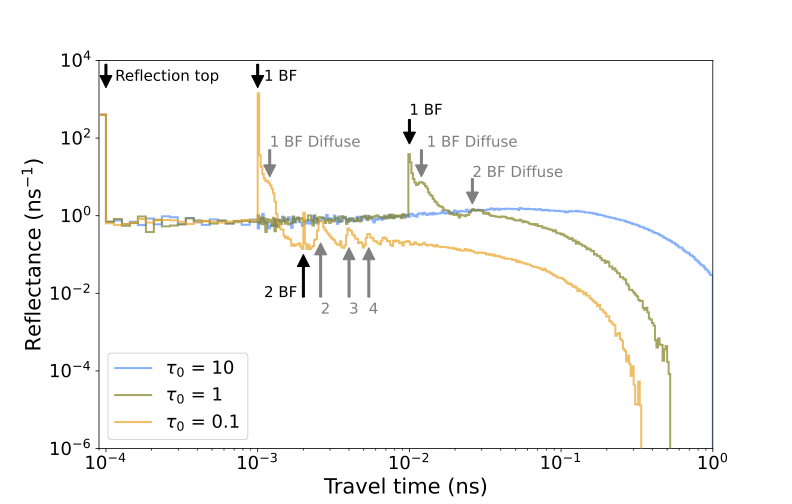

The validation of the model is a mandatory step to compute a consistent and physically correct simulation of the travel-time within a planetary surface. In the model, media can be either described as a semi-infinite granular layer or a homogeneous slab above a bedrock or regolith of albedo (A). The purpose here is to replicate the results from previous works such as Stamnes et al., 1988, Gautheron et al., 2024 and Kienle & Patterson 1997. We first computed the reflectance for a turbid medium with (figure 1) and without (figure 2) interfaces. We use the DISORT algorithm (Stamnes et al., 1988) and the model presented in Gautheron et al., 2024. Our simulations show a very good agreement, confirming the validity of WARPE for angular distribution. The Relative Root Mean Square Error (RRMSE) is ∼ 0.01 in most of cases, which is excellent and expected due to the stochastic nature of WARPE.

Figure 1: Reflectance of a turbid medium with WARPE (point) and DISORT (line) for θ = 50°. ω = 1, A = 0.9 (left), ω = 0.7, A = 0.9 (right). The diffusion is anisotropic following a 1-parameter Henyey-Greenstein phase function with g = 0.8.

Figure 2: Reflectance from WARPE (points) and from the Gautheron et al., 2024 model (lines) within the medium at the top interface, as a function of emergence for with ω = 1 on the left and ω = 0.7 on the right, n = 1.5. The diffusion is anisotropic and follows a 1-parameter Henyey-Greenstein phase function (with g = 0.8).

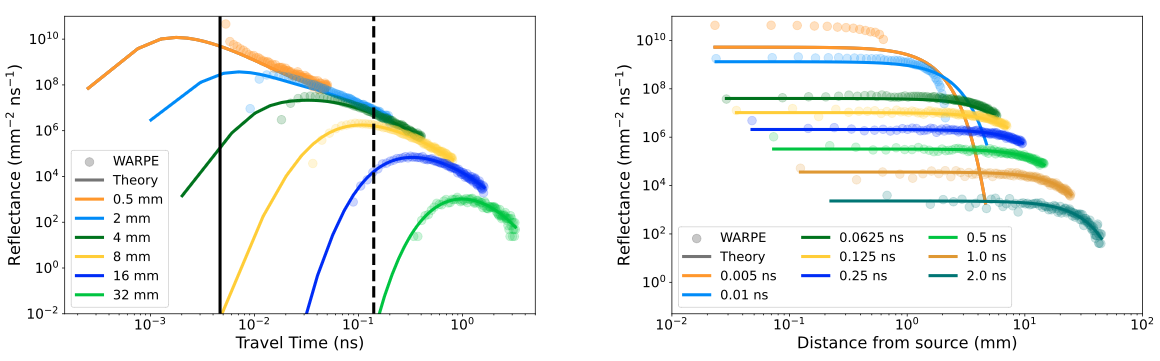

We propose then a method to compute the trajectory and travel-time of rays in the medium, to simulate the response of a waveform lidar. Knowing the speed of light in the medium and assuming its constancy following medium’s optical properties, we then evaluate the time travel in comparison with the analytical solution from Kienle & Patterson, 1997. Results in Figure 3 shows a very good agreement that validates our algorithm.

