Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

MITM7

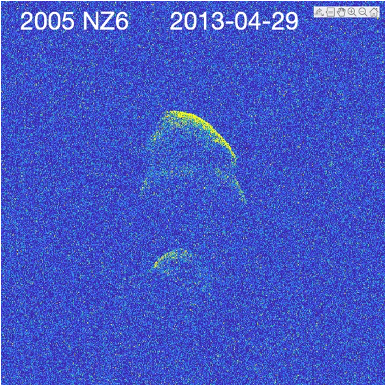

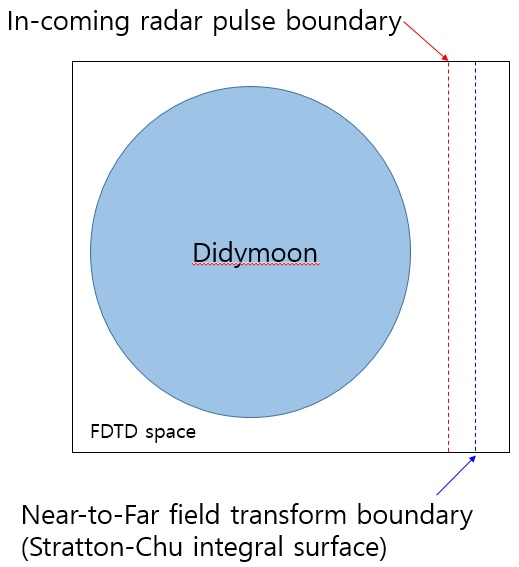

For more than 50 years, the Arecibo Observatory planetary radar explored the Solar System from Earth, including determining the rotation rate of Mercury, detecting liquids on Saturn’s moon Titan, and observing tens to hundreds of NEOs yearly, many with sufficient data for detailed analysis of surface morphology and 3-D shape reconstruction. Current radar facilities continue monitoring near-Earth space (e.g., Goldstone), as well as emerging capabilities at Green Bank Observatory and southern hemisphere observing capabilities in Australia. Various radar observing methods have also been used to study Solar System bodies in orbit, including synthetic aperture radar imagers (e.g., the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s Mini-RF), and sounders (e.g., Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s SHARAD). Many more such instruments are en route (e.g., RIME on JUICE and REASON on Clipper for Ganymede and Europa, as well as JuRa for 65803 Didymos) and others are in development (e.g., SRS on EnVision, and VISAR on VERITAS for Venus), as well as planned instruments for small body exploration, including the upcoming close-approach of 99942 Apophis (e.g., RAMSES).

In this session, we invite contributions relating to ground- and space-based planetary radars, from the analysis of existing missions and facilities, laboratory and field-analog studies, to instrument development, and new techniques to conduct radar studies.

Session assets

Introduction

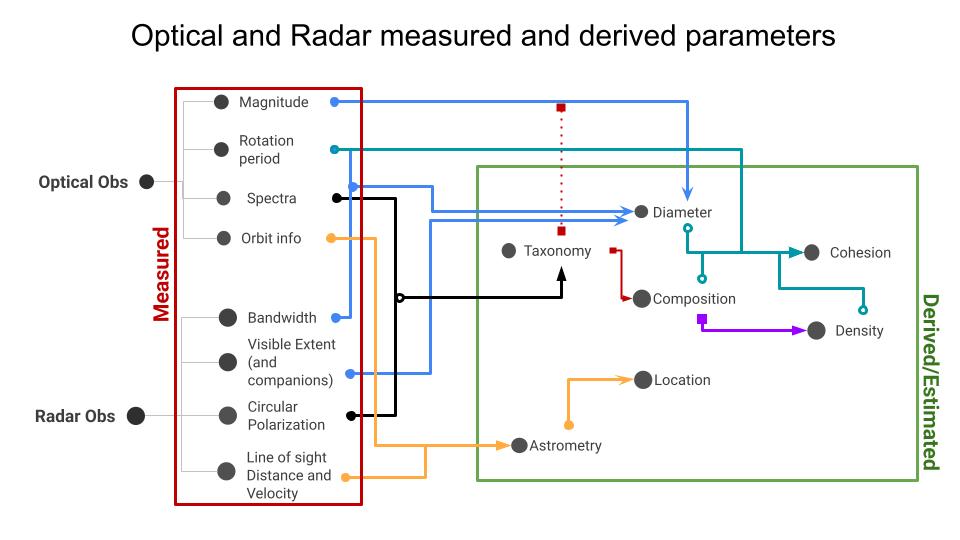

Planetary radar observations provide a powerful tool for the post-discovery characterization of the physical and dynamical properties of asteroids, comets, the Moon, and terrestrial planets. Radar observations of near-Earth objects (NEOs) [e.g., 1] have increased our understanding of the diversity of NEO sizes, shapes, binarity, and composition. These characteristics are crucial also to planetary defense as they play a role in the selection of the optimal mitigation technique. Planetary radar systems can be used for range-Doppler imaging by mapping the reflected power as a function of the Doppler frequency and the range (based on the signal’s round-trip time), which allows imaging resolutions finer than 10 meters at best, and thus direct observations of morphologic features and possible moons. The data can be obtained at two orthogonal polarization states.

Due to the penetration depth of several wavelengths and the wide parameter space in scattering inversion problems, understanding the physical characteristics of NEOs based on their radar scattering profiles requires extensive numerical modeling. Traditionally, circular polarization ratio has been used as a first-order gauge to the surface roughness, but more recent advances in numerical modeling demonstrate that analyzing the reflectivity information in parallel with the polarization information is crucial (e.g., [2-3]). This allows distinguishing different scattering processes. For example, the disk function of (101955) Bennu shows little to no specular component, which indicates that wavelength-scale particles dominate the surface; a fact not available from the polarization ratio information alone. For contrast, the Moon has a strong quasi-specular spike, which is consistent with the fact that fine-grained regolith dominates the lunar surface.

Analytically derived scattering models typically assume that the surface is composed primarily of fine-grained regolith or a solid surface that forms a gently undulating interface with few or no wavelength-scale scatterers. This assumption has been reasonable for the surfaces of the terrestrial planets and moons but is not sufficient for asteroids that have often a “rubble-pile structure” and, as such, the asteroid surfaces have often a significantly greater coverage of centimeter-to-decimeter scale regolith than planets or moons. Empirical laws lack understanding of the meaning of the empirical fit parameters. In this presentation, I discuss the recent advances in scattering modeling methods and future requirements for improved interpretation of radar observations.

Aims

Here, we present recent advances in the modeling efforts of radar scattering for the characterization of planetary bodies. The goal is to improve planetary surface characterization by better interpretation of radar observations. As research has shown, examples of physical properties that can be derived include the near-surface density, regolith size-frequency distributions of centimeter-to-decimeter scale particles, and subsurface permittivity contrast that provides clues to the internal structure and composition.

Methods

The radar scattering processes in planetary bodies includes two components: Scattering by the undulating surface and scattering by the wavelength-scale particles. As the main part of this work, we conducted numerical computations of scattering properties of rough polyhedral particles 1) in touch with a surface to simulate surface particles [6], and 2) embedded in a host medium. In the first case, we investigate the roles of size parameter (x=2πr/λ, where r is the effective particle radius and λ is the wavelength) and the refractive properties. We selected two different refractive indices for comparative analysis: 2.17 + 0.004i and 2.79 + 0.0155i (particles) on a substrate with 1.55 + 0.004i, and two polyhedral morphologies with statistically distinct levels of roundness. In the second case, the refractive contrast relative to the host medium is compared for 1.4 and 1.8. Also, the effect of the particle packing density is investigated for the radiative transfer approximation with and without coherent backscattering included. The size-frequency distribution of regolith typically follows a power-law distribution with a power index of 2.5–3.5; a comparable size distribution range is used also in our numerical simulations. The range of sizes extends from sub-wavelength scale to several wavelengths.

For scattering by a fine-grained regolith substrate, we built synthetic rough surfaces and simulated radar scattering as a function of incidence angle using a geometric-optics approximation [4]. We used self-affine fractal surfaces, which are described using a horizontal-scale-dependent height standard deviation and Hurst exponent, because they have been shown to be more realistic for rocky surfaces than stationary surfaces. Research has shown that the Gaussian scattering law provides a good approximation for scattering by self-affine fractal surfaces [4,5].

Summary of the results

This work discusses and illustrates the different scattering processes taking place in planetary surfaces and what role they play in the observable parameters. The main part of the work discusses the role of particles on surfaces and below the surface. We find that for surface particles with a refractive index above 2.17, the refractive index plays an insignificant role in comparison to the particle abundance and shape, and that the surface-particle interaction is weak [6]. For particles embedded in the substrate, the contrast between the particles and host medium plays a noticeable role in the observed polarization and reflectivity. Coherent backscattering produces a significant enhancement, as expected. We discuss how to identify coherent backscattering – a signature of low-absorption substances such as water ice – when observations at a range of phase angles are not available.

References

[1] Virkki, A. K. et al. (2022), Planetary Science Journal, 3, 222.

[2] Virkki, A. K. & Bhiravarasu, S. S. (2019), Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 124, 11.

[3] Hickson, D. C., et al. (2021), Planetary Science Journal 2, 30.

[4] Virkki, A. K. (2024), Remote Sensing 16, 890.

[5] Shepard M. K. et al. (1995), Journal of Geophysical Research 100, E6, 709.

[6] Virkki, A. K. & Yurkin, M. A. (2025), In revision. Pre-print available at https://arxiv.org/abs/arXiv:2501.10019.

How to cite: Virkki, A. and Leppälä, A.: Recent advances in planetary surface characterization using modeling of radar scattering, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-52, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-52, 2025.

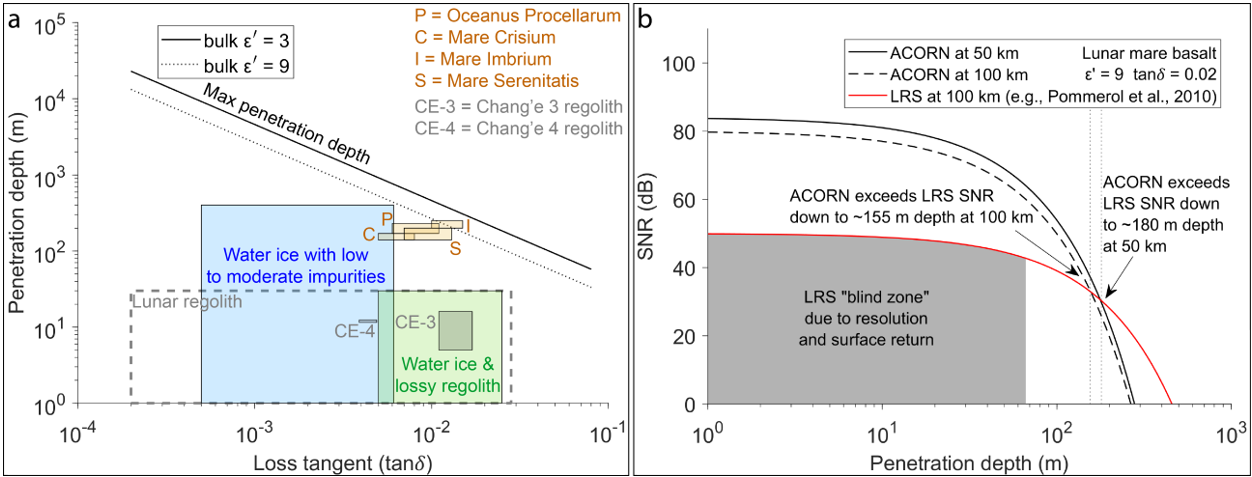

Planetary bodies can be affected by a number of geologic processes, including impacts, volcanism, volatile deposition, mass wasting, and weathering. Local stratigraphic sequences record the effects of these processes like a time capsule, revealing how geologic processes have shaped the site through time. Many geologic processes leave their fingerprints within the stratigraphy on many meters to decameters scales. While most remote sensing techniques are sensitive only to surface materials at the shallowest (µm to m) depth scales, radio frequencies (RF) are well poised for geologic characterization of planetary bodies at these deeper scales, providing insight on regolith thickness, subsurface deposits, and geologic chronology.

Ground penetrating radar (GPR) sounding is a non-invasive geophysical technique often employed to sense the subsurface that has been used on Earth, the Moon (the Chang’E 3 and 4 Yutu rovers’ Lunar Penetrating Radars, and the orbital Kaguya Lunar Radar Sounder), and Mars (the Mars Perseverance Rover’s RIMFAX, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s SHARAD, and Mars Express’ MARSIS instruments), with Europa Clipper’s REASON instrument currently en route to Europa. Collecting GPR data, however, requires lateral translation of the antenna(s) to build up a 2D profile of the subsurface, adding risk and operational complexity. Additionally, a major challenge in interpreting traditional 2D GPR data is subsurface “clutter,” signals returned at the same time as subsurface targets of interest which disguise signals from the target.

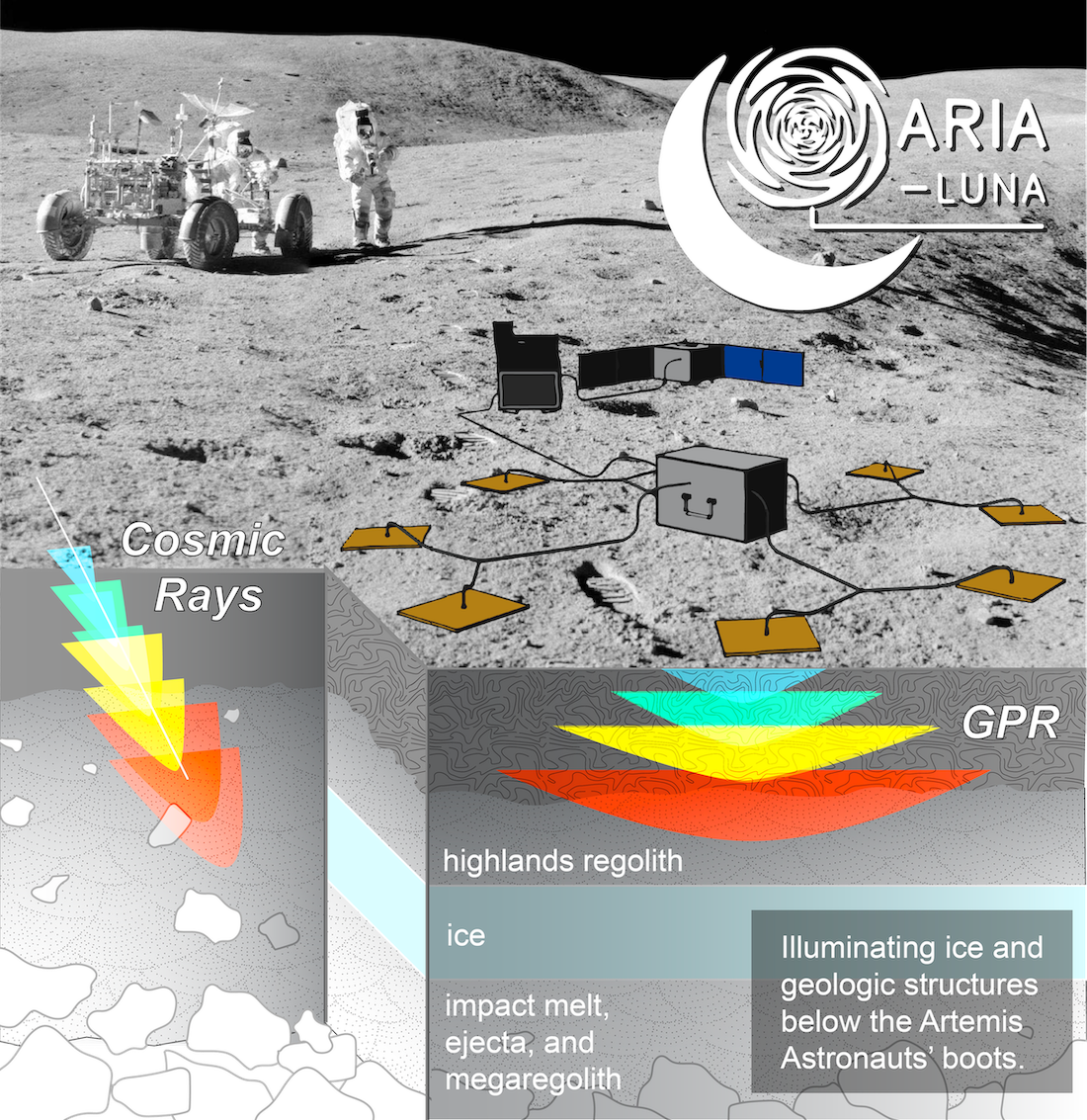

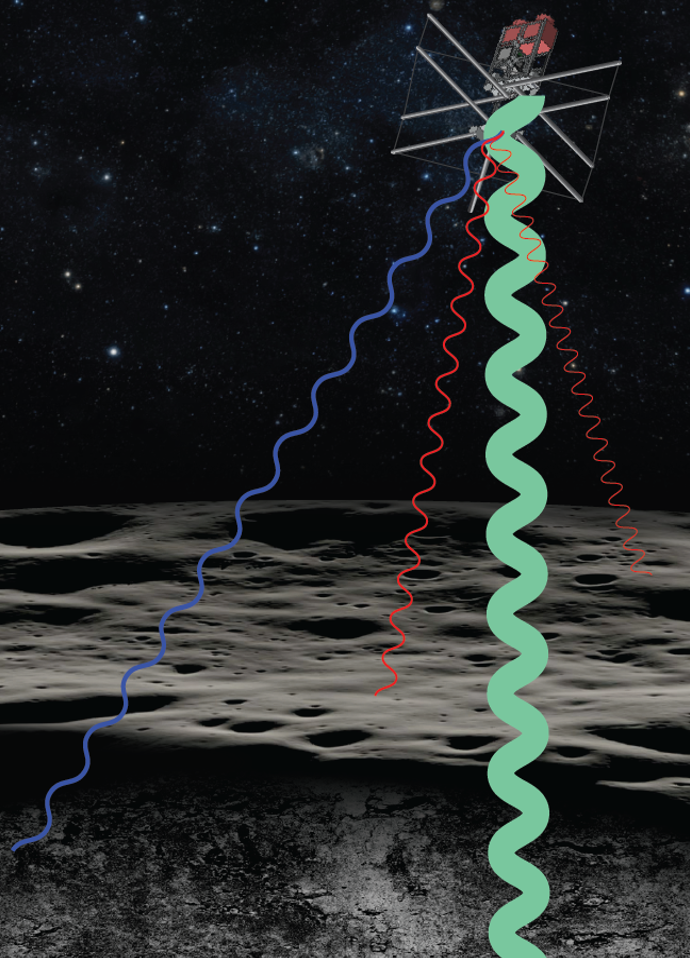

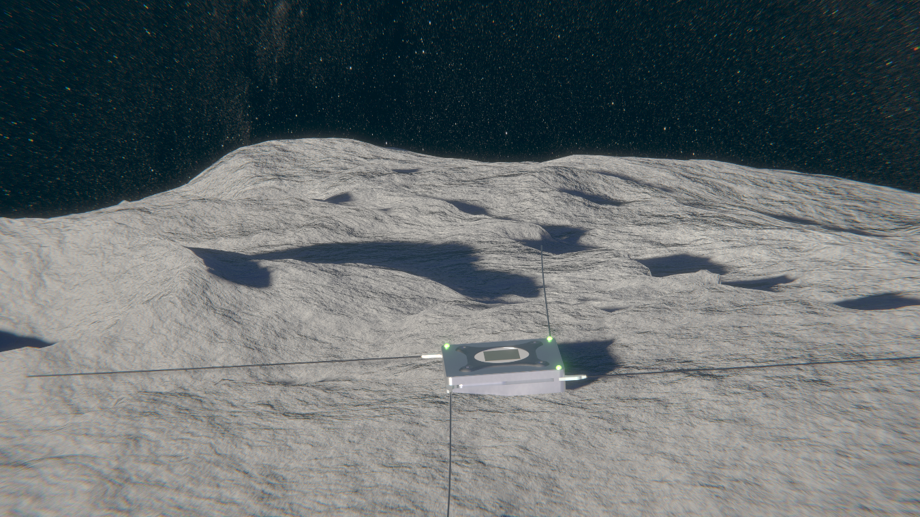

Here, we present a surface-deployed RF instrument concept under development, which we call ARIA (the Askaryan Regolith Imaging Array) (Fig.1). ARIA features a dual-polarization, bistatic antenna array that measures full Stokes parameters and applies interferometric techniques that have never before been used for planetary radar, providing an unprecedented opportunity for 3D subsurface imaging at a landing site — all while stationary. ARIA utilizes a unique combination of traditional and cutting-edge RF techniques, including: active GPR, bistatic radar methods that capitalize on cosmic rays as a natural RF source, and passive radiometry for temperature profiling.

