- 1Chengdu University of Technology, College of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Research Center for Planetary Science, China (taikairui@stu.cdut.edu.cn)

- 3Institute of Atomic and Molecular Physics, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, PR China

- 4State Key Laboratory of Space Weather, National Space Science Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 101499, PR China

- 5Center for High Pressure Science and Technology Advanced Research, Beijing 100193, PR China

- 6State Key Laboratory of Ore Deposit Geochemistry, Institute of Geochemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Guiyang 550081, PR China

- 7Key Laboratory of Earth and Planetary Physics, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, PR China

- 8Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, PR China

Abstract

Martian crust is enriched in iron, with olivine averaging an iron number of approximately 50. However, owing to the scarcity of terrestrial analogs with similar compositions, the shock behavior and preservation potential of Fe-rich olivine remain poorly understood. This study investigated the microstructural and spectral changes induced by shock effects in Fa50 Fe-rich olivine, providing new insights into its preservation, alteration mechanisms, and spectral evolution of Fe-rich olivine on the surfaces of Mars and Phobos.

Introduction

Iron is the second most abundant metal element in the solar system and plays a crucial role in planetary crustal evolution. Global remote sensing and in situ investigations indicate that Martian crust is enriched in iron, with olivine averaging an iron number (Fa#; Fe mola fraction of the Mg-Fe solid solution) of approximately 50. The silicates detected on Martian moons and some asteroids [1] potentially originated from Martian impact ejecta [2,3], suggesting that the primordial materials of Phobos and Deimos may contain iron-rich olivine given its abundance in the Martian crust [4]. However, due to the scarcity of terrestrial analogs with similar compositions, the shock behavior and preservation potential of Fe-rich olivine remain poorly understood, limiting our ability to assess how impacts modify its mineralogy and spectral properties on Mars and Phobos.

Methods

Shock recovery experiments were conducted on synthetic Fa50 olivine using one- and two-stage light gas guns at shock pressures of 18 GPa, 31 GPa, 41 GPa, and 47 GPa, corresponding to impact velocities between 0.89 and 1.95 km/s. Post-shock samples were analyzed using Raman, visible-near-infrared (VNIR), and mid-infrared (MIR) spectroscopy to assess spectral modifications. Microstructural and compositional features were characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), focused ion beam (FIB) sectioning, and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Results

