- 1SES,JHUAPL, Laurel, MD, USA

- 2NASM, Smithsonian Institute, Washinton D.C., USA

- 3CLASP, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Recently, data from the OSIRIS-REx mission revealed evidence of layering, where fine-grained material on Bennu could be located at depth, not far below the asteroid’s surface (Bierhaus et al., 2023). If present and distributed globally, this fine-grained material could be more cohesive than the coarser and typically unconsolidated surface material, and would provide a relative stronger substrate at depth. Several lines of evidence indicate that Bennu’s interior should possess such strength, including but not limited to its non-circular equatorial ridge (Barnouin et al., 2019), the presence of surface lineaments (Barnouin et al., 2019; Jawin et al., 2022), and the widespread evidence of surface mass movement (Barnouin et al., 2022; Jawin et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2023; Walsh et al., 2019). Understanding properties including cohesion, particle size distribution, and structure is key to interpreting an asteroid’s geologic history. One manifestation of our uncertainty in asteroid surface properties is a mismatch in the crater-derived surface ages of NEAs such as Bennu and Ryugu, which are orders of magnitude younger than the proposed age of the breakup of their parent bodies.

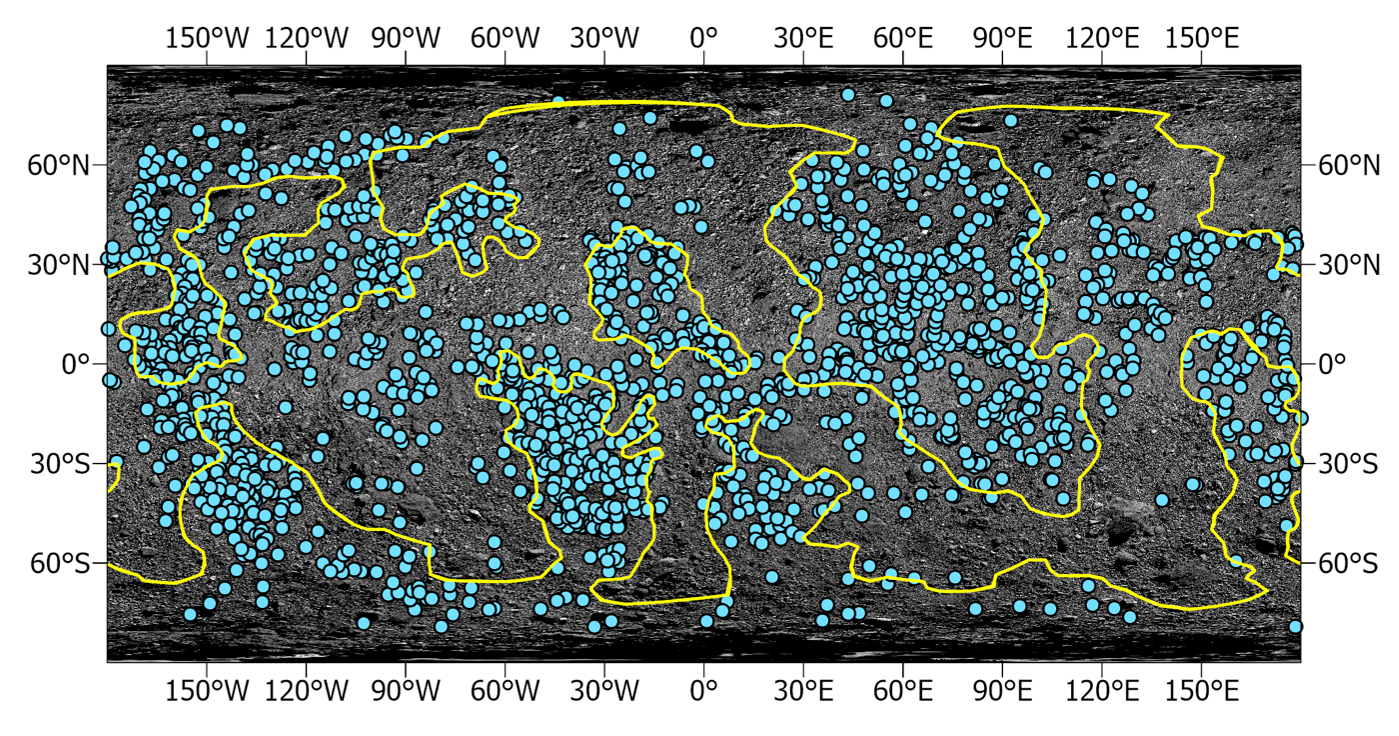

Figure 1. Global image mosaic showing smooth regions larger than ~1 m (circles) compared to global geologic units (yellow outline). Smooth regions are concentrated in the Smooth Unit (regions including the north and south poles), although smooth exposures are also present in the Rugged Unit (covering most of the equatorial zone).

Here, we begin to explore in detail the spatial distribution and physical attributes of the exposed subsurface, fine-grained layer. Our approach is to systematically identify smooth areas across the asteroid, where the more cohesive fines might exist, with the ultimate objective to test the hypothesis of the presence of this fine-grained subsurface layer, in part by establishing the stratigraphic height of any exposed fine-grained material.

