- 1Space Research & Planetary Sciences, Physics Institute, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland

- 2Department of Aerospace Science and Technology, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy

Circumasteroidal debris disks offer an explanation for the surprising existence of atypically shaped binary asteroid satellites [1], such as the oblate Dimorphos imaged by NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) spacecraft [2], or the contact binary satellite Selam detected by Lucy [3]. Classical theories based on the slow build-up of material in orbit around a rapidly spinning primary [4] or contact binary fission [5] account for the predominantly prolate (elongated) population [6], but not any outlier structures. In our work, we used polyhedral N-body simulations to show that the dynamical environment of debris disks around rubble pile asteroids produces mergers between moonlets in the unexplored sub-escape-velocity regime which can create a wide range of unusual satellite shapes.

Spinning rubble pile asteroids only held together by gravity structurally fail before any wide debris disk can be formed, but adding a small amount of cohesion can allow them to reach significantly higher spin rates [7], leading to more chaotic mass-shedding events. Just a few per cent of the primary mass in a disk extending beyond the fluid Roche limit is enough to generate multiple moonlets of varying sizes that dynamically interact and merge [1]. More eccentric orbits are dampened by the surrounding matter, causing mergers to occur with small impact angles. As the typical impact velocity is proportional to the ratio between the total mass of the moons and the mass of the primary [8], the observed impact velocities in simulations of this scenario are always lower than the mutual escape velocity of the moonlets [1].

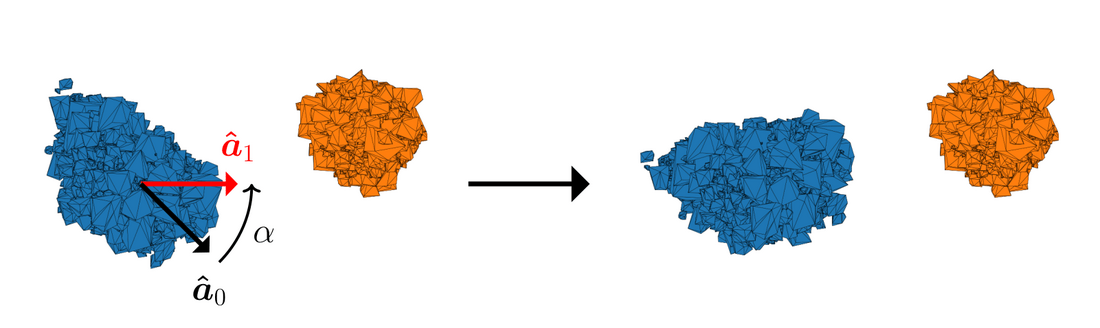

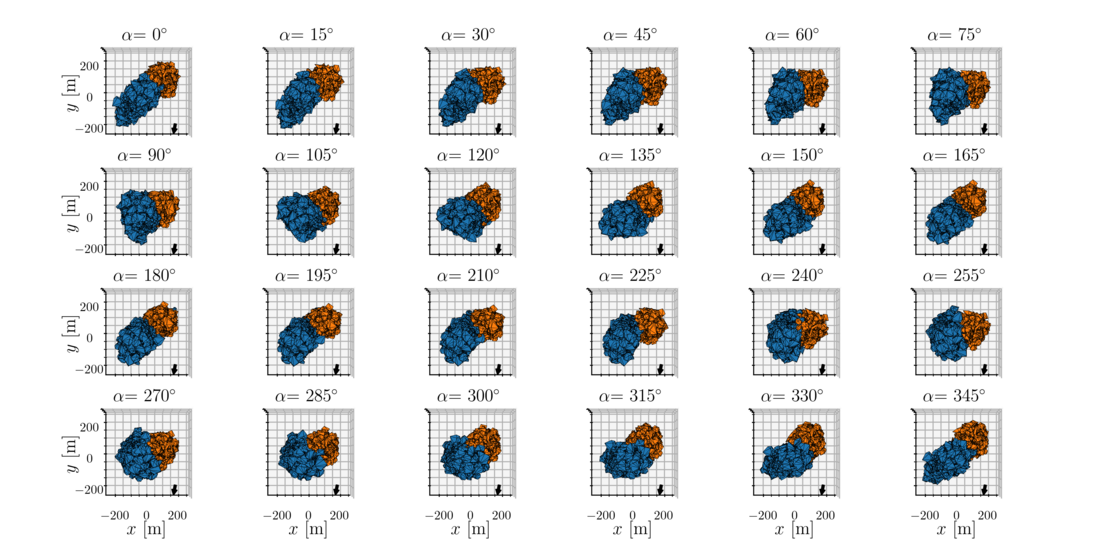

Because of the soft impacts, the initial shape of the participating moonlets is largely retained, with the most massive specimen being prolate due to tidal distortion. To show that the final shape is highly dependent on the relative orientation of the two bodies and the location of the impact, we performed a set of simulations based on a merger observed in a debris disk scenario (see [1]). Keeping the impact angle, velocity, spin rate, and position of the merger intact, we rotated the most massive body in the equatorial plane of the primary around its barycenter by different angles α to generate a set of new configurations, illustrated in Figure 1. As expected, each merger led to a unique shape, as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1: Alteration of the initial merger configuration seen on the left side by rotating the largest moonlet (blue) by some angle α, generating new initial conditions [9].