ARIA’s active radar system features a circularly-polarized transmit antenna that measures regolith properties, buried geologic units, and rocks embedded in the subsurface through the spectral, temporal, and polarimetric characteristics of radio signals received at 250–750 MHz using dual-polarized sinuous antennas, employed as a beamforming array to provide both lateral and depth resolution.

ARIA’s passive bistatic radar observes radio emission from cosmic ray cascades within the regolith, which illuminate an extended radius surrounding the antenna array. These relativistic particle cascades create highly impulsive, 100% linearly-polarized radio emission via the Askaryan effect (Saltzberg et al. 2001), a well-known and studied electrodynamic process in high energy physics, which has not previously been exploited for planetary science.

ARIA can also operate as a passive radiometer, measuring the RF spectra from 250 MHz out to 1500 MHz. Different frequencies are sensitive to temperatures at different depths, which can be exploited to constrain geothermal gradient (Siegler et al. 2023; Brown et al. 2023). ARIA would use its radiometric measurements in concert with independent constraints on dielectric properties from its other RF techniques to help pioneer a technique for measuring geothermal heat flux without the need to drill.

With ARIA, we can address many outstanding questions in lunar and planetary science, such as:

- Are there subsurface deposits of ice in the cold polar regions of the Moon?

- What is the thickness of the regolith at a given landing site, and what is the nature of the regolith-megaregolith contact?

- Are there buried impact ejecta or melt deposits present in the subsurface, illuminating the chronology of impact processes that have occurred in that region?

- How thick are individual volcanic units, what are the stratigraphic relationships between them, and how do these units vary laterally?

- What is the geothermal heat flux at a given landing site?

Figure 1: An implementation of ARIA depicted on the lunar surface.

Cosmic ray RF sounding was recently recognized in a report (CLOC-SAT, 2022) commissioned by the Lunar Exploration and Analysis Group. We can use the cosmic ray spectrum and radio emission properties to cross-calibrate the active GPR results. Using ARIA’s beamforming methods, we are able to map cosmic ray events to their reflection points, and ultimately back to the shower vertex. From the cosmic ray methodology, we can directly measure dielectric parameters of the regolith and subsurface interfaces, a capability not possible with traditional GPR, which must assume a dielectric constant to infer a given target’s depth. This methodology has been demonstrated by the NASA-funded Antarctic Impulsive Transient Antenna (ANITA) stratospheric balloon payloads (Gorham et al. 2009), and was used to measure Antarctic ice properties (e.g., Prohira et al. 2018). ARIA would be the first extension of this cosmic ray methodology beyond Earth.

While here we focus on deployment of the ARIA instrument on the lunar surface, simulations by Costello et al. (2025) show that cosmic ray-induced RF showers could be detectable from a sensor deployed in orbit. Tai Udovicic et al. (2025) suggest hundreds of events should be observable from the Moon’s permanently shadowed regions during a 2-year mission with the Cosmic Ray Lunar Sounder (CoRaLS) detector in an LRO-like orbit. Simulations also show that utilizing RF pulses generated by the Askaryan Effect yield capabilities for sensing subsurface layers thinner than that detectable by more traditional radar sounding or synthetic aperture radar methods. Additionally, ARIA can be integrated with other instrumentation (e.g., a seismometer suite) for comprehensive and complementary investigations (Bramson et al. 2023). Lastly, while the Moon is a logical location to employ an instrument like ARIA, the utility of this RF instrumentation could be realized for many applications across the Solar System (Prechelt et al. 2022).

References:

Bramson et al. (2023) 54th LPSC, Abstract #1797,

https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2023/pdf/1797.pdf.

Brown et al. (2023) JGR-Planets, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007609.

Costello et al. (2025) GRL, https://doi.org/10.1029/2024GL113304.

Gorham et al. (2009) Astroparticle Physics, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.astropartphys.2009.05.003.

Greenhagen, Pieters, Glotch, and the CLOC-SAT Specific Action Team (2022). Continuous Lunar Orbital Capabilities Specific Action Team Report. Lunar Exploration Analysis Group.

Prechelt et al. (2022) arXiv:astro-ph.EP, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2212.07689.

Prohira et al. (2018) Phys. Rev. D, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.98.042004.

Saltzberg et al. (2001) Phys. Rev. Lett., https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.2802.

Siegler et al. (2023) Nature, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06183-5.

Tai Udovicic et al. (2025) 56th LPSC, Abstract #2860,

https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/2860.pdf.

How to cite: Bramson, A., Gorham, P., and Costello, E. and the ARIA Proposal Teams: ARIA (Askaryan Regolith Imaging Array): An Instrument Concept for Novel Radio Frequency Characterization of Planetary Subsurfaces, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1208, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1208, 2025.

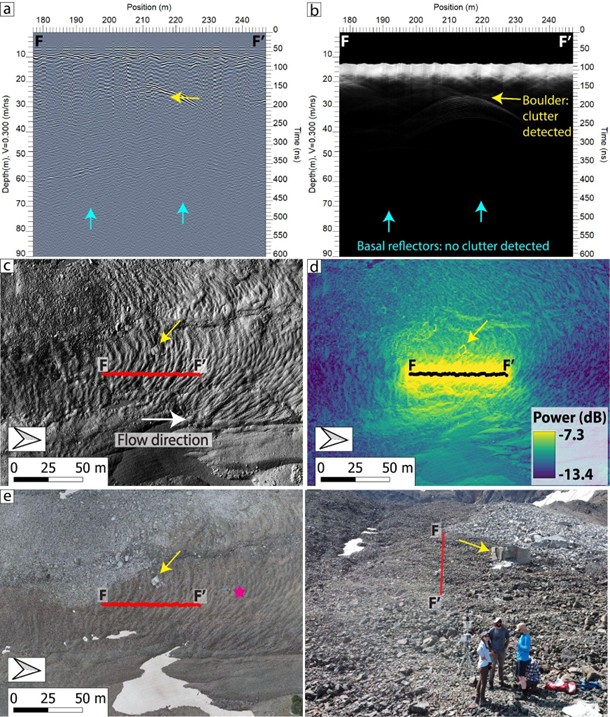

Drone-based ground penetrating radar (DGPR) is a novel tool to retrieve internal properties of debris-covered glaciers, including supraglacial debris thickness, bulk thickness, and detection of englacial debris layers, demonstrating a unique potential of drones to study buried ice reservoirs on Mars [1, 2]. We present the results of surface clutter analysis as part of a project involving a GPR Geodrone 80, centered at 80 MHz, mounted on a DJI Matrice 600 drone.

Since the DGPR platform is above the surface, identification of subsurface interfaces requires the simulation of off-nadir surface reflections (“clutter”) in order to rule out false positive detections from other sources. There is an inherent uncertainty in confirming internal reflectors in our study sites due to sloped surfaces, the presence of boulders, and the proximity to valley walls and trees (Figure 1). Radar surface clutter simulations are employed to model radar returns from off-nadir surface topography and have been successfully used to validate internal reflectors in glaciers in Antarctica [3] using airborne sounding radar, as well as over lobate debris aprons on Mars from orbital sounding radar [4, 5, 6].

Figure 1. Diagram of the DGPR and the detection of subsurface and off-nadir targets. Clutter occurs when the reflection from the off-nadir object returns at a similar travel time to the englacial reflections. (a) A tree A has a return with similar delays to the bottom of the ice B. (b) An off-nadir surface boulder D has a similar return as a buried boulder C. (c) A headwall F has a return with a similar delay as an internal debris layer F.

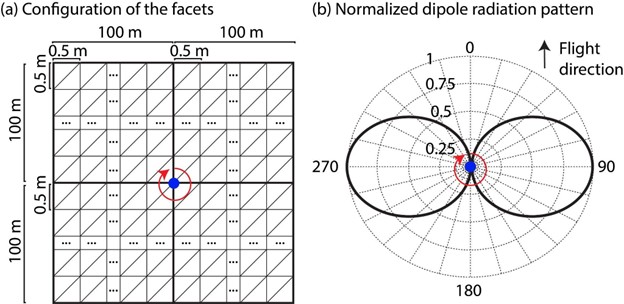

We used digital elevation models (DEMs) derived from drone photogrammetry (~5 cm/px) available for Galena Creek and Sourdough [7] to generate clutter simulations (“cluttergrams”) using state-of-the-art radar surface return simulation software [8. 9]. For each trace in the GPR profile, the clutter simulation software generates a faceted representation of the topography surrounding the drone when the trace was acquired (Figure 2a). Then, the expected reflection power is estimated for each facet using a modified version of the Friis transmission formula (Choudhary et al., 2016) and the two way travel time is calculated from the distance between the drone and the facet center. The reflected power estimates and travel times are assembled into a simulated radar trace for comparison to the GPR data. Given that the antennas of the MALA Geodrone 80 are dipoles (Figure 2b), we use a normalized dipole radiation pattern by multiplying to a factor of the azimuth angle (φ) as shown in equation 1 [10].

Figure 2. (a) Setup of the faceted representation of the topography to generate the clutter simulations. The step size of the facets in both the along and across track is 0.5 m. The total length of the along and across track is based on the time window for each acquisition, in case of a window of 800 ns, the maximum distance to a facet is 100 m. (a) Normalized field patterns of a half-wave dipole antenna. (Visser, H.J., 2012). The red center arrow represents the angle .

We validated three scenarios with the clutter simulator

-

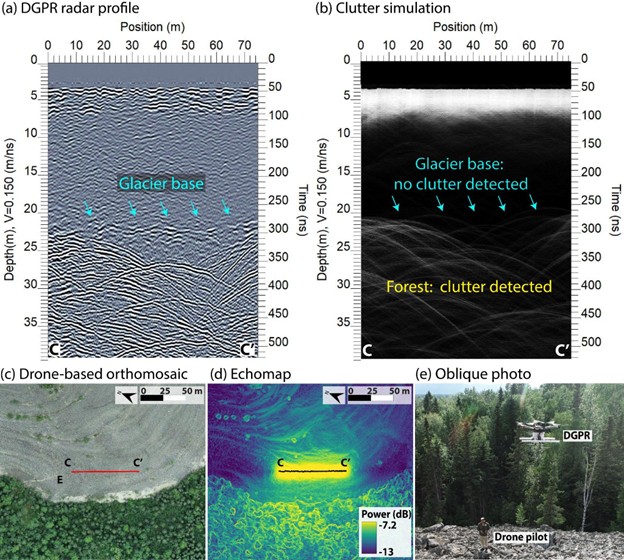

Although there are off-nadir reflectors coming from the forest, the glacier base is still visible in some sections of the profile (Figure 3).

-

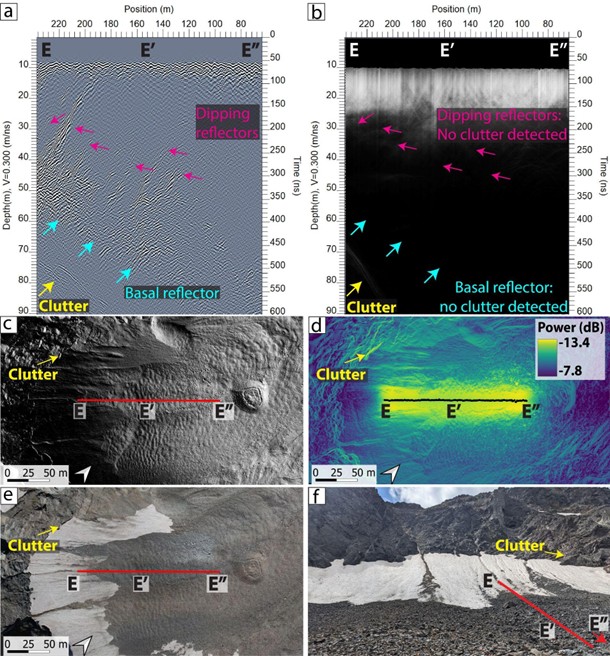

Dipping reflectors interpreted as englacial debris bands are not associated with clutter coming from the headwall (Figure 4).

-

The reflector corresponding to a boulder is not obscuring the englacial reflectors (Figure 5). This reflector could have also been identified as clutter with hyperbola fitting, given that its value is close to the speed of light.

Figure 3. DGPR radar profile (a) and its clutter simulation (b) in the lower section of Sourdough Rock Glacier. The base is a feature observed in the radar profile but not in the clutter simulation. (c) Drone-based orthomosaic with the nadir of the clutter simulation in red (d) Echomap with the first return of the clutter simulation in black. (e) Oblique photo of the DGPR takeoff with the forest in the background, location marked as E in panel c.

Figure 4. Radar profile and clutter simulation at the cirque of Galena Creek. (a) Radar profile with multiple dipping reflectors interpreted as internal debris layers and basal reflectors. (b) Clutter simulation, no clutter was associated with the dipping reflectors or basal reflectors shown in panel a. (c) Hillshade with the nadir return. (d) Power map of the clutter simulation with the first return. (e) Orthomosaic. (f) Ground view with a section of the profile.

Figure 5. Radar profile (a) and clutter simulation (b) of lunch rock in Galena Creek. (c) Hillshade, white arrow indicates the glacier flow direction. (d) Power map of the clutter simulation (e) Orthomosaic indicating the location of the weather station (magenta star) from where the photo in panel f was taken. (f) Ground view. The profile F-F’ in panels c, d, and f shows the first return of the clutter simulation. The yellow arrow indicates the boulder location in all panels.

References

[1] Aguilar et al. (2024) EPSC 2024, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024‐1271. [2] Aguilar et al. (2025) LPSC 2025, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2025/pdf/1693.pdf. [3] Holt et al. (2006) JGR: Planets, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005JE002525. [4] Holt et al. (2008) Science, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1164246. [5] Plaut et al. (2009) GRL, Https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL036379. [6] Baker et al. (2019) Icarus, Https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.09.001. [7] Meng et al. (2023b). Journal of Glaciology, https://doi.org/10.1017/jog.2022.90. [8] Choudhary et al. (2016) IEEE GRSL, https://doi.org/10.1109/LGRS.2016.2581799. [9] Christoffersen et al. (2024) Zenodo, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10595007. [10] Visser (2012) Antenna Theory and Applications, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119944751.ch5.

How to cite: Aguilar, R., Christoffersen, M., Nerozzi, S., Meng, T., and Holt, J.: Validating internal reflectors from drone-based GPR in debris-covered glaciers with clutter simulations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1936, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1936, 2025.

