- Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Department of Geophysics, Prague, Czechia (kanovami@gmail.com)

Introduction

Owing to its proximity to the Sun, the large eccentricity of its orbit (e=0.2), and the action of tidal forces, Mercury is locked in a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance: it turns exactly three times around its rotation axis during two revolutions around the Sun. However, this might not have always been the case. As identified by several studies [1,2], the geographical distribution of large impact basins on Mercury’s surface indicates that the planet might have been locked in a different spin-orbit resonance in past, with the most likely rotation states being the 1:1 and the 2:1 resonances [2]. A past transition between spin states, which resulted in a change of the insolation and surface temperature patterns, is also indicated by the relaxation states of the basins and by the hemispheric nature of some tectonic features [3,4].

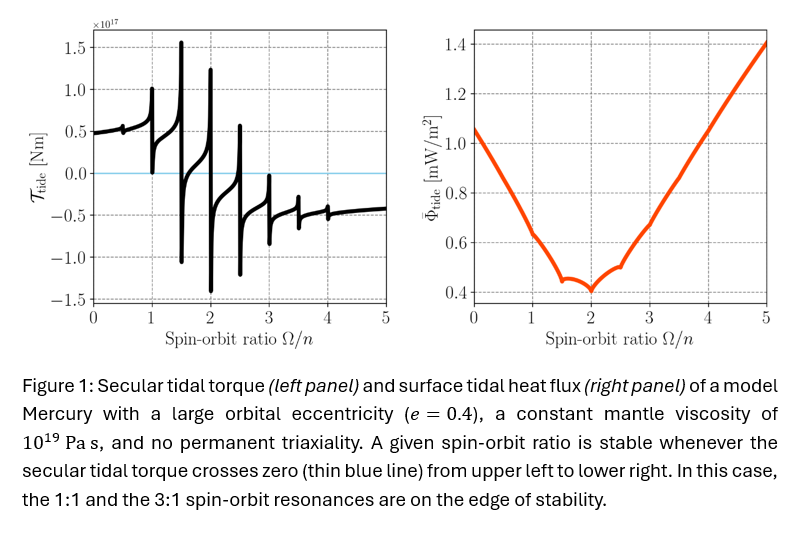

The stability of spin-orbit resonances depends on several factors (Figure 1), the most important ones being the orbital eccentricity, the planet’s rheological parameters, and its prolateness. Mercury’s orbit is subjected to relatively fast eccentricity variations between e=0 and e=0.3 with a period of ~106-107 years and potential chaotic high-eccentricity excursions beyond e=0.4 resulting from its proximity to an overlap of secular resonances with Venus and Jupiter [5,6]. While the present-day 3:2 spin-orbit resonance is, in general, stable for a range of eccentricities [7], its stability might be diminished at very small or large eccentricites, especially if Mercury’s mantle was more dissipative or if the planet was less prolate earlier in the history.

Model and Methods

This study combines the modelling of Mercury’s interior structure and the analysis of stable spin states under the varying action of solar tides. The interior structure is determined by Bayesian inversion, using the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method [8] and estimating the probability distributions over several interior structure parameters (e.g., the core size, the concentration of light elements in the core, and the temperature profile) consistent with empirically constrained observables (e.g., the mean density, the moment of inertia of the planet, the relative moment of inertia of the mantle, and the tidal Love numbers).

Selected interior profiles are then endowed with different viscosities and used in simulations of the orbital evolution of Mercury and the other solar system planets. I investigate the changes in Mercury’s rotation rate (including transitions between spin-orbit resonances) arising due to the variations in eccentricity and, potentially, due to the changes in the planet’s shape, which is subject to viscoelastic relaxation. At the same time, I evaluate the tidal heat rate and identify periods when it might have presented a non-negligible contribution to the planet’s thermal evolution. The orbital evolution is calculated with the symplectic integrator Rebound [9], coupled with a tidal model developed previously [10] and based on the Darwin-Kaula expansion of evolution equation as presented in [11]. The tidal model accepts as an input the radially-dependent elastic and rheological parameters of Mercury and outputs the tidal contribution to the evolution rates of all orbital elements as well as the closest stable spin-orbit resonance and the associated tidal heating.

Both in the interior structure inversion and in the tidal-orbital model, Mercury is described as a viscoelastic differentiated body. Its mantle is characterised by the Andrade rheological model, the inner core by the Maxwell model, and the outer core is an inviscid fluid. The tidal response is calculated using the normal mode theory [12].

