- 1Space Research Centre PAS, Warsaw, Poland (dmege@cbk.waw.pl)

- 2Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, GEOPS, 91405 Orsay, France

- 3Institut Universitaire de France (IUF)

Introduction

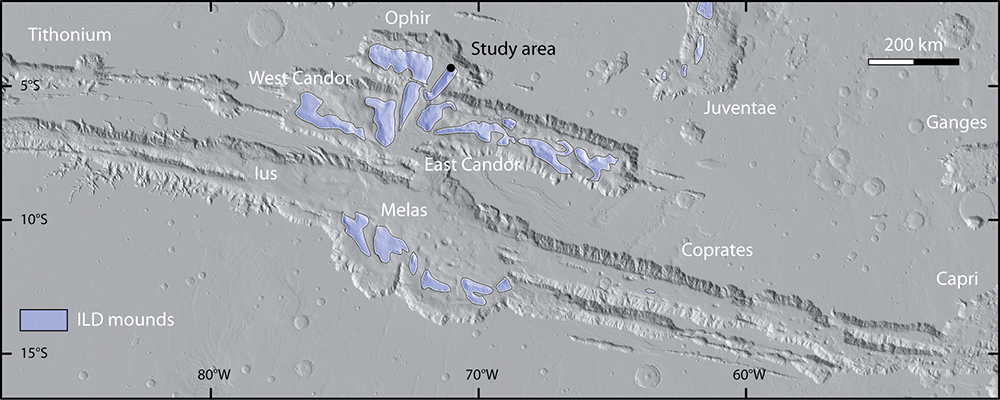

Sulfates are abundant at the Martian surface, incorporating sulfur delivered by volcanic eruptions and degassing [1,2]. The thickest sulfate accumulations are found in the interior layered deposits (ILDs) of Valles Marineris. We have studied them in Ophir Chasma (Figures 1 and 2). They have been interpreted as either purely sedimentary deposits (e.g., [3]) or weathered volcanic products (e.g., [4, 5]).

