- 1Purdue University, Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, United States of America (sperezco@purdue.edu)

- 2Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD, United States of America

- 3University of Maryland / NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD, United States of America

- 4Smithsonian Institution, National Air and Space Museum, Washington DC, United States of America

- 5Planetary Science Institute, Tucson, Arizona, United States of America

1. Introduction

Secondary craters result from the impact of primary ejecta falling back to the surface. Closer to the primary crater, secondaries form at low velocities and show asymmetric shapes (McEwen et al., 2005; Pike & Wilhelms, 1978; Oberbeck & Morrison, 1973; Melosh, 1989), while farther away, higher-velocity ejecta produce secondaries resembling small primaries (Bart & Melosh, 2007). This range-induced morphologic diversity creates a challenge in distinguishing simple primaries from distant secondaries, affecting crater-chronology accuracy (McEwen & Bierhaus, 2006).

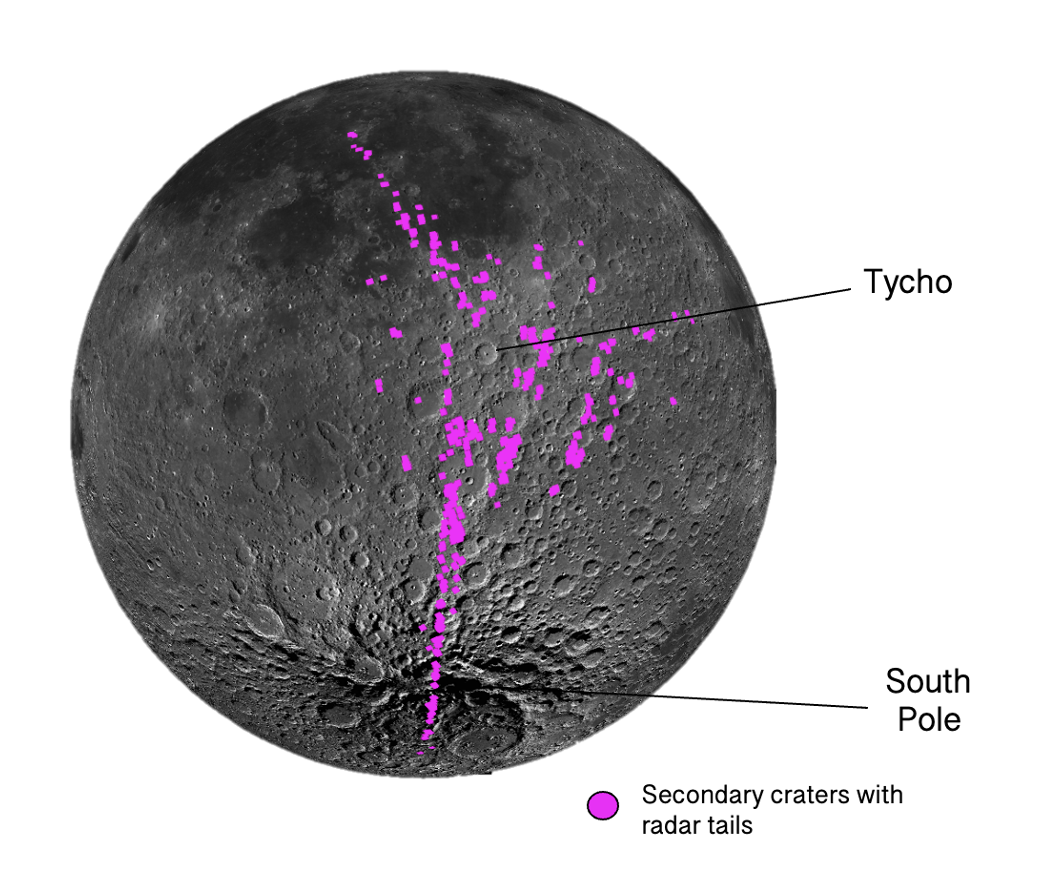

On the Moon, radar studies have found that some small craters exhibit radar-bright, asymmetric ejecta that is enhanced in cm- to dm-scale debris and may be attributed to secondary formation. Specifically, potential secondaries with ejecta extending downrange from Tycho crater have been identified within Tycho’s rays (Wells et al., 2010; Watters et al., 2017), including over the South Pole and intersecting Haworth, a potential Artemis landing site (Rivera-Valentín et al., 2024). Here, we used multiple datasets from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), including Mini-RF radar observations, to catalog and characterize Tycho secondaries along its rays. Our goal is to investigate the causes of these radar-bright, asymmetric ejecta deposits (termed “radar tails”) and explore their implications for secondary and ray formation processes.