Preliminary conclusions

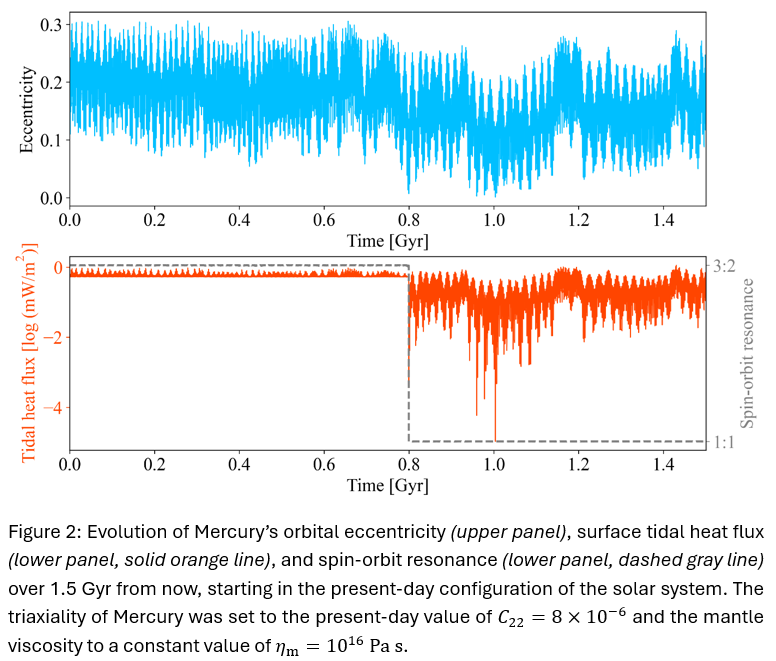

In concordance with previous studies of the planet’s interior structure [e.g., 13], the large tidal deformability, encoded in Mercury’s tidal Love number k2, points at a low-viscosity zone in the lower mantle. The zone has viscosities in the range 1013-1018 Pa s, which might potentially account for an increased tidal dissipation. According to the preliminary results, Mercury can transition from the 3:2 resonance to the 1:1 resonance in about 1 Gyr from now if it keeps its present-day shape and if it is indeed highly dissipative (Figure 2). A coupled study of the orbital and tidally-induced rotational evolution can provide constraints on the rheology and thus the thermal state of Mercury that are consistent with the stability of the 3:2 spin-orbit resonance or any other hypothetical spin state in past [1,2]. It also shows that the eccentricity variations, combined with decreased mantle viscosity, can lead to transitions between different spin states without the need for impact-induced resonant unlocking.

References

[1] Wieczorek et al. (2012), Nature Geoscience, 5(1):18-21, doi: 10.1038/ngeo1350.

[2] Knibbe & van Westrenen (2016), Icarus, 281:1-18, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.08.036.

[3] Szczech et al. (2024), Geophysical Research Letters 51(22), doi: 10.1029/2024GL110748.

[4] Szczech et al. (2025), submitted to AGU Advances.

[5] Lithwick & Wu (2011), The Astrophysical Journal, 739(31), doi: 10.1088/0004-637X/739/1/31.

[6] Laskar & Gastineau (2009), Nature, 459(7248):817-819, doi: 10.1038/nature08096.

[7] Noyelles et al. (2014), Icarus, 241:26-44, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2014.05.045.

[8] Foreman-Mackey et al. (2013), Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific 125(925), doi: 10.1086/670067.

[9] Rein& Liu (2012), Astronomy & Astrophysics 537(A128), doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/201118085.

[10] Walterová & Běhounková (2020), The Astrophysical Journal 900(1), doi: 10.3847/1538-4357/aba8a5.

[11] Boué & Efroimsky (2019), Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 131(7), doi: 10.1007/s10569-019-9908-2.

[12] Takeuchi & Saito (1972), Methods in Computational Physics, 11:217-295, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-460811-5.50010-6.

[13] Goossens et al. (2022), The Planetary Science Journal, 3(2): id.37, doi: 10.3847/PSJ/ac4bb8.

How to cite: Walterova, M.: Spin-orbit resonances and tidal heating of Mercury in light of its chaotic orbital evolution, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-299, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-299, 2025.