Figure 2: Post-merger shapes of the merged moonlets, where α indicates the counterclockwise rotation of the largest moonlet (blue) with respect to the original configuration of the merger [9]. The black arrow indicates the direction of the primary.

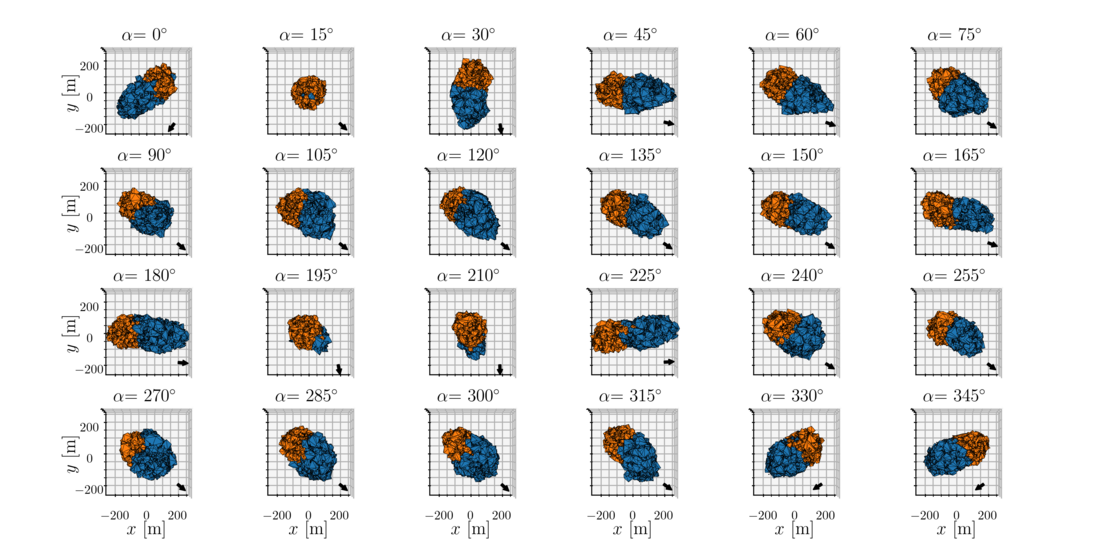

Letting the system evolve for a few orbits, we found that each body deformed with varying degrees via tidal disruption and distortion, depending on the initial shape and spin-orbit state of the body. Elongated objects were more susceptible to disruption, leaving only the outer lobe intact on a hyperbolic orbit. On the other hand, the more compact objects would instead undergo partial mass-shedding. To consistently have moons survive the tidal disruption stage, we increased the post-merger distance from the primary by 10%. Among the resulting shapes in Figure 3, we can identify spherically oblate Dimorphos-like (α = 15°) and elongated, bilobate Selam-like objects (α = 225°).

Figure 3: The shapes of the moons in Figure 1 after 48 h of simulation, for the case where their post-merger distance from the primary was increased by 10% [9].

Our results further reinforce the idea that objects like Dimorphos and Selam have formed in circumasteroidal debris disks and further hint at the existence of other, atypically shaped binary asteroid satellites born from sub-escape-velocity mergers. With the upcoming ESA Hera mission that will revisit the Didymos system [10], along with future space missions visiting binary asteroid systems, we can constrain moon shapes and develop our understanding of the underlying formation mechanisms at play.

Acknowledgments

J.W. and F.F. acknowledge funding from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) Ambizione grant No. 193346. M.J. acknowledges support from SNSF project No. 200021_207359.

References

[1] Wimarsson et al. Icarus, 421, 116223, 2024

[2] Daly et al. Nature, 616(7957):443–447, 2023

[3] Levison et al. Nature, 629, 1015, 2024

[4] Walsh et al. Nature, 454(7201):188–191, 2008

[5] Jacobson and Scheeres. Icarus, 214(1):161–178, 2011

[6] Pravec et al. Icarus, 267, 267, 2016

[7] Hirabayashi et al. ApJ, 808(1):63, 2015

[8] Leleu et al. Nature Astronomy, 2, 555, 2018

[9] Wimarsson et al., submitted, 2025

[10] Michel et al. PSJ, 3(7):160, 2022

How to cite: Wimarsson, J., Ferrari, F., and Jutzi, M.: Forming unusually shaped moons in binary asteroid systems via sub-escape-velocity mergers and tidal deformation, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-790, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-790, 2025.