- 1Institute of Geophysics of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Prague, Czechia (petr.broz@ig.cas.cz)

- 2Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Department of Geophysics, Prague, Czech Republic

- 3School of Geography and Planning, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK

- 4School of Physical Science, STEM, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK

- 5Space Science and Technology Department, STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Oxford, UK

The surfaces of many icy bodies in the Solar System have been resurfaced by cryovolcanism (e.g., Kirk et al., 1995; Porco et al., 2006; Roth et al., 2014; Küppers et al., 2014; Ruesch et al., 2019), during which liquid and vapour are released from the subsurface into cold, near-vacuum conditions. Such cryo-eruptions signal the presence of subsurface liquid reservoirs or oceans beneath the crust, and potential subsurface heat sources. Water is one of the most commonly released liquids, but it is not stable at low pressure – boiling near the water surface causes rapid cooling and induces surface freezing.

While signs of explosive cryovolcanism, including active plumes, have been observed on Enceladus, Triton, and likely on Europa, evidence for effusive cryovolcanism is rarer and harder to detect. The best examples are from Europa, where domes and smooth, ice-rich, low-albedo surfaces infill low-lying areas. However, since these features formed long ago and no active cryolava flows have been observed, it remains unclear how effusive cryovolcanism actually operates, limiting our ability to identify its imprints and products on icy moons.

Previously, it was proposed that effusive cryovolcanic flows would show similar structures to lava flow on Earth (Fagents, 2003). However, theory and experiments show liquid water experiences double instability in vacuum-like environments (e.g., Bargery et al., 2010; Quick et al., 2017; Brož et al., 2020a; 2023; Poston et al., 2024). Significant differences are thus expected between terrestrial and cryovolcanic lavas. The same is true of mud flows and ponded water bodies in low pressure environments when compared to their terrestrial counterparts (e.g., Allison and Clifford, 1987; Brož et al., 2020a,b; 2023; Morrison et al., 2022; Poston et al., 2024; Krýza et al., 2025). Previous laboratory experiments have worked with small volumes of liquid water (<500 ml) in small tubes (<2 cm radius) and thus were severely limited by the imposed boundary conditions (Bargery et al., 2010), or unable to show the processes taking place in a deeper water column (Brož et al., 2020a,b; 2023; Poston et al., 2024). This leaves many uncertainties about the behaviour of liquid water as it both freezes and boils at low pressure, in particular, how stable the ice crust is with respect to the forces that act to disrupt it.

To bridge this gap, we embark on a set of analogue experiments using a low-pressure chamber at the Open University in the UK (Fig. 1). Our objective was to study the behaviour of a large quantity (from ~17 to ~40 l) of water experiencing phase transitions under a low-pressure environment. We also focused on the rate of water evaporation (loss to space), and investigated the impact of salt concentrations on the freezing dynamics and resulting ice characteristics – specifically how it affects the freezing and boiling points as well as how the salt crystals interact with the ice crystals. Thermocouples were placed at different depths in the containers to observe the temperature of the water at those points. We further ran these experiments for an extended time (~8 hours) to explore the effects of long-term cooling on the water.

