- Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada (benaroya@ualberta.ca)

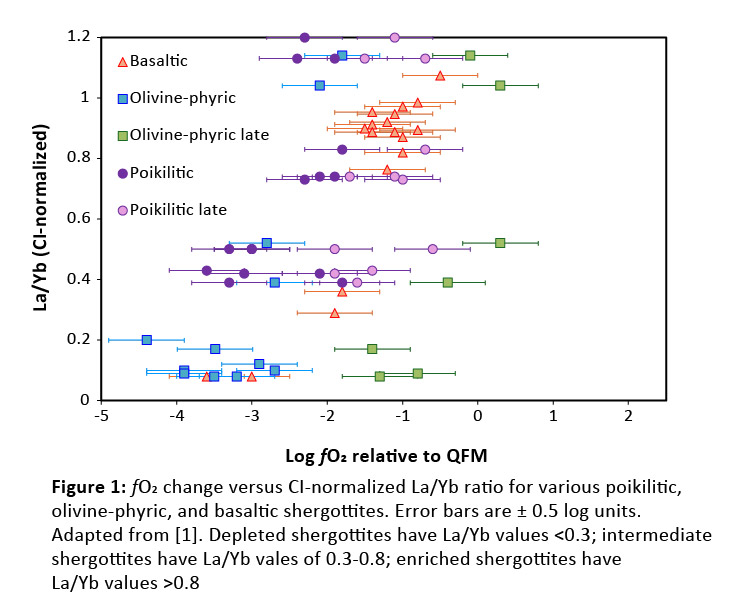

Introduction: Martian meteorites are currently the only samples on Earth available to study Mars. These samples comprise mainly (>80% by number) shergottite-type rocks, which are basaltic to lherzolitic [1]. Shergottites provide valuable information regarding the conditions of the martian interior, including its chemical composition and redox state. The redox state of shergottites of various petrologic types has been estimated (Fig. 1), and there appears to be a correlation between oxidation state and relative enrichment/depletion of incompatible trace elements (ITEs), with rocks that are enriched in ITEs also being more oxidized. An additional observation is that shergottites undergo extensive oxidation during their formation [2-4], with an increase in fO2 of 1-3 log units. Auto-oxidation can increase fO2 by a maximum of ~0.5 log units [3, 5] and thus cannot solely explain this change. Degassing of volatiles had been suggested as an alternative mechanism to oxidize these rocks [2-6]. Recent studies on the solubility of C, S, and H species in martian compositions [7-12], have allowed for Mars-appropriate degassing models to be developed, like Magma and Gas Equilibrium Calculation (MAGEC) [13]. MAGEC allows a user to specify the melt composition, pressure, temperature, and starting fO2 and calculates the proportion of volatile species that would exsolve from the melt, and the fO2 of the remaining melt. This study uses the program MAGEC to evaluate the effect of volatile degassing on the redox evolution of shergottites.