Figure 3: Reflectance in a compact medium from WARPE (point) and analytical model from Kienle & Patterson (1997) model (line); (left) as a function of travel-time at distance from the source; (right) as a function of distance from the source at different time. Parameters are τ = 60, n = 1.4 and k = 0, z0 = 0.995 mm and t0 = 4.67 ps. The diffusion is isotropic (g = 0), the approximation for the anisotropic diffusion being too imprecise in the Kienle analytical model. The full vertical line represents the travel-time at t0 = z0 /n to leave the medium in a straight path without interaction, when the source is at depth z0 . It is thus not physically possible that a travel-time shorter than this exists. Our model fulfills this condition, but the analytical solution does not. The dash vertical line represents the time from which WARPE and reference model reasonably agree (after ∼ 30t0 ).

Result

To illustrate the capabilities of WARPE, we simulate waveforms for different sets of parameters. We identified 4 main features: the top reflection corresponding to specular reflection, the back and forth direct represents rays unscattered in the medium but reflected 1/2/3… times in the bottom and top interfaces, the back and forth diffused represents the “pseudo-wave” of all scattered rays and finally the background scattering. Figure 4 shows the effect of the optical thickness and how the features are affected. We are now able to identify how the media properties will affect the response of a full waveform lidar.

Figure 4: effect of the optical depth on the travel-time. Parameters θ = 0°, ω = 1, A = 0., n = 1.5, rand a Henyey-Greenstein phase function with a scattering anisotropy of g = 0.8, scattering coefficient is 1, absorption coefficient is 0. The physical thickness is 0.1 (orange) 1 (green) 10 (blue) mm. The back and forth direct (BF) and the back and forth diffuse (BF Diffuse) features are more visible when the medium is optically thin. For thicker medium the main feature tends to be the background scattering.

Conclusion and perspectives

We propose a new approach to efficiently simulate the travel-time of photons inside a planetary surface with both granular and compact texture. We conducted several tests to validate the approach and one simulation in realistic conditions. In the future, we will adapt this tool to peculiar planetary science cases, such as the mercury regolith for BELA, or the icy surface for GALA.

References

Barron et al. (2025) under review Journal of Quantitative Spectropy and Radiative Transfer

Farrell et al. (1992) Medical Physics

Gastellu-Etchegorry et al. (2016) Remote Sensing of Environment

Gautheron et al. (2024) Optics Express

Kienle et al. (1997) Journal of the Optical Society of America

Stamnes et al. (1988) Applied Optics

Thomas et al. (2021) Space Science Reviews

Wang et al. (1995) Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine

How to cite: Barron, J., Schmidt, F., and Andrieu, F.: WARPE: A new tool to simulate radiative transfer and travel-time to characterize planetary surfaces , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-307, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-307, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