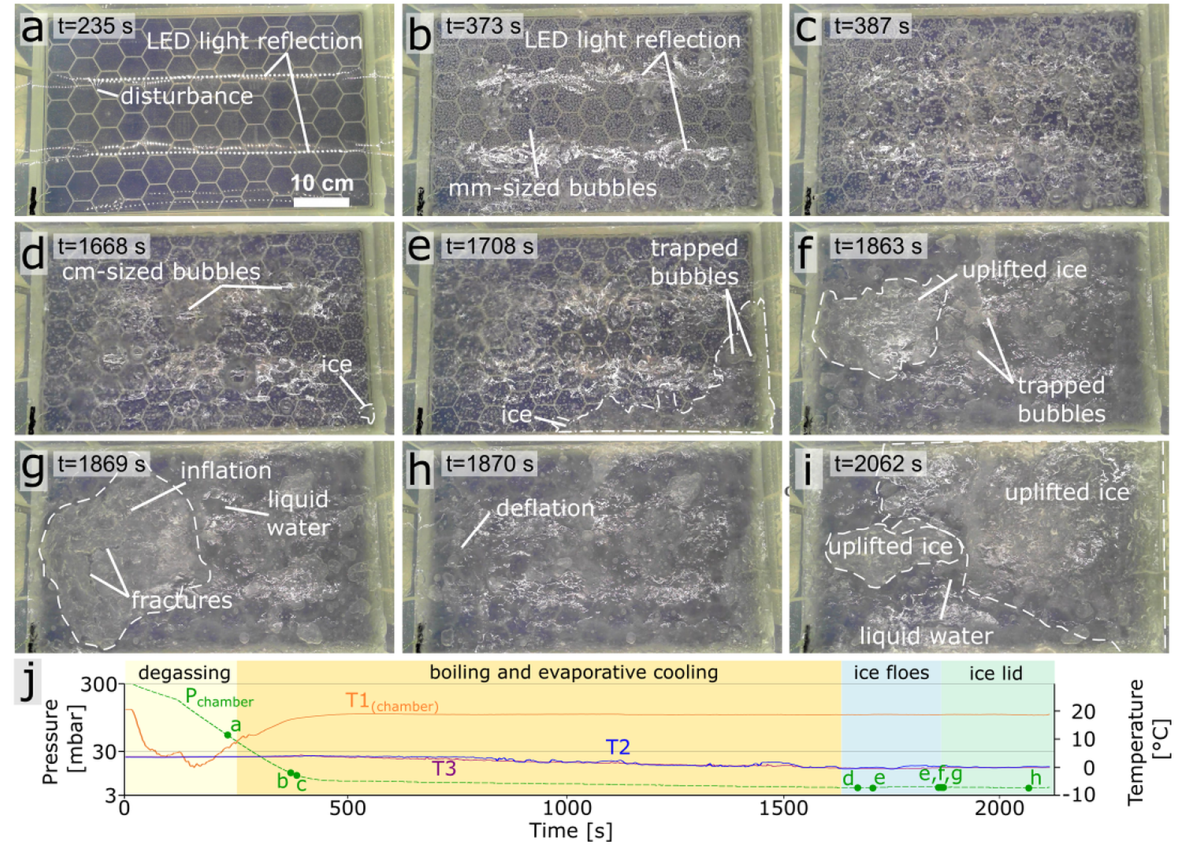

Figure 1: Images from various time points (a-i) illustrating the behavior of liquid water under low atmospheric pressure. When pressure dropped below the saturated vapor pressure (j), vigorous boiling began, reducing the temperature to the freezing point. Floating ice formed and gradually covered the tank, but continued boiling fractured and lifted the ice crust, delaying full surface freezing.