Identifying smooth areas:

We visually identify smooth regions in a global image mosaic generated from the Detailed Survey phase of the mission with a pixel scale of ~5 cm (Bennett et al., 2021) (Fig. 1). This initial mapping identified relatively smooth-textured areas regardless of objective roughness or geologic setting (i.e., not restricted to impact craters). Additional analyses will survey the polar regions, define spatial extents of smooth exposures, merge overlapping regions, remove any regions smaller than our minimum diameter of 5 m, and will identify regions for subsequent SFD analyses.

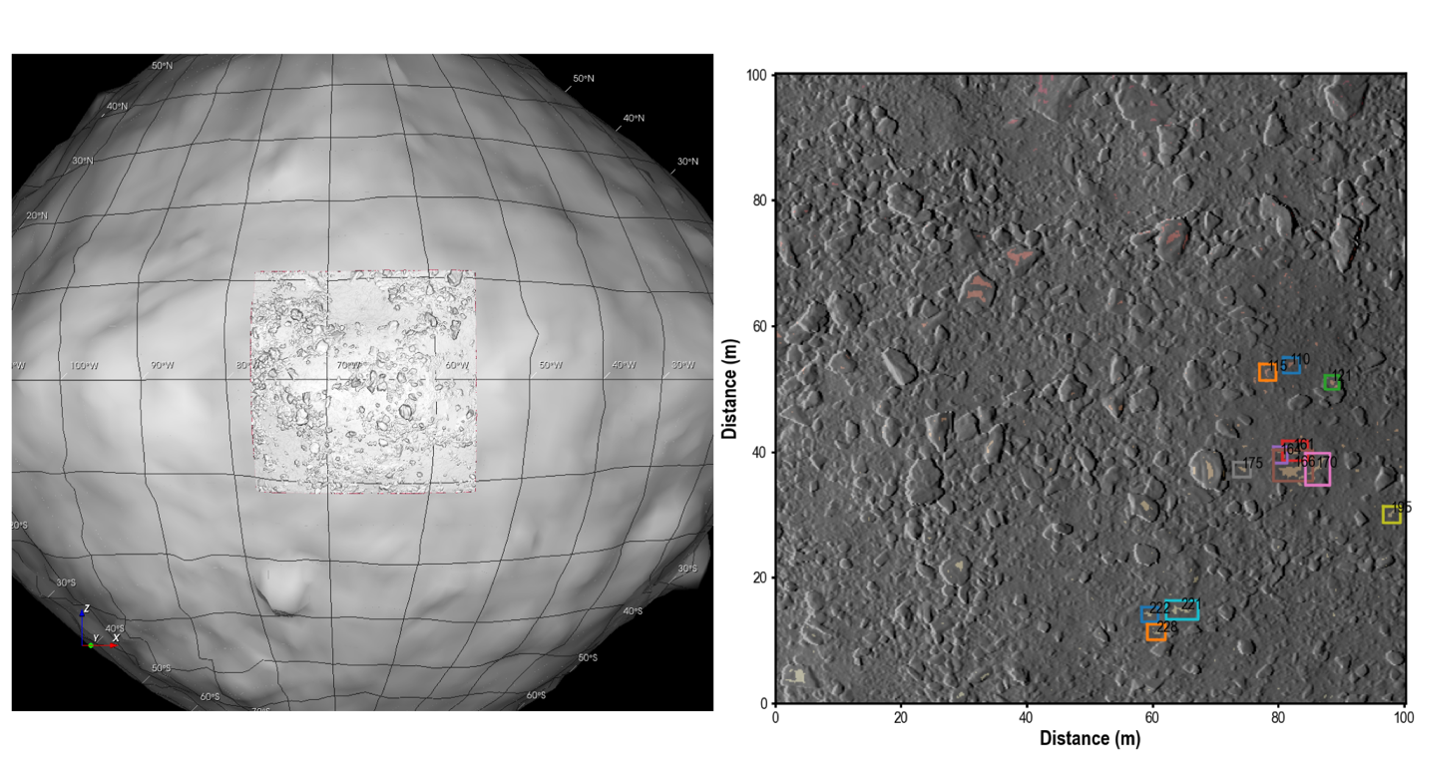

We also identify and map smooth regions on a global set of 20 cm digital terrain models (DTM) that were generated using OLA data collected during the prime mission. As available in the Small Body Mapping Tool, these 20 cm DTMs include the variation of surface tilts across the surface of Bennu, within a 1-m diameter region, centered on each one of the DTM’s facet. The tilt variation is determined by taking the root mean square of variation of each facets tilt relative to the mean tilt of 1 m region. Surfaces that have a greater tilt variation are typically rougher than regions that do not. To find the smoothest areas, we filter this tilt variation < 4 deg. We also filter out boulder tops, many of which are very smooth (Fig. 2). The remaining regions are tracked by location, elevation, radius, and so on.

Fig. 2 Twenty-cm DTM located on Bennu (left), with smooth regions identified (right) as colored patches. Boxed regions were ultimately considered in this analysis. Other patches are usually boulder tops, which are often smooth.

