- 1School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, UK (s.lock@bristol.ac.uk)

- 2School of Physics, University of Bristol, UK

- 3School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University, USA

- 4Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California Davis, USA

- 5Now at California Air Resources Board, USA

- 6Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, USA

Introduction:

How the parent bodies of chondritic meteorites, and the chondrules they host, formed is one of the most hotly debated questions in planetary sciences. The curious properties of chondrules have presented significant challenges to theoretical models that have tried to understand their formation and there is currently no consensus on the ability of the various proposed mechanisms to form chondrules consistent with the physicochemical constraints.

Here, we present the newly proposed IVANS (Impact Vapor Plumes and Nebula Shock) model for chondrule and chondrite formation (Stewart et al. 2025) and discuss how particles are size sorted and collected into chondritic mixtures (Lock et al.).

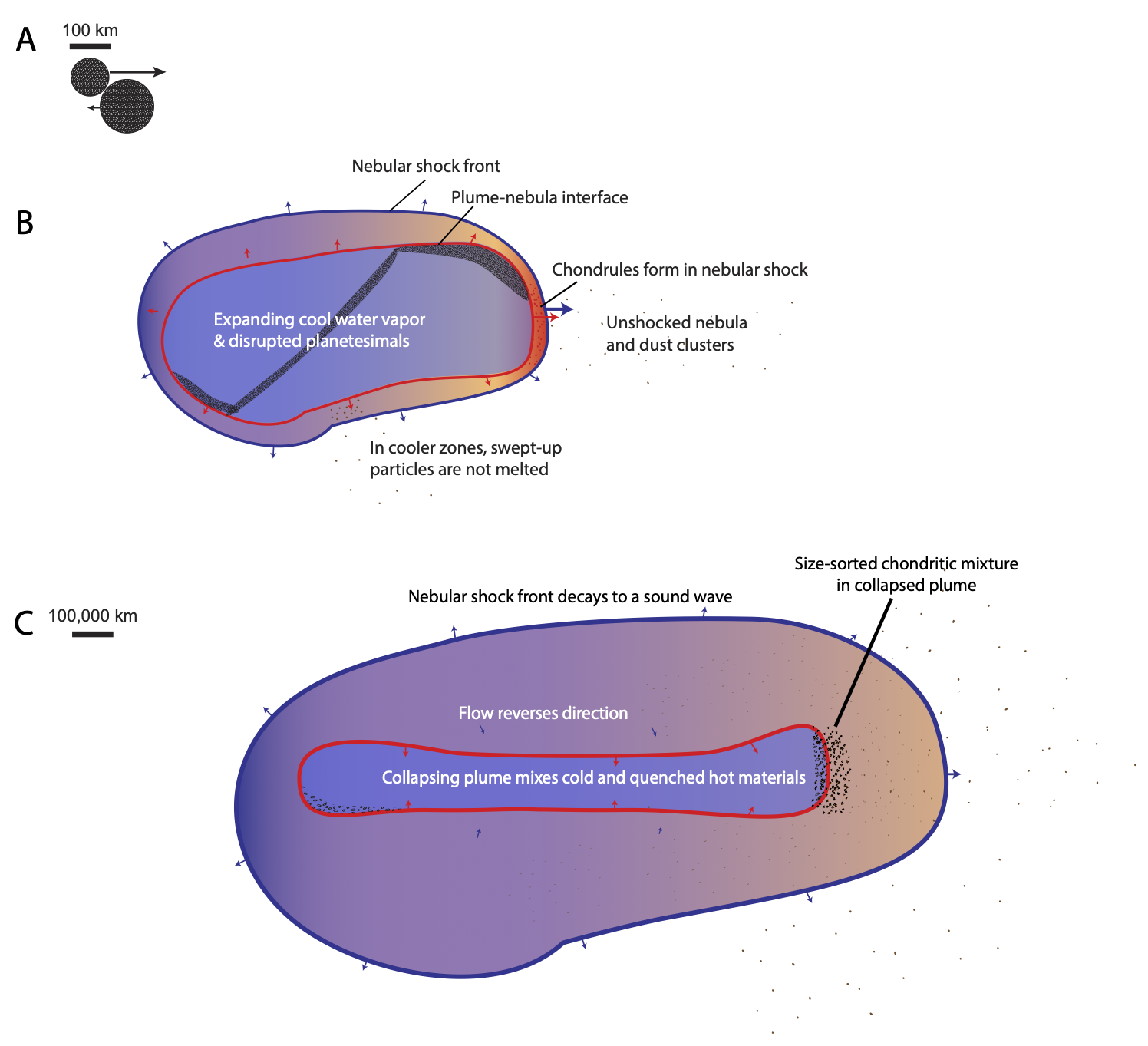

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the hydrodynamics of impact vapor plumes and nebular shocks (Stewart et al. 2025).

The Impact Vapor Plumes and Nebula Shock (IVANS) model:

A schematic of the IVANS model (Stewart et al. 2025) is shown in Figure 1. The IVANS model is based on vaporizing collisions between planetesimals composed of dust and ice in the presence of the nebular gas. Above about 1 km/s, the impact velocity is great enough to drive disruption and vaporization of a fraction of the colliding bodies (Figure 1A). Such collisions are frequent during planet formation before gas disk dispersal, particularly in epochs in which giant planets were growing rapidly and/or migrating (Carter & Stewart 2020). Each impact generates a cloud of cooling water vapor from the planetesimals which expands supersonically (inner blue region in Figure 1B), driving a warmer shock wave into the solar nebula (outer ring with warm colors). The elongated expanding shell of shocked nebula is hotter in the principal impact direction and cooler in the opposite and lateral dimensions (indicated by the color gradient). Portions of the shocked nebula are warm enough to melt free-floating nebular dust and form chondrules. Expansion of the vapor plume eventually leads to a pressure low in the solar nebula and subsequent hydrodynamic reversal in the flow field (Figure 1C). The nebular gas, dust, and chondrules flow into the low pressure region, mixing materials that were processed in different regions. The collapsed mixture has the characteristics observed in chondritic mixtures: quenched chondrules mixed with dust and ice. The mixed region is orders of magnitude larger in scale than the original planetesimals and the timescale of the collapse is order 10s hours.

Breakup and coupling of particles in the IVANS model:

We calculated the drag force on individual dust grains and aggregates to determine which size particles can couple to the gas in impact-driven nebular shocks. The nebular shock and the vapor plume-nebular interface were both treated as step changes in gas velocity. The acceleration of particles were then calculated using drag formulations for the relevant regime (Brown & Lawler 2003; Probstein 1969). The stability of particles to shear was assessed using experimentally-determined criteria (Theofanous 2011), or comparison between the drag force and surface tension (liquid droplets) or tensile strength (aggregates).

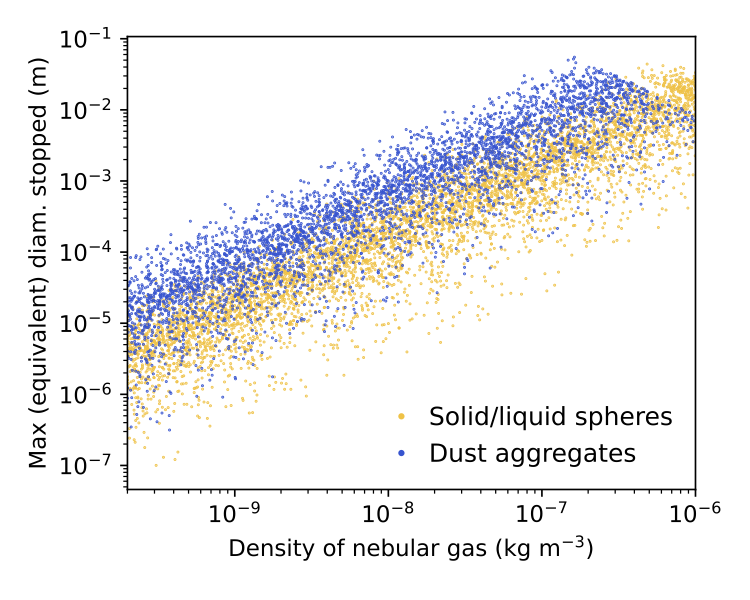

Using a Monte-Carlo approach, we varied the densities of the nebular gas, plume gas, nebular shock velocity, nebular shock length scale, and plume length scale over a large range. We found that the dominant parameter that determines the maximum size particle that is coupled to the nebular shock or plume front is the density of the nebular gas (Figure 2). Larger particles simply pass through the shock and are then not collected in the collapsing system. In this sense, the system acts as a ‘reverse-sieve’.

Under the conditions of impact-driven nebular shocks, the maximum size of coupled particles agrees well with the maximum size range of chondrules for the plausible range of nebular gas densities (chondrules typically span 0.1 to a few mm in size; Metzler, 2018). Different chondrite groups have different maxima and mean size chondrules (Jones 2012), which is interpreted to mean that they formed in distinct nebular environments. Within the framework of the IVANS model, the variation in the nebula pressures/densities at the time/place the chondrule forming impact occurred is responsible for the difference in chondrule sizes.

Figure 2: The maximum sizes of chondrules collected in the IVANS model are a strong function of the nebular gas density. Points are the maximum size of particles stopped in the nebular shock for each of our Monte-Carlo simulations for both dust grains or (partially) molten droplets (orange) and dust aggregates (blue). The size of aggregates is given as the equivalent size if the aggregate melted to form a chondrule.

Conclusions:

We find that processing of material by vaporizing collisions in the solar nebula produces a size-sorted assembly of melted silicates with the first-order physical and chemical properties of chondrules. The IVANS model therefore provides a promising new explanation for the origin of chondrules and chondrites.

In the IVANS model there is a mechanistic link between vaporizing collisions and chondrites. Chondrites are not only precious time capsules of primitive nebular materials but also key records of the wider dynamics of planet formation. The different degrees of thermal processing through nebular shocks experienced by different meteorite groups reflects the collisional histories in different locations and at different times in the solar nebula (Carter & Stewart 2020). The chondritic record can therefore place constraints on the formation and migration of the gas giants and so the dynamics of giant and terrestrial planet formation.

References:

Brown PP, Lawler DF. 2003. J. Environ. Eng. 129(3):222–31

Carter PJ, Stewart ST. 2020. Planet. Sci. J. 1(2):45

Jones RH. 2012. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 47(7):1176–90

Lock SJ, et al. In prep.

Metzler K. 2018. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 53(7):1489–99

Probstein RF. 1969. In Problems of Hydrodynamics and Continuum Mechanics, pp. 568–83.

Stewart ST, et al. In press. Planet. Sci. J. doi: 10.3847/PSJ/adbe71. arxiv: 2503.05636

Theofanous TG. 2011. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 43(1):661–90

How to cite: Lock, S., Carter, P., Stewart, S., Davies, E., Petaev, M., and Jacobsen, S.: Coupling and breakup of particles in the impact vapor and nebular shocks (IVANS) model of chondrule formation, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1705, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1705, 2025.