- 1Physics Institute, University of Bern, Switzerland (haruna.toyoshima@unibe.ch)

- 2Graduate school of Science, Kobe University, Japan

- 3Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Japan

Titan's surface is covered by a thick atmosphere, much of which remains unexplored. Radar observations by the Cassini mission (2004‒2017) captured high-resolution images of approximately 69% of the surface, revealing a landscape rich in methane seas and rivers, with both dry and wet regions. Notably, Titan's surface has very few impact craters, which is the main geological feature used to estimate past impact fluxes or surface ages through crater

size-frequency distributions (CSFDs). This scarcity of craters is not only due to atmospheric shielding, which prevents many meteorites from reaching the surface, but also because Titan's surface, particularly the wet regions saturated with methane, is subject to intense erosion and

sediment deposition [1].

Wood et al. (2010) identified 49 possible impact craters across 22% of Titan's surface and reported that these features had been modified by various processes, including fluvial erosion, mass wasting, burial by dunes, and submergence in seas [2]. As a result, estimating surface

age from CSFDs is particularly challenging on Titan. Alternatively, Neish et al. (2013) and Rossignoli et al. (2022) proposed estimating surface age using impactor size-frequency distributions (SFDs) [3, 4]. Rossignoli et al. (2022) modelled the impactor SFD reaching Titan's surface under the assumption that most impactors originated from the Centaur population. Their analysis incorporated atmospheric shielding and used crater scaling laws

for icy targets to relate impactor size to crater size.

However, Titan's surface often retains liquid methane, which can alter key physical properties relevant to crater formation, such as friction, cohesion, and porosity. In this study, we conducted high-velocity impact experiments on wet sand targets with varying water contents to establish a crater size scaling relationship for wet surfaces, taking into account the effects of liquid content. Although Titan's wet surface would be composed of ice particles containing liquid methane, wet sand could serve as a suitable analogue, exhibiting similar physical characteristics during a cratering process. Using the impactor SFD proposed by Rossignoli et al. (2022), we estimated the original CSFD on Titan prior to erosion, enabling comparison with the currently observed CSFD to assess erosional effects on crater retention. Additionally, we performed numerical simulations to reconstruct the original morphology of Titan's craters before erosion and compared these with crater profiles observed by Cassini's Synthetic Aperture Radar to evaluate the degree of erosional modification.

Impact experiments: We conducted high-velocity impact experiments on wet sand targets using two-stage horizontal and vertical light gas guns at Kobe University and ISAS (JAXA). We used spherical aluminum or polycarbonate projectiles with the diameters of 2.0 mm or 4.7 mm. The impact velocities were 2-6 km/s. For the horizontal gas gun, the targets were tilted at 30°from the horizontal plane to simulate oblique impacts, while for the vertical gas gun,

targets were placed horizontally to simulate vertical impacts. The targets consisted of a homogeneous mixture of quartz sand (average grain size: 500 μm)

and water in varying proportions. For impacts with 2.0 mm projectiles, the mixture was placed in acrylic containers measuring 150 mm × 150 mm × 50 mm; for 4.7 mm projectiles, containers measured 200 mm × 200 mm × 100 mm. The water content was varied from 0 to

13 wt.%, which reduced the target porosity from 47% to 21% as water filled the pore spaces.