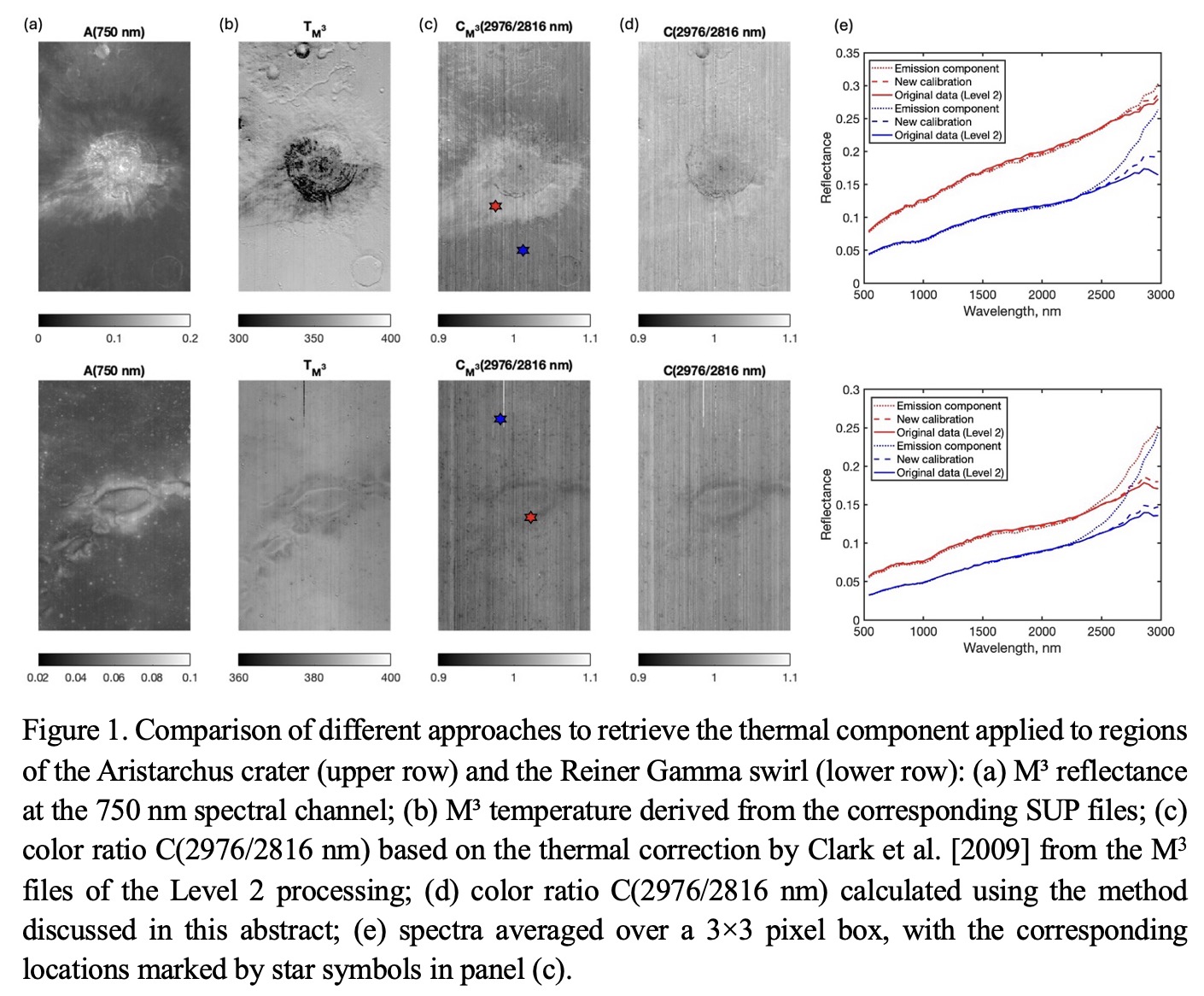

Introduction: Thermal emission appears in lunar reflectance spectra beyond ~2500 nm, where surface-emitted radiation becomes comparable to sunlight reflection [e.g., 1,2]. This thermal component distorts diagnostic absorption bands of minerals such as pyroxenes and spinel [e.g., 3] and can obscure spectral signatures of volatiles like hydroxyl and water (OH/H₂O). Several methods have been proposed to retrieve this component [e.g., 1,4–6]. Among them, the iterative procedure proposed by Clark et al. [4] is widely used and has been implemented in the Chandrayaan-1 M³ calibration pipeline [7]. The method assumes the lunar surface behaves as a gray body, with emissivity defined as 1 – R₀(λ), where R₀(λ) is the reflected solar fraction. However, R₀(λ) is geometry-dependent and not directly observed beyond 2500 nm, requiring a complex iterative approach to assess it with approximations before separating the thermal emission from the reflectance [4].

Method: Here, we explore an alternative approach for thermal emission removal from M³ data using a single-step subtraction of the thermal component [1,2]. Like previous methods, it is based on the graybody concept. However, it avoids empirical estimations of the reflected solar fraction by treating thermal emissivity in a different way. The first step is to define the forward model. The apparent albedo, obtained by dividing the measured radiance by the incident solar flux, can be expressed as follows:

Here, α, i, and e denote the phase, incidence, and emergence angles, with i and e depending on the local surface normal. Ar+e(λ) includes both reflected and emitted components; An(λ) is the reflectance at normal geometry, and F(α, i, e, λ) is the photometric function. Constants are LSun = 1.696×10¹¹ m, RSun = 6.96×10⁸ m, and C₂ = 1.44×10⁴ µm·K. Emissivity is defined as 1 − ε·An(λ), where ε·An(λ) is the hemispherical-directional albedo. The general expression for ε is (see Eq. 6.14 in [2])

where φ is the azimuthal angle. Finally, one can invert Eq. 1 with respect to An(λ) and obtain an expression for the normal albedo:

Data: To demonstrate the method, we applied it to M3 data from the Aristarchus crater (Frame ID: M3G20090612T060502) and the Reiner Gamma swirl (Frame ID: M3G20090613T032520), as shown in Fig. 1a. Due to the iterative nature of the original thermal correction [7], we began with level-1 data and performed solar normalization, thermal correction, and photometric correction to bring the data into the RELAB photometric system (30°, 0°, 30°). Whenever possible, we used original M3 calibration inputs, including the solar spectrum, digital terrain models, geometric angles, and the photometric function [7]. To isolate the effect of thermal correction, we retained the original surface temperature maps (Fig. 1b), although alternative temperature-estimation approaches also exist [e.g., 2,5]. For simplicity, we assume emissivity as 1 − An(λ), consistent with the original approach [4]. The factor ε = 1 follows from Eq. 2 if a Lambertian-like photometric function F(α, i, e, λ) = cos(e)cos(i) is used. This approximation neglects the subpixel-scale structure of the lunar surface, which will be addressed in future work. Lastly, we did not apply the thermal-polishing step from the original pipeline [7], as this correction multiplies the spectra by a coefficient close to one and generally has a negligible effect.

Results: Both frames were acquired at relatively small phase angles: 21.3° for the Aristarchus crater and 8° for Reiner Gamma, resulting in a notable thermal-emission component between 2700 and 2950 nm. The selected sites show significant reflectance differences, and the Aristarchus region also features strong temperature variations due to complex topography. This makes them suitable for testing the method by (1) mapping the color ratio C(2976/2816 nm) using both the original M3 reflectance data (Fig. 1c) and the proposed approach (Fig. 1d), and (2) comparing the spectra from selected locations (Fig. 1e).

As shown, the color ratio derived from the original M3 reflectance data generally correlates with albedo, except for several sites on the southern slope and the crater peak. In contrast, the ratio calculated using the proposed method appears smoother and nearly featureless. It shows similar values across bright ejecta, the moderately bright southern Aristarchus Plateau, and the darker surrounding mare basalts. The lower values observed at the crater walls, central peak, and nearby areas are more likely linked to surface immaturity than to compositional differences. Similar behavior is seen at various mare-highland boundaries across latitudes, although these cases are beyond the scope of this abstract.

Lunar swirls, high-albedo diffuse formations, are among the few features that consistently exhibit lower color-ratio values. In Fig. 1, the Reiner Gamma swirl serves as an example. Notably, the swirl’s reflectance remains significantly lower than that of the bright Aristarchus ejecta. Thus, while their higher albedo may account for slightly cooler surface temperatures, it does not fully explain the reduced color ratios. This effect may instead point to the swirls’ unique photometric or compositional properties, as suggested by previous studies [e.g., 8].

Conclusions and future work: A simplified single-step method for thermal emission removal from Chandrayaan-1 M³ data has been considered. The method avoids complex iterative calibration. Applied to the Aristarchus and Reiner Gamma regions, it produces smoother spectral color ratios that do not reveal clear correlation with the surface reflectance. Future work will refine emissivity modeling and temperature estimation using more sophisticated photometry. The method could also be applied to other hyperspectral datasets of airless Solar System bodies, such as the High-Resolution Volatiles and Minerals Moon Mapper (HVM3) onboard Lunar Trailblazer [9].

References:

[1] Y. Shkuratov, et al. PSS 59, 1326-1371 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2011.06.011

[2] Y. Shkuratov, G. Videen, V. Kaydash, Optics of the Moon. Elsevier (2025). https://doi.org/10.1016/C2018-0-03000-5

[3] Y. Surkov, et al. PSS 240, 105831 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2023.105831

[4] R. Clark, et al. JGR 116, E00G16. (2011) https://doi.org/10.1029/2010JE003751

[5] S. Li, R. Milliken. JGR Planets 121(10), 2081-2107 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JE005035

[6] J. Banfield, et al. 47th LPSC, LPI, Houston, USA, 1594 (2016).

[7] S. Lundeen, et al (2011) http://pds-imaging.jpl.nasa.gov/data/m3/CH1M3_0004 /DOCUMENT/DPSIS.PDF.

[8] D. Domingue, et al. PSJ 5, 161 (2024). https://doi.org/10.3847/PSJ/ad2179

[9] D. Thompson, et al. 51st LPSC, LPI, Houston, USA, 2052 (2020).