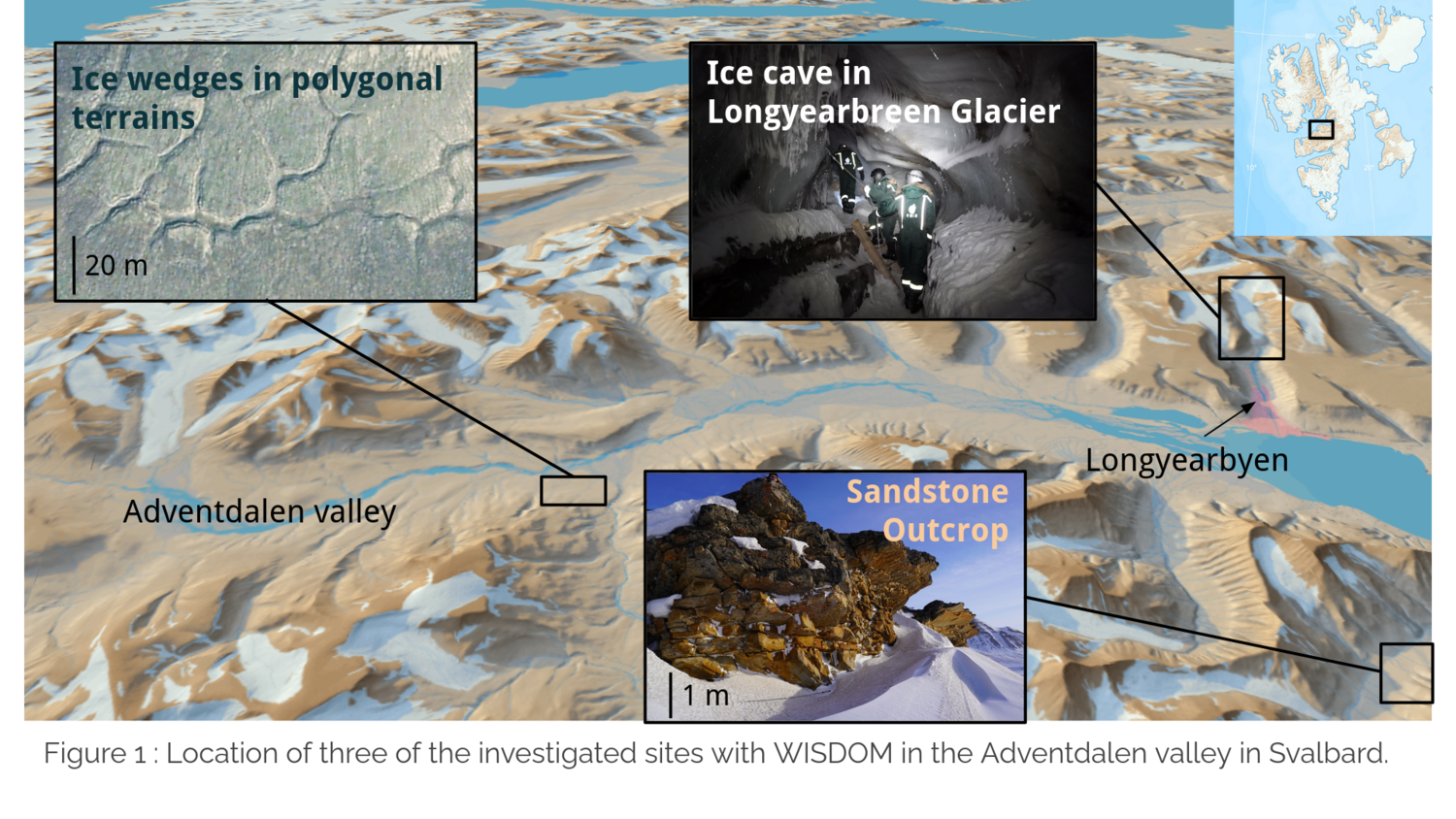

Introduction

The investigation of the subsurface of Mars provides key insights into its geological history and reveal signs of extinct life. This is why the ExoMars/Rosalind Franklin rover mission has been designed to search for biosignature in the subsurface of Oxia Planum [1], especially thanks to a drill [2] able to collect samples down to 2 m below the surface. The WISDOM GPR [3] aboard the rover will guide the the selection of suitable and safe underground targets. For this purpose, WISDOM will probe the Martian subsurface at frequencies in the 0.5-3 GHz range, guaranteeing a centimetric resolution and a penetration depth of a few meters.

Field test campaigns in partially controlled or natural environments are of the outmost importance to assess WISDOM performance and validate the data processing chain. This paper presents interpretation tools developed and applied to experimental data acquired with the flight spare model of WISDOM during a field test campaign in Svalbard in March 2022. Svalbard already hosted the AMASE campaigns [4] between 2007 and 2011 to prepare the ExoMars mission. Svalbard’s permafrost is very favourable to the penetration of waves and the main goal of this campaign was to collect data in a well-documented geological and glaciological environment [5;6]. Besides, the regions includes polygonal terrains, caves and outcrops that can be regarded as relevant Martian analogues.

Svalbard field test location

The WISDOM data presented in this paper have been acquired in March 2022 in the Adventdalen Valley, near Longyearbyen. The map Fig. 1 shows 3 investigated terrains namely

(i) Ice cave meanders 6 to 10 m deep inside the glacier.

(ii) A heavily fractured sandstone outcrop (25-m long profile). Outcrops will be amongst the ExoMars rover's priority targets to drill and seek for biosignature.

(iii) A polygonal terrain (four parallel lines crossing two polygon troughs).

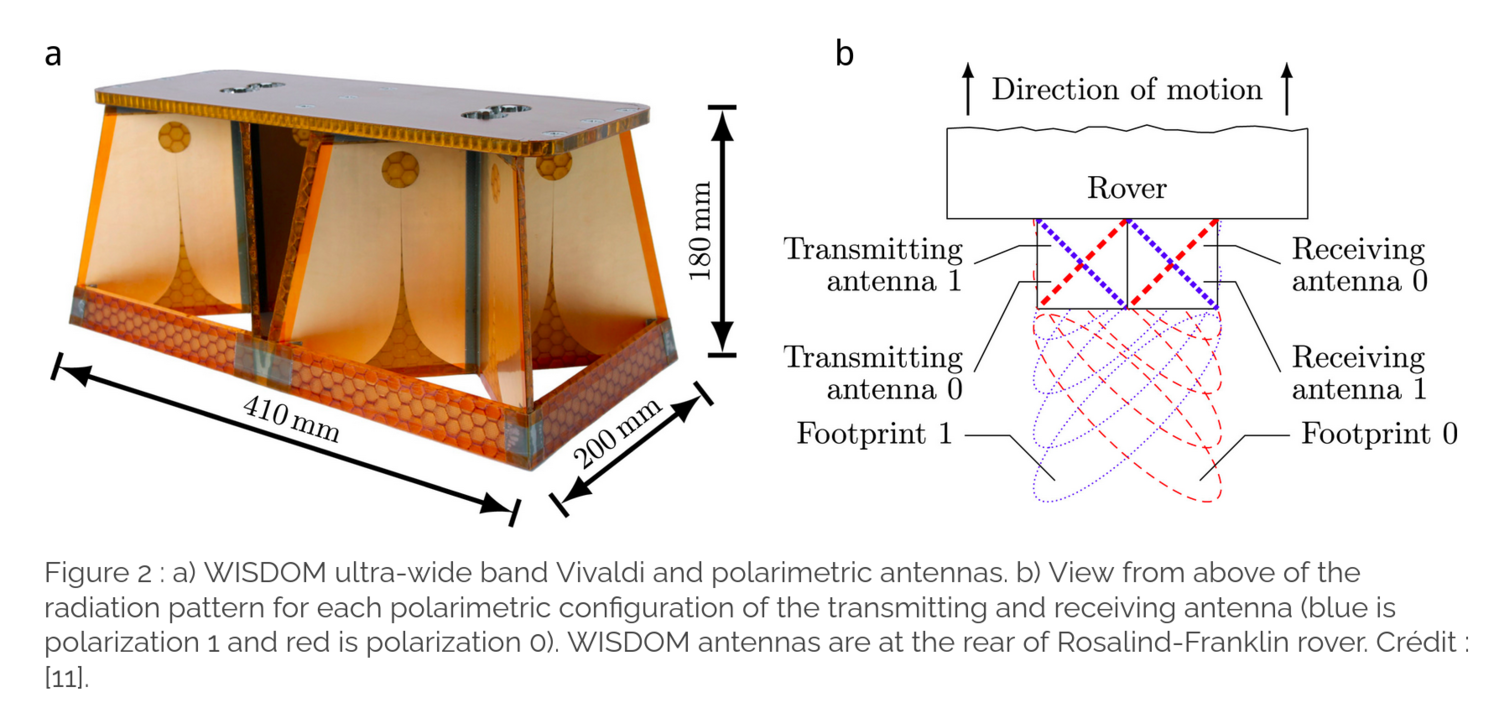

WISDOM data interpretation methods

The up-to-date WISDOM processing chain was applied to the data [7]. In addition, electromagnetic simulations were conducted to characterize the shape, dimensions and permittivity value of detected buried structures. Simulations are performed with TEMSI-FD, a 3D Finite Difference Time domain (FDTD) code [8] which can account for the actual radiation pattern of WISDOM antennas.

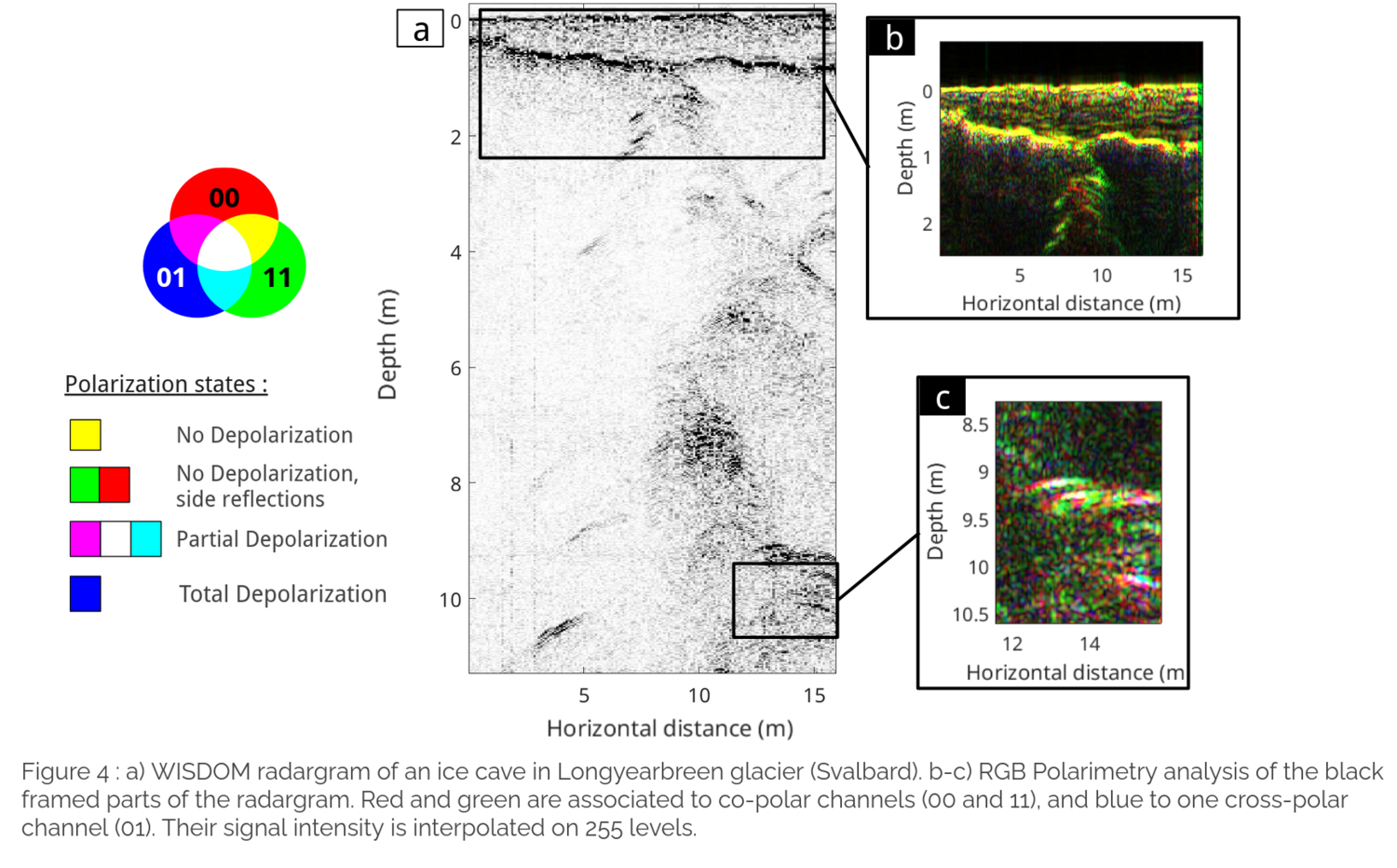

We also exploit the different polarization configuration measurements of WISDOM to constrain the geometry and the shape of detected targets. For instance, spherical targets have a low depolarisation efficiency whereas angular and corner reflectors are strongly depolarizing. Tilted interfaces change the direction of propagation of the waves as well as its polarization. To display the intensity in the different WISDOM polarimetric configurations, we produce additive RGB synthesis radargrams [7] by combining three of the four polarization configurations presented on Fig. 2. The different radiation patterns in polarization 0 and 1 (Fig. 2) allow to constrain the position of the red (only 00) and green (only 11) reflections to the right rear and left rear of the rover traverse respectively.

We use in a complementary way the Bandwidth Extrapolation (BWE) technique, a super-resolution method [9;10] which can improve the range resolution of WISDOM radargrams by a factor 3, allowing to meet the requirements of the ExoMars mission in materials of relatively low permittivity value.

Results

This section illustrates the use of simulations and polarimetric analysis on Svalbard data.

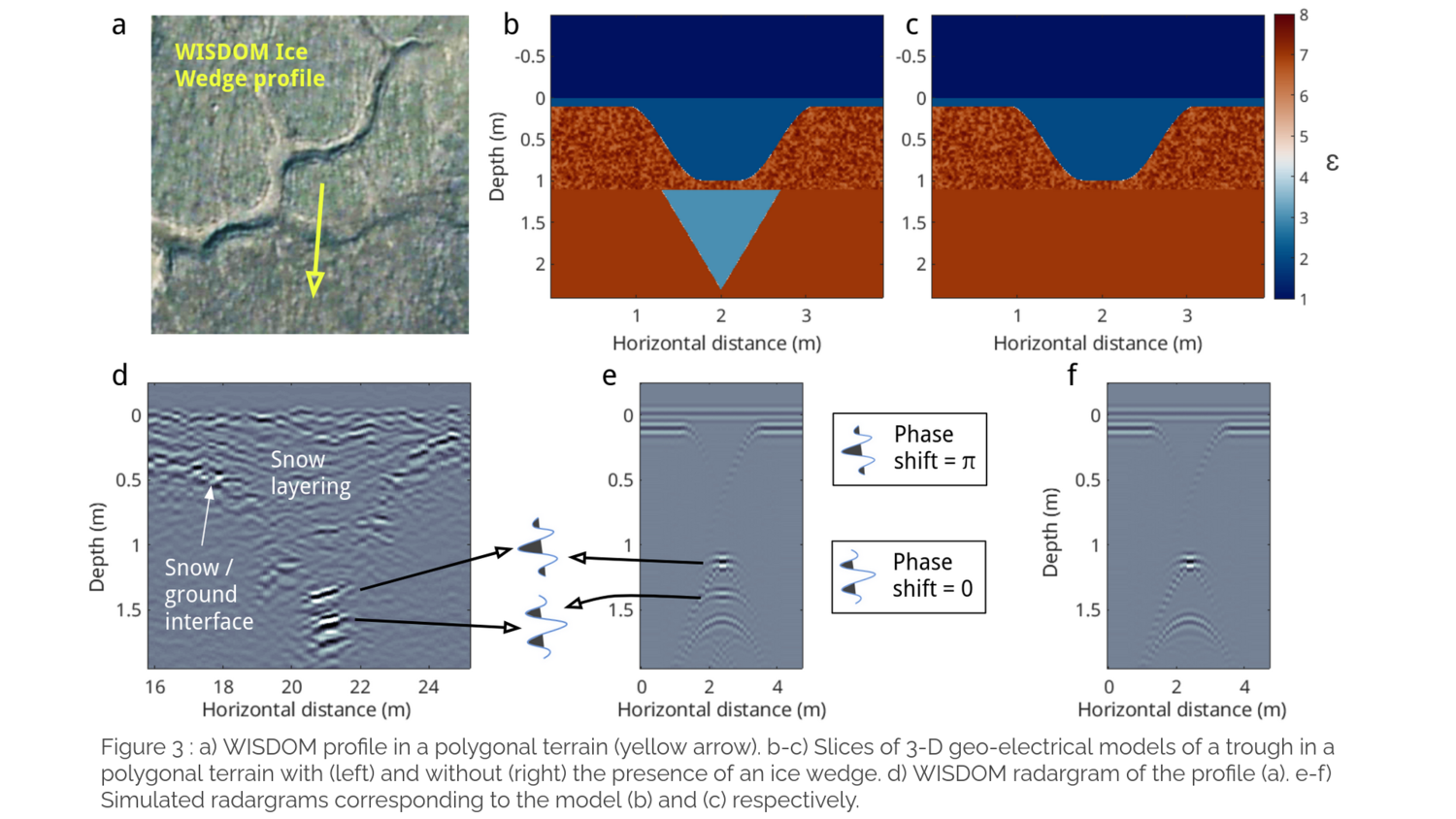

Contribution of 3D simulations to quantified interpretation

Fig. 3b and 3c present a vertical slice of a 3D geo-electrical model representative of the trough (with and without ice wedge underneath) separating two polygons in the polygonal terrain investigated with WISDOM (profile in yellow on Fig. 3a). Fig. 3e-f shows the corresponding simulated radargrams, which are compared to the experimental radargrams (Fig. 3d).

In both experimental and simulated data, snow/trough interface reflection weakens and disappears when the interface slope becomes too steep. The main contribution of these simulated radargrams is to remove ambiguity about the 3 intense reflections around 1.5 m deep. The middle reflection cannot be explained without the presence of an ice wedge, and the deepest signals are actually due to double reflections on the faces of the trough. The phase shift reported on Fig. 3d-3e supports the hypothesis that WISDOM waves travelled through a lower permittivity material, consistent with the presence of an ice body (ε=3.2) beneath the active layer material (ε≥7).

Polarimetric analysis of the data

The RGB display of the WISDOM radargram acquired above the ice cave of the glacier (Fig. 4a) reveals a variety of polarimetric signatures. Snow layers and snow/ice interface appear yellow (Fig. 4b) ; they are almost horizontal and relatively smooth, thus not depolarizing. From 1.5 to 2.5 m deep on Fig 4b reflections are either red or green; these structures are therefore off-track (not directly underneath the antennas). These features are nevertheless not depolarizing. In contrast, the received waves associated with the ice cave (Fig. 4c) are rather depolarized, meaning they may have experienced multiple reflections in the cavity.

Conclusion

The Svalbard data set allows to validate the WISDOM performances and the interpretation tools. The fine range resolution meets the mission’s requirements and the polarimetry constrains the position and shape or nature of buried reflectors, which is essential for the selection of the drill site. Simulations and polarimetry provide together quantified analysis of the subsurface structures, which will significantly contributes to the geological understanding of the site in synergy with the instruments of the payload. WISDOM will investigate the Martian subsurface in a complementary way to the lower frequency and non-polarimetric GPR RIMFAX and to RoPeR.

References

[1] C. Quantin-Nataf et al., Astrobiology, 2021

[2] F. Altieri et al., Advances in Space Research, 2023

[3] V. Ciarletti et al., Astrobiology, 2017

[4] A. Steele et al., AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, 2010

[5] M. Ulrich et al., Geomorphology, 2011

[6] N. Ross et al., Norwegian Journal of Geography, 2005

[7] Y. Herve, PhD Thesis, 2018

[8] C. Guiffaut et al., IEEE, 2012

[9] K.M. Cuomo, NASA STI/Recon Technical Report N, 1992

[10] N. Oudart et al., Planetary and Space Science, 2021

[11] W-S. Benedix et al., Planetary and Space Science, 2024

How to cite: Brighi, É., Ciarletti, V., Le Gall, A., Oudart, N., Hervé, Y., Plettemeier, D., Benedix, W.-S., Mas i Sanz, E., Shestov, A., Mercier, L., and Harrar, L.: Performance validation of WISDOM, the GPR of the ExoMars 2028 mission, on a Martian analogue dataset acquired in Svalbard, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-710, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-710, 2025.

