- 1Retired from University of Oulu, Space Physics and Astronomy Research Unit, Oulu, Finland

- 2Wellesley College, Department of Astronomy, Wellesley MA 02481, USA

- 3Astronomy Department, Cornell University, Ithaca NY 14853, USA

- 4Department of Physics, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID 83844, USA

Self-gravity wakes form in planetary rings via gravitational accumulation of ring particles, which is counteracted by differential rotation that tries to tear apart any forming condensations. This competition leads to a statistical steady state, with the continuous formation and destruction of local trailing density enhancements on timescales on the order of the ring orbital period. In unperturbed regions characterized by Keplerian shear, the average pitch angle of wakes with respect to the tangential direction is 15-25 degrees, depending on the strength of self-gravity with respect to the tidal force. The existence of such structures in Saturn’s A and B rings leads to azimuthal variations in ring optical depth and brightness, as they depend on the geometry of observation with respect to the local tangential direction (see Salo & Mondino-Llermanos, 2025).

In perturbed ring regions, the local shear rate may deviate significantly from its Keplerian value. This is the case, for example, in regions with satellite density waves, near non-circular ring edges, or inside eccentric ringlets exhibiting width variations. As a consequence, the average spacing and orientation of self-gravity wakes can be expected to change compared to those in unperturbed regions.

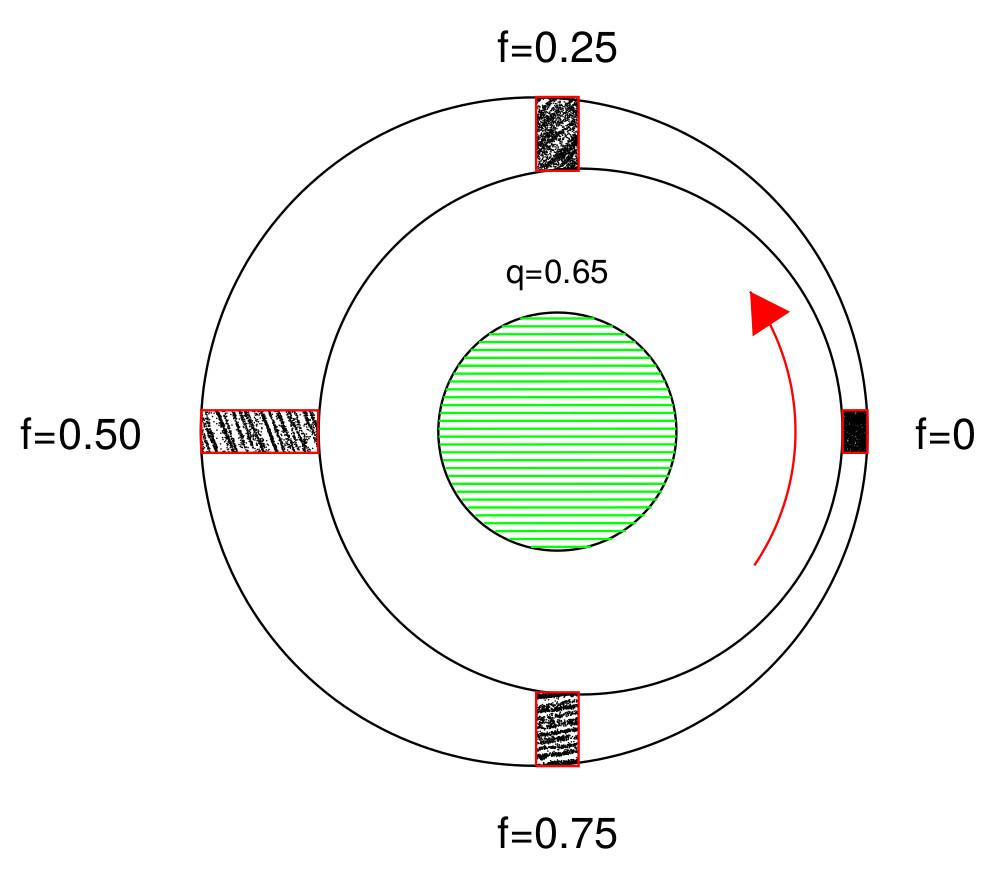

An efficient local method to simulate perturbed rings was devised by Mosqueira (1996). It is based on the fact that, from the viewpoint of an individual ring particle, such perturbations appear as periodic compression and decompression of the density in the vicinity of the particle (Fig. 1). This can be mimicked in a local simulation by: 1) assigning the initial particle velocities to follow the perturbed mean flow; 2) making the radial size of the simulated region follow the local density changes; and 3) using periodic boundary conditions that account for the perturbation-modified shear rate.

