- 1Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, United States of America

- 2School of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, Georgia Tech, United States of America

- 3Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Washington University in Saint Louis, United States of America

- 4Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, United States of America

Drone-based ground penetrating radar (DGPR) is a novel tool to retrieve internal properties of debris-covered glaciers, including supraglacial debris thickness, bulk thickness, and detection of englacial debris layers, demonstrating a unique potential of drones to study buried ice reservoirs on Mars [1, 2]. We present the results of surface clutter analysis as part of a project involving a GPR Geodrone 80, centered at 80 MHz, mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 drone.

Since the DGPR platform is above the surface, identification of subsurface interfaces requires the simulation of off-nadir surface reflections (“clutter”) in order to rule out false positive detections from other sources. There is an inherent uncertainty in confirming internal reflectors in our study sites due to sloped surfaces, the presence of boulders, and the proximity to valley walls and trees (Figure 1). Radar surface clutter simulations are employed to model radar returns from off-nadir surface topography and have been successfully used to validate internal reflectors in glaciers in Antarctica [3] using airborne sounding radar, as well as over lobate debris aprons on Mars from orbital sounding radar [4, 5, 6].

Figure 1. Diagram of the DGPR and the detection of subsurface and off-nadir targets. Clutter occurs when the reflection from the off-nadir object returns at a similar travel time to the englacial reflections. (a) A tree A has a return with similar delays to the bottom of the ice B. (b) An off-nadir surface boulder D has a similar return as a buried boulder C. (c) A headwall F has a return with a similar delay as an internal debris layer F.

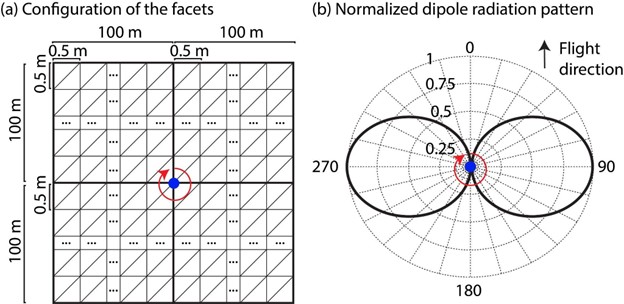

We used digital elevation models (DEMs) derived from drone photogrammetry (~5 cm/px) available for Galena Creek and Sourdough [7] to generate clutter simulations (“cluttergrams”) using state-of-the-art radar surface return simulation software [8. 9]. For each trace in the GPR profile, the clutter simulation software generates a faceted representation of the topography surrounding the drone when the trace was acquired (Figure 2a). Then, the expected reflection power is estimated for each facet using a modified version of the Friis transmission formula (Choudhary et al., 2016) and the two way travel time is calculated from the distance between the drone and the facet center. The reflected power estimates and travel times are assembled into a simulated radar trace for comparison to the GPR data. Given that the antennas of the MALA Geodrone 80 are dipoles (Figure 2b), we use a normalized dipole radiation pattern by multiplying to a factor of the azimuth angle (φ) as shown in equation 1 [10].

Figure 2. (a) Setup of the faceted representation of the topography to generate the clutter simulations. The step size of the facets in both the along and across track is 0.5 m. The total length of the along and across track is based on the time window for each acquisition, in case of a window of 800 ns, the maximum distance to a facet is 100 m. (a) Normalized field patterns of a half-wave dipole antenna. (Visser, H.J., 2012). The red center arrow represents the angle .

We validated three scenarios with the clutter simulator

-

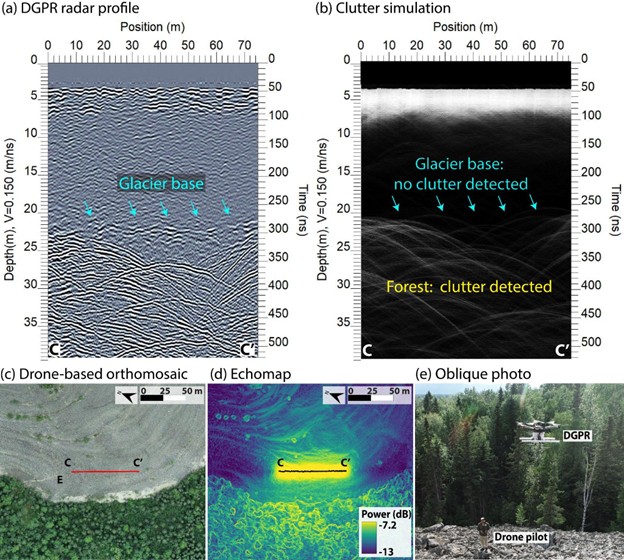

Although there are off-nadir reflectors coming from the forest, the glacier base is still visible in some sections of the profile (Figure 3).