Introduction: Polarimetric analysis of SAR imagery can provide extensive information about the scattering properties of an imaged surface. When looking at the Lunar South Pole, where the presence and abundance of ice has been debated for decades [1][2], having in-depth information about the present scattering mechanisms is invaluable. The Dual Frequency SAR (DFSAR) onboard ISRO’s Chandrayaan-2 provides fully polarimetric data in both L- and S-band, with the former expected to be able to penetrate up to 5m in dry, low loss soils [3]. With most of the subsurface ice expected to be located within the Permanently Shadowed Regions (PSR) of craters, the high-resolution coverage of these regions provided by Chandrayaan-2 allows the areas to be studied in greater detail.

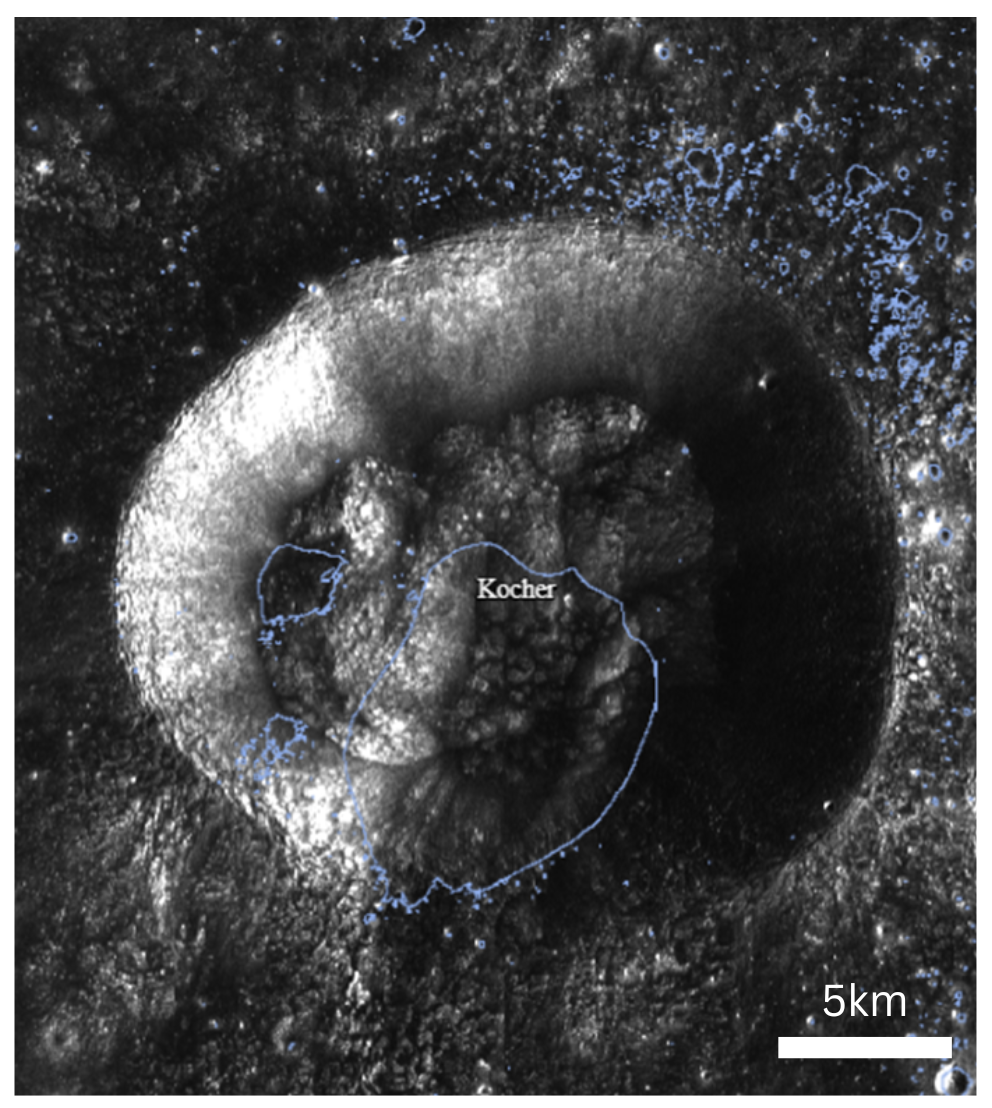

Study Region: Two craters, Kocher and Wiechert E, were selected for this study due to their anomalous nature – this meaning that the Circular Polarisation Ratio (CPR) of the crater is higher in the interior [4]. They both exhibit high backscatter returns around their rims, contain a PSR and have average temperatures lower than 100K. With Kocher having a diameter of >20km and Wiechert E having a diameter of <20km, their floor texture is an unusual characteristic, as often craters with a diameter greater than 20km are more complex and have features such as central peaks [5]. The radar-bright regions of the crater walls are a possible indicator of unique surface or subsurface materials.

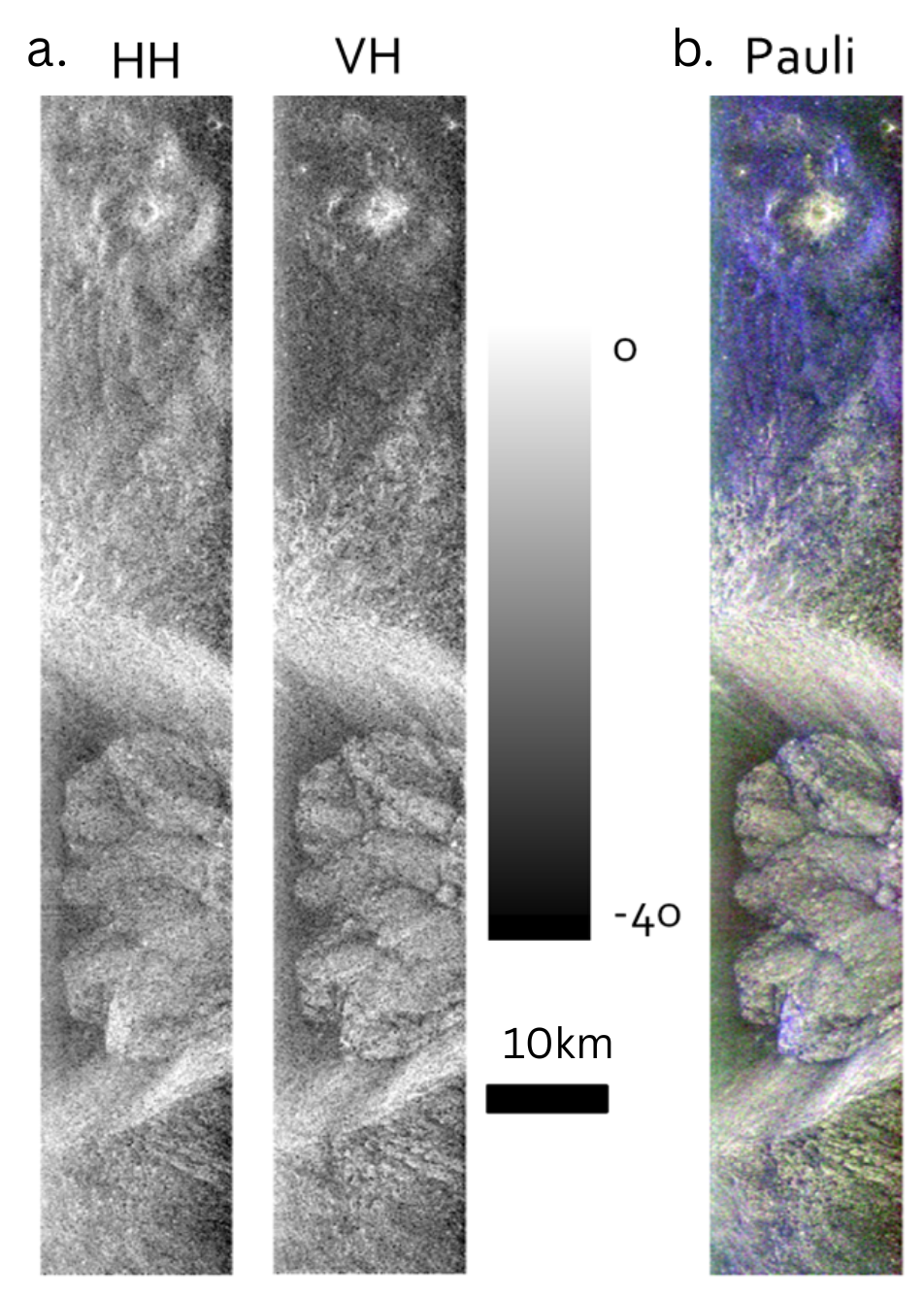

Methodology: Utilising bespoke code developed in python to detect and then radiometrically calibrate each polarisation to beta0 (HH, HV, VH, VV) as a baseline visualization, further code is used to extract the Coherency (T) matrix [6] and Pauli vectors to begin polarimetric analysis. Where H represents horizontal and V represents vertical, the Pauli vector k is defined by

This base-level decomposition can be utilised to differentiate between surface scattering from the first matrix component SHH + SVV, dihedral structure scattering from the matrix component SHH – SVV, and volumetric scattering with the final matrix component 2SVH.

Another technique used for in-depth analysis of the surface scattering mechanisms is the Claude-Pottier decomposition: a second-order optimisation method for distributed targets that provides information on the randomness of the scattering mechanism (entropy) and the potential dominant component. The scattering components of the Cloud-Pottier decomposition are derived from the 3x3 [T] matrix.

Initial Results: Kocher crater can be seen in Fig. 2, with the hummocky textured floor and large PSR represented in blue. The bright radar return from the western wall could be due to wavelength sized scatterers within the crater wall, but equally it is common for sloped terrain perpendicular to the look angle of the radar to appear bright. Since the Pauli Decomposition has high-level links to the physical scattering mechanism, we can map its components in colours (see Fig. 1b): the volumetric scattering is represented in green, while the surface scattering seen across most of the swath is represented in blue. The volumetric scattering component from natural mediascould be a representation of either subsurface ice suspended within the regolith or crustal material, or other wavelength sized scatterers such as larger rocks mixed into the Lunar regolith. Further analysis utilising the Claude-Pottier code to constrain the origin of the scattering mechanisms is being undertaken – including the possibility of distributed subsurface ice.

Fig. 1. (a) 5x5 Lee filtered HH and VH swath surrounding Kocher Crater (b) Pauli Decomposition of swath surrounding Kocher Crater.

Fig. 2. West-looking S-band image from LRO Mini-RF of Kocher. The outlined blue areas are the PSR. Image taken using LROC Quickmap.

Future Plans: A deeper investigation integrating the results from different decompositions and the backscatter of all polarisation channels is aimed to be completed for the surrounding areas of each crater. The plan is to then mosaic the swaths together once projected onto the ground and create full images of each crater for a complete study.

When completed, the code used for this project is planned to be released.

With NASA’s Artemis III mission landing areas planned to be around the South Pole, and many other space agencies and commercial companies sending missions to this region, understanding the geological context of the area is key to success, in particular the presence and accessibility of water ice.

Acknowledgments: We acknowledge the use of data from the Chandrayaan-II, second lunar mission of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), archived at the Indian Space Science Data Centre (ISSDC). UK Space Agency for funding this project; grant no. ST/Y005384/1 as part of the UK Government’s Science Bilateral Programme. LROC Quickmap team for hosting datasets and the map.

References: [1] Watson K. et al. (1961) J. Geophysical Research, 66, 9. [2] Campbell D. B. et al. (2006) Nature, 443, 835-837. [3] Bhiravarasu S. S. et al. (2021) Planet. Sci. J., 2, 134. [4] Spudis P. D. et al. (2013) JGR Planets, 118, 10. [5] French, B. M. (1998). LPI Cont. No 954, pp. 27. [6] Lee J. S. and Pottier E. (2017) CRC press.

How to cite: McVann, P., Ghail, R., Gallardo i Peres, G., Mason, P., Marino, A., and Knight, C.: Polarimetric Analysis of Anomalous Lunar South Pole Craters from Chandrayaan-2 DFSAR Data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1701, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1701, 2025.

Introduction: Understanding the subsurface structure is important for elucidating a planet’s geological evolution and thermal environment from its formation to the present. The Lunar Radar Sounder (LRS) onboard SELENE has detected buried regolith layers formed between subsurface lava flows [1]. While most radar surveys have focused on large-scale horizontal features (tens to hundreds of kilometers), (hundreds of meters to several kilometers) is gaining importance. Theoretically, lunar magma ascends due to buoyancy and volatile exsolution, and if it fails to erupt, gas voids can form at the magma tip [2]. Detecting such cavities would provide evidence of volatiles in lunar magma. In addition, lava tubes, which are potential habitats due to their thermal stability and radiation shielding, are key targets for future lunar exploration and base construction [3].

To detect small-scale subsurface echoes from LRS data, it is essential to accurately simulate the surface scattering from the lunar surface and to subtract this component from the LRS data. Kobayashi et al. (2020) simulated surface scattering using the Stratton–Chu integral method[4], but the resulting echo intensities were often higher than LRS observations at depths greater than 500 m, possibly due to artifacts in the SLDEM elevation model used.

In this study, we develop the detection method of small-scale subsurface echoes using LRS data and surface scattering simulation based on high-precision DEM generated by a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN). Furthermore, we analyze the spatial distribution of subsurface echoes and evaluate the subsurface structure indicated by the detected subsurface echoes.

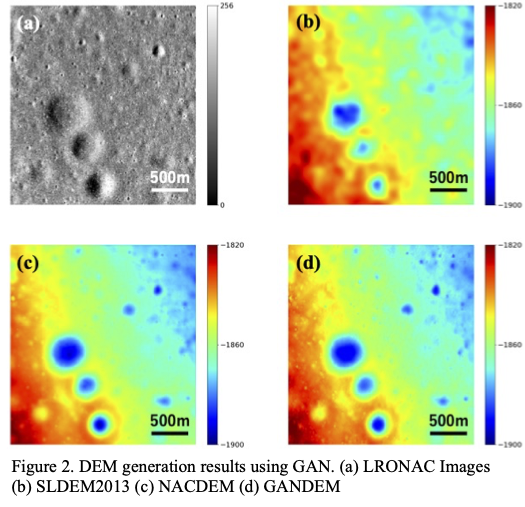

Methods: The analysis in this study consists of three steps: (1) generation of a high-resolution DEM using a GAN, (2) surface scattering simulation, and (3) detection of subsurface echoes. In the DEM generation phase, we construct a GAN model using high-resolution images (LRONAC images), a low-resolution DEM (SLDEM), and a high-resolution DEM (NACDEM). Then this trained model is then used to generate high-resolution DEMs (hereinafter GANDEM) by inputting SLDEM2015 and LRONAC images. In the surface scattering simulation phase, we calculate the electromagnetic field scattered from the lunar surface using GANDEM. The simulation is conducted based on the method proposed by Kobayashi et al. (2020) [4]. Finally, by comparing the simulated B-scans with LRS observations, we identify small-scale subsurface echoes. Figure 1 shows the overall process of the proposed approach.

Results: We generated GANDEM for the region of the Mare Tranquillitatis (latitude: 7°N-11°N , longitude: 31°E-34°E). Figure 2 shows the GAN-generated DEM (GANDEM) (Fig. 2(d)) for a portion of that region, as well as the corresponding LRONAC image (Fig. 2(a)) and SLDEM2013 (Fig. 2(b)) NACDEM (Fig. 2(c)). SLDEM2013 cannot reproduce crater shapes with diameters of less than approximately 100 m, compared to NACDEM (Figs 2(b) and 2(c)). On the other hand, GANDEM succeeds in expressing small craters at the same level as NACDEM (Figs 2(c) and 2(d)).

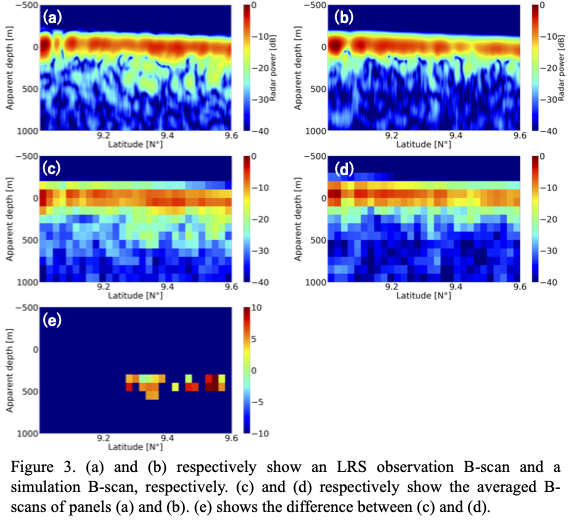

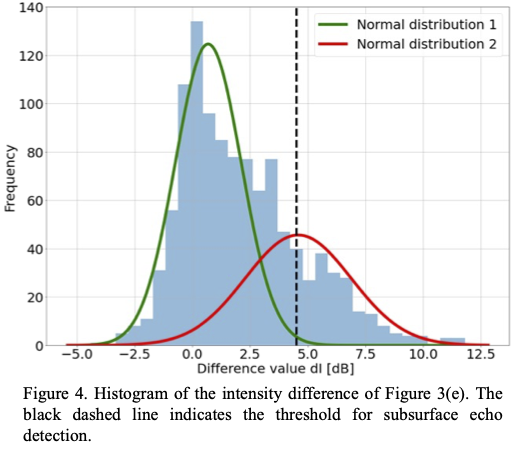

Using the GANDEM, we performed surface scattering simulations for LRS observation lines in the Mare Tranquillitatis. Figure 3 shows results from one representative track: (a) LRS observation radargram, (b) simulation result, (c) and (d) are their respective track-averaged radargrams, and (e) shows the pixel-wise intensity difference between (c) and (d). Figure 4 presents the histogram of intensity differences aggregated from 15 ground tracks in the region. A Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) was used to fit two distributions. The subsurface echo detection threshold was set at 3σ of the distribution centered near 0, corresponding to 4.50.