2. Methods

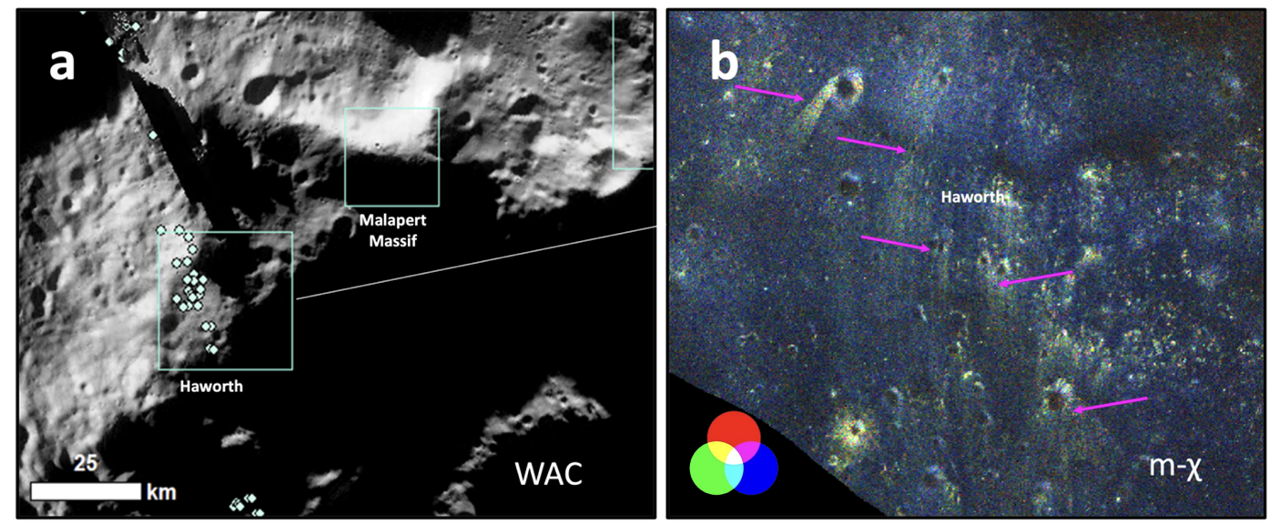

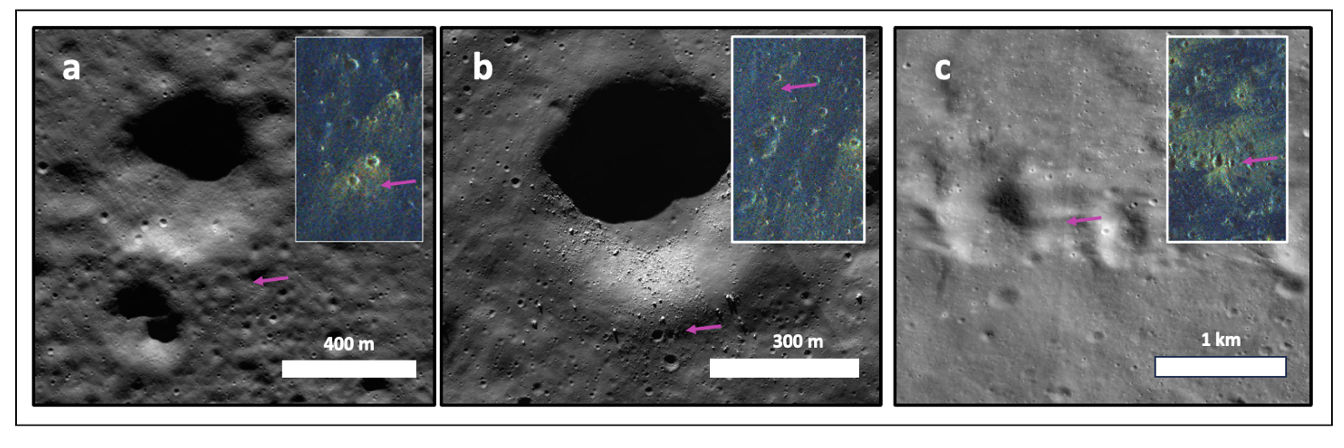

Potential secondary craters along several of Tycho’s rays (Fig. 1) were first identified in radar imagery via the presence of a radar-bright, asymmetric ejecta signature oriented away from Tycho. We used S-band (12.6 cm) monostatic radar data from LRO Mini-RF, a hybrid-polarimetric SAR. Data products analyzed included circular polarization ratio (CPR) and m-chi decomposition images (Raney et al., 2012). The m-chi RGB composite displays even-bounce (red), random (green), and odd-bounce (blue) scattering.

