- 1Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Lisbon, Portugal (jeosilva@fc.ul.pt)

- 2Institute for Basic Science, Daejeon, Korea, Republic of

- 3Departamento de Fisica Atomica, Molecular y Nuclear, Facultad de Fisica, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain

- 4Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, Japan

- 5LATMOS-IPSL, Paris, France

- 6Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal

- 7European Space Astronomy Centre, Madrid, Spain

- 8Institute of Astrophysics of Andalucia, Glorieta de la Astronomía, Granada, Spain

- 9Faculty of Science, Kyoto Sangyo University, Kyoto 603-8555, Japan

Venus is a planet that has garnered renewed interest in recent years. Regarded as Earth’s twin, as it shares many of its basic properties with our home in the Solar System. However, upon close inspection, similarities between the two planets end, whose present conditions in contrast to Earth expose how different the evolution of Venus must have been. Many unanswered questions remain regarding the process that led to Venus’ current conditions, which have motivated at least one future space mission towards the planet in the 2030’s, EnVision. In the meantime, it continues to be an exciting target for new discoveries as we try to peer deeper into our neighbouring planet.

The atmosphere of Venus is on such subject of continuous research, with a thick layer of clouds speeding around the globe in approximately four days in its uppermost regions. Approximately 90 times as massive as Earth and mostly composed of carbon dioxide, its lower troposphere and near-surface conditions are extremely challenging to access with remote observations. However, processes that are observable in the cloud layer between roughly 50-70 km of altitude manifest a tentative connection to the surface. One of these is the presence of stationary features which seem correlated with prevalent topography on the surface.

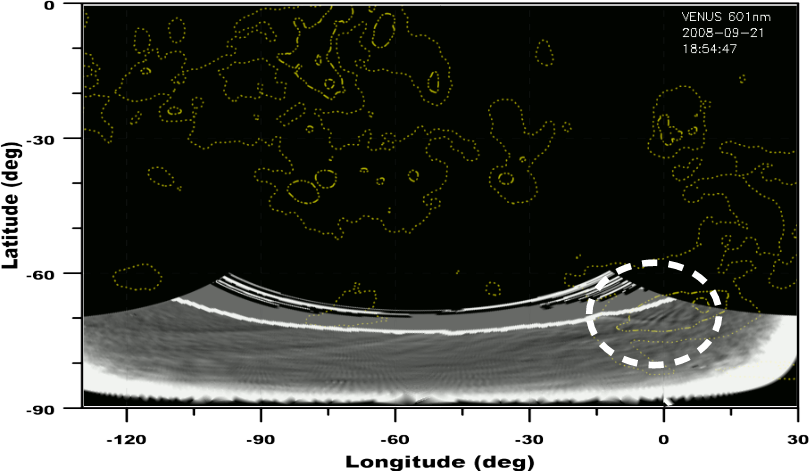

In the past decade, bow-shaped stationary features jumped to the spotlight with the observation of a planetary scale feature by the Japanese space mission Akatsuki in December 2015 [Fukuhara et al. 2017]. Further detections by ESA’s Venus Express mission between 2006-2008 [Peralta et al. 2017] reinforced these findings. Several instruments onboard Akatsuki have thus far provided a continuous cover of the planet’s cloud layer, including further detection and characterization of stationary features on the top of the clouds with the Ultraviolet Imager (UVI) [Kitahara et al. 2019] which is sensitive to ultraviolet radiation, and at slightly lower levels thanks to the capabilities of the Longwave Infrared Camera (LIR) [Fukuya et al. 2022] which senses the thermal emission from the upper clouds at mid-infrared. Such features have also been reported using the IR2 camera [Sato et al. 2020], using dayside observations at 2.02 microns sensitive to one of the CO2 absorption bands. Most of these features have been interpreted as a form of atmospheric gravity wave, in this case generated by flow over prominent topography.

Gravity waves are periodic perturbations in which the buoyancy of the perturbed fluid acts as the restoring force. These waves require a forcing mechanism to be generated, and a statically stable environment so that they can propagate through the fluid in which they are generated. Given that their properties allow them to carry energy and momentum across the atmosphere, especially in the vertical direction, they become a crucial subject matter for atmospheric science. For the case of Venus, they represent a good opportunity to investigate the conditions in which objects like stationary waves might form, and if they are of orographic origin. As they are observed in the cloud layer of Venus, which for dayside visible and mid-infrared observations usually represents a region between 60-70 km of altitude, they may establish a link between the cloud layer and the surface. However, a positive static stability environment, which is necessary for the propagation of these waves, does not seem to always be verified between the surface and the cloud layer. There lies the puzzle of explaining the existence of such phenomena in the cloud layer, although considerable efforts have already been directed in this front with some success, through atmospheric modeling [Imamura et al. 2018, Lefèvre et al. 2020]. Several of these efforts mention the need for extended observations of these features for a more robust interpretation of the generation and propagation of stationary waves on Venus.

We present here a contribution in this front, taking advantage of data from multiple instruments to detect and characterise stationary features which resemble gravity waves on the dayside of Venus. We used data from the VIRTIS instrument onboard the Venus Express mission, using multiple wavelengths that can detect contrasting features in the clouds at several levels of the cloud layer. To complement this selection, we used data from the IR2 instrument with the 2.02 micron filter, following up on previous observations and performed a reanalysis of the structures reported in Kitahara et al. (2019) detected most strongly at 283 nm with the UVI instrument. To our surprise the distribution of features does not seem to be completely correlated with noteworthy topography and some exhibit morphologies that have not been documented for waves of this kind on Venus. The length scales of the new features are in the mesoscale range with horizontal wavelengths mostly between 100-200 km, and whose properties are in good agreement with previous studies of this phenomena on Venus, albeit with an arguably more diverse range of shapes and a wider geographical distribution and local time.

References

Fukuhara et al. 2017, Nat. Geoscience; DOI: 10.1038/NGEO2873

Fukuya et al. 2022, Icarus; DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2022.114936

Imamura et al. 2018, JGR Planets; DOI: 10.1029/2018JE005627

Kitahara et al. 2019, JGR Planets; DOI: 10.1029/2018JE005842

Kouyama et al. 2017, Geophys. Res. Lett.; DOI: 10.1002/2017GL075792

Lefèvre et al. 2020, Icarus; DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2019.07.010

Peralta et al. 2017, Nat. Astronomy; DOI: 10.1038/s41550-017-0187

Sato et al. 2020, Icarus; DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2020.113682

How to cite: Silva, J., Peralta, J., Imamura, T., Lefèvre, M., Machado, P., Cardesín, A., Ando, H., Brasil, F., Espadinha, D., and Joo Lee, Y.: Cross-Instrument stationary features on Venus’ dayside atmosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-595, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-595, 2025.