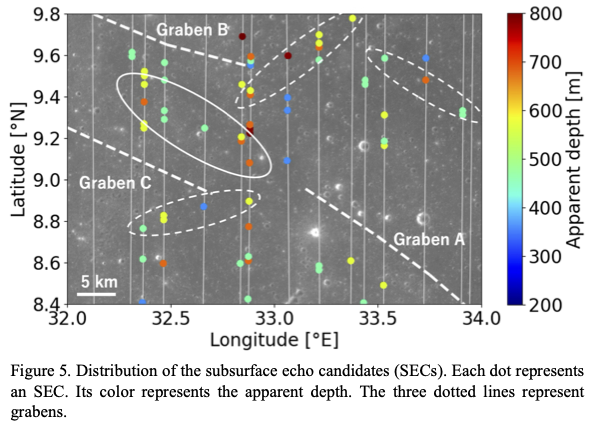

Figure 5 shows the distribution map of the extracted SECs. The color represents the apparent depth. The three dotted lines represent grabens, which are linear depression structures on the surface. SECs exist continuously on the northwest extension of graben A, shown by the white solid ellipse. In areas that were not extensional regions of the graben, some SECs were detected continually along multiple LRS ground tracks shown as white dotted ellipses.

Discussion: SECs have been observed along the northwestward extension of Graben A, which is likely formed by subsurface magma intrusion. These SECs may represent subsurface structures associated with the same intrusion. Additionally, SECs have been continuously detected along multiple LRS ground tracks in areas unrelated to grabens. This suggests the presence of other horizontally continuous subsurface features, such as lava tubes or magma-related voids.

We next consider alternative explanations for the observed SEC intensities and distributions. While echoes from regolith layers between lava flows have been reported in previous LRS studies [1], such layers would extend horizontally for hundreds of kilometers. This wide distribution cannot explain the continuous and linear distribution of SECs detected on the multiple LRS ground tracks in this study. Subsurface faults may return echoes stronger than –25 dB if their planes are oriented nearly perpendicular to the radar beam. However, with average lunar fault angles of ~60° [5], such reflections would occur in radargrams at depths of ~200 km—far deeper than the 350–800 m apparent depths observed for the SECs. Consequently, no fault could be the reflection source for the SECs. Layers of ice and liquid water returning strong radar echoes have been discovered under the surface of Mars [6], but those would not exist in the lunar equatorial region.

Therefore, more plausible subsurface structures indicating SEC detected along multiple LRS ground tracks are considered to be the exsistence of lava tubes or gas voids at magma tips.

References: [1] Ono et al. (2009) Science, 323.5916, 909-912. [2] Head and Wilson, (2017) Icarus, 283, 176–223. [3] Kaku et al., (2017) GRL, 44.20, 10-155. [4] Kobayashi et al., (2020) IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, 59.9, 7395-7418. [5] Golombek et al., (1979) Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 84.B9, 4657-4666 [6] Orosei et al., (2018) Science, 361, 490–493.

How to cite: Nozawa, H., Haruyama, J., Kumamoto, A., Toyokawa, K., Iwata, T., Head, J., and Orosei, R.: Small-Scale Subsurface Structure Detection using Lunar Radar Sounder and Surface Scattering Simulations Based on GAN-Generated DEM, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1128, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1128, 2025.

1. Introduction

Secondary craters result from the impact of primary ejecta falling back to the surface. Closer to the primary crater, secondaries form at low velocities and show asymmetric shapes (McEwen et al., 2005; Pike & Wilhelms, 1978; Oberbeck & Morrison, 1973; Melosh, 1989), while farther away, higher-velocity ejecta produce secondaries resembling small primaries (Bart & Melosh, 2007). This range-induced morphologic diversity creates a challenge in distinguishing simple primaries from distant secondaries, affecting crater-chronology accuracy (McEwen & Bierhaus, 2006).

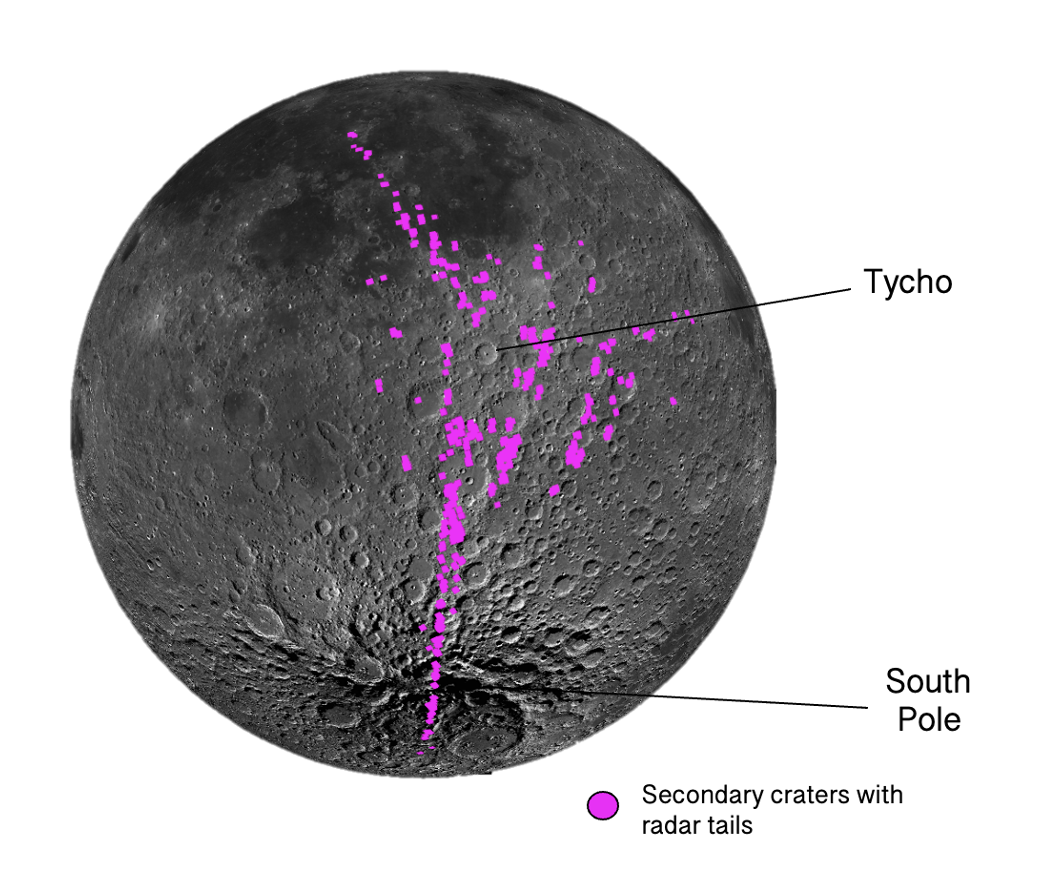

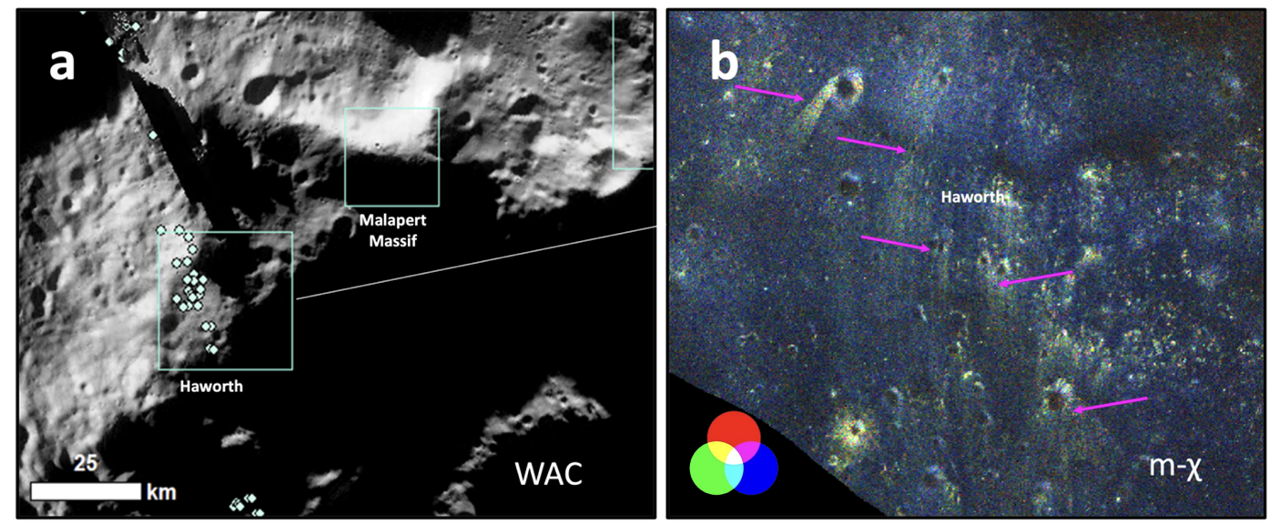

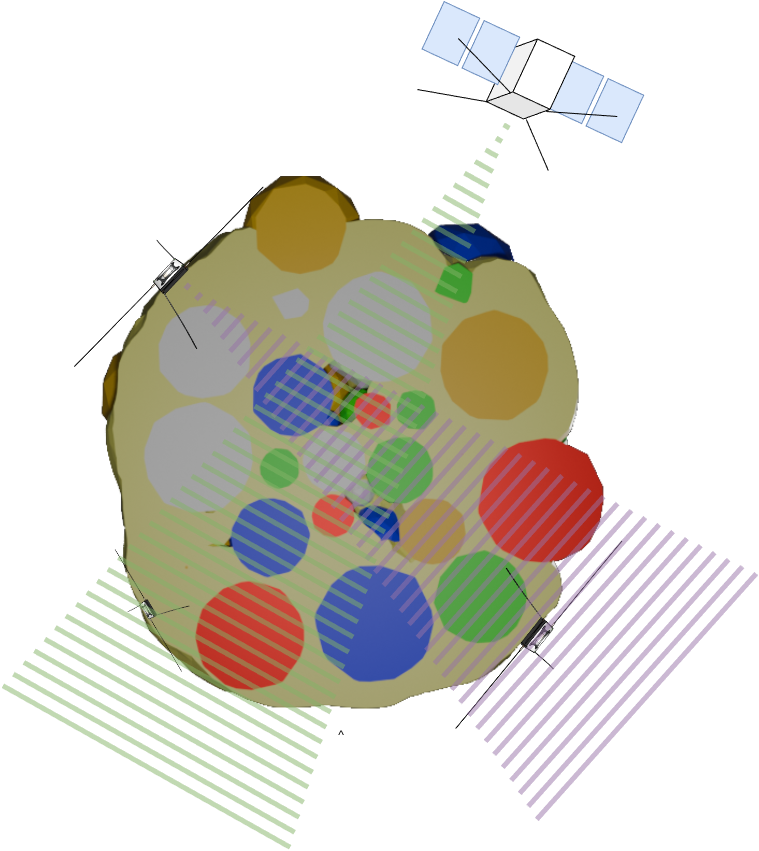

On the Moon, radar studies have found that some small craters exhibit radar-bright, asymmetric ejecta that is enhanced in cm- to dm-scale debris and may be attributed to secondary formation. Specifically, potential secondaries with ejecta extending downrange from Tycho crater have been identified within Tycho’s rays (Wells et al., 2010; Watters et al., 2017), including over the South Pole and intersecting Haworth, a potential Artemis landing site (Rivera-Valentín et al., 2024). Here, we used multiple datasets from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), including Mini-RF radar observations, to catalog and characterize Tycho secondaries along its rays. Our goal is to investigate the causes of these radar-bright, asymmetric ejecta deposits (termed “radar tails”) and explore their implications for secondary and ray formation processes.

2. Methods

Potential secondary craters along several of Tycho’s rays (Fig. 1) were first identified in radar imagery via the presence of a radar-bright, asymmetric ejecta signature oriented away from Tycho. We used S-band (12.6 cm) monostatic radar data from LRO Mini-RF, a hybrid-polarimetric SAR. Data products analyzed included circular polarization ratio (CPR) and m-chi decomposition images (Raney et al., 2012). The m-chi RGB composite displays even-bounce (red), random (green), and odd-bounce (blue) scattering.

Figure 1: Distribution of Tycho secondary craters with radar-bright extended asymmetric ejecta deposits (“radar tails”) identified in this study.

In addition to our radar characterization, we measured the depth and diameter for each potential secondary crater using LOLA elevation data (Barker et al., 2016) and calculated depth-to-diameter (d/D) ratios. The same method was applied to nearby primary craters (>300 m in diameter, without radar-bright ejecta tails) for context.

To study the morphology of secondary craters and understand the cause of the ejecta tails observed in the radar products, we then used both LROC NAC images and ShadowCam images to describe the surface texture of the radar tails and document the presence of boulders and assessed the maturity of the craters.

3. Results

We identified 473 craters in Tycho’s South Polar ray, including 24 secondaries at Haworth (Fig. 2, candidate landing site for the Artemis missions), and 543 more secondaries in the other bright rays. Tycho secondaries at Haworth could offer a chance to sample Tycho ejecta and compare it to Apollo 17 material (Jolliff et al., 2020; Rivera-Valentín et al., 2024).

Supporting our interpretation that the craters with radar tails are secondary craters is the observation that radar tail craters have lower d/D ratios (~0.04) than primaries (~0.10) identified in the same area. Preliminary crater size-frequency distribution analysis also supports this interpretation.

Figure 2: Tycho secondary craters with extended asymmetric ejecta (magenta arrows) in Haworth.

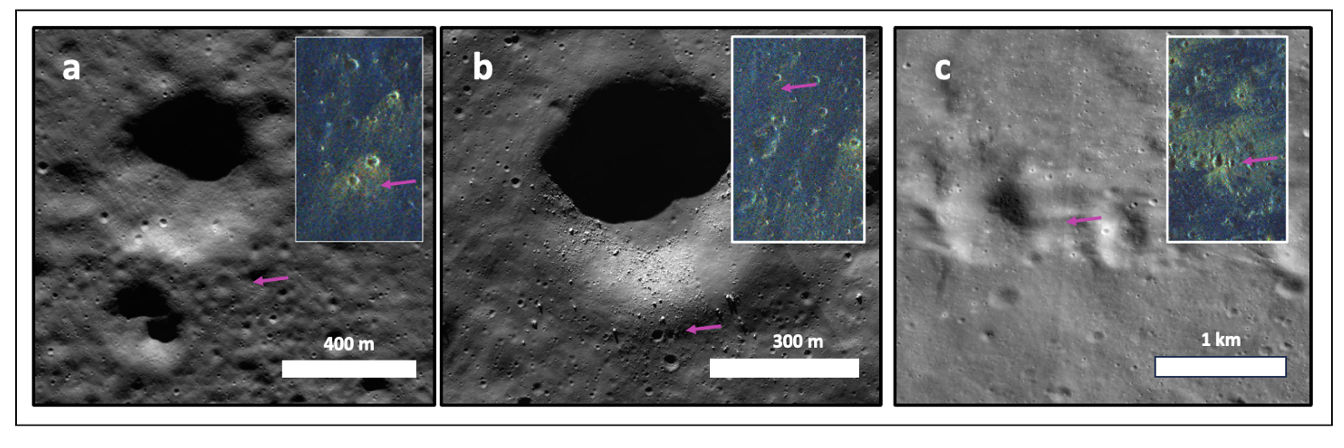

We find that Tycho secondary craters exhibit three possible classes of extended asymmetric ejecta: (1) isolated secondaries (only one radar-bright tail extends from the crater), (2) clusters (multiple tails merge into one emanating from a cluster of craters), and (3) linear crater chains (closely spaced craters arranged roughly straight line). We observed that the enhanced depolarized backscatter signals associated with the radar tails can be attributed to three main factors: (1) subsurface scattering likely caused by buried structures, such as subsurface blocky material or debris (based on the lack of observed surface features on visual images, (2) scattering from surface boulders, and (3) presence of craters (with D>200m) along the radar tail.

Figure 3: We found 3 main tail textures that could be causing the depolarized scattering (a) buried structures, (b) surface boulders, (c) additional craters.

4. Conclusions

We confirm that radar data can be used to identify fresh secondary craters on the Moon via the presence of extended, asymmetric radar-bright ejecta "tails" that trace surface roughness and subsurface scatterers. These tails, aligned with topography and pointing away from the primary impact site, may reflect ejecta debris flow processes, such as a debris surge (Campbell et al., 1992; Wells et al., 2010; Watters et al., 2017). Radar features often extend beyond visible surface textures, suggesting that much of the structure lies beneath the surface. Radar datasets are therefore uniquely placed to examine secondary processes.

References:

- Barker et al. (2016). Icarus, 273, 346–355.

- Bart and Melosh. (2007). Geophysical Research Letters, 34(7).

- Jolliff et al. (2020). 54th LPSC 2023 (LPI Contrib. No. 2806).

- McEwen & Bierhaus (2006). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 34, 535–567.

- Melosh (1989). Impact cratering: a geologic process. New York: Oxford University Press; Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Oberbeck et al. (1973). The Secondary Crater Herringbone Pattern, 4, 570.

- Pike & Wilhelms (1978). Secondary-Impact Craters on the Moon: Topographic Form and Geologic Process, 907–909.

- Raney et al. (2012). JGR: Planets, 117(E12).