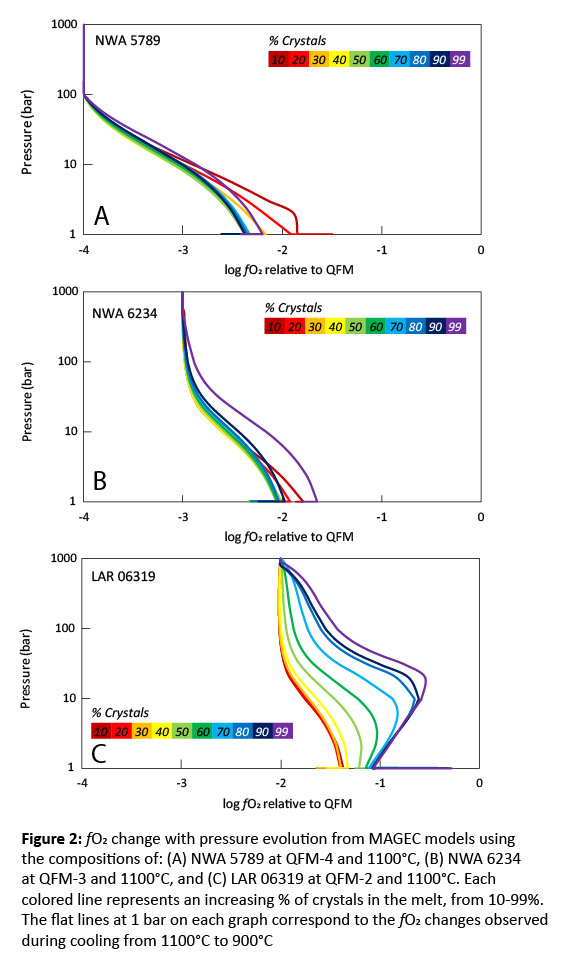

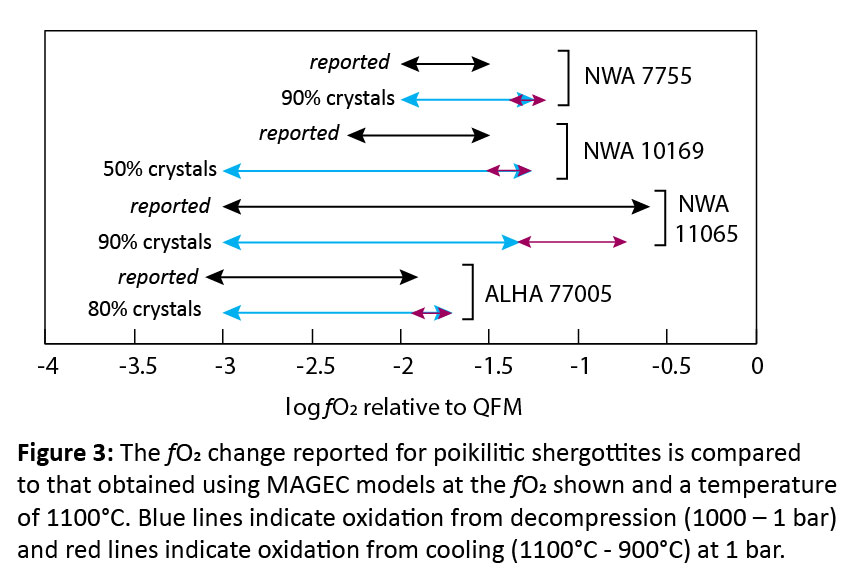

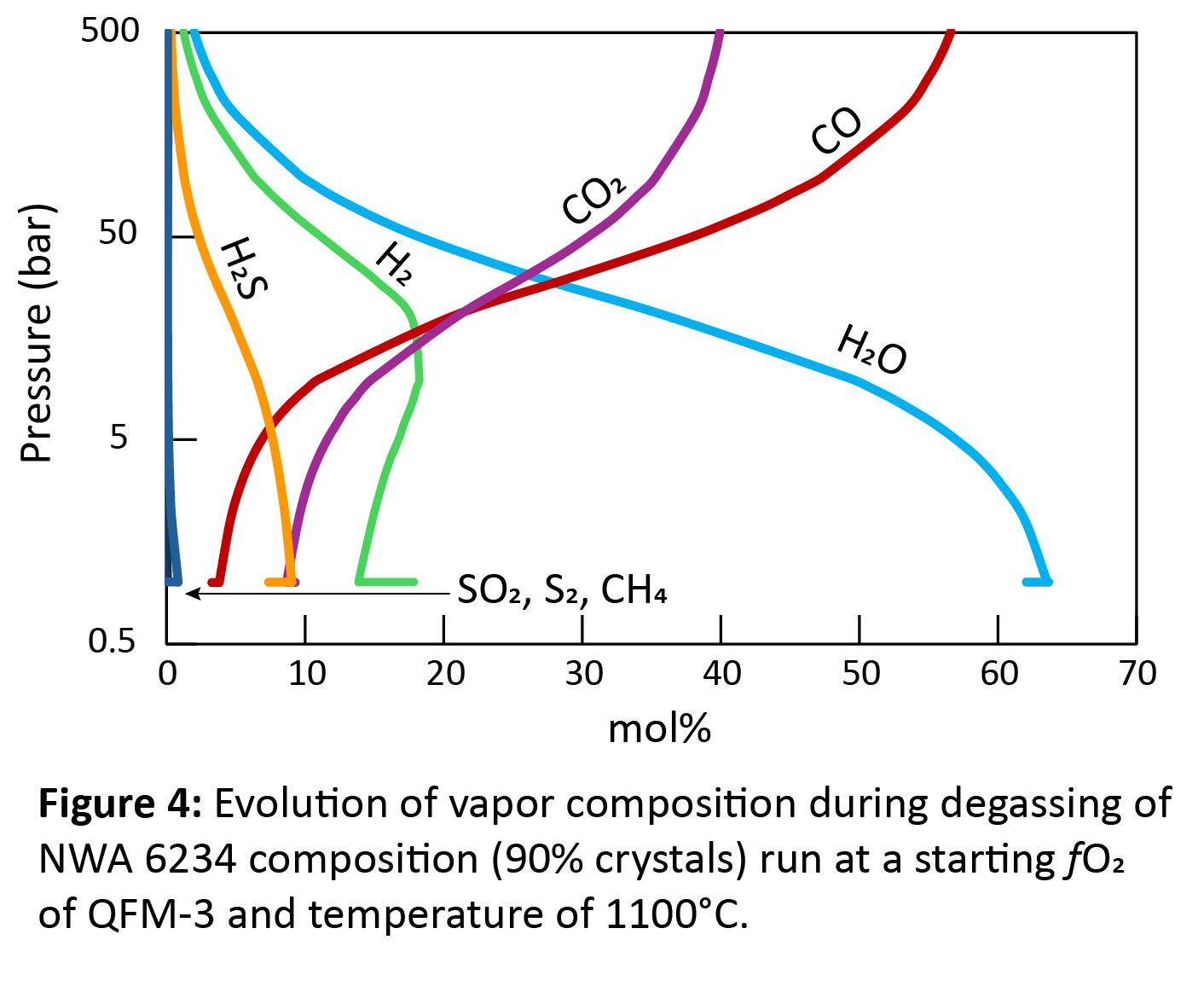

Methods: Various shergottite compositions were tested to capture the diversity within the group. The bulk compositions of olivine-phyric shergottites Northwest Africa (NWA) 5789 [14], NWA 6234 [15], and Larkman Nunatak (LAR) 06319 [16] were used, as these samples represent a mantle melt or closely approximate one, and thus, serve as representations of the martian interior. Additionally, the parental melt compositions of poikilitic shergottites NWA 7755, NWA 10169, NWA 11065, and Allan Hills (ALHA) 77005, estimated from their melt inclusions [6, 17], were used. Poikilitic shergottites were included in this study as they display some of the largest fO2 variations. To evaluate how changing melt composition can affect volatile degassing, all compositions were crystallized at 1 kbar at an fO2 of QFM-4, QFM-3, or QFM-2, using rhyolite-MELTS [18, 19]. The melt composition was recorded for every 10% of crystals formed, from 10%-99% crystals. Degassing models were run for every 10% increase in crystals/decrease in melt, with degassing from decompression occurring from 1000-1 bar at a temperature of 1100°C, 1050°C, 1000°C, or 950°C, and degassing from cooling occurring at 1 bar from the initial temperature down to 900°C. These models were run at an fO2 of QFM-4, QFM-3, or QFM-2, with 0.3 wt.% H2O, 0.08 wt.% CO2, and 0.5 wt.% S added. The volatile abundances used in this study are based on H, C, and S abundances estimated for the martian mantle and crust [7, 11, 20-24].