How to cite: Surkov, Y., Shkuratov, Y., Penttilä, A., Muinonen, K., Björn, V., and Videen, G.: Untangling Heat: Retrieving the thermal component from Chandrayaan-1 M³ spectra, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1000, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1000, 2025.

Motion-induced blur resulting from the high relative ground velocity between spacecraft and planetary bodies significantly deteriorates image quality, complicating detailed analyses of planetary surface features. Notable examples include Mars Express SRC images of Phobos, Viking Orbiter 2 VIS images of Deimos, and Rosetta OSIRIS images of comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. To mitigate this issue, we implemented an image restoration method based on modeling the motion-induced point-spread function (PSF) and employing Wiener deconvolution to reverse the blur effects.

Our method was applied specifically to Super Resolution Channel (SRC) images acquired by the Mars Express High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) [1], which achieved unprecedented resolutions (<1.0 m/pixel) of the Phobos surface during orbit 5851 (23 July 2008) and orbit 8974 (9 January 2011) [2]. Despite their superior ground-sampling distance, these images had previously not been extensively utilized due to significant noise artifacts ("pepper" pixels) and severe motion blur [3], hindering geological interpretations and high-precision photogrammetric product generation (e.g., Ernst et al., 2023 [4]).

Our processing pipeline begins with Level 3 SRC images in PDS format. Noise artifacts are conventionally reduced using a boxcar filter implemented through the powerful USGS ISIS "noisefilter" function. Metadata (StartTime, StopTime, ImageTime, exposure, pixel size, focal length, CCD center coordinates) are extracted from ISIS cubes using the USGS Ale software. Given the very short exposure times (approximately 14 ms for orbit 5851 images and 16 ms for orbit 8974 images), the target's apparent motion on the focal plane during exposure can be accurately approximated as linear, differentiating this case from longer-duration sinusoidal jitter motions. We generated a linear PSF by computing spacecraft boresight intersections with the Phobos surface from SPK, CK, and DSK kernels (Ernst et al. 2023 Phobos shape model v02 NoOffset, ~9 m precision) via SpiceyPy [5]'s subpnt function. Wiener deconvolution was subsequently applied, utilizing an empirically determined optimal signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of 16 dB, aligning closely with previous findings for SRC images (Oberst et al., 2006).

We successfully restored SRC images from orbit 5851 (h5851_0002_src3 to h5851_0004_src3; Figure 1) and orbit 8974 (h8974_0002_src3 to h8974_0008_src3; Figure 2), significantly reducing blur and enhancing geological feature visibility. Our pipeline establishes a robust and objective framework for future restoration and analysis of motion-blurred planetary imagery.

References

1. Neukum, G.; Jaumann, R. HRSC: The High Resolution Stereo Camera of Mars Express. In Mars Express: The Scientific Payload; ESA: 2004; Volume SP-1240, pp. 17-35.

2. Witasse, O.; Duxbury, T.; Chicarro, A.; Altobelli, N.; Andert, T.; Aronica, A.; Barabash, S.; Bertaux, J.L.; Bibring, J.P.; Cardesin-Moinelo, A.; et al. Mars Express investigations of Phobos and Deimos. Planetary and Space Science 2014, 102, 18-34, doi:10.1016/j.pss.2013.08.002.

3. Oberst, J.; Schwarz, G.; Behnke, T.; Hoffmann, H.; Matz, K.D.; Flohrer, J.; Hirsch, H.; Roatsch, T.; Scholten, F.; Hauber, E.; et al. The imaging performance of the SRC on Mars Express. Planetary and Space Science 2008, 56, 473-491, doi:10.1016/j.pss.2007.09.009.

4. Ernst, C.M.; Daly, R.T.; Gaskell, R.W.; Barnouin, O.S.; Nair, H.; Hyatt, B.A.; Al Asad, M.M.; Hoch, K.K.W. High-resolution shape models of Phobos and Deimos from stereophotoclinometry. Earth, Planets and Space 2023, 75, 103, doi:10.1186/s40623-023-01814-7.

5. Annex, A.M.; Pearson, B.; Seignovert, B.; Carcich, B.T.; Eichhorn, H.; Mapel, J.A.; Von Forstner, J.L.F.; McAuliffe, J.; Del Rio, J.D.; Berry, K.L. SpiceyPy: a Pythonic Wrapper for the SPICE Toolkit. Journal of Open Source Software 2020, 5, 2050, doi:10.21105/joss.02050.