- Rivera-Valentín et al. (2024). PSJ 5(4), 94

- Watters et al. (2017). JGR: Planets, 122(8), 1773–1800

- Wells et al. (2010), JGR: Planets, 115, E06008

- Martin-Wells et al. (2017). Icarus, 291, 176-191

How to cite: Perez-Cortes, S., Rivera-Valentin, E., Ahrens, C., Bramson, A., Fassett, C., Nypaver, C., Morgan, G., and Patterson, W.: Characterization of Tycho Secondary Craters on the Moon Using LRO Mini-RF Radar Data: Implications for Formation Mechanisms, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-861, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-861, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Introduction:

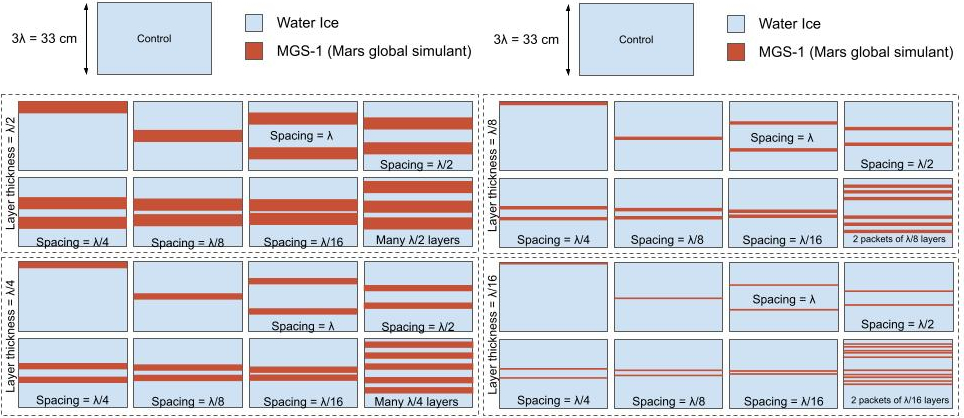

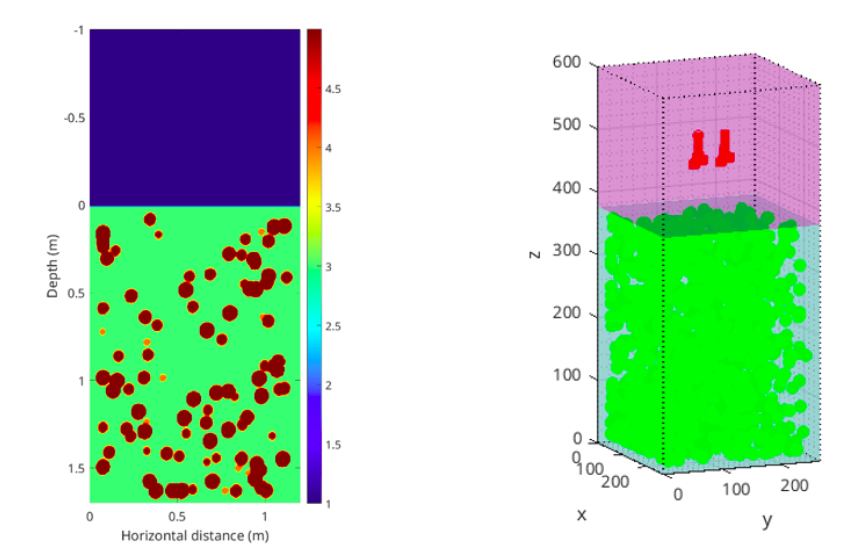

The Martian North Polar Layered Deposits (NPLD) are a kilometers-thick stack of icy layers, with a bulk composition of 95% water ice and the rest being silicate dust and lithics [1–2]. Individual layers within the NPLD vary in dust content, ranging from negligible amounts to potentially ~60% dust [3]. These differences are believed to be controlled by orbital forcing in Martian history, where each layer contains a snapshot of the paleoclimate at the time of deposition [4]. Specifically, it is believed that the large variations in Martian obliquity, ranging from ~15°– 60°, create alternating periods of ice accumulation and ice loss [5]. Our best tool to understand the layering within the entire vertical extent of the NPLD is orbital radar sounding, such as that from the Shallow Radar (SHARAD) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). However, visible imaging of exposures of the upper NPLD have shown that layers can have thicknesses down to decimeter to meter scales [6], smaller than SHARAD’s vertical resolution of ~10m. The impact that these sub-resolution layers have on radar observations is not completely understood [7–8], and it is hypothesized that a radar reflector within the NPLD may be the result of either a single relatively thick layer, or “packets” of thinly spaced layers [9]. Therefore, to understand the Martian paleoclimate recorded in the NPLD, we must have a better understanding of how different scales of layering influence the radar observations. To address this, we combine results from laboratory analog experiments and wave propagation simulations with Mars’ remote sensing observations.

Laboratory Setup:

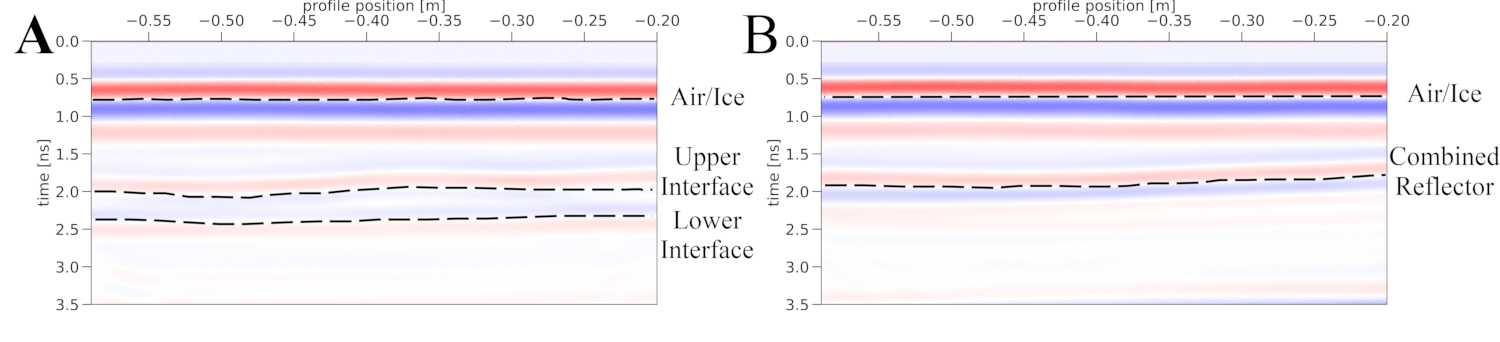

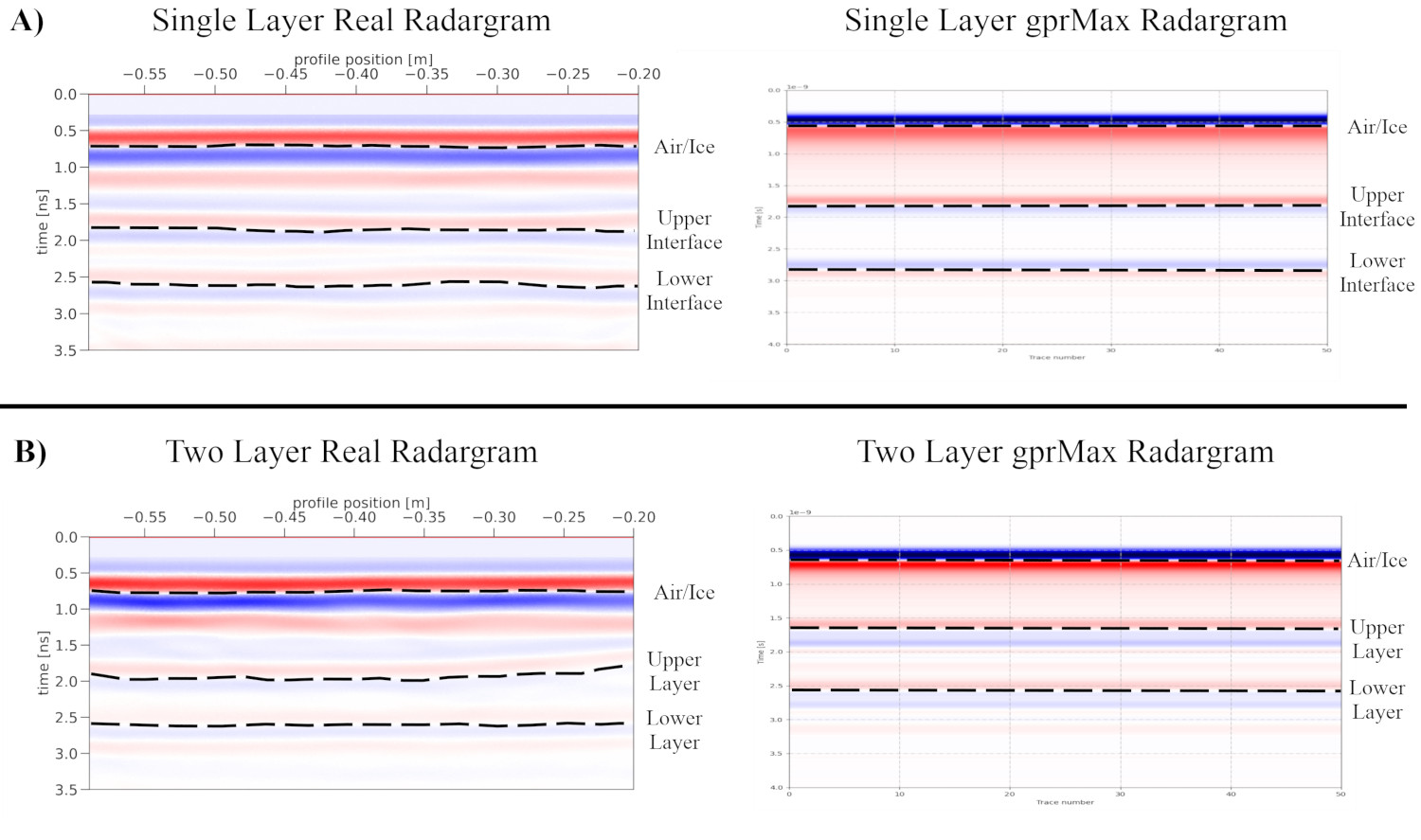

We create a series of laboratory analogs to test how radar observations are influenced by various sub-resolution layer thicknesses and spacings. Our radar measurements are made using a 2.7 GHz GSSI StructureScan Mini XT system, which is higher frequency than SHARAD but allows for experiments of a tractable size. Our experiments consist of different configurations (Fig. 1) of 100% water ice layers and dust-rich layers composed of ~55% Martian regolith simulant MGS-1 [10] and ~45% ice, within a 72cm × 72cm × 45cm polyethylene container housed in a -20°C freezer. These experiments focus on dusty layer thicknesses and spacings ranging from λ/2 to λ/16 (where λ is the wavelength of the transmitted radar wave in free space, 11 cm for 2.7 GHz).

Fig. 1 Example of various dusty layer configurations to be tested. Experiments are conducted in a 72cm × 72cm × 45cm polyethylene container and radar data is collected using a commercial radar system with a center frequency of 2.7GHz (free space λ ≈ 11cm).

Preliminary Results:

Current results indicate that the critical thickness for a single dusty layer to have distinct upper and lower reflectors in our NPLD analog experiments is > λ/8, which matches theoretical expectations [7]. Fig. 2 shows radargrams for a single λ/4 thick dusty layer, where upper and lower reflectors are distinct, and a single λ/8 dusty layer, where the upper and lower reflectors are combined into one reflector. Based on early results, coarsely spaced layer packets may be differentiated from singular thick dusty layers based on total power returned from the lowest reflector. In Fig. 3, a singular λ/2 thick dusty layer has reduced power returned from the reflector corresponding to the bottom of the layer, compared to that from a layer packet configured with two λ/8 thick dusty layers, spaced λ/2 apart. Combining these initial results with more experiments and simulations to extrapolate results to larger scales and lower frequencies will establish a guideline to interpreting SHARAD data of the NPLD.

Fig. 2 A) Radargram of a single λ/4 (2.75 cm) thick dusty layer. Upper and lower contacts with the ice show distinct separate reflectors. B) Radargram of a single λ/8 (1.375 cm) thick dusty layer. Upper and lower contacts do not show distinct reflectors and combine into one reflector.

Fig. 3 Comparison of radar power returned for two experimental configurations: a single, thick (λ/2; 5.5cm) dusty layer and two thinner (λ/8; 1.375 cm) dusty layers spaced λ/2 (5.5cm) apart. Left side of each subpanel illustrates the stratigraphic configuration (centered on the depth of the middle of the experimental column), with dusty layers in orange and water ice in light blue. Right side of subpanels shows radar power (relative to transmitted power) returned for detected interfaces associated with the layer(s).

Future Work:

More experiments will be run, as shown in Fig. 1, to better understand how the power return of reflectors changes with thickness and spacings. Additionally, experiments focused on packets of λ/8 thick layers at increasingly thinner spacings will be conducted, to understand when layer packets appear as a singular layer in radar data. We are also running simulations of these experiments using two Finite-Difference Time-Domain based electromagnetic wave propagation softwares, gprMax [11] and Remcom’s XFdtd to allow us to relate our empirical laboratory results to theoretical results. For example, in Fig. 4, we show our measured experimental radargrams compared to preliminary simulations of waveform propagation for the same configuration. We will apply these laboratory results and simulations to apply our findings to SHARAD data and place new constraints on layer properties of the NPLD.

Fig. 4 Comparison of experimentally measured radargrams (left) and gprMax simulations (right). A) Results for the configuration of a single, thick (λ/2; 5.5cm) dusty layer. B) Results for the configuration of two thinner (λ/8; 1.375 cm) dusty layers, spaced λ/2 (5.5 cm) apart.

References:

[1] Malin (1986) Geophys. Res. Lett., 13(5), 444–447. [2] Sinha & Horgan (2022) Geophys. Res. Lett., 49(8). [3] Lalich et al. (2019) JGR Planets, 124(7), 1690–1703. [4] Byrne (2009) Ann. Rev. of Earth and Planet Sciences, 37, 535–560. [5] Montmessin (2006) Space Sci. Rev., 125 (1–4), 457–472. [6] Herkenhoff et al. (2007) Science, 317, 1711–1715. [7] Widess (1973) Geophysics. 38(6), 1176-1180. [8] Zeng (2009) Leading Edge. 28(10), 1192-1197. [9] Putzig et al. (2009) Icarus, 204, 443–457. [10] Cannon et al. (2019) Icarus, 317, 470–478. [11] Warren et al. (2016) Computer Phys. Comms., 209, 163–170.

How to cite: Harris, S., Bramson, A., and McGlasson, R.: Effects of thin layers on radar observations of the Martian polar layered deposits: An integrated approach using experiments, simulations, and spacecraft observations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1086, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1086, 2025.

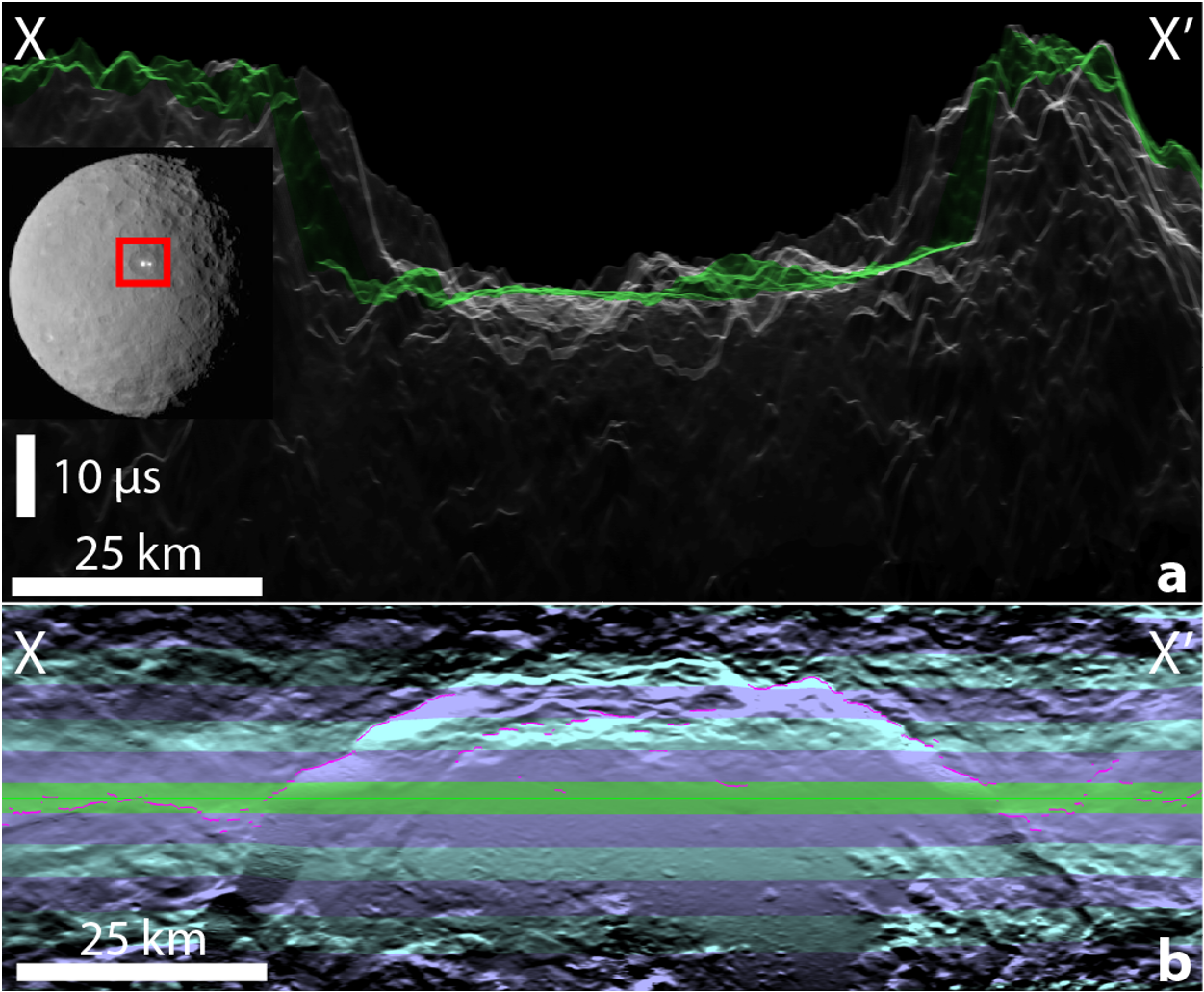

Introduction: The Radio Echo Sounding (RES) technique is commonly used on Earth to study the internal structure of ice sheets and understand ice flow (e.g., [1], [2]). Although large ice caps also exist at the Martian poles, their internal deformation and flow dynamics remain largely unknown. This study presents radar data from the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS; [3], [4]) at Ultimi Scopuli on Mars (Fig. 1A, B), revealing the radar first evidence of large-scale englacial folds within the South Polar Layered Deposits (SPLD). These features are similar to those found in Earth's ice sheets, indicating that the Martian ice sheet has experienced movement under either dry or wet basal conditions.

Results: The radar sections collected at US (Fig. 1C) exhibit a general stratified ice structure, typically ~1500-2500 m thick, overlying a flat/slightly rough sub-horizontal bedrock (at MARSIS resolution). The ice stratigraphy is generally characterized by sub-horizontal and continuous or gently undulated and disrupted reflection horizons that are roughly equally divided in two principals radar units by a semi-continuous and sub-horizontal sharp and thick radar reflector (labelled “H1” in figures). In some cases, the radar horizons are locally slightly inclined and truncated by the H1, suggesting an unconformable discontinuity surface. The lower unit (labelled “U1” in figures) is ~700-1200 m thick and is mostly characterized by low radar reflectivity with few relatively thick and fuzzy internal reflection horizons. On the contrary, the upper unit (labelled “U2” in figures) is ~800-1200 m thick and mainly composed by a thinly stratified radar sequence with bright reflectors.

