- Tel Aviv University, Faculty of Exact Sciences, Porter School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Israel (adamparhi@mail.tau.ac.il)

The incentive for studying the continuous evolutionary path of comets stems from recent developments in observational astronomy, which allow us to monitor comets at unprecedented heliocentric distances. New data from highly sensitive instruments—most notably the James Webb Space Telescope—reveal that many comets become active far from the Sun, at distances where temperatures are too low to allow for water ice sublimation. Recent examples include C/2014 UN271 Bernardinelli-Bernstein (Farnham et al. 2021), an Oort Cloud (OC) comet, which was already active at 20 au and C/2017 K2 PanSTARRS, another OC comet, found active at 16 au pre-perihelion (Yang et al. 2021). More recently, long-period comet C/2024 E1 Wierzchos was observed to exhibit activity driven by CO2 at a heliocentric distance of 7 au (Snodgrass et al. 2025). These observations suggest the presence of other mechanisms and volatile species driving the detected activity.

There have been attempts to understand the long-term thermal processing of comet nuclei using theoretical estimates and numerical models. The simplest approach is to consider the saturated vapor pressure that controls the sublimation rate as a function of temperature for the most common volatiles detected in comets. Since the temperature is related to the heliocentric distance, this gives an idea of the time needed to lose a volatile species at a given distance from the Sun (Lisse et al. 2021). However, this remains an approximate estimate, since it presumes that all volatile constituents of the comet body are uniformly exposed to solar radiation, without considering the internal composition and structure. Recent studies by Gkotsinas et al. (2024) have used simplified thermal evolution models that track temperature changes in conjunction with the dynamical evolution from the Kuiper Belt and the OC inward (Gkotsinas et al. 2022; Guilbert-Lepoutre et al. 2023), but they explicitly acknowledge that temperature profiles alone are insufficient—and potentially misleading—indicators of internal thermal evolution.

We present a fully integrated model of cometary evolution that couples thermal and compositional processes with dynamical processes continuously, from formation to present-day activity. The combined code takes into account changes in orbital parameters that define the heliocentric distance as function of time that is fed into the thermal/compositional evolution code. The latter includes a set of volatile species, gas flow through the porous interior, crystallization, sublimation and refreezing of volatiles in the pores (Prialnik et al. 2004, Parhi and Prialnik 2023).