Results and Discussion: All models displayed oxidation through degassing from decompression (Figs. 2-3). However, the extent of oxidation depends on the composition of the melt and the initial fO2 of the melt before any degassing. While degassing from decompression consistently increased fO2, degassing during cooling generally decreased fO2, unless the melt was highly evolved (90-99% crystals)(Figs. 2-3). The composition of the vapor as the sample degassed during decompression was similar for all model runs. Initially, the vapor consisted of C-species (Fig. 4), which did not lead to significant changes in fO2 (Fig. 1); however, at pressures <100 bar, H-species become dominant, which is when the largest oxidative increases occur. For NWA 5789, the maximum oxidative increase (Δ+1.5) occurred when the melt had only crystallized 10-20%. Generally, however, the runs that showed the largest oxidative increases were those where the melt had crystallized 90-99% (Figs. 2-4). The largest increase in fO2 occurred in models run at QFM-4, with a Δ+1.5-2.75 log unit change seen. The smallest redox change occurred in models run at QFM-2, with a Δ+0.5-1 log unit change. This may explain why depleted and intermediate shergottites (Fig. 1) show the largest fO2 changes – they have magmatic fO2s of QFM-3 to QFM-4. The oxidative changes reported in the poikilitic shergottites studied could be replicated with the degassing models (Fig. 2). However, samples that had the greatest increase in fO2 required extensive crystallization (90-99%) to have occurred before degassing. This work suggests that the large fO2 changes seen in shergottites do not require martian magmas to be particularly hydrous to degas or require extensive auto-oxidation to occur. Additional models attempting to replicate the redox changes of other poikilitic, olivine-phyric, and basaltic/gabbroic shergottites are ongoing.

References: [1] Herd C.D.K., and Benaroya S. (submitted). [2] Castle N. and Herd C.D.K. 2017. MaPS 52, 125–146. [3] Peslier A.H. et al. 2010. GCA 74, 4543–4576. [4] Rahib R.R. et al. 2019. GCA 266, 463–496. [5] Shearer C.K. et al. 2013. GCA 120, 17–38. [6] Combs, L.M. et al 2019. GCA 266, 435–462. [7] Ardia P. et al. 2013. GCA 114, 52–71. [8] Armstrong L.S. et al. 2015. GCA 171, 283–302. [9] Ding, S. et al. 2014. GCA 131, 227–246. [10] Iacono-Marziano G. et al. 2012. GCA 97, 1–23. [11] Li Y. et al. 2017. JGR: Planets 122, 1300–1320. [12] Stanley B.D. et al. 2014. GCA 129, 54–76. [13] Sun C. and Lee C-T. 2022. GCA 338, 302–321. [14] Gross J. et al. 2011. MaPS 46, 116–133. [15] Filiberto J. et al. 2012. MaPS 47, 1256–1273. [16] Basu Sarbadhikari A. et al. 2009. GCA 73, 2190–2214. [17] O’Neal E.W. et al. 2024. GCA 373, 122–135. [18] Ghiorso M.S. and Gualda G.A.R. 2015. Cont. Min. & Petro. 169, 53. [19] Gualda, G.A.R. et al. 2012. J. of Petro. 53, 875–890. [20] Gaillard F. et al. 2013. Space Sci. Rev. 174, 251–300. [21] McCubbin F.M. et al. 2012. Geology 40, 683–686. [22] Paquet M. et al. 2021. GCA 293, 379–398. [23] Righter K. et al. 2009. EPSL 288, 235–243. [24] Stanley B.D. et al. 2011. GCA 75, 5987–6003.

How to cite: Benaroya Fucile, S. and Herd, C. D. K.: Degassing as the cause of the large redox variations seen in shergottites, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-873, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-873, 2025.