Figure 1: Distribution of Tycho secondary craters with radar-bright extended asymmetric ejecta deposits (“radar tails”) identified in this study.

In addition to our radar characterization, we measured the depth and diameter for each potential secondary crater using LOLA elevation data (Barker et al., 2016) and calculated depth-to-diameter (d/D) ratios. The same method was applied to nearby primary craters (>300 m in diameter, without radar-bright ejecta tails) for context.

To study the morphology of secondary craters and understand the cause of the ejecta tails observed in the radar products, we then used both LROC NAC images and ShadowCam images to describe the surface texture of the radar tails and document the presence of boulders and assessed the maturity of the craters.

3. Results

We identified 473 craters in Tycho’s South Polar ray, including 24 secondaries at Haworth (Fig. 2, candidate landing site for the Artemis missions), and 543 more secondaries in the other bright rays. Tycho secondaries at Haworth could offer a chance to sample Tycho ejecta and compare it to Apollo 17 material (Jolliff et al., 2020; Rivera-Valentín et al., 2024).

Supporting our interpretation that the craters with radar tails are secondary craters is the observation that radar tail craters have lower d/D ratios (~0.04) than primaries (~0.10) identified in the same area. Preliminary crater size-frequency distribution analysis also supports this interpretation.

Figure 2: Tycho secondary craters with extended asymmetric ejecta (magenta arrows) in Haworth.

We find that Tycho secondary craters exhibit three possible classes of extended asymmetric ejecta: (1) isolated secondaries (only one radar-bright tail extends from the crater), (2) clusters (multiple tails merge into one emanating from a cluster of craters), and (3) linear crater chains (closely spaced craters arranged roughly straight line). We observed that the enhanced depolarized backscatter signals associated with the radar tails can be attributed to three main factors: (1) subsurface scattering likely caused by buried structures, such as subsurface blocky material or debris (based on the lack of observed surface features on visual images, (2) scattering from surface boulders, and (3) presence of craters (with D>200m) along the radar tail.

Figure 3: We found 3 main tail textures that could be causing the depolarized scattering (a) buried structures, (b) surface boulders, (c) additional craters.

4. Conclusions

We confirm that radar data can be used to identify fresh secondary craters on the Moon via the presence of extended, asymmetric radar-bright ejecta "tails" that trace surface roughness and subsurface scatterers. These tails, aligned with topography and pointing away from the primary impact site, may reflect ejecta debris flow processes, such as a debris surge (Campbell et al., 1992; Wells et al., 2010; Watters et al., 2017). Radar features often extend beyond visible surface textures, suggesting that much of the structure lies beneath the surface. Radar datasets are therefore uniquely placed to examine secondary processes.

References:

- Barker et al. (2016). Icarus, 273, 346–355.

- Bart and Melosh. (2007). Geophysical Research Letters, 34(7).

- Jolliff et al. (2020). 54th LPSC 2023 (LPI Contrib. No. 2806).

- McEwen & Bierhaus (2006). Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 34, 535–567.

- Melosh (1989). Impact cratering: a geologic process. New York: Oxford University Press; Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Oberbeck et al. (1973). The Secondary Crater Herringbone Pattern, 4, 570.

- Pike & Wilhelms (1978). Secondary-Impact Craters on the Moon: Topographic Form and Geologic Process, 907–909.

- Raney et al. (2012). JGR: Planets, 117(E12).

- Rivera-Valentín et al. (2024). PSJ 5(4), 94

- Watters et al. (2017). JGR: Planets, 122(8), 1773–1800

- Wells et al. (2010), JGR: Planets, 115, E06008

- Martin-Wells et al. (2017). Icarus, 291, 176-191

How to cite: Perez-Cortes, S., Rivera-Valentin, E., Ahrens, C., Bramson, A., Fassett, C., Nypaver, C., Morgan, G., and Patterson, W.: Characterization of Tycho Secondary Craters on the Moon Using LRO Mini-RF Radar Data: Implications for Formation Mechanisms, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-861, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-861, 2025.