Spectral analysis

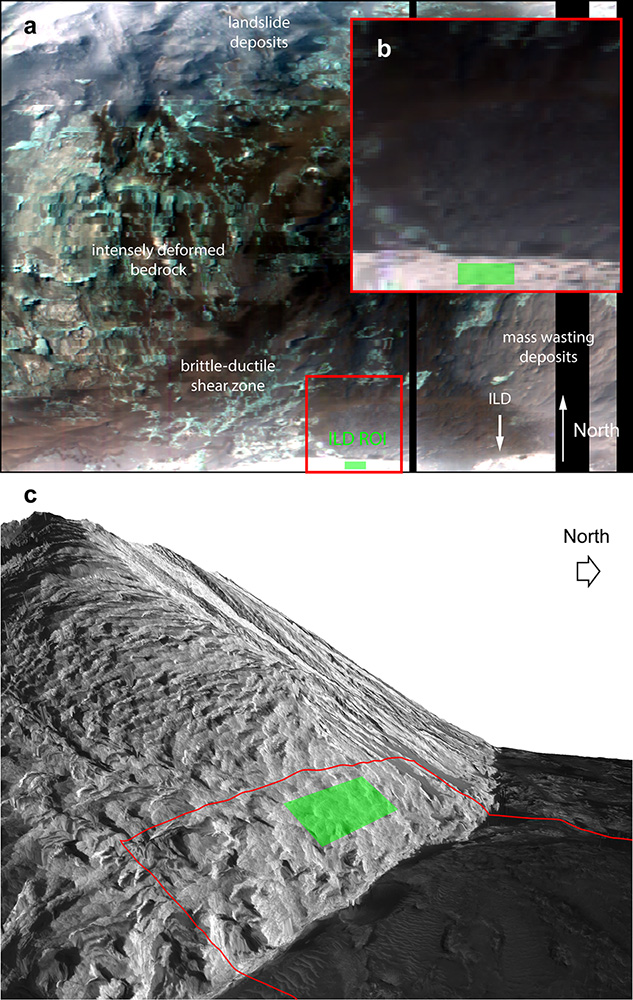

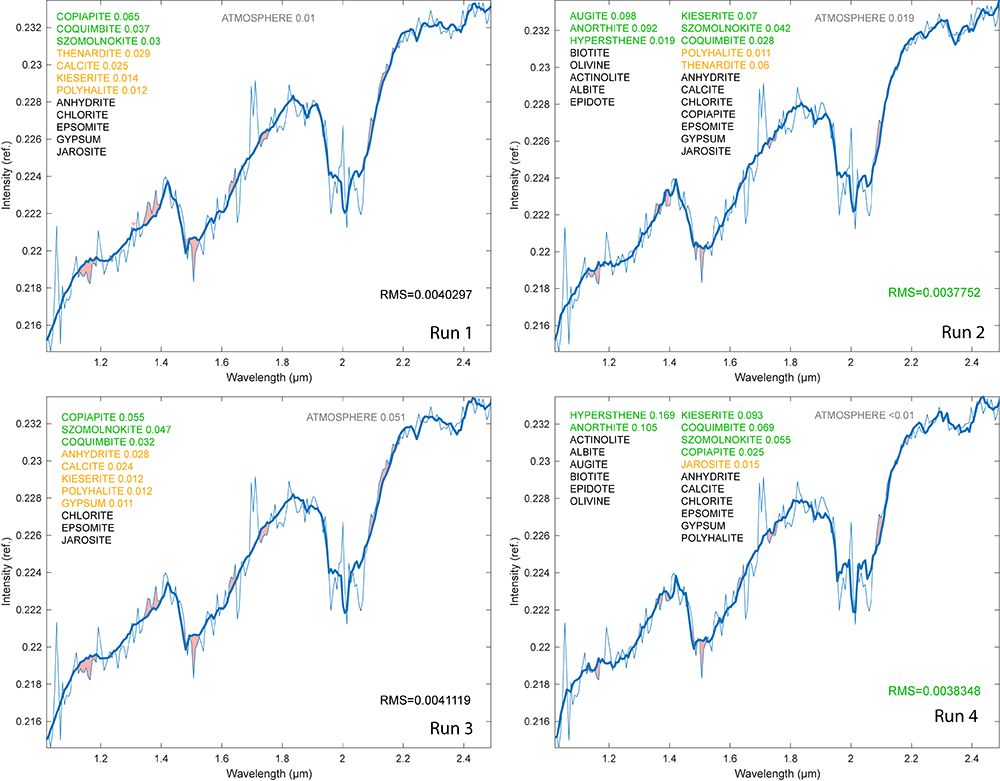

We performed nonlinear spectral unmixing of CRISM data [6] located in the lower, massive member of the ILD pile in Ophir Chasma. The best spectral fit is obtained when primary igneous minerals (orthopyroxene, plagioclase) and coquimbite were present (Figure 3), alongside kieserite and szomolnokite. The latter are thought to be the main mineral constituents of the ILDs [7-11]. Coquimbite is necessary in the spectral mixture to obtain a good spectral fit. Copiapite is possibly present as well.

Analysis of wind patterns and geomorphology

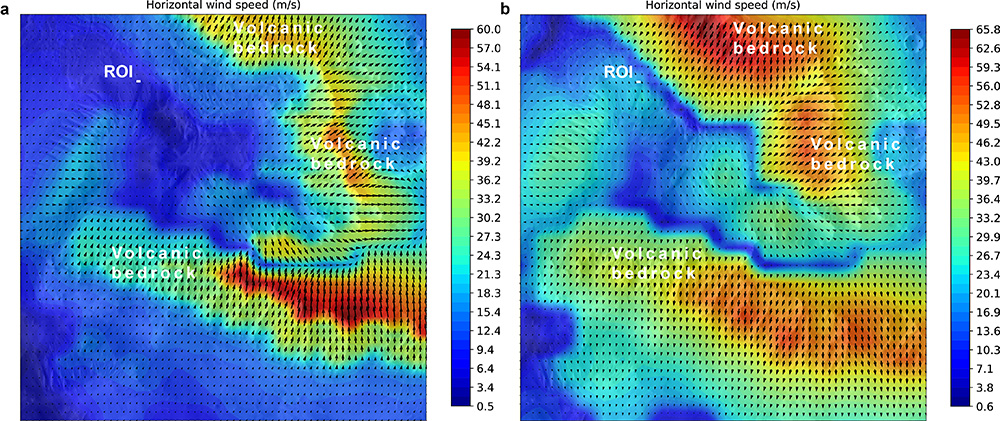

Wind patterns (Figure 4) and geomorphological evidence show that the igneous minerals are from a local source [14, 15] within the ILDs, rather than from wind transportation from neighbouring volcanic plateaus [16].