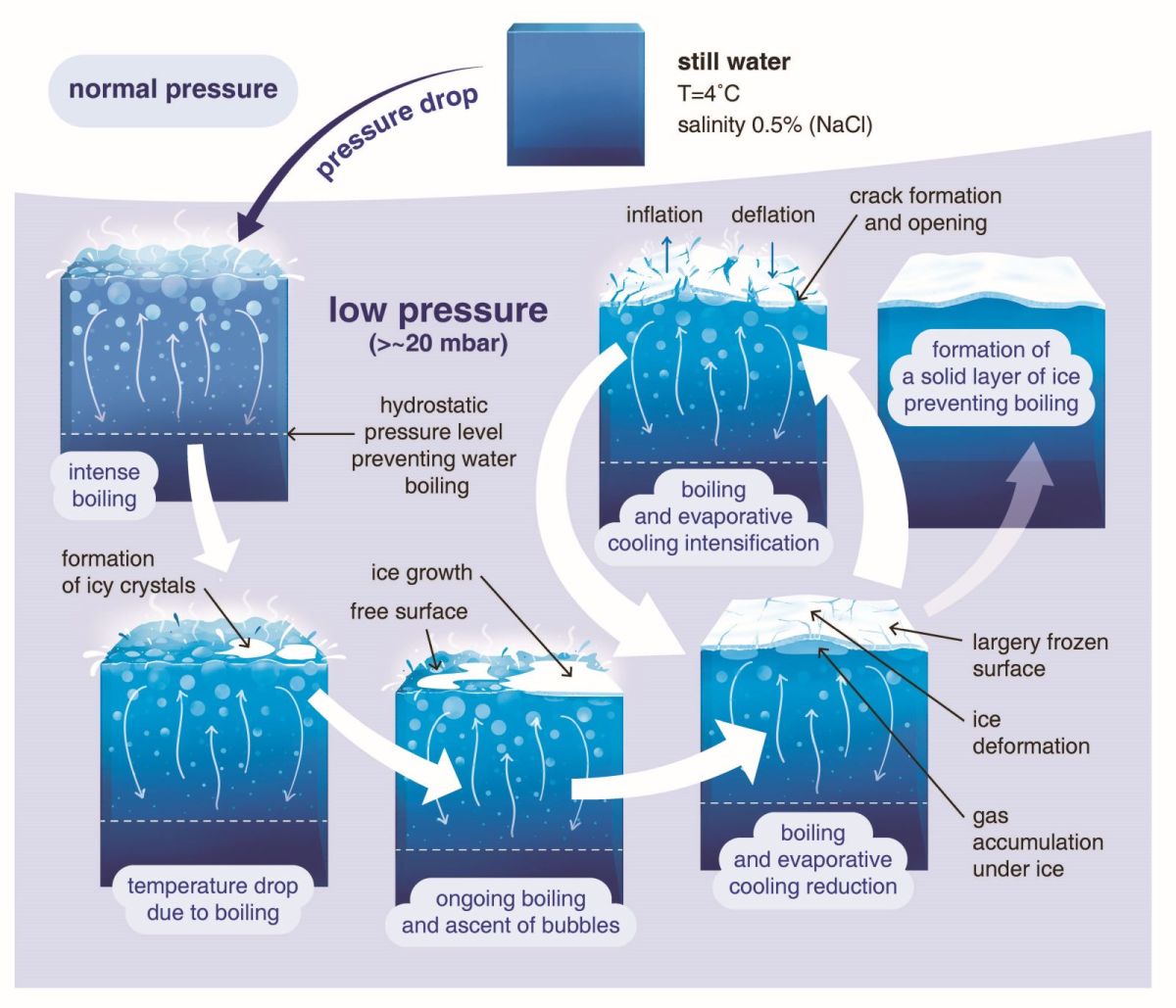

We observe that subsurface boiling and associated bubble formation significantly affects the rate and manner of freezing (Fig. 2). Ascending vapour deforms the ice and causes it to crack, which releases subsurface pressure. Once the pressure is released, the underlying liquid water is again exposed to the reduced atmospheric pressure, triggering a new cycle of vigorous boiling, bubble formation, ice deformation, and subsequent cracking. Thereby, the period of boiling and freeze-over is prolonged compared to a scenario more typical of terrestrial environments where boiling-induced cracking does not occur. Additionally, we observe that fracturing and vapour accumulation beneath the ice layer create an uneven surface, characterized by bumps and depressions a few centimetres in height. This shows that ice solidification during effusive cryovolcanic eruptions is likely to be a highly complex process and could leave distinct, observable signatures on and within cryolava ponds and flows.

Figure 2: Schematic model showing the main phases associated with the phase transition of water under reduced atmospheric pressure.

We plan to complement these laboratory analogue experiments with numerical modelling (currently we are considering using the code StagYY with modifications to account for visco-elasto-plastic rheology; Patočka et al., 2017) to explore the physics of the observed processes and further extrapolate our experimental observations to planetary environments with various gravitational and atmospheric conditions.

The work presented herein contributes to an overarching aim is to discover how initial boiling and internal pressure of water influences ice crust stability during effusive cryovolcanic eruptions on planetary bodies that lack a substantial atmosphere. This research has direct relevance to forthcoming exploration missions such as NASA's Europa Clipper and ESA's JUICE, and broader implications for the study of water stability on Mars.

References:

Allison and Clifford (1987), J. Geophys. Res., 92; Brož et al. (2020a), Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 545, 116406; Brož et al (2020b), EPSL 545; Brož et al. (2023), JGR-Planets 128; Fagents (2003) J. Geophys. Res. 108 (E12); Kirk et al. (1995), Neptune and Triton, vol. 1, 949–989; Krýza et al. (2025), Communications Earth and Environment 6, 116; Küppers et al. (2014), Nature 505 (7484); Morrison et al. (2022), JGR-Planets 128; Patočka et al. (2017), Geophys. J. Int., 209(3); Porco et. Al (2006), Science 311 (5766); Roth et al. (2014); Science 343 (6167), Ruesch et al. (2019), Nature Geoscience, 12(7).

Acknowledgements: This work was funded by the Czech Grant Agency grant No. 25-15473S.

How to cite: Biju Sindhu, P., Broz, P., Patočka, V., Butcher, F., Fox-Powell, M., Sylvest, M., Emerland, Z., and Patel, M.: Experimental Insights into the Phase Transitions of Water in Low-Pressure Environments, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-585, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-585, 2025.