Fig. 1 Schematic illustration of the local simulation of an eccentric ring. Due to ring eccentricity gradient (de/da), the ring width varies as W=W90 (1-q cos(2πf)), where q = a de/da is the perturbation parameter, f is the orbital phase counted from the maximum compression, and W90 the ring width at quadrature (phase f=0.25). Due to width variations, the pitch angle of self-gravity wakes changes with the orbital phase: after the maximum compression, the wake structure emerges with a large pitch angle and winds tighter with the orbital phase (see Figs 2 and 3).

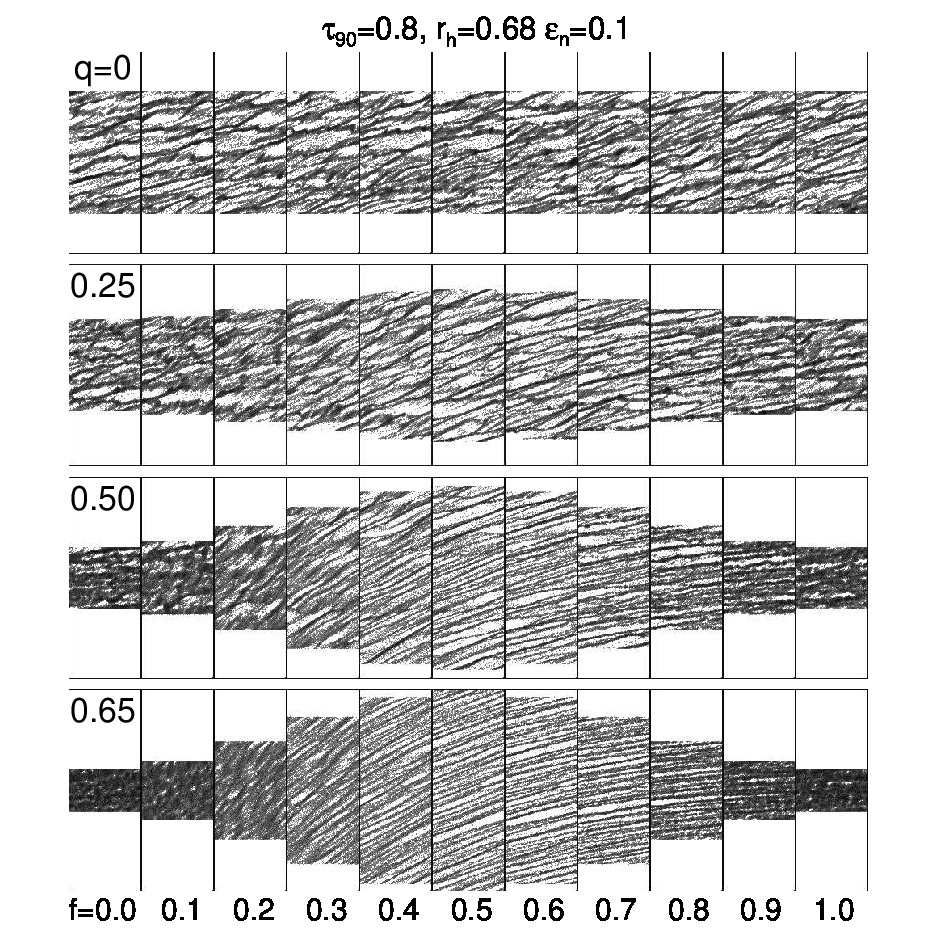

In the current study, we extend the Mosqueira (1996) method to take into account ring self-gravity, calculated self-consistently as described in Salo et al. (2018). The effect of different parameters on the self-gravity wake structure is systematically explored, including the strength of the perturbation (Figs. 2 and 3), as well as the properties of the underlying ring (strength of self-gravity, optical depth, particle size distribution, and elasticity of impacts). Besides dynamical modeling we also analyze how the photometric signatures of self-gravity wakes are modified in perturbed regions.