Observing the MARSIS radargrams (i.e., Fig. 2), in its interior the ice sheet layering is locally interrupted and disrupted by clear radar dark-areas of non-reflective ice (from now on “Non-Reflective Areas” or “NRA”). However, in their inner core, the NRAs sometimes show bright-toned and rounded/elliptical layering (“eye-folds” like structures”) and “anti-form” like folding. Some other folding can partially envelop the dark NRAs or are located near such structures. In general, the NRAs have an irregular rounded to elliptical shape and usually develop from the interface between the bedrock and the base of the icy mass. On average, surveyed NRAs are ~16 km long and several hundreds of meters thick (up to ~1500 m), thus they are markedly elongated along the horizontal x-axis. All the above-described radar features are mainly present in the basal unit (U1), below the depth of ~700-1000 meters (i.e., below the H1 horizon); nevertheless, in some cases (e.g., Figs. 3, S1 and S3) deformation structures appear to interrupt or to be upon the H1 horizon, partially involving the upper sequence (U2), however always lying below ~500 meters in depth from surface.

Discussion and Conclusions: In terrestrial ice sheets, highly deformed layers linked to areas of high dynamic ice flow driven by variation in basal shear stress typically cause strong power loss in internal reflectors of ice-penetrating radars (e.g., [5], [6]). In RES images, these zones tend to be dark (i.e., “layer free”) and interrupt the lateral continuity of the horizons from the bedrock up to some depth since internal layering slopes are most extreme near the ice bed (it is exhibited strong deformation) and thus power loss intensify at depth [5]. In such circumstances, the lossy/diminished radar power areas can be bordered by bright folded reflectors/undefined areas [1], [7], [8] and can include folded bright reflectors in their core as well. All these radar structures are the signature of broad asymmetric/complex geological shear folds, characterized by one limb steeper than the other [5] and/or completely tilted and classified as overturned/recumbent and sheath folds (e.g., [1], [7, [8]).

Net of the unavoidable approximations due to the different frequency and resolution of the radar instruments, we compared the main NRAs radar features detected by MARSIS at US with some examples of the above described englacial structures observed by RES in Greenland and Antarctica polar ice sheets (e.g., Fig. 3 after [1], [7], [8]). The data matching points out their consistency in terms of radar morphology and morphometry, and the most plausible interpretation is that large-scale geologic folds are affecting the SPLD stratigraphic architecture of US ice-sheet. In particular, considering the overall setting of the main surveyed structures, the MARSIS dark NRAs and the deformed radar patterns in U1 unit seem to be consistent with the englacial sheath folds known on Earth. The existence of sheath folds states that large displacements have occurred in the US region due to ice-flow/basal sliding, similarly to what observed in the SPLD in Promethei Lingula by previous studies [12]. On Earth, the origin of large englacial folds is still debated, with various dry or wet mechanisms proposed. Several mechanisms (dry or wet) have been proposed since now, often depending on case to case (e.g., [1], [9], [13]). Understanding similar Martian structures is harder due to limited data, environmental knowledge, and structural analysis. Ongoing studies aim to shed light on all these aspects.

References: doi: https://10.1002/2014JF003215. [2] doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/aog.2020.11. [3] doi: https://10.1016/j.pss.2009.09.016. [4] Picardi G. et al. (2004) in Mars Express: The Scientific Payload, ESA SP-1240. [5] doi: https://10.3189/2014AoG67A005. [6] doi: https://10.5194/essd-14-763-2022. [7] doi: https://10.1002/2014GL062248. [8] doi: https://10.1002/2015JF003698. [9] doi: https://10.1016/j.jsg.2015.09.003 [10] doi: https://10.1016/j.jsg.2006.05.005. [11] doi: https://10.1111/j.1365-3121.2012.01081.x. [12] doi: https://10.1016/j.icarus.2012.06.023. [13] doi: https://10.1016/j.epsl.2015.10.024.

Acknowledgements: This research was supported by the Next Generation EU program, Mission 4, Component 1, through project “Combining mAchine Learning and optImization for Planetary remote Sensing missiOns” (CALIPSO), Unique Project Code C53D23010010001.

Fig. 1. MOLA location and MARSIS radargrams

Fig. 2. Examples of “NRAs” and englacial folding (“eye-folds” -EF- and “anti-form” -SF- folding like structures) in MARSIS radargrams.

Fig. 3. Example of folding in RES (Greenland) compared with MARSIS structures. Image after Figure 13 in [1] © AGU-Wiley.

How to cite: Guallini, L., Orosei, R., and Pettinelli, E.: First Evidence of Large-Scale Englacial Folding in the South Polar Layered Deposits (Ultimi Scopuli, Mars) Unveiled by MARSIS, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-72, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-72, 2025.

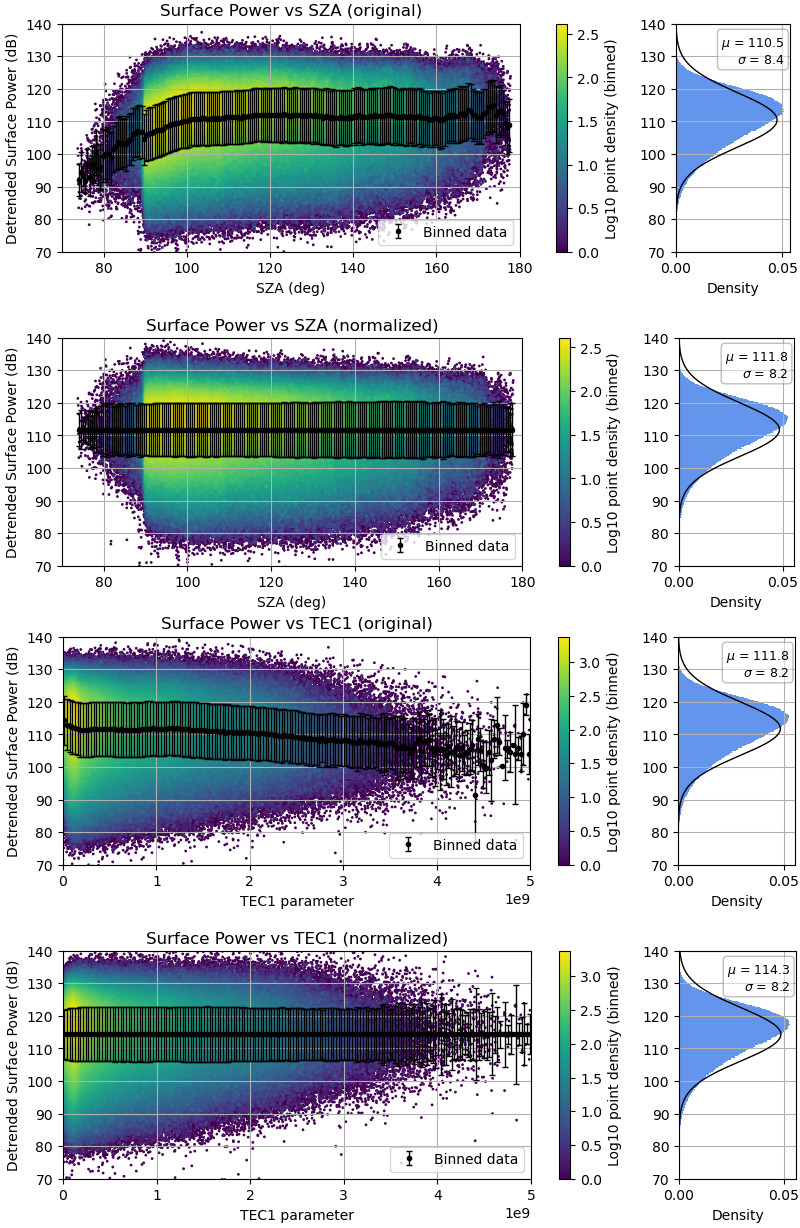

Introduction: One of the main goals of Mars science and exploration is to explore the shallow subsurface (i.e., 10s-100s meters) and reveal its geologic nature and composition [1]. Although many remote sensing techniques can probe the subsurface, there is currently a sensing gap at depths between ~1 and 100s of meters. Radar surface reflectivity analyses can fill this gap thanks to sensitivity to changes in composition and geologic structures at ~5-15 m depth with the Shallow Radar (SHARAD, [2, 3]) and ~50-150 m depth with the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS, [4, 5]). Historically, MARSIS surface reflectivity analyses were limited by insufficient coverage and ionospheric effects, which caused attenuation and distortion of the radar echoes. Thanks to new processing techniques and nearly global coverage after continuing MARSIS observations for nearly 20 years [6], it is now possible to probe the Martian near-subsurface at four distinct frequencies ranging from 1.3 MHz to 5.5 MHz.

Methods: We employ a recently released PDS MARSIS dataset that corrects ionospheric phase distortions and provides three empirical parameters associated with ionospheric total electron content (TEC), in turn related to radar echo delay and attenuation [7, 8]. MARSIS operates at four distinct frequency bands, centered at 1.8, 3, 4, and 5 MHz, each with 1 MHz bandwidth, resulting in a free space vertical resolution of 150 m. This allows us to construct four reflectivity maps, each corresponding to a MARSIS band and probing to larger depths as frequency decreases. We process the surface echo power for each frequency through the following steps:

-

Automatic picking of surface echoes based on global topography and “clutter” simulations [9].

-

Path loss correction to account for surface echo power changes due to spacecraft altitude.

-

Ionospheric loss correction via normalization of surface power with respect to solar zenith angle (SZA) and the three TEC parameters (example in Fig. 1).

-

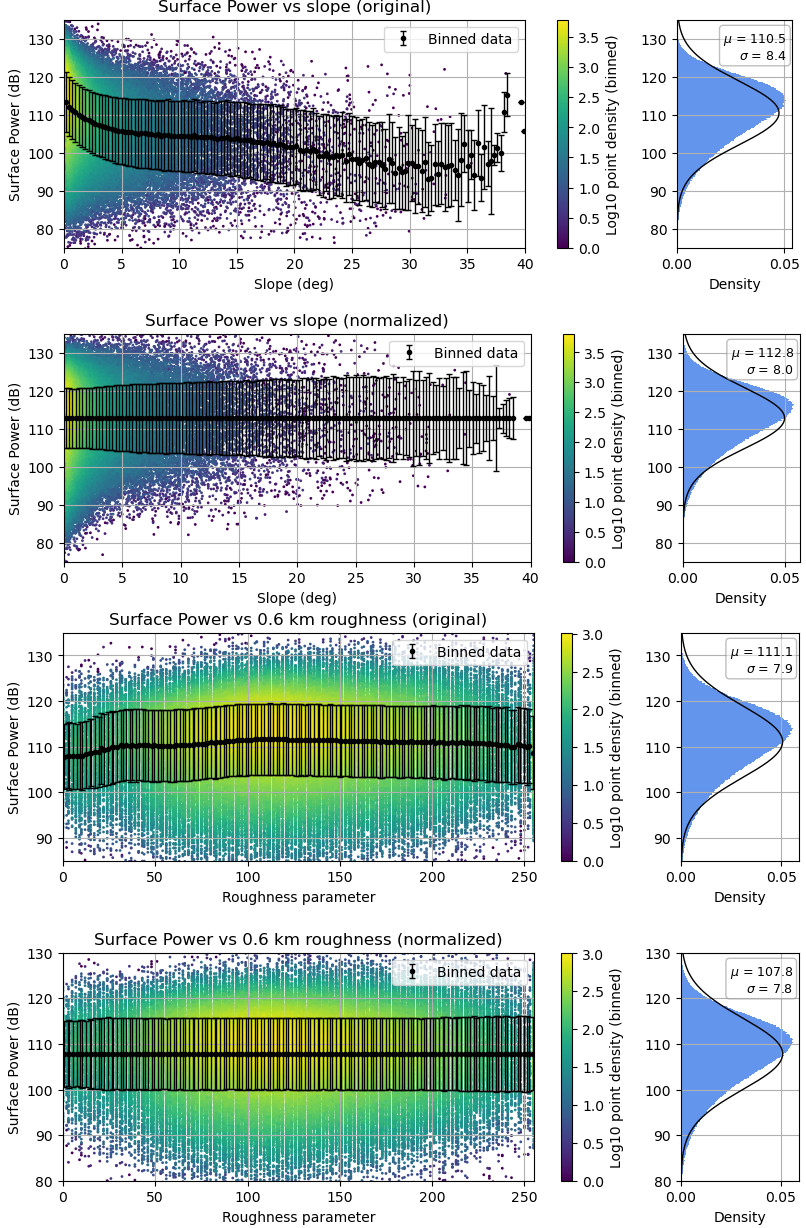

Removal of surface geometry effects via normalization of surface power with respect to slope measured from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA, [10]) 463 m/pixel global DEM and surface roughness calculated at 0.6 km, 2.4 km, and 19.2 km baselines from [11] (example in Fig. 2).

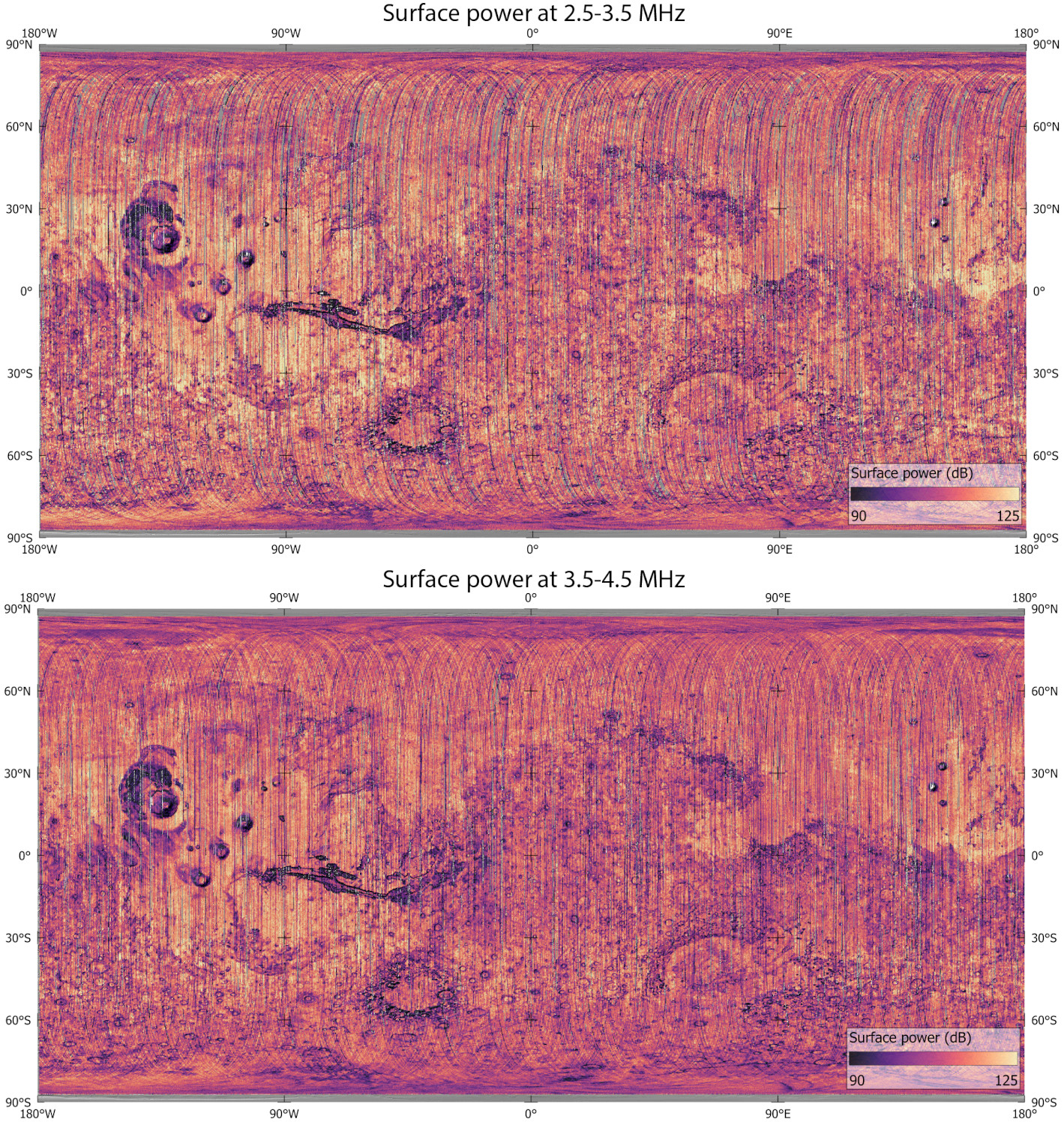

Finally, we generate surface reflectivity maps for each MARSIS band by gridding corrected power values at 5 km/pixel resolution and accounting for the variable footprint of each echo, measured as the radius of the 1st Fresnel zone.

Figure 1: Example of ionospheric effect corrections based on SZA (top) and TEC1 parameter (bottom) applied to the 3 MHz surface echo power data.

Figure 2: Example of surface geometry corrections based on slope (463 m/pixel) and roughness (at 0.6 km baseline, [11]) applied to the 3 MHz surface echo power data.

Results: We find a strong surface echo power dependence on the local SZA (Fig. 1), with lower frequencies experiencing loss at higher SZA values, an expected behavior for MARSIS [5, 8]. After applying the SZA correction, we still find a non-linear dependence on all TEC parameters (Fig. 1), showing that up to 3-4 dB of loss occurs even at low TEC values. There is also a significant dependence on slope and 0.6 km baseline roughness (Fig. 2), suggesting that MARSIS echo power is most susceptible to short wavelength roughness.

Figure 3: Preliminary MARSIS surface reflectivity maps at the 3 and 4 MHz bands, plotted on MOLA shaded relief.

After empirical correction, the preliminary surface reflectivity maps (examples in Fig. 3) reveal several prominent features, such as high surface reflectivity associated with lava flows in Tharsis and the Elysium/Amazonis Planitiae, and low reflectivity zones corresponding to the friable Medusae Fossae Formation. The Martian northern plains reveal a wide range of reflectivity likely associated with variable terrain types including ice-rich deposits [12, 13] and the latitude-dependent mantle [14].

Discussion: The consistency of surface power measured across adjacent profiles in our preliminary maps indicates that the correction of path and ionospheric losses is effective at all SZA values, thus eliminating the need for filtering. Despite the low number of observations and significant ionospheric losses, we also obtained the first Mars surface reflectivity map at 1.3-2.3 MHz.

There is a weak residual surface power dependence on roughness, likely due to simplifications in our preliminary approach. To address this, we are currently running a detailed analysis of several roughness and slope parameters within the 1st Fresnel zone of each MARSIS echo, leveraging the entire MOLA shot point dataset [10]. This will allow us to capture the effects of short wavelength roughness highlighted by the preliminary results at 0.6 km baseline (Fig. 2).