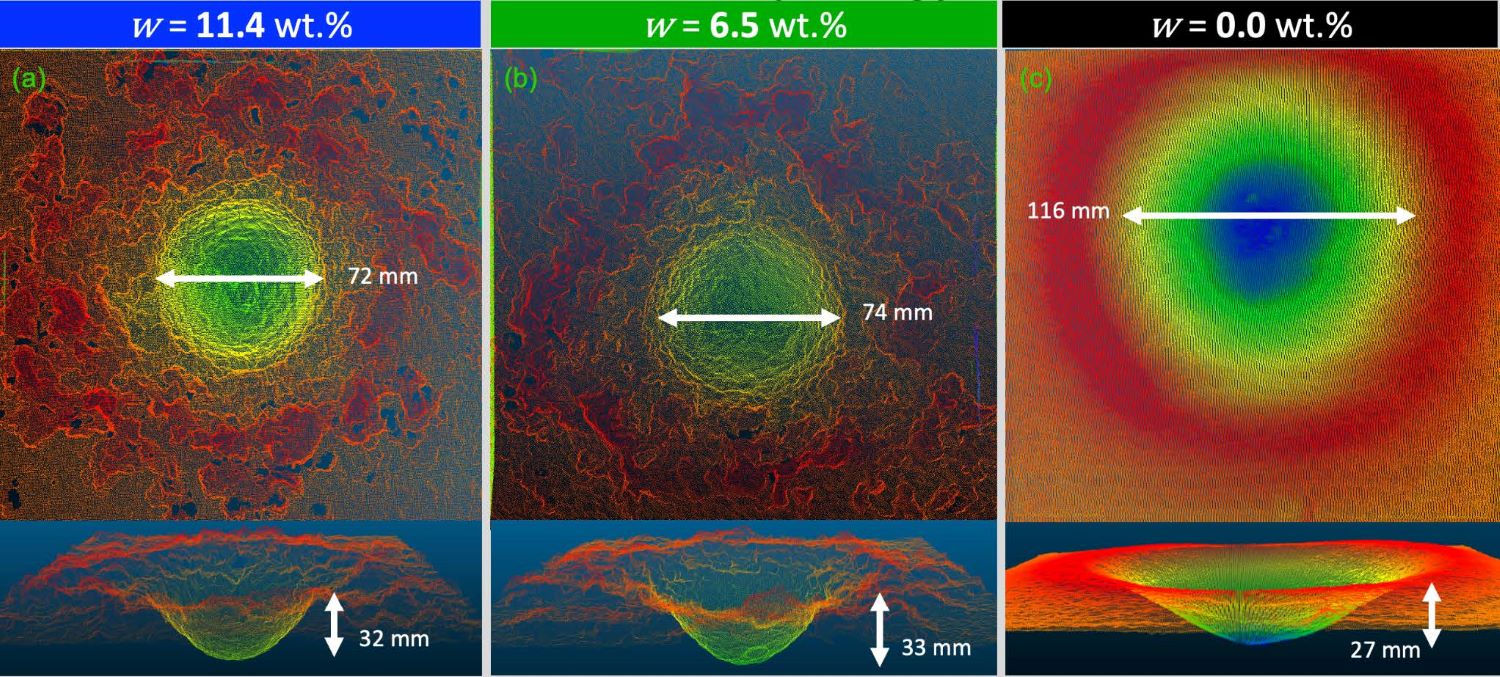

All experiments were recorded using two high-speed cameras. After impact, the final crater profiles were measured using either a 3D scanner or a 2D laser displacement indicator (Fig.1). These profiles were then used to calibrate our numerical model.

Fig. 1: 3D crater profiles from experiments on wet sand with varying water contents (wt%) showing distinct crater morphologies.

Numerical models: We use Bern's parallel Smooth Particle Hydrodynamics (Bern SPH) impact code [5, 6] to reproduce and extend our experimental results. This SPH code has been previously validated against laboratory experiments, including quartz sand targets [e.g., 7, 8].

Results and Discussion: The craters formed in our experiments were influenced by changes in target water content, affecting not only cohesion but also the coefficient of friction. We established a crater size scaling relationship for wet sand by accounting for these water content effects, using the π-scaling framework developed by Housen and Holsapple (1993):

Where with crater radius R, target density ρ , projectile mass m, gravitational acceleration g, projectile radius a, impact velocity U, impact angle θ, and water content wc. For a detailed derivation of our scaling relationship,

see Toyoshima et al. (2024) [9].

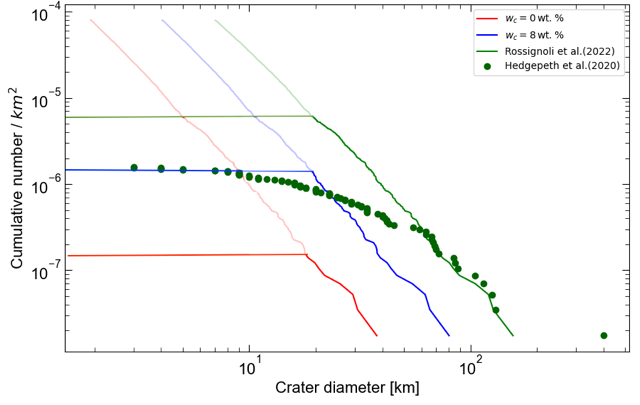

We used the impactor SFD from Rossignoli et al. (2022), which follows a broken power-law model for Centaur objects, to calculate the expected original CSFD on Titan (Eq. 2; C0=3.5 ×105×100(s2-1), s1=4.7, s2=3.5). They also included the atmospheric effects such as deceleration and ablation of impactors, and concluded that CSFD would become constant at crater size < 25 km. Figure 2 shows that the CSFDs for our scaling relationship is less than that for Rossignoli et al. (2022), and also it differs by approximately an order of magnitude between wet and dry targets. This suggests that the CSFD would indicate a younger surface age than previously estimated if we use our scaling relationship, and the estimated age would vary with surface liquid content. Further analysis is needed to refine the application of the impactor SFD. In our presentation, we will discuss the estimated surface age of Titan, crater retention ages, and the erosional effects on crater morphology. Eq.(2)

Fig. 2: Crater size-frequency distributions (CSFDs) on Titan for an icy target (from Rossignoli et al. (2022)) and for targets with varying water content (wt%) (this study). These CSFDs were calculated using the impactor size-frequency distribution from Rossignoli et al. (2022). Green markers indicate the observed CSFD from Hedgepeth et al. (2020) [10].

Citation:

[1]Cornet et al. (2015). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 120(6), 1044‒1074.

[2] Wood, C.A., et al. (2010). Icarus, 206, 334‒344.

[3] Neish, C.D., et al. (2013). Icarus, 223(1), 82‒90.

[4] Rossignoli, N.L., et al. (2022). A&A, 660, A127.

[5] Jutzi, M., et al. (2008). Icarus, 198, 242‒255.

[6] Jutzi, M. (2015). PSS, 107, 3‒9.

[7] Ormö, J., et al. (2022). EPSL, 594, 117713.

[8] Raducan, S.D., et al. (2021). LPSC, #1908.

[9] Toyoshima, H., et al. (2024). JGR-Planets, submitted.

[10] Hedgepeth, J.E., et al. (2020). Icarus, 344, 113664.

How to cite: Toyoshima, H., Raducan, S., Arakawa, M., Hasegawa, S., and Jutzi, M.: Impact cratering on wet surface : Implications to the erosional degree on impact craters on Titan , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-285, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-285, 2025.