Figures

Figure 1 SRC images of orbit 5851 before (top) and after (bottom) restoration

Figure 2 SRC images of orbit 8974 before (top) and after (bottom) restoration

How to cite: Hemmi, R. and Kikuchi, H.: Restoring high-speed motion blur in spacecraft imagery: Enhanced views of Mars' moon Phobos, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-193, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-193, 2025.

Introduction

This study aims to improve the recognizability of objects (e.g., craters) in imaging data of the surfaces of celestial bodies acquired by JANUS (Jovis, Amorum ac Natorum Undique Scrutator), a two-dimensional spectral imaging camera on the JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE)1,2), a joint mission of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

JUICE was launched on April 14, 2023, and is scheduled to reach the Jupiter system in 2031. After multiple flybys of Jupiter, Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto until November 2034, it will perform an orbital observation of Ganymede. The mission is planned to conclude with a collision into Ganymede in 2035. The main scientific targets of JANUS are the geological and topographical features of these icy satellites, as well as phenomena such as lightning occurring in Jupiter’s upper atmosphere. Thus, the imaging data from JANUS covers a wide range of topics. And of course, its higher resolution data offers more advantages in planetary science studies. For example, in crater chronology, higher resolution allows for the identification of more craters, which ultimately enables more accurate model age determinations. Detailed crater morphology also contributes to understanding the impact process, timing, and the physical constraints of the impacted celestial body’s surface. However, due to constraints such as the spacecraft's altitude, the total amount of internal data storage, and the transmission data rate to the Earth, the resolution of the data acquired by JANUS will be strictly limited. This study, therefore, explores the possibility of improving the object recognizability by increasing the resolution in a pseudo manner for JANUS imaging data using frame overlap. The data from the August 2024 Moon and Earth flybys, which included overlapping frames obtained by JANUS, will be used for this experiment. The lunar imaging data, obtained by Japan’s SELENE e.g. 3) and the U.S. LRO e.g. 4) missions at high resolutions, will be compared to evaluate the potential for enhancing the JANUS data.

Methodology

JANUS is a two-dimensional imaging camera with 2000 x 1504 pixels (along track x across track) and a field of view of 1.72° x 1.29°1,2). The instantaneous field of view (IFOV) of each pixel is 15 μrad, which corresponds to 7.5 m/pixel when observed from an altitude of 500 km (e.g. during the Ganymede flyby). Depending on the operation, JANUS images can be captured in succession to create frame overlap. For this study, we used the overlapping frame data acquired during the JUICE Moon flyby in August 20241,2).

The image enhancement process follows the steps outlined below (see Fig. 1):

1) Sub-Pixel Interpolation: The first step is sub-pixel interpolation to enhance image resolution in a pseudo manner.

2) Image Registration: Image registration is performed using template matching at a sub-pixel level, where the difference in brightness values is minimized.

3) Stacking and Normalization: The aligned overlapping images are stacked, and the radiance values are averaged to normalize the result.

The resulting "processed image" will be compared with high-resolution images from SELENE and LRO to assess the degree of enhancement achieved.

Sub-pixel interpolation will be performed using the Awesome Sindones (AS) processing. This method aims to reduce or remove mosaic artifacts that occur during image enlargement, and is expected to improve the recognizability of features such as shape and texture that are difficult to identify in the original image.

The key features of the AS processing are as follows:

- It is a quick and easy processing.

- It is reversible, meaning the original image can be reconstructed.

- It can significantly reduce mosaic artifacts with repeated applications.

- It enhances edges such as object contours.

Among these features, the reversibility of AS processing is particularly important because it allows other researchers to convert the AS processed data back to the original images and apply different preprocessing methods separately. This is not possible with traditional interpolation methods such as bilinear or cubic convolution.

Results

We present the results of our attempt to process panchromatic data (footprints #50-#60; see Fig. 2) obtained during the JANUS lunar flyby and improve the recognizability of lunar craters. These data were taken on the lunar surface at approximately 9°S and 66°E. Sample images (footprints #61-#63, see Fig. 3) are shown in the figure (filter: FPAN, pixel scale: 18.7-18.9 m/pixel). Comparing the original data with the processed images, we can see that the edges of some craters are enhanced in the processed images, making the details more clearly visible (Fig. 4). Furthermore, comparing the results of the AS method with other interpolation methods (bilinear and cubic convolution methods), we can see that the AS processing enhances edges more effectively, making craters easier to identify (Fig. 5).

Conclusion