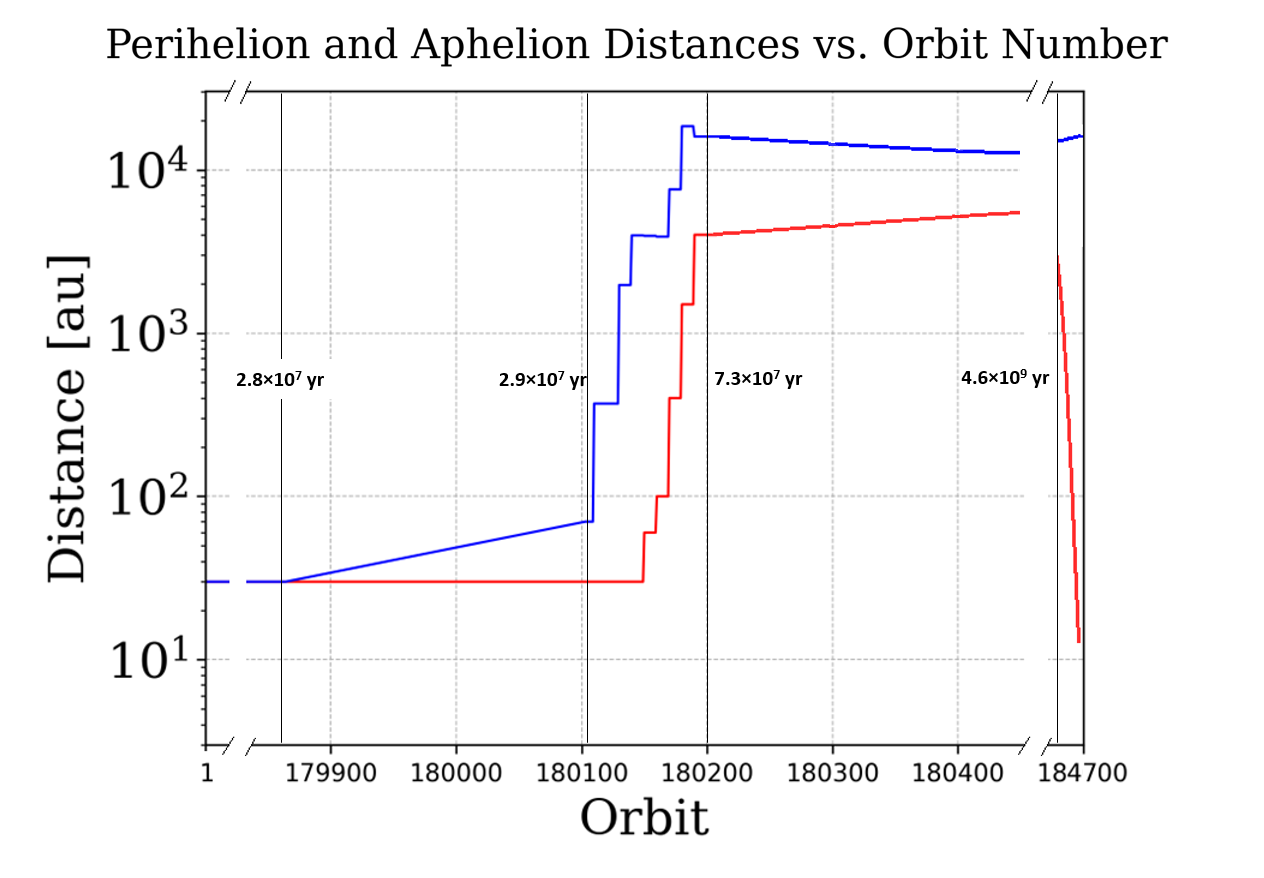

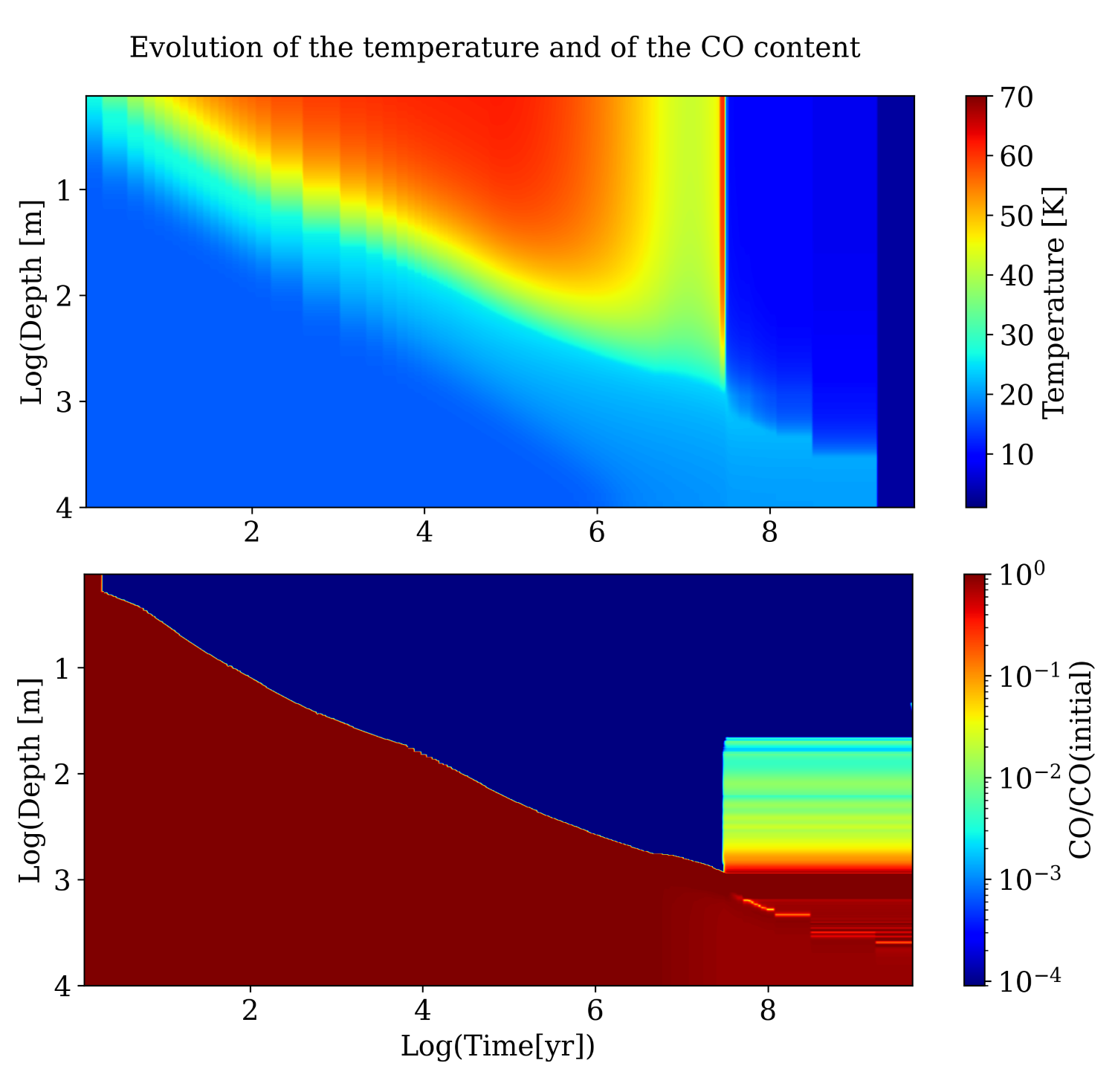

We follow the evolution of a 10 km radius model for 4.5 Gyr, through different epochs, starting in the vicinity of Neptune, moving to the OC and then back inwards to the planetary region. The initial composition includes a mixture of CO, CO₂ ices, amorphous water ice with trapped CO and CO₂ , and dust. The evolution of the eccentric orbits is shown in Fig.1, and the evolution of the temperature is shown in Fig.2. We find that the CO ice is gradually lost during the first 5.5 Myr of evolution, while the CO₂ and the amorphous ice are entirely preserved. Upon return from the OC the activity is driven by CO₂ sublimation, starting around 15 au and slowly declining as the CO₂ sublimation front recedes from the surface. It is rekindled at ~7 au, when the amorphous ice starts crystallizing and releasing the occluded gases.

These results are consistent with observations of LP comets (Meech et al. 2017), although they are not yet meant to simulate the behavior of any particular comet. Future studies will consider the effect of parameters and specific orbits of returning LP comets.

References

Farnham, T. L., Kelley, M. S., et al. (2021). The Planetary Science Journal, 2, 236.

Gkotsinas, A., Guilbert-Lepoutre, A., Raymond, S. N., & Nesvorny, D. (2022). The Astrophysical Journal, 928, 43.