Numerical assessments

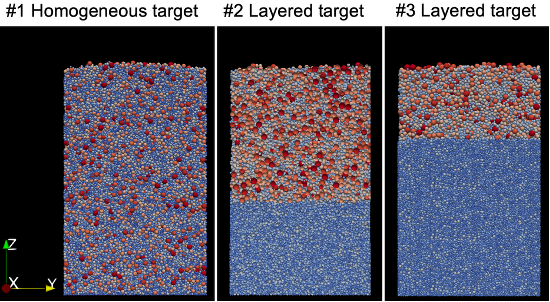

To complement our systematic mapping efforts, we have also undertaken a suite of numerical investigations that make use of the Soft-Sphere Discrete Element Model code PKDGRAV. We hypothesize that a near-surface layer of fine-grained material, owing to its stronger cohesion, could facilitate mobilization of the overlying coarse regolith, thereby enhancing surface mass movement compared to an unlayered target. If this hypothesis is correct, then the geotechnical properties of the granular material should depend on: (1) particle SFD, (2) particle size range, and (3) confining pressure. To systematically study how these factors interact and influence the mechanical behavior of Bennu’s surface and near-surface regolith, we perform triaxial compression tests using PKDGRAV. We further conduct landslide simulations using granular beds with various surface and subsurface structures (Fig. 3) to assess their surface mobility. These efforts consider Bennu gravitational conditions.

Fig. 3 Examples of subsurface structures used in the numerical simulations for testing surface mobility. Particles are color-coded by their radii.

Current status of findings:

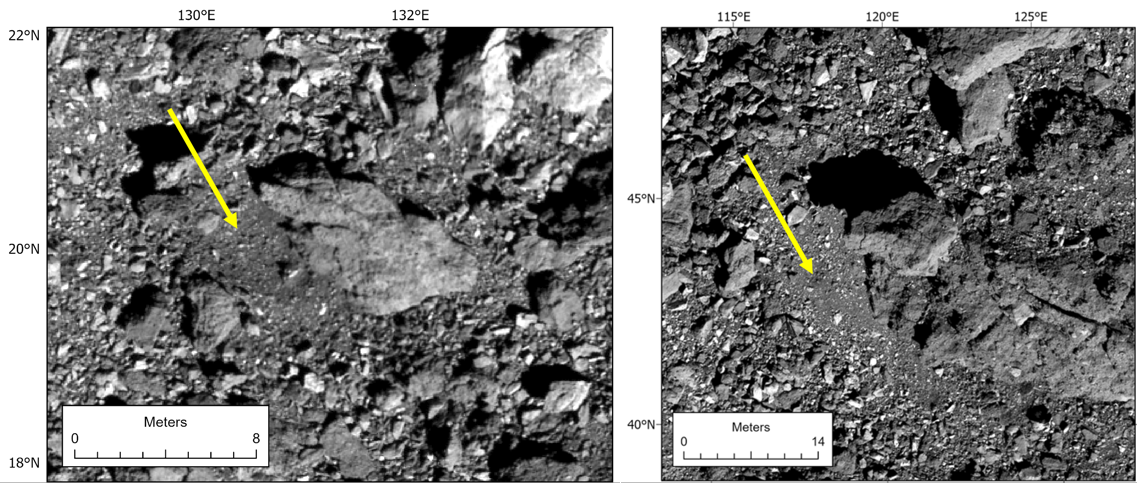

Our initial spatial trends suggest that smooth exposures are more prevalent in the Smooth Geologic unit (compared to the Rugged unit), although smooth regions are also found in the Rugged unit that may be associated with the movement of large boulders via impacts and/or mass movement (Fig. 1). We also find that smooth areas are often, but not always, associated with small fresh (red) craters. Many of the smoothest regions also exist between boulders, including the largest boulders (>20-30 m diameter) which have previously been associated with recent mass movement activity (Daly et al., 2020; Jawin et al., 2020). Some of the most interesting smooth regions are found down-slope of a larger boulder, where coarse surface material appears to have slid away, exposing the fines (Fig. 4?). Our ongoing numerical investigation will provide a better understanding for what near-surface conditions were needed to achieve these observations.

Figure 4. Examples of smooth regions downslope of large boulders on Bennu.

References:

Barnouin, O.S., et al., 2019. Nature Geoscience 12, 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0330-x

Barnouin, O.S., et al., 2022. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 127, e2021JE006927. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JE006927

Bennett, C.A., et al., 2021. Icarus 357, 113690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2020.113690.

Bierhaus, E.B., et al., 2023. Icarus 115736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115736

Jawin, E.R., et al., 2022. Icarus 381, 114992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2022.114992

Jawin, E.R., et al., 2020. J Geophys Res-Planet 125. https://doi.org/10.1029/2020JE006475

Tang, Y., et al., 2023. Icarus 115463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115463

Walsh, K.J., et al., 2019. Nature Geoscience 12, 242–246. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0326-6

How to cite: Barnouin, O., Jawin, E., and Yun, Z.: Characterizing a near-surface, fine-grained layer on Bennu. , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-346, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-346, 2025.