- 1Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, London, UK

- 2Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA

- 3Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, USA

Introduction

Crater morphology is widely used to constrain target properties [1]. New investigations reveal ejecta spatial distributions as yet another promising subsurface probe [2,3]. In contrast to natural impacts, hypervelocity impacts of mission hardware allow us to eliminate uncertainty on impact conditions (projectile type, velocity, impact angle) and use impact sites to put tighter constraints on target properties.

During Mars 2020 entry, the cruise stage was detached from the entry vehicle (EV) carrying the Perseverance rover. Soon after, the EV ejected two cruise ballast mass devices (CBMD), 77 kg each, made of tungsten and unlikely to have broken up during entry [4]. The cruise stage must have fragmented into at least 3 pieces of uncertain characteristics because in total 5 new co-located craters were identified (this abstract), leading to uncertainty on which craters resulted from CBMDs. Here, we a) identify CBMD craters, and b) use them to investigate target properties of the area roughly 70 km to the north-west from Jezero crater.

Methods

The Program to Optimize Simulated Trajectories II (POST2), which is the flight dynamics tool used by the Mars 2020 team, predicted the fate of various pieces of hardware, including CBMDs [5]. We use their pre-flight landing ellipses, and find coordinates of 5 craters after precisely georeferencing image data [see 6]. We obtain their locations as follows: we 1) use HRSC products orthorectified to MOLA (a base), 2) register CTX images to that base, 3) register a HiRISE image to CTX. A pre-impact HiRISE image exists only for CMBD-a, -c and -e (Fig. 1), hence we measure ejecta radii only for those craters, and build up on the procedure from [7]: 1) we georeference pre- and post-impact HiRISE images, 2) subtract them, 3) map the residual, 4) sample the edge of the polygon with equidistant points, 5) measure distances between these points and crater centers (Fig. 2). Impact sites are analyzed in QGIS. In order to estimate target properties, we use scaling relations from [8].

Preliminary results

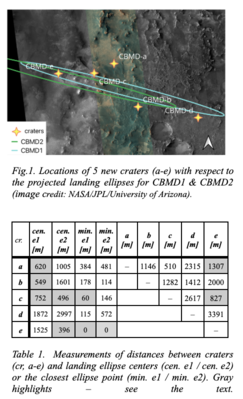

Location. Figure 1 displays the locations of 5 craters (marked as CBMDa-e). The outcome of the pre-flight simulations of trajectories for two cruise ballast mass devices, CBMD1 and CBMD2, are also shown as 99 percentile landing ellipses. In order to compare these two results, we calculated distances between a) all craters, b) craters and ellipse centers, c) shortest distances to the ellipses. These are reported in Table 1.

Crater CBMD-e falls within the landing ellipse of both CMBD2 and CMBD1 (but is closest to the center of CBMD2). The shortest distances to the center of the ellipse of CBMD1 are for craters CMBD-b, -a and -c, respectively, but only CBMD-c is located within 100 m from the landing ellipses. If we assume that CBMD-e is one of the craters formed by either of the ballast masses, we can use its distances to other craters as another constraint. For example, both CBMD-a and -c match the distance between the two centers of the ellipses (1141 m) to within the approximate width of each ellipse. Putting these arguments together (gray cell highlights in Table 1), we conclude that craters CBMD-c and CBMD-e are the most likely matches for the impacts of the original cruise ballast masses of Mars 2020.

Impact site characteristics. Table 2 reports the measurements of crater diameters. Craters CBMD-c and CBMD-e are nearly identical in diameter, which would be expected if two identical projectiles impacted the same target with identical velocities and impact angles. We also analyzed their ejecta radii and median absolute deviation as measures of asymmetries [7] (Table 2, Figure 2) to assess the impact sites similarity. However, ejecta patterns are not identical, possibly due to different topography.

Target properties. Preliminary calculations with pi scaling for sand or cohesive soil [8] place the strength parameter in the scaling relationship in the range 50-200 kPa, depending on the vertical component of the impact velocity, which is constrained to within a factor of two. More detailed results that follow from impact simulations are underway.

Preliminary conclusions

The fragmented cruise stage complicated the identification of craters excavated by ballast masses. We present several arguments that enabled us to distinguish CBMD craters from those made by cruise stage fragments. This advancement opens up a possibility to better constrain the local subsurface rheology. We will present a more detailed analysis of target properties at the meeting, including simulations with iSALE shock physics code [9] which explore complex target structures appropriate for the geologic settings shaped by fluvial processes.

References: [1] Prieur et al. (2018), 10.1029/2017JE005463 [2] Sokołowska et al. (2024), 10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116150 [3] Sokołowska et al. (2025), 10.1029/2024JE008561 [4] Nelessen et al. (2019), 10.1109/AERO.2019.8742167 [5] Way et al. (2021), 10.2514/6.2022-0421 [6] Kirk et al. (2021), 10.3390/rs13173511 [7] Gao & Sokołowska LPSC 2025, Abst.#2692 [8] Housen & Holsapple (2011) Icarus, 211, 1, 856-875. [9] Wünnemann et al. 2006. Icarus 180: 514–527.

Acknowledgements: This work is funded by a UKRI Horizon Europe Guarantee EP/Z003180/1. Special thanks to D. Way, B. Fernando and A. Chen for useful discussions.

How to cite: Sokolowska, A., Daubar, I., Collins, G., and Calef, F.: Solving the puzzle of too many craters from hardware impacts of Mars 2020, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1780, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1780, 2025.