Gkotsinas, A., Nesvorny, D., Guilbert-Lepoutre, A., Raymond, S. N., & Kaib, N. (2024). The Planetary Science Journal, 5, 243.

Guilbert-Lepoutre, A., Gkotsinas, A., Raymond, S. N., & Nesvorny, D. (2023). The Astrophysical Journal, 942, 92.

Lisse, C., Young, L., et al. (2021). Icarus, 356, 114072.

Meech, K. J., Kleyna, J. T., Hainaut, O. R., et al. (2017). The Astrophysical Journal, 849, L8

Parhi, A., & Prialnik, D. (2023). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 522, 2081.

Prialnik, D., Benkhoff, J., & Podolak, M. (2004). In Comets II, eds. Festou, Keller, & Weaver (p. 359).

Snodgrass, C., et al. (2025). arXiv preprint, arXiv:2503.14071.

Yang, B., Jewitt, D., et al. (2021). The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 914, L17.

Fig.1. Evolution of orbital parameters expressed by aphelion and perihelion distances.

Fig.2. Evolution of the surface temperature, the maximal temperature and the central temperature of the comet model. The surface temperature oscillates between aphelion and perihelion; for the most part, the maximal temperature occurs at the surface, hence the overlap.

Figure 1

Figure 2

How to cite: Parhi, A. and Prialnik, D.: Combined Long-term Orbital and Thermal Evolution Simulations of Oort Cloud Comets, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-388, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-388, 2025.