EPSC Abstracts

Vol. 18, EPSC-DPS2025-893, 2025, updated on 09 Jul 2025

https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-893

EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025

© Author(s) 2025. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Understanding the Long-term Rotational Evolution of Asteroids with Gaia

- 1University of Tokyo, Department of Earth and Planetary Science, Tokyo, Japan (wenhan.zhou@oca.eu)

- 2Laboratoire Lagrange, Observatoire de la