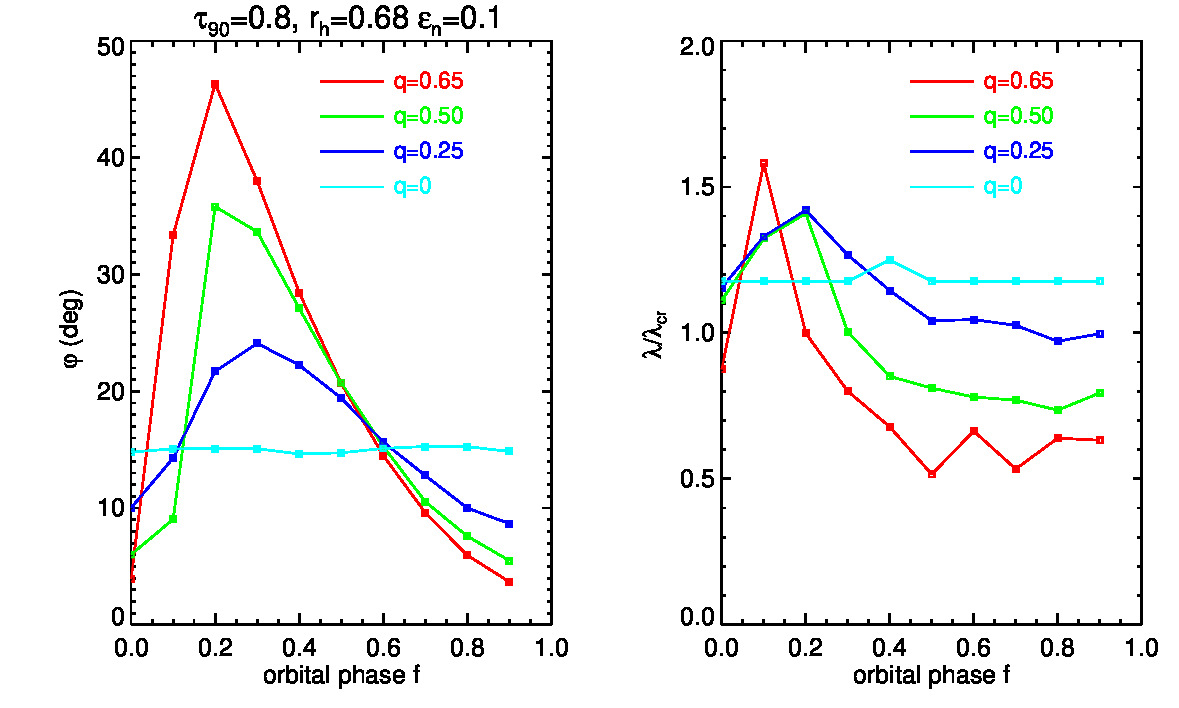

Preliminary application to the Uranian ε ring indicates very good agreement between the simulated self-gravity wakes and the local micro-structure deduced from the analysis of the Voyager 2 RSS scattered signal (French et al. in prep.). For the orbital phase of RSS egress observations (f=0.67), both observations and simulations (using q=0.65) give similar 10 degree pitch angle (Fig. 3). Modeling the wake spacing deduced from the RSS signal suggests that the ring particles have an internal density less than or approximately half that of solid ice.

References:

- Mosqueira (1996) "Local Simulations of Perturbed Dense Planetary Rings", Icarus 122, 128

- Salo & Mondino-Llermanos (2025) "Photometric modelling of self-gravity wakes and overstable oscillations in Saturn's rings ", A&A, 695, id.A37

- Salo & Ohtsuki & Lewis (2018) "Computer Simulations of Planetary Rings", in the book Planetary Ring Systems. Properties, Structure, and Evolution, Eds. M.S. Tiscareno and C.D. Murray.

Fig. 2 Influence of perturbation on self-gravity wakes when q increases from zero to 0.65. In each case, the evolution over one full orbit is displayed, for orbital phases f separated by 0.1 orbital periods (corresponding to different ring azimuths). In the snapshots the radial coordinate increases vertically and the prograde tangential direction is to the left. After the first few periods, the system attains a statistical steady state where a basically similar evolution repeats after each orbital cycle. The strength of gravity (rh=0.68) corresponds to that estimated for the mid-A ring in Salo & Mondino-Llermanos (2025). The size of the simulation system at f=0.25 corresponds to 10 by 12 Toomre critical wavelengths in the radial and tangential directions. The number of particles is N=48000.

Fig. 3 Pitch angle and wake spacing in the simulations of Fig. 2. The measurements were based on the 2D power-spectrum of the density field, averaged over snapshots corresponding to similar phases over 40 orbital cycles. Note how the pitch angle is reduced as the orbital phase increases from 0.25 to 1 (at f=0-0.25 the pitch angle is not well defined). For f ≥ 0.6, the pitch angle is significantly reduced and for f ≥ 0.2-0.4 the wake spacing becomes smaller compared to its non-perturbed value.

How to cite: Salo, H., French, R. G., Nicholson, P. D., and Hedman, M. M.: Simulations of self-gravity wakes in perturbed ring regions, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-391, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-391, 2025.