All reflectivity maps show enigmatic “sinuous stripes” across the southern highlands with low power values compared to surrounding areas. These features are consistent across adjacent profiles and their location and shape resemble ionospheric anomalies associated with remnant crustal magnetization observed by SHARAD [15]. A simple empirical correction based on the total crustal magnetic field [17] appears to remove most of these features, suggesting that MARSIS is particularly sensitive to ionospheric phenomena linked to crustal magnetization. We will further test this hypothesis via analyses of TEC parameters and magnetic anomaly data.

Overall, these results offer new insights into volcanic, sedimentary, and ice-related processes. They also lay the groundwork for future missions targeting subsurface ice or landing sites.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by NASA MDAP grant 80NSSC22K1079.

References: [1] MEPAG Science Goals document. [2] Campbell et al. (2013)JGR: Planets. [3] Seu et al. (2007)JGR: Planets. [4] Mouginot et al. (2010)Icarus. [5] Jordan et al. (2009)PSS. [6] Orosei et al. (2015)PSS. [7] McMichael et al. (2017)2017 IEEE RadarConf. [8] Plaut (2024)Optimized MARSIS PDS4 release. [9] Choudary et al.(2016)IEEE GRSL. [10] Smith et al. (2001)JGR: Planets. [11] Kreslavsky and Head (2000)JGR: Planets. [12] Bramson et al. (2015)GRL. [13] Stuurman et al. (2016)GRL. [14] Kreslavsky and Head (2002)GRL. [15] Campbell et al. (2024)GRL. [16] Campbell and Morgan (2018)GRL. [17] Langlais et al. (2019)JGR: Planets.

How to cite: Nerozzi, S., Christoffersen, M., Morgan, G., Grima, C., and Plaut, J.: Measuring the Mars Global Surface Reflectivity at 1.3-5.5 MHz with MARSIS, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1857, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1857, 2025.

MARSIS radar onboard MEX did numerous observations of Phobos the past 20 years, trying to highlight geological structures in the Phobos subsurface. Up to now, these measurements never allowed us to identify subsurface features while the onboard software upgrade in 2023 promises a significant sensitivity improvement. On the other hand, a deeper analysis demonstrated a deviation between the orbit prediction and the ranging measurements done by MARSIS and then allowed us to derive a new constraint for Phobos ephemeris calculation.

Phobos’ orbit is currently known down to a precision of 300m, mostly directed along its track. It has mainly been determined with imagery, and more recently with the Super Resolution Channel of the HRSC camera onboard Mars Express (MEX). This method is associated with an error mainly normal to the plane of imagery. By dynamical constraints, Phobos’ trajectory determination error is mainly spread along its orbit.

In order to refine the orbitography and reduce the range error of the measurements, we propose to use data from the MARSIS (Desage, 2024). To do so, we perform a SAR synthesis on the MARSIS data in order to locate the radar echoes in a range/along-track plane. For every one of the 35 datasets at our disposal measured between 2008 and 2021, we also perform a coherent simulation using a Phobos shape model by Willner et al. (2014), and apply the SAR synthesis the same way we did for the MARSIS datasets. Given the geometry of our simulations and the SAR synthesis, the simulated radargrams are not sensitive to a range error of a few km in MEX’s trajectory, they can therefore be taken as reference points. We measure range errors between simulations and MARSIS data, distributed around +1km, with a standard deviation of 350m. The measurements being spread all around Phobos, the most probable cause for the non-zero average of the offsets measurements is an instrumental delay. After subtracting this average from the measurements, we estimate the offset of Phobos along its track that would create this standard deviation.

We find that this offset is of about 100m before 2017, and that the estimated value is rising linearly after this date to reach about 1.3km in 2021, date of our last observation. Since 2017 is the date of the last control point of the NOE-4-2020 ephemeris used for this study, our measurements exhibit a significant drift after this time. The systematic analysis of MARSIS data set from 2007 to 2021 is available in Desage, 2024 and was taken into account in the last Phobos ephemerid (V. Lainey, 2024, NOE-4-2024-MMX-D3). The possibility of a joint Radio-Science and MARSIS observation is also under evaluation to better constrain Phobos distances during Radio Science measurement and then improve gravity field measurement.

How to cite: Herique, A., Desage, L., Lainey, V., Kofman, W., Cicchetti, A., Orosei, R., and Andert, T.: MARSIS data as a New Constraint for Phobos’ orbit , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-286, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-286, 2025.

Mechanisms hypothesized for the formation of notable geologic features on Europa (e.g., chaos terrains) can alter the surrounding icy regolith to depths of a few meters to tens of meters (i.e., the near-surface) [1]. On Ganymede, variations in bulk composition and porosity may exist across the surface indicative of impact erosion and mass wasting processes [2]. The ability to characterize these compositional and physical properties (e.g., porosity), particularly in the context of its surface geology, provides a window into processes governing the evolution of their icy regoliths, both spatially and with depth.

The application of radar reflectometry to study the ‘surface’ return from sounders has been demonstrated to be a promising technique for characterizing near-surface ice on Earth and Mars [3, 4]. Such an approach can also be applied to future observations from the Europa Clipper and JUICE missions, both currently en route to the Jovian system. Both missions host nadir-pointing ice-penetrating radars: the Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (REASON) on Europa Clipper [5] transmitting simultaneously at center frequencies of 60 MHz and 9 MHz, with bandwidths of 10 MHz and 1 MHz, respectively, and the Radar for Icy Moons Exploration (RIME) on JUICE [6] at 9 MHz center frequency with a bandwidth of 1 or 2.8 MHz.

Prior work used to investigate bulk near-surface properties and surface roughness relied on characterizing the coherent and incoherent content encompassed in the total surface return [7]. They utilized radar observations collected at near constant altitude (h). However, Europa Clipper and JUICE will perform flybys throughout their nominal tours, where altitude rapidly changes across the observation window. Thus, understanding how changes in altitude can affect the balance between observed coherent and incoherent backscattered energy is needed to confidently apply reflectometry for these missions.

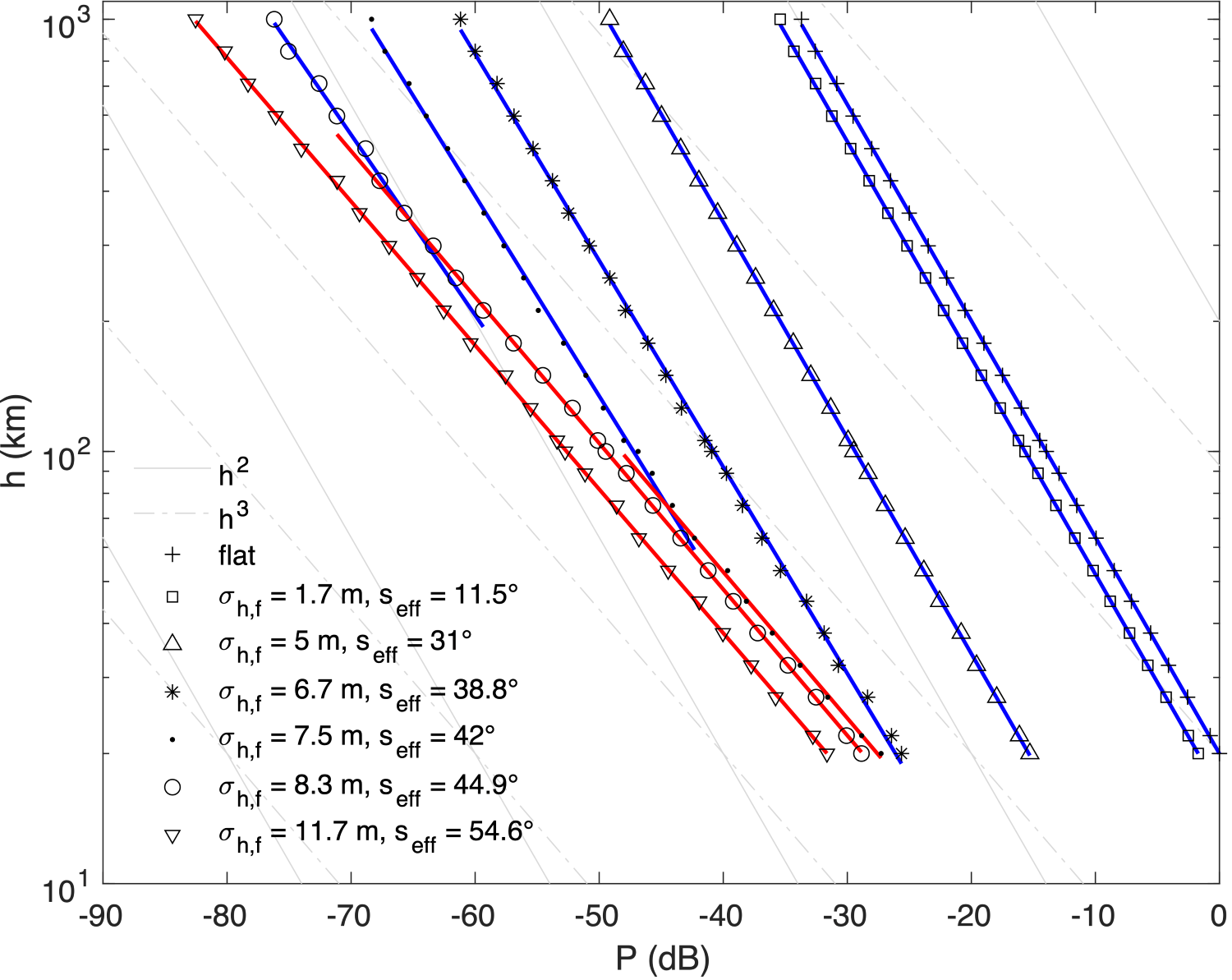

Here, we simulate the radar surface echo from synthetic terrains, using a version of the multilayer Stratton-Chu coherent simulator with rough facets [8]. We assess the coherent content of the total surface power to changes in altitude and surface roughness, by comparing the power derived from simulated surface echoes at 9 MHz center frequency (Fig.1). Coherent and incoherent power falls off at different rates (h2 versus h3, respectively) with increasing altitude [9]. The coherent content of the total return at a particular altitude over the target of interest could be utilized to invert for near-surface properties. Therefore, increasing platform altitude could be leveraged as a natural filter to establish stable coherent returns.

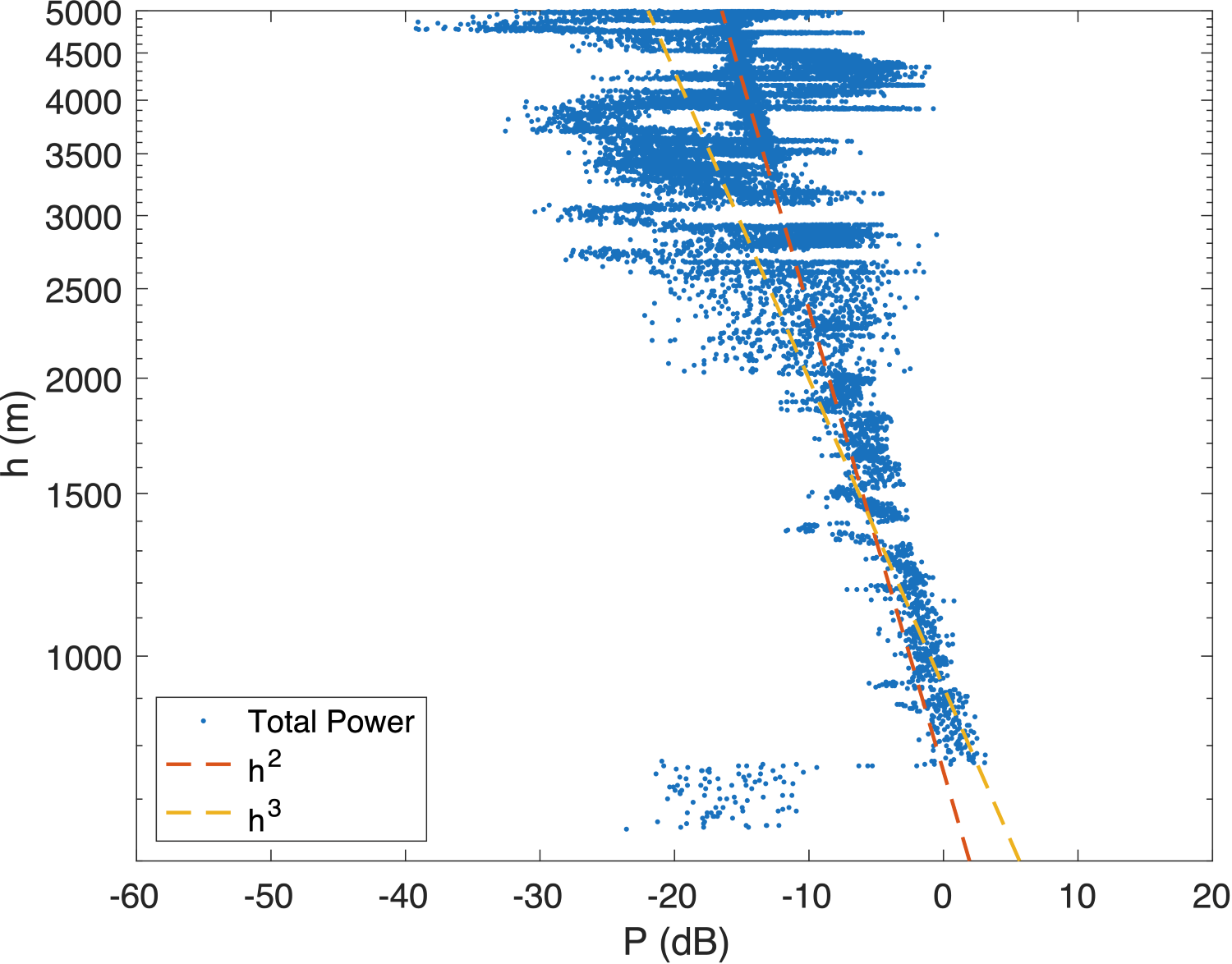

We further validate this approach for reflectometry with ice-penetrating radar data collected over Beardmore Glacier, Antarctica. These data were collected with the Multifrequency Airborne Radar-sounder for Full-phase Assessment (MARFA) instrument, a 60 MHz airborne radar sounder operated by the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics [10]. This particular groundtrack was flown to incorporate altitude variations that scale with the center frequency of the HF channel of RIME and REASON. We find that power fall-off is neither entirely proportional to h2 nor h3 (Fig. 2). This suggests that the surface return consists of both coherent and incoherent energy, perhaps characteristic of cracks and crevasses as well as changes in firn porosity (i.e., icy regolith) across the glacier’s surface. In the case of RIME and REASON, this work implies that different terrain types (e.g., chaos terrains versus ridged plains on Europa) may be better observed at certain altitudes from the perspective of reflectometry. In addition, our results can provide insight into favorable targets and altitudes suitable for cross calibrating RIME and REASON at their shared center frequency and bandwidth to enable comparative radar studies across the Jovian icy moons. This science objective has been recommended in the latest JUICE-Clipper Steering Committee (JCSC) orbital report.

Fig 1. Simulated surface power (P) for synthetic terrains with stationary surface roughness, for altitudes ranging from 20 to 1000 km. Simulations were conducted with correlation length lc = 0.25λ.

Fig 2. Observed surface power (P) over Beardmore Glacier for altitudes ranging from 600 to 5000 m.

References

[1] Daubar et al. (2024) SSR, 220(1), 18. [2] Moore et al. (1999) Icarus, 140(2), 294-312. [3] Grima et al. (2012) Icarus, 220(1), 84-99. [4] Chan et al. (2023) The Cryosphere, 17, 1839–1852. [5] Blankenship et al. (2024) SSR, 220(5), 51. [6] Bruzzone et al. (2015) IEEE IGARSS, 1257-1260. [7] Grima et al. (2014) P&SS, 103, 191-204. [8] Gerekos et al. (2023) Radio Science, 58(6), 1-30. [9] Haynes et al. (2018) IEEE TGRS, 56(11), 6571-6585 [10] Young et al. (2016) Phil Trans of the Royal Society A: MPES, 374(2059), 20140297

How to cite: Chan, K., Grima, C., Gerekos, C., Desage, L., Young, D., Blankenship, D., and Patterson, W.: Altitude-dependent radar reflectometry to characterize the near-surface of Jovian icy moons: perspectives from an Antarctic terrestrial analog, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-865, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-865, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

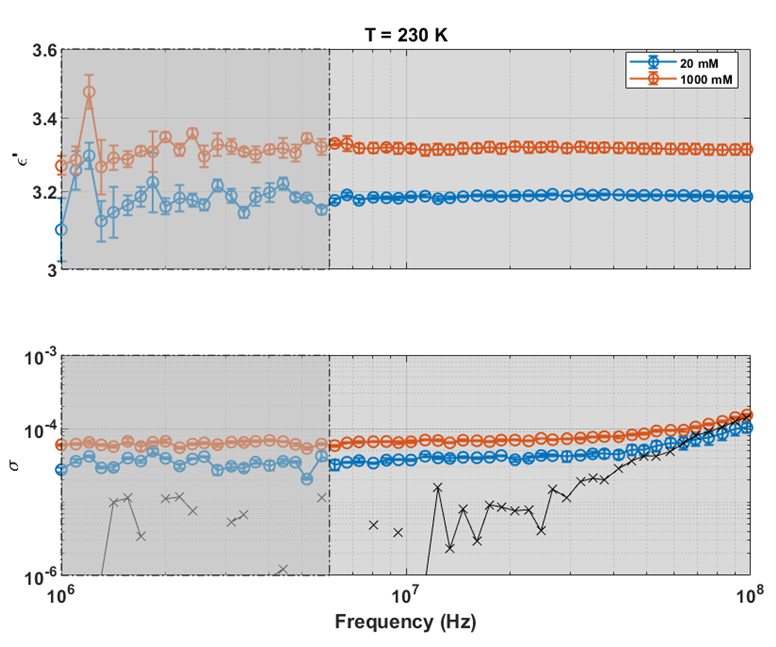

Introduction Jovian icy moons, Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto, due to the presence of liquid water oceans beneath their icy crusts [1] are extremely interesting for astrobiological and geological studies. Since radio echo sounding technique (RES) has proven to be very effective in the search for liquid water evidence on Earth [2] and in the Solar System [3] it will be employed in the analysis of these icy satellites. Two radars, RIME [4] and REASON [5], onboard JUICE and Europa Clipper missions respectively, will probe their interior to search for possible habitable environments. Radar data are affected by electromagnetic properties of the materials that the radio signals penetrate, then the knowledge of these properties is fundamental to analyse data and prevent incorrect interpretations. The goal of this work is to use laboratory measurements of dielectric properties of icy crust analogues and to simulate the signals propagation to reproduce future radars data.