- 1Technische Universität Berlin, Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation Science, Berlin, Germany (wladimir.neumann@tu-berlin.de)

- 2Macau University of Science and Technology, Avenida Wai Long, Taipa, Macau

- 3Bayerisches Geoinstitut, Universität Bayreuth, 95447 Bayreuth, Germany

- 4Department of Earth Sciences, Institute of Earth and Space Exploration, University of Western Ontario, N6A 5B7 London, Ontario, Canada

- 5Institut für Geowissenschaften, Klaus-Tschira-Labor für Kosmochemie, Universität Heidelberg, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

Introduction

Angrites are differentiated rocky meteorites that are distinct form other achondrites in their oxygen isotopic compositions and originate from a planetary object that formed in the inner solar system. Crystallization ages of up to ≈4.564 Ga make the angrites the oldest igneous rocks of the solar system and their material indicates heating of the parent body to high temperatures sufficient for melting and differentiation. This implies an early parent body accretion relative to the formation of Ca-Al-rich inclusions (CAIs) and possibly a big size. Quenched angrites cooled rapidly on the surface, while plutonic angrites cooled in the interior of the crust or mantle. While asteroids with diameters of up to 60 km can be related to angrites based on their reflectance spectra[1-4], the parent body could not be identified in the present solar system, implying its destruction in the past. An upper bound on the size for this object is provided by the size of Mars[5]. In particular, Mercury has been discussed as the source of the angrites[6-9]. Here, we combine thermo-chronological data with thermal evolution modeling to constrain the accretion time and size of the angrite parent body.

Data and methods

The thermo-chronological data, such as cooling ages and closure temperatures, can be combined with thermal evolution models and help constraining not only the accretion time and internal evolution, but also the size of the parent body[10]. We combine new[11] and literature data (long-lived and short-lived chronometers in mineral phases, such as Pb-Pb, Al-Mg, Mn-Cr, Hf-W, and U-Pb phosphate ages) with numerical modeling to derive constrains on the angrite parent body. The ages and corresponding closure temperatures result in 31 data points for 13 meteorites in total, of which 12 data points are from 5 quenched angrites (Sahara 99555, NWA 1670, NWA 10463, NWA 2999, NWA 6291) and 19 data points from 8 plutonic angrites (D´Orbigny, Angra Dos Reis, Asuka 881371, NWA 1296, NWA 4590, NWA 4801, LEW 86010, NWA 8535). We considered two cases: (a) data for both quenched and plutonic angrites, and (b) data for plutonic angrites only. We calculated thermal evolution models for planetesimals of varying accretion times and sizes and fitted temperature evolution curves at different depths to the data with an RMS procedure[10,12-14]. The best-fit parent bodies and best-fit depths for the meteorites within a parent body were identified.