Results and discussion

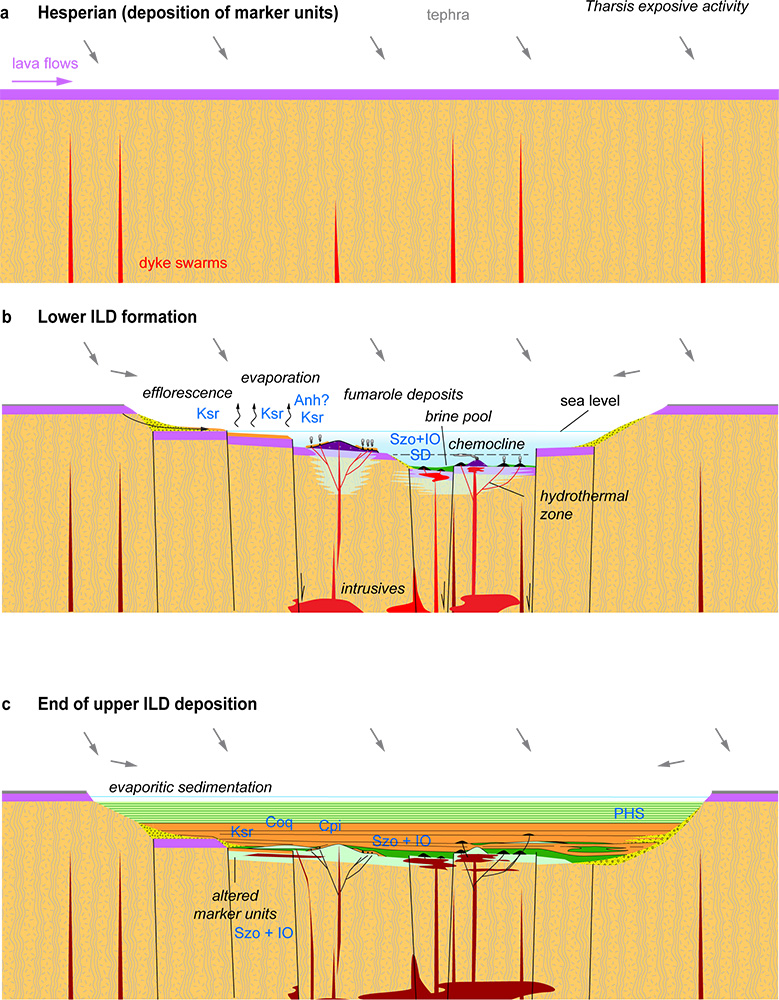

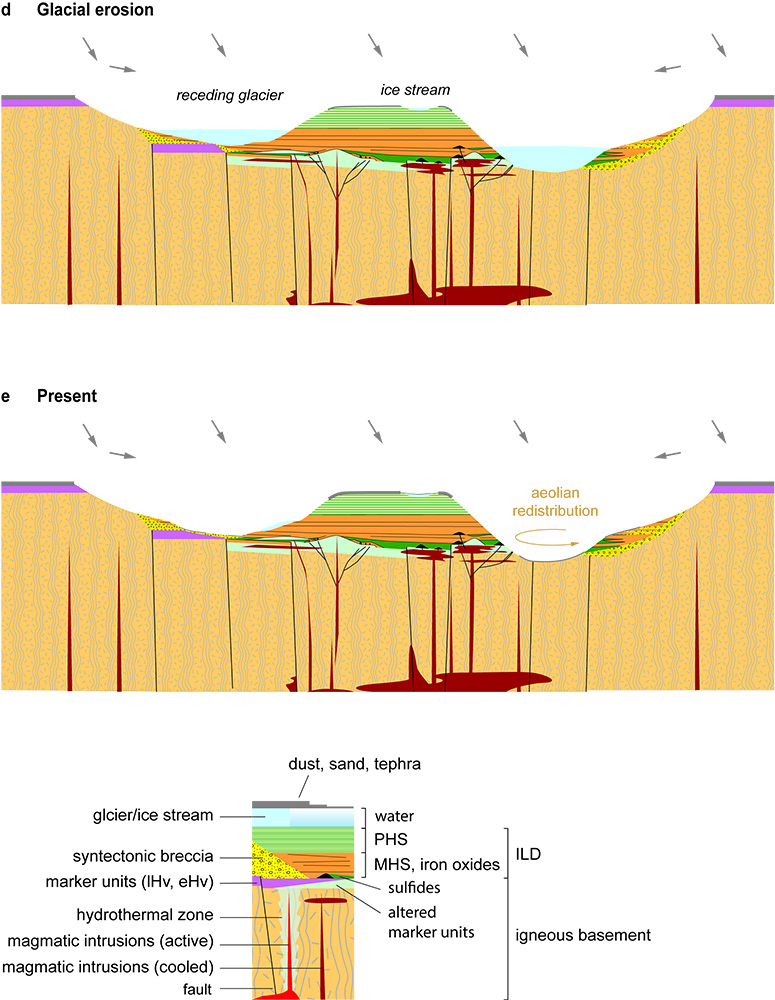

Our findings suggest that the deposition of the lower member of the ILDs was influenced by Tharsis-related syntectonic and synvolcanic activity within the subsided Valles Marineris plateau, and by the redox state of an overlying Valles Marineris sea in a geologic context akin to volcanogenic massive sulfide deposition on Earth. Subsequent climate cooling, potentially related to Tharsis activity waning, would have led to gradual sea freezing, resulting in further alteration in acid-cold environment, and precipitation of the polyhydrated sulfates that compose the upper, layered ILD member. ILD erosion by glacial flows down to the currently exposed chasma floor level and aeolian erosion have shaped the current ILD morphology (Figures 5-6). In summary, the comprehensive ILD pile formed by in-situ weathering of volcanic products, redox state instabilities, and water level fluctuations in a warming and cooling Valles Marineris sea [17].