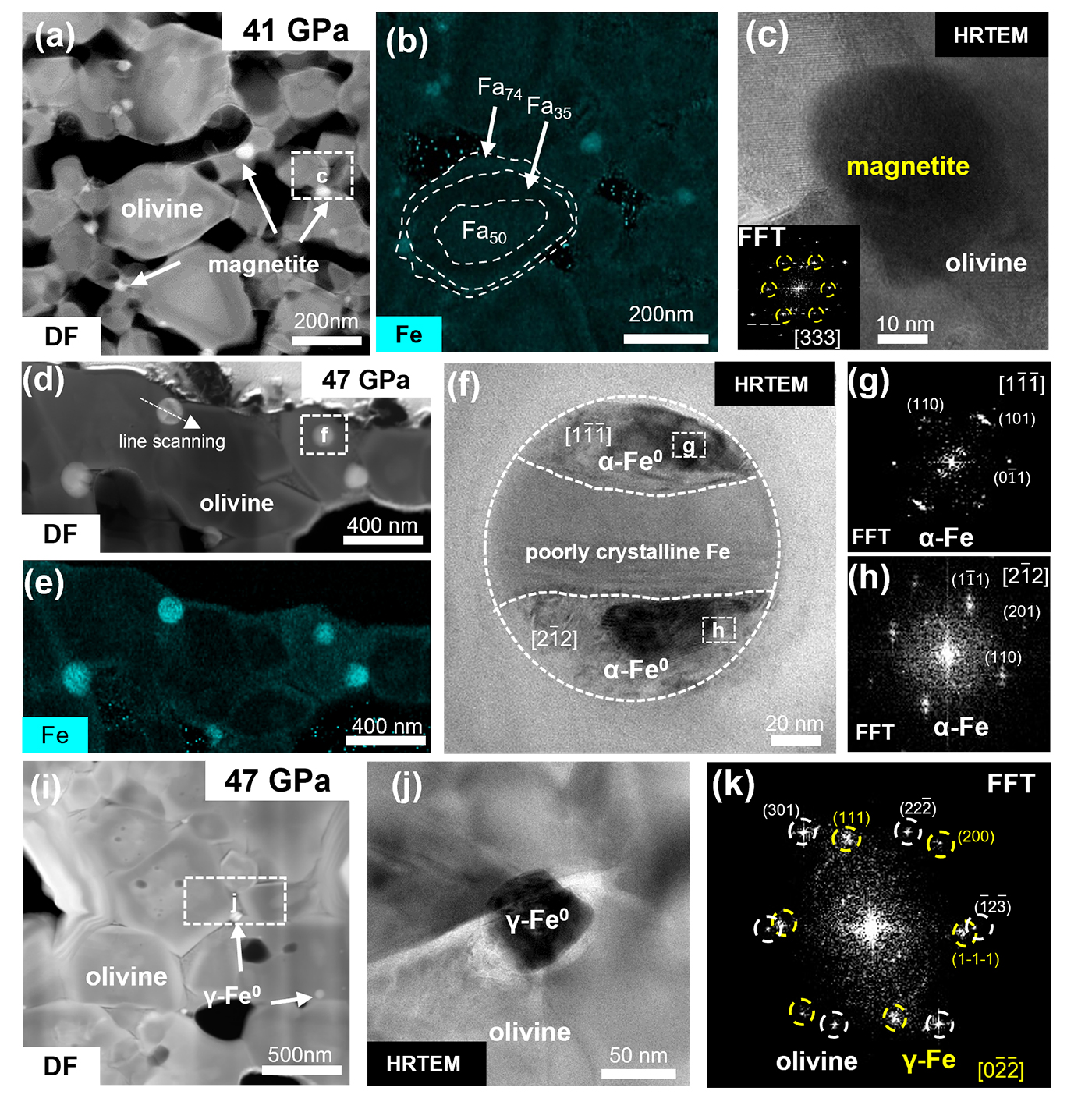

The shocked olivine samples exhibited systematic microstructural and spectral changes that varied with increasing shock pressure (Fig. 1). Shocked Fa50 olivine demonstrated shock-induced Fe migration and zoning at pressures ≥31 GPa, with the development of a three-layer Fe distribution pattern (core-intermediate-rim) accompanied by nanoscale α-phase (~120 nm) and γ-phase (20-50 nm) metallic iron particles. At shock pressures ≥41 GPa (corresponding to estimated transient temperatures ≥1185 K), minor magnetite particles (20–50 nm) were observed at olivine grain boundaries. Nanoscale vesicles, often associated with dislocations and grain boundaries, were also observed, indicating localized gas release. These phenomena indicate that magnetite can form not only through the direct decomposition of olivine but also via the oxidation of nanoscale metallic iron particles by oxygen vesicles generated during the impact process. Despite these extensive shock effects, no high-pressure olivine phases were detected, likely due to the short duration of the shock events.

There is a correlation between shock products and their spectral properties. Fa₅₀ olivine exhibited a reduced grain size, increased surface roughness, decreased crystallinity, and lower overall Fe content after impact. These structural changes resulted in 1) progressive peak shifts, increasing peak separation, and broadening of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) in the Raman spectra, indicating increasing structural disorder; 2) pressure-dependent trends, with increasing reflectance and spectral bluing at lower pressures (18 GPa), followed by reduced reflectance, redshifted absorption bands, and weakened absorption features at higher pressures (31-47 GPa) in the VNIR spectra. 3) Characteristic shifts in the Christiansen feature (CF) and Reststrahlen bands (RB1 and RB4) in the MIR spectra, particularly at pressures ≥31 GPa.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that impacts on Fe-rich silicates provide an alternative mechanism, independent of water-rock interactions, to influence the redox evolution of the Martian surface and the composition of its early atmosphere. Impact-induced nanoscale metallic iron, magnetite particles, and nanovesicles may directly contribute to the spectral reddening and localized bluing observed on the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos. However, longer cooling durations, more extensive Fe migration, and the formation of larger particles are more likely under natural conditions than under laboratory settings, highlighting the need for further experimental and observational studies focused on Martian moons.

Acknowledgements:This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 42441803, 42373042, 42422201, and 42003054). Youjun Zhang is supported by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant No. 2023NSFSC1910).

Figure 1: TEM images of metallic iron and magnetite particles. (a) and (b) Dark-field (DF) TEM image and iron elemental mapping of olivine shocked at 41 GPa. The Fe distribution within olivine exhibits a three-layer zoning pattern with average Fa# values of 50, 35, and 74 from the core to the rim. (c) High-resolution TEM (HRTEM) image of an iron-rich particle region in the sample shocked at 41 GPa. (d) DF image of olivine shocked at 47 GPa. (e) Fe elemental mapping of olivine shocked at 47 GPa, revealing that the nanoscale particles are iron rich. (f) HRTEM image of an iron particle with a diameter reaching 100 nm. The particles exhibit distinct contrast variations, divided into upper, middle, and lower regions, which are identified as α-Fe through fast Fourier transform (FFT) calibration. (g) and (h) FFT patterns of the upper and lower regions of the iron particle. (i) DF-TEM image of olivine shocked at 47 GPa. The nanoscale metallic iron particles are dispersed at the corners and edges of the grains and within the interior. (j) HRTEM image of an iron particle region in the sample shocked at 47 GPa. (k) FFT pattern of the iron particle shown in (c), confirming its identification as γ-phase metallic iron.

References

[1] Bibring, J., Ksanfomality, L., Langevin, I., et al., 1992, Adv. Space Res., 12(9): 13.

[2] Bagheri, A., Khan, A., Efroimsky, M., Kruglyakov, M., & Giardini, D., 2021, Nat. Astron., 5(6): 539.

[3] Canup, R., & Salmon, J., 2018, Sci. Adv., 4(4): eaar6887.

[4] Koeppen, W.C., & Hamilton, V.E., 2008, J. Geophy. Res.: Planets, 113(E5).

How to cite: Tai, K., Zhao, Y.-Y. S., Zhang, Y., Song, W., Yang, Y., Zhang, M., Qi, C., Du, W., Cao, F., Pang, R., Lin, H., Yin, Z., and Liu, Y.: Shock effects of Fa50 iron-rich olivine: Spectral and microstructural implications for Mars and Phobos, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-556, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-556, 2025.