Results and Conclusions

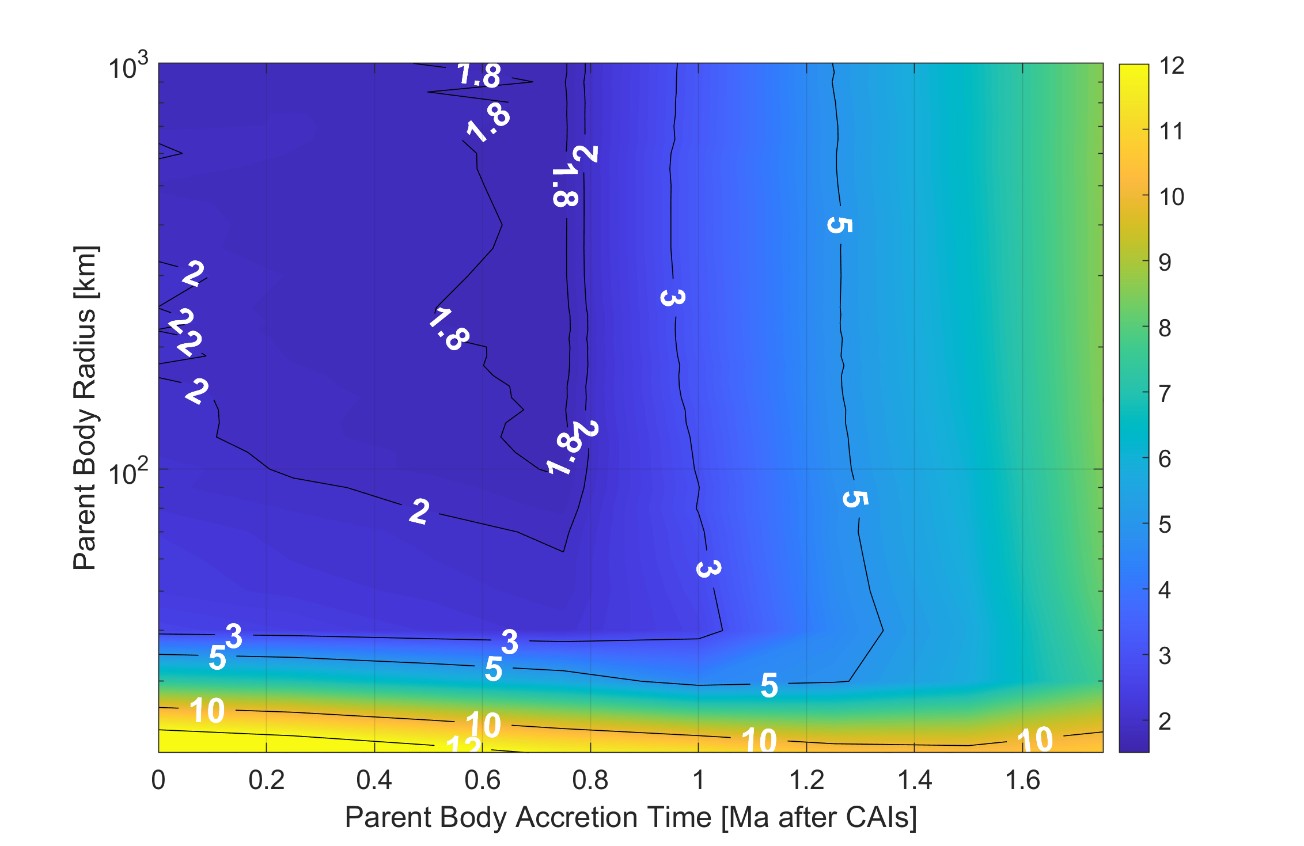

A fit is considered to be acceptable if the fit quality χ2 is limited by the difference between the number of data points N and number of the optimized parameters p: χ2 < N-p. Here, assuming that different meteorites originate from different depths, p is the number of these fitted depths plus the number of the global parent body properties fitted (radius and accretion time). This means χ2 < 14 or χ< 3.7 for case (a) (omitting two outliers – Angra Dos Reis U-Pb phosphate and NWA 4801 U-Pb phosphate) and χ2 < 8 or χ< 2.8 for case (b). In both cases, we could identify planetesimals that satisfy this condition. The overall fit quality as a function of the planetesimal radius and accretion time takes minimum values of χ< 1.8 (see Fig. 1 for case (a)) for an accretion close to 0.6 – 0.8 Ma after CAIs and a radius of at least 100 km. However, no upper bound on the radius could be constrained.

Figure 1: The fit quality χas a function of planetesimal accretion time t0 (abscissa) and radius R (ordinate). Best fits of χ< 1.8 are obtained for t0 of 0.6 to 0.8 Ma and R > 100 km.