-

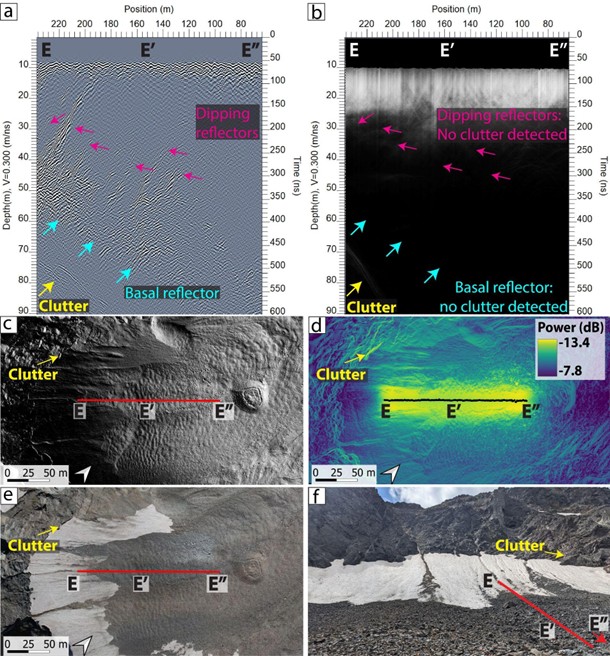

Dipping reflectors interpreted as englacial debris bands are not associated with clutter coming from the headwall (Figure 4).

-

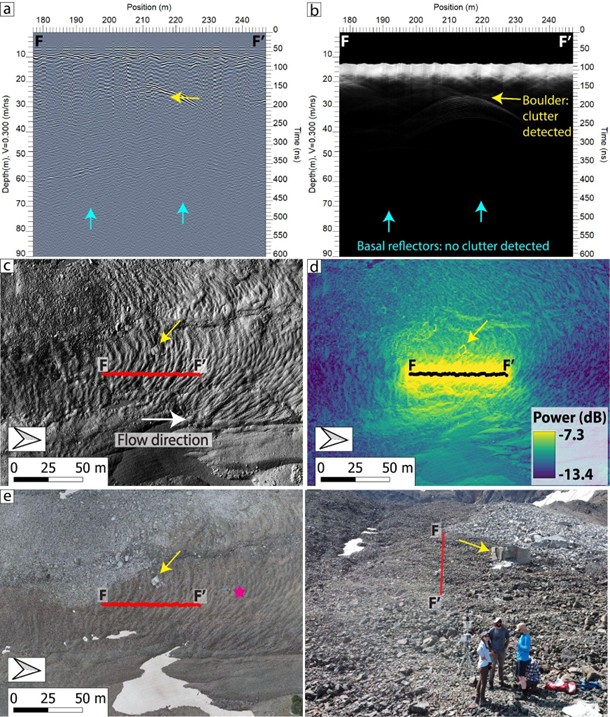

The reflector corresponding to a boulder is not obscuring the englacial reflectors (Figure 5). This reflector could have also been identified as clutter with hyperbola fitting, given that its value is close to the speed of light.

Figure 3. DGPR radar profile (a) and its clutter simulation (b) in the lower section of Sourdough Rock Glacier. The base is a feature observed in the radar profile but not in the clutter simulation. (c) Drone-based orthomosaic with the nadir of the clutter simulation in red (d) Echomap with the first return of the clutter simulation in black. (e) Oblique photo of the DGPR takeoff with the forest in the background, location marked as E in panel c.

Figure 4. Radar profile and clutter simulation at the cirque of Galena Creek. (a) Radar profile with multiple dipping reflectors interpreted as internal debris layers and basal reflectors. (b) Clutter simulation, no clutter was associated with the dipping reflectors or basal reflectors shown in panel a. (c) Hillshade with the nadir return. (d) Power map of the clutter simulation with the first return. (e) Orthomosaic. (f) Ground view with a section of the profile.

Figure 5. Radar profile (a) and clutter simulation (b) of lunch rock in Galena Creek. (c) Hillshade, white arrow indicates the glacier flow direction. (d) Power map of the clutter simulation (e) Orthomosaic indicating the location of the weather station (magenta star) from where the photo in panel f was taken. (f) Ground view. The profile F-F’ in panels c, d, and f shows the first return of the clutter simulation. The yellow arrow indicates the boulder location in all panels.

References

[1] Aguilar et al. (2024) EPSC 2024, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024‐1271. [2] Aguilar et al. (2025) LPSC 2025, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/1693.pdf. [3] Holt et al. (2006) JGR: Planets, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JE002525. [4] Holt et al. (2008) Science, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1164246. [5] Plaut et al. (2009) GRL, Https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL036379. [6] Baker et al. (2019) Icarus, Https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.09.001. [7] Meng et al. (2023b). Journal of Glaciology, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2022.90. [8] Choudhary et al. (2016) IEEE GRSL, https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2016.2581799. [9] Christoffersen et al. (2024) Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10595007. [10] Visser (2012) Antenna Theory and Applications, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119944751.ch5.

How to cite: Aguilar, R., Christoffersen, M., Nerozzi, S., Meng, T., and Holt, J.: Validating internal reflectors from drone-based GPR in debris-covered glaciers with clutter simulations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1936, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1936, 2025.