Figure 1. Main ILD mounds in Valles Marineris.

Figure 2. CRISM and HiRISE views of the ILD region of interest (ROI) studied in this work. (a) Unprojected CRISM cube frt00018b55, also analyzed in another work [6]. The interpretation of geological units is from that work. (b) location of the ILD ROI; (c) Three-dimensional view of part of HiRISE image ESP_017754_1755 (50 cm/pixel), showing ILDs in the South and the approximate location of the ILD ROI. The HiRISE DTM was generated using the HiRISE images ESP_016053_1755 (0.25 m/pixel) and ESP_017754_1755 (0.5 m/pixel).

Figure 3. Outputs of 4 nonlinear spectral unmixing runs. The list of minerals included in the spectral library is given for each run. Runs 2 and 4 share the library used in Runs 1 and 3, respectively, with mafic minerals added. The overall spectral fit is good in all the runs, suggesting that the selected mineral libraries are overall satisfying. The presence of mafic minerals significantly improve the RMS. The red areas illustrate the fit discrepancies in the same representative wavelength ranges for comparison. Minerals in green are considered "detected". In yellow, they are considered "questionable". The value of the mixing coefficients X are given in both cases. The minerals which have a "negligible" or "null" contribution are in black. The value of the mixing coefficient of the atmosphere is indicated in gray.

Figure 4. Speed and direction of horizontal wind at its peak 10 m above the topographic surface. (a) At 20:00 (at longitude 0°), the only fall winds originating from bedrock exposures are located south of the ILD ROI. They do not propagate to the ROI. (b) At 4:00, fall winds originate from the northern chasma slopes. However, fall winds from the ILD slope above the ROI control the wind patterns and the ILDs in the ROI only face fall wind coming from the ILDs upslope. Data are from the Mars Climate Model [12, 13], using the Climatology scenario and solar longitude 180. The latitude and longitude ranges of the covered area are 4°S-5°S and 69.5°W-71.5°W. The width of the displayed area is 175 km.

Figure 5. Mechanisms of ILD deposition and erosion that satisfy the mineralogy interpreted from this and earlier works, stages a-c. Abbreviations: Coq: Coquimbite; Cpi: Copiapite; IO: Iron oxides; Ksr: Kieserite; MHS: Monohydrated sulfates; PHS: Polyhydrated sulfates; Szo: Szomolnokite.

Figure 6. Stages d-e and stratigraphic column.

Cited references

[1] Bibring, J.-P., et al. (2006) Science 312, 400–404. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1122659

[2] King, P. L., & McLennan, S. M. (2010). Elements 6, 107-112. https://doi.org/10.2113/gselements.6.2.107

[3] Grotzinger, J. P., & Milliken, R. E. (2012). In J.P. Grotzinger & R.E. Milliken (Eds.), Sedimentary Geology of Mars, pp. 1–48. https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.12.102.0001

[4] Komatsu, G., et al. (2004) Planetary and Space Science 52, 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2003.08.003

[5] Niles, P. B., & Michalski, J. (2009) Nature Geoscience 2, 215–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/NGEO438

[6] Gurgurewicz, J., et al. (2022) Communications Earth & Environment 3, 282. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00612-5

[7] Noel, A., et al. (2015) Icarus 251, 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2014.09.033

[8] Wendt, L., et al. (2011) Icarus 213, 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2011.02.013

[9] Murchie, S. L., et al. (2009) JGR: Planets 114, E00D05. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JE003343

[9] Roach, L.H., et al. (2010) Icarus 207, 659–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2009.11.029

[10] Weitz, C.M., et al. (2012) JGR: Planets 117, E00J09. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JE004092

[11] Weitz, C.M., et al. (2015) Icarus, 251, 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2014.04.009

[12] Forget, F., et al. (1999) JGR 104, 24155–24175. https://doi.org/10.1029/1999JE001025

[13] Millour, E., et al. (2018) Scientific Workshop From Mars Express to ExoMars, ESA-ESAC and IAA-CSIC, Madrid, Spain.

[14] Chojnacki, M., et al. (2014) Icarus 230, 96–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2013.08.018

[15] Chojnacki, M., et al. (2020) JGR: Planet 125, e2020JE006510. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JE006510

[16] Liu, Y., et al. (2016) JGR: Planets 121, 2004–2036. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JE005028

[17] Mège, D., Gurgurewicz, J., & Schmidt, F., submitted.

How to cite: Mège, D., Gurgurewicz, J., and Schmidt, F.: Altered lava flows and sulfide controls on the formation of layered deposits in Valles Marineris, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-191, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-191, 2025.