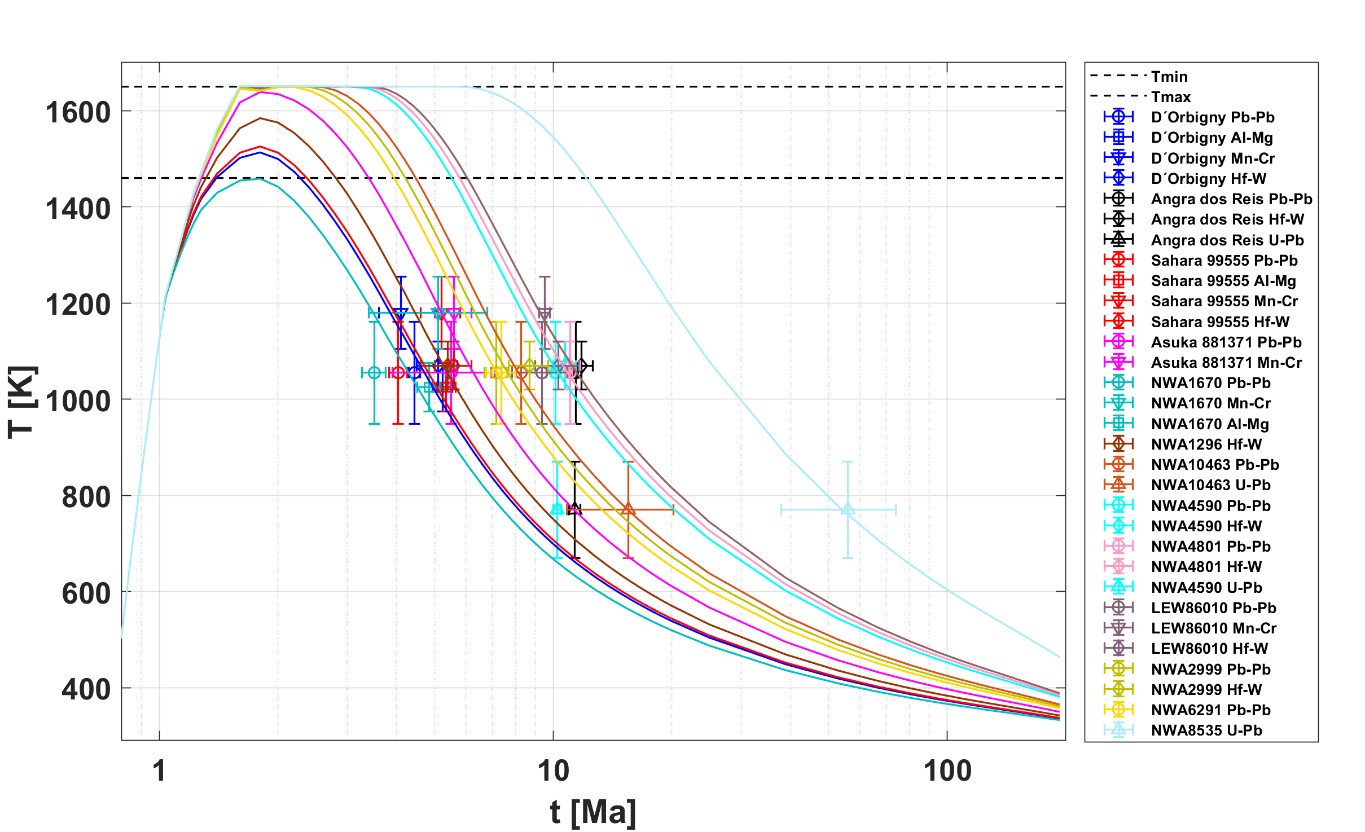

Figure 2 shows thermal evolution curves at the fit depths of the meteorites for a representative planetesimal with R = 200 km and t0 = 0.75 Ma. NWA 8535 is fitted at the highest depth of 19 km relative to other meteorites (2.7 km – 9.5 km). The cooling rates calculated between the temperature maxima and the lowest closure temperature (600 K for U-Pb in phosphates) are inversely proportional to the fit depths, with the highest value of ≈80 K/Ma for NWA 1679 fitted at ≈2.3 km, decreasing to ≈50 K/Ma for LEW 86010 and Angra Dos Reis both fitted at ≈9.5 km, and with the lowest being ≈10 K/Ma for NWA 8535 fitted at ≈19 km.

Omitting quenched angrites, but including the outliers and fitting them at separate depths assuming extrusion from a deeper interior to shallower depths (case (b)) leads to a better fit quality. However, the depth range and the cooling rates remain similar. In particular, the late NWA 8535 U-Pb phosphate age requires very slow cooling of the deeper crust or upper mantle of ≈10 K/Ma and, thus, favors a big parent body with a radius of > 100 km.

Our results constrain the accretion time of the angrite parent body to a narrow time interval of 0.6 Ma to 0.8 Ma after CAIs and confirm that it was one of the larger asteroids, if it was an asteroid at all. However, the fit quality improves with an increasing radius and, thus, allows for a planet-size parent body.

Figure 2: Thermal evolution curves at the fit depths of the meteorites for case (a) and a representative planetesimal with R = 200 km and t0 = 0.75 Ma.

[1] Burbine et al. (2001) 32nd LPSC, 1857.

[2] Burbine et al. (2006) MAPS 41, 1139-1145.

[3] Rivkin et al. (2007) Icarus 192, 434-441.

[4] Rider-Stokes et al. (2025) Icarus 429, 116429.

[5] Baghdadi et al. (2013) MAPS 48, 1873-1893.

[6] Irving et al. (2005), Eos, 86, P51A-0898.

[7] Kuehner and Irving (2006). 38th LPSC, 1344.

[8] Ruzicka and Hutson (2006) MAPS 41, Proceedings of 69th MetSoc Annual Meeting, 5080.

[9] Blewett and Burbine (2007) 38th LPSC, 1203.

[10] Neumann et al. (2018) Icarus 311, 146-169.

[11] Bouvier et al. (2024) 86th MetSoc Annual Meeting (LPI Contrib. 3036), 6210.

[12] Neumann W. et al. (2023) PSJ 4, 196.

[13] Neumann et al. (2024) SciRep 14, 14017.

[14] Ma M. et al. (2022) GPL 23, 33-37.

How to cite: Neumann, W., Bouvier, A., Reger, P., and Trieloff, M.: Formation Time, Thermal Evolution, and Size of the Angrite Parent Body, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-839, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-839, 2025.