- German Aerospace Centre (DLR), Berlin, Germany (santangelosabatino@gmail.com)

Introduction: The Moon has been suggested to have a highly asymmetric volcanic history, with at least three times more volcanic activity recorded on the nearside with respect to the farside [1]. One possible explanation to the asymmetry has been suggested to be the asymmetric distribution of subsurface Heat Producing Elements (HPE, i.e. Th, U, and K) [2]. However, the timeline and nature of a potential redistribution of HPE, during or after the lunar magma ocean (LMO) solidification, remains highly debated [3].

Here, we investigate the lateral distribution and concentration of HPE, testing various extents and enrichments of a putative KREEP-rich anomaly formed during or after LMO crystallization [3]. Modeled present-day surface heat flux is compared to observations to identify best-fit models of lunar interior.

Methods: We model the thermal evolution of the Moon in a 3D spherical shell geometry, using the geodynamic code Gaia [4]. The code solves the conservation equations of mass, linear momentum and thermal energy, assuming a homogeneous mantle with purely Newtonian rheology and negligible inertia.

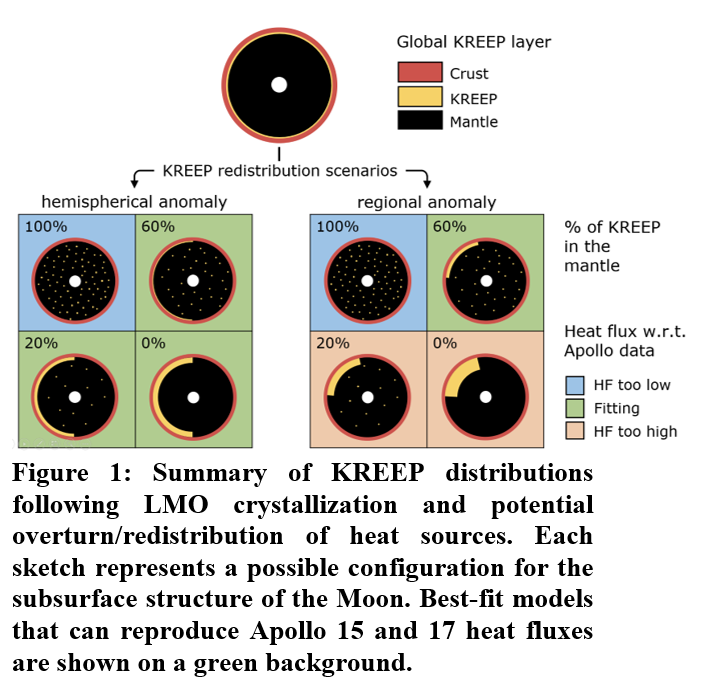

First, we use a simplified model setup consisting of a thin KREEP unit squeezed between a homogeneous mantle and a 39-km-thick crust. Using this setup, the lateral extent of the KREEP layer is varied between global, hemispherical (i.e. nearside), regional (i.e., 1300 km radius assuming circular geometry), and completely absent (Fig. 1).

Additionally, the concentration of HPE in the layer is varied to simulate different scenarios from a complete overturn and KREEP remixing (100% of KREEP in the mantle, no KREEP layer) to a perfectly efficient KREEP concentration underneath the nearside (0% of KREEP in the mantle, Fig. 1). For all scenarios, we compare the predicted heat flux to the Apollo measurements and discard inconsistent models.

Next, we use a more sophisticated model, similar to [5], to investigate the local heat flux variability at the Apollo 15 and 17 landing sites, and in regions with remote-sensing low heat flux estimates [6]. This second model employs a laterally variable crustal thickness [7], and a laterally variable KREEP layer thickness that considers basin excavation.

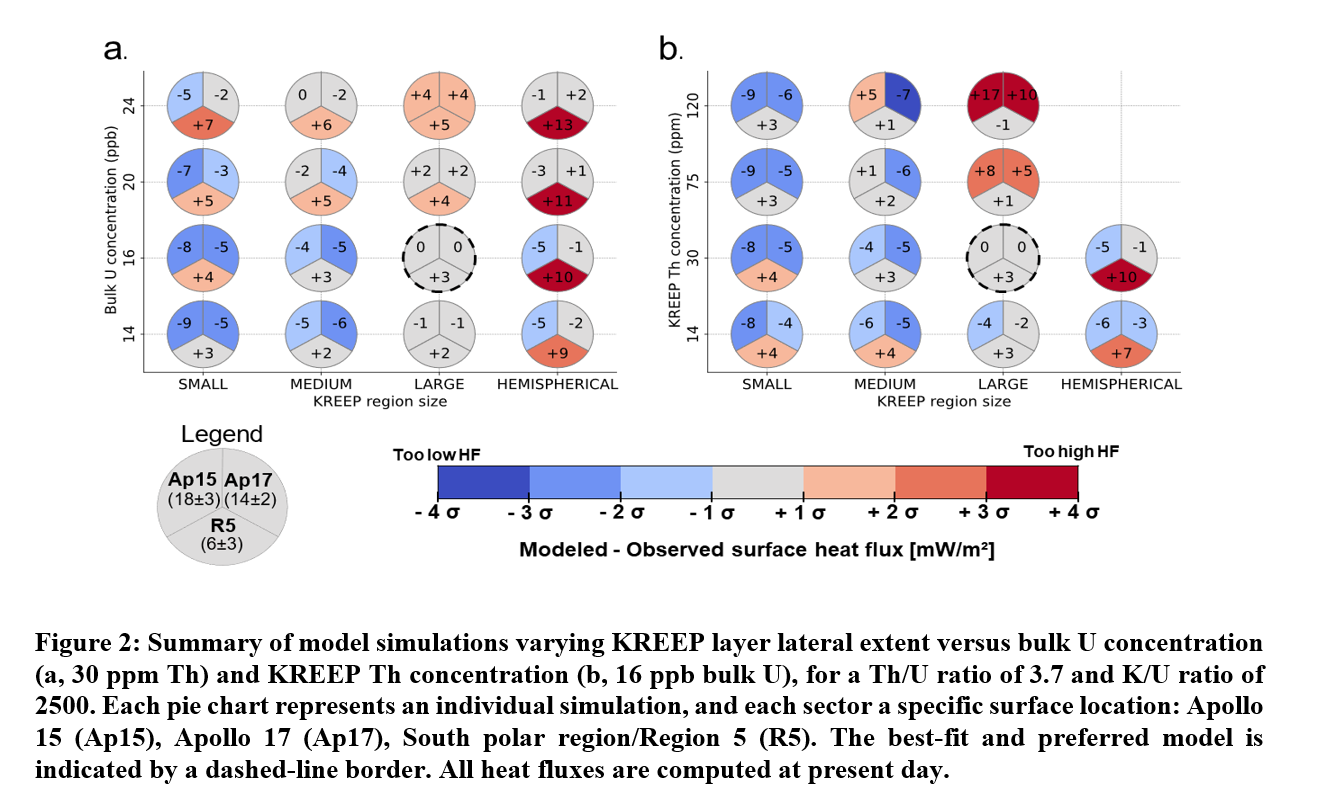

In this second setup, we vary the lateral extent of the KREEP anomaly relative to the observed heat flux data. First, we assume all three locations of interest (Apollo 15 and 17 landing sites, and nearside south polar region) to be underlain by a hemispherical KREEP layer (Fig. 2). Additional models include a KREEP layer only beneath the two Apollo sites (large KREEP size model), only beneath Apollo 15 (medium KREEP size), and far from all three locations (small KREEP size). For each model configuration, we also vary the HPE concentration of the crust and KREEP layer, and the lunar bulk U abundance, and we select models that can reproduce currently observed lunar heat flux values (Fig. 2).

Results and discussion:

Constant crustal thickness setup. Using the simpler model setup (constant crustal thickness) we are able to exclude end-member KREEP distribution scenarios (Fig. 1). The scenarios of global KREEP layer and complete KREEP overturn/remixing (topmost sketch and blue tiles in Fig. 1, respectively) cannot produce heat flux values as high as Apollo 15, assuming Earth-like HPE abundances [8]. For a regional KREEP layer (~1300 km radius), we find that at least 60% of KREEP material is required to be remixed in the mantle to match Apollo 15 and 17 heat flux. Conversely, a hemispherical KREEP layer requires <60% of KREEP to be mixed in the mantle, in order to reach heat fluxes as high as Apollo 15 (Fig. 1).

Therefore, our results suggest that some degree of HPE sequestering on the nearside is likely, but it may not have been an efficient process. Up to 60-80% of KREEP material from magma ocean crystallization could have remained well-mixed in the mantle after overturn.

Variable crustal thickness setup. Using the more complex model setup, we find that surface heat flux at all locations increases with increasing bulk HPE (Fig. 2a). Increasing the KREEP HPE concentration increases the surface heat flux within the KREEP region and decreases it elsewhere (Fig. 2b), with the global surface average remaining constant.

If the remote-sensing estimate of a measurably lower heat flux in the south polar region is considered accurate [6], then our models with variable crust and KREEP thickness show that only a large, low-HPE-enriched KREEP beneath the Apollo 15 & 17 landing sites is able to reproduce the observation (~1600 km radius, 30 ppm Th concentration and 16-20 ppm bulk U). However, if the south polar estimate is considered inaccurate, we find consistent scenarios also for a hemispherical or medium KREEP (~1200 km radius), with south polar heat flux being comparable to the surface average (12-14 mW/m2).

The upcoming measurement by the LISTER instrument onboard Blue Ghost lander [9] will provide a heat flux value located sufficiently far from Oceanus Procellarum. Including this value in our model will allow us to put strong constraints on KREEP size and enrichment, along with bulk U concentration.

Outlook:

In future steps we will compute seismic velocities associated with our modeled temperatures. Similar to [10], we will combine our 3D thermal evolution models with ray tracing calculations using the TTBOX software package [11]. This will allow us to compare our results with the Apollo seismic measurements [12]. As a validation step, we will additionally test the feedback effect between the 3D temperature field predicted in our global models and crustal thickness inversions. In particular, we will input the temperature-induced density variations produced by our models in the crustal thickness inversion models in [7], and iteratively update our models to ensure that the crustal thickness estimates do not diverge due to the effect of temperature anomalies.

References: [1] Broquet and Andrews-Hanna (2024). [2] Laneuville et al. (2013). [3] Moriarty et al. (2021). [4] Hüttig et al. (2013). [5] Plesa et al. (2016). [6] Wei et al. (2023). [7] Broquet and Andrews-Hanna (2023). [8] Taylor and Wieczorek (2014). [9] Nagihara et al. (2023). [10] Plesa et al. (2021). [11] Knapmeyer (2004). [12] Nunn et al. (2020).

How to cite: Santangelo, S., Plesa, A.-C., Broquet, A., Breuer, D., and Grott, M.: Unveiling the subsurface extent of the lunar KREEP unit from geodynamic modeling., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1728, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1728, 2025.