- 1Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 2ARTORG Center for Biomedical Engineering Research, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 3Space Research & Planetary Sciences, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

Scientific Rationale:

Life on Earth exhibits a fundamental molecular dissymmetry arising from homochirality – the exclusive use of one enantiomer of chiral molecules in biochemistry. This universal trait of biogenic macromolecules (proteins, DNA, most pigments) is a unique characteristic of life (Cahn et al.,1956; Blackmond,2010). For example, the backbone of terrestrial DNA is composed of only right-handed (D) sugars, and proteins consist solely of left-handed (L) amino acids. Incorporating both enantiomers (a racemic mixture) into biopolymers would disrupt the formation of stable, functional structures, so life’s chemistry has evolved to be strictly single-handed.

Chirality’s Interaction with Light:

A direct consequence of molecular homochirality is that living matter interacts uniquely with electromagnetic waves. As Louis Pasteur already discovered in 1848, “living matter” can rotate the plane of linearly polarized light (Pasteur,1848). Much later, circular dichroism, i.e. the differential absorption of left- vs. right-handed circularly polarized light, was observed. This means that at specific wavelengths, biomolecules may preferentially absorb one circular polarization state over the other, imparting a net circular polarization to transmitted or reflected light (Wald,1957; Velluz et al.,1965).

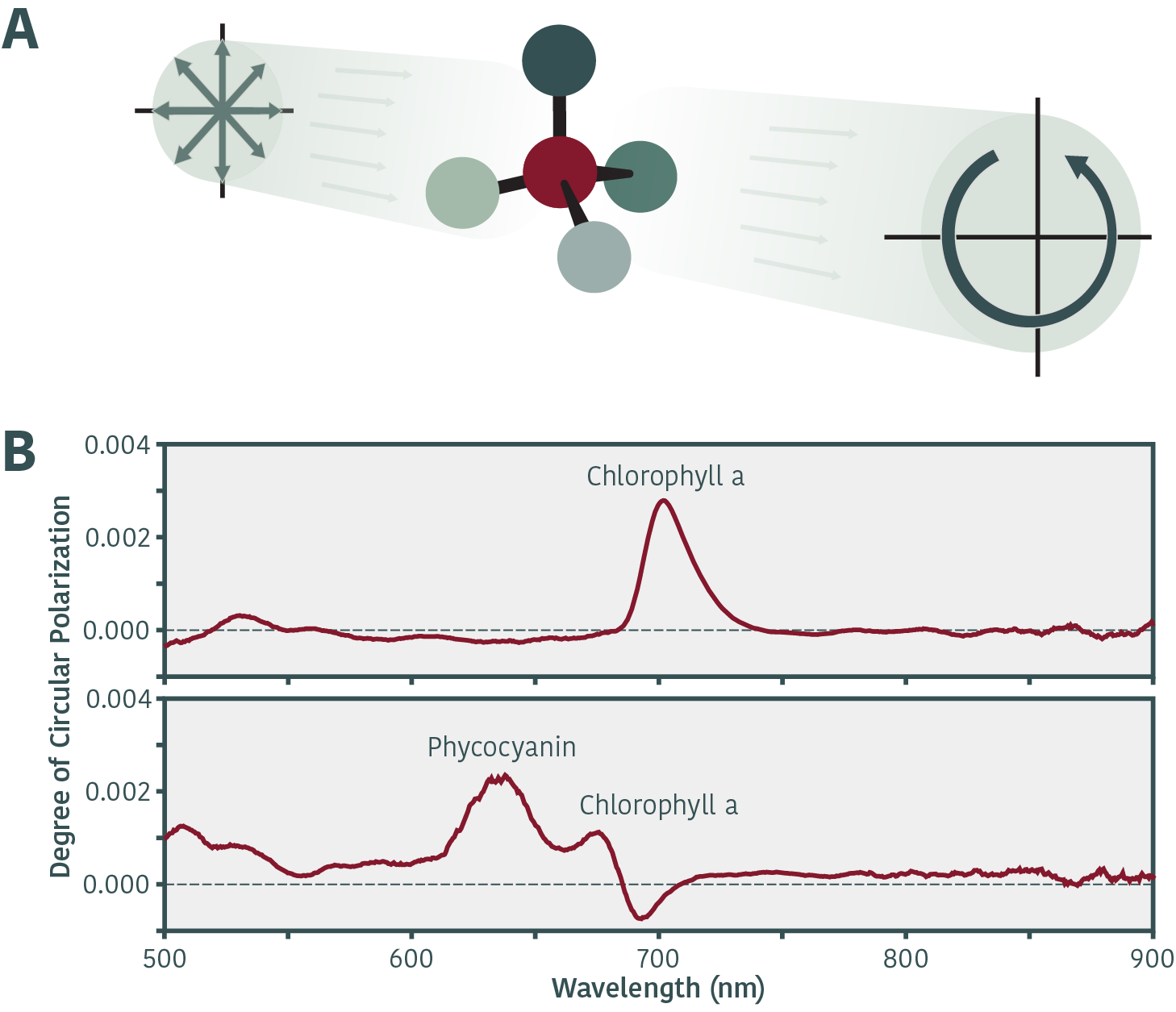

Fig.1: A) Illustration of circular polarizance. B) Example for circular polarization signals of a leaf in reflectance (upper panel) and cyanobacteria in transmittance (lower panel).

Circular Polarization as a Biosignature:

Following studies have revealed that even when initially unpolarized light (such as sunlight or starlight) is scattered from a surface containing chiral biopigments, it can acquire a faint but distinct circular polarization signature (Pospergelis,1969; Wolstencroft,1974; see Fig.1A). Crucially, the spectral pattern of this induced circular polarization correlates with the absorption bands of specific biological molecules: peaks in the degree of circular polarization coincide with wavelengths where pigments absorb, providing a fingerprint of life’s molecular dissymmetry (Kemp et al.,1971; Swedlund et al.,1972; Sparks et al.,2005; Patty et al.,2019; see Fig.1B). Importantly, circular polarization biosignatures have no known abiotic false positives. Additionally, because this effect does not require a pre-polarized light source (only an initially unpolarized illumination is needed), it is highly advantageous for remote sensing of life on other worlds (Kemp et al.,1987; Wolstencroft et al.,2004).

Observational Evidence:

Spectropolarimetric observations on Earth have validated this concept. Previous studies have measured circular polarization signals from a variety of living samples – ranging from photosynthetic microorganisms and biofilms to tree leaves and entire vegetation canopies – all of which contain homochiral biopolymers or pigments (Sparks et al.,2009; Patty et al.,2021; Mulder et al.,2022). Notably, airborne and ground-based instruments have successfully detected these signals remotely, distinguishing biotic surfaces from inorganic backgrounds. These observations confirm that circular spectropolarimetry can reliably indicate the presence of life, reinforcing its value as a biosignature detection method.

Biosignatures in Icy Environments:

We extend this biosignature approach to icy worlds. Moons such as Enceladus and Europa eject plume particles from subsurface oceans that could contain microbial life frozen within water-ice grains. However, the presence of water ice (and ice mixed with salts) might modify or obscure polarization signals. Ice and frost are known to strongly influence the linear polarization of reflected light (Poch et al.,2018), which raises the question: will the circular polarization signature of embedded microbes remain discernible in an icy matrix? While no known abiotic process produces a narrow-banded circular polarization signal, multiple scattering in ice could depolarize the light and dampen the signal’s intensity or shift its spectral features, potentially reducing the diagnostic power of the biosignature. To investigate this, we designed experiments to quantify how microbial circular polarization signals behave when microbes are encapsulated in ice particles analogous to those from icy moon plumes.

Experimental Approach:

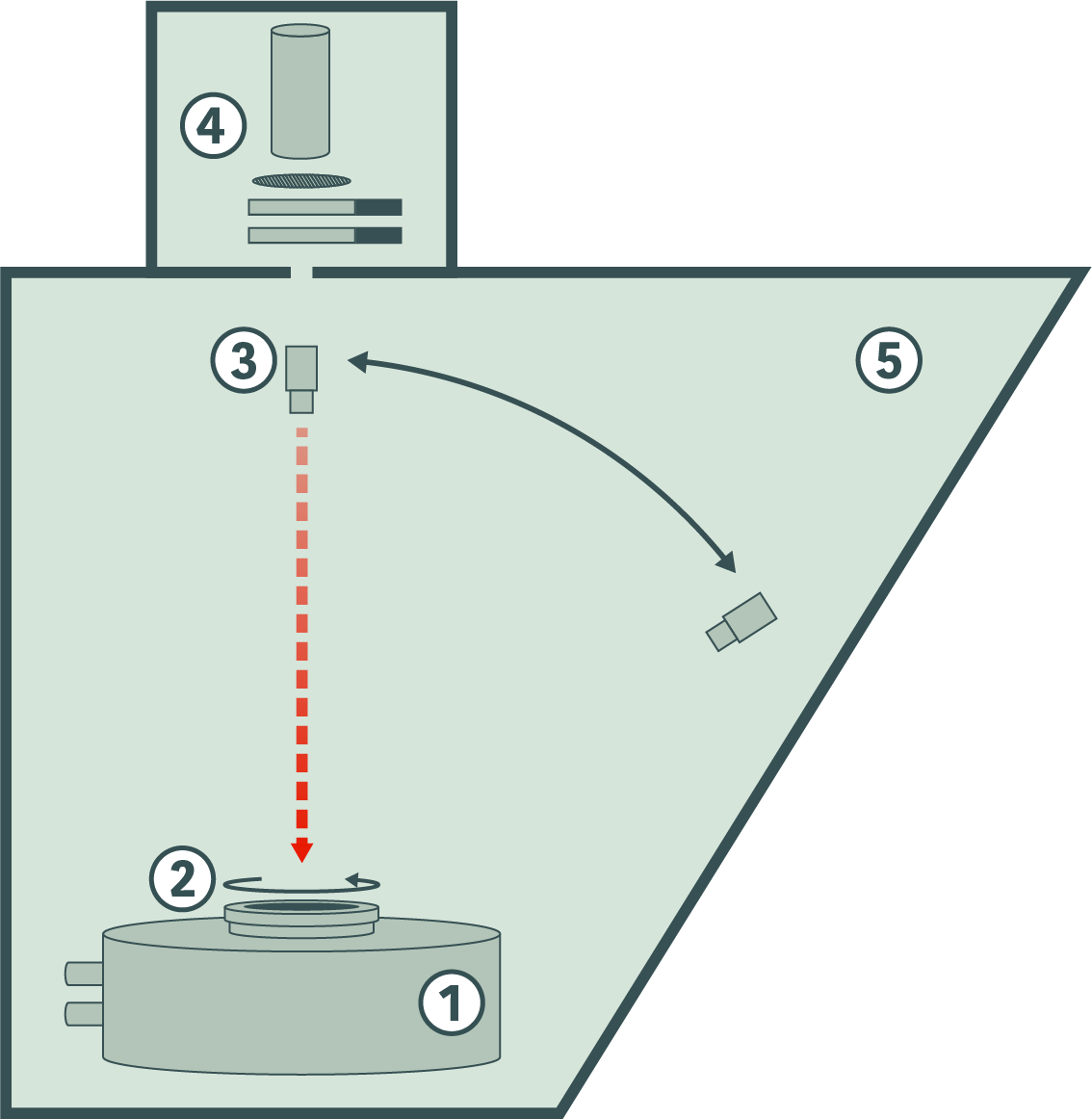

We produced microbe-laden ice analog particles using the Setup for Production of Icy Planetary Analogues B (SPIPA-B) apparatus (Pommerol et al.,2019). SPIPA-B employs an ultrasonic nebulizer to spray droplets of salt brine (with suspended microorganisms) into liquid nitrogen. The rapid flash-freezing in liquid N₂ yields tiny ice spheres with microbes embedded throughout, closely mimicking the formation of plume ice grains under Enceladus-like conditions. The frozen samples were then transferred to the POLarimeter for ICE Samples (POLICES) chamber (Poch et al.,2018; see Fig.2) for analysis. The POLICES facility maintains cryogenic temperatures for the sample and continuously purges the environment with dry nitrogen gas to prevent frost or condensation, creating stable ice conditions for optical measurements.

Using this setup, we measured the light scattered from the icy samples with a highly sensitive, full-Stokes, dual PEM polarimeter by Hinds Instruments with a variable monochromatic light source (see Fig.2). This allowed us to obtain circular polarization spectra of the microbe-bearing ice across visible wavelengths under controlled laboratory conditions. The spectral measurements capture any circular polarizance imparted by the embedded microbes, enabling us to assess how the signal is altered by surrounding ice.

Fig.2: Illustration of the POLICES chamber. 1) Sample holder with liquid nitrogen cooling, 2) sample with variable azimuthal angle, 3) monochromatic light source with a variable phase angle, 4) dual PEM polarimeter, 5) closed chamber purged with dry nitrogen.

Implications:

The results of this experiment (to be presented at EPSC 2025) will elucidate the extent to which ice scattering affects the circular polarization biosignature of microorganisms. This knowledge is crucial for the design of future life-detection missions. If circular polarization signals can penetrate the glare of ice, they could be sought in situ during flybys or plume-sampling missions to astrobiologically relevant sites on icy moons. Conversely, understanding any signal attenuation by ice will help in setting realistic detection limits for those missions. In summary, circular polarization arising from molecular homochirality represents a powerful and uniquely reliable remote-sensing biosignature, and our study advances its applicability to the icy domains that are prime targets in the search for extraterrestrial life.

How to cite: Grone, J., Patty, L., Brandenburg, L., Pommerol, A., Rimle, S., and Demory, B.-O.: Detecting Life in Ice: Circular Polarization as a Remote Biosignature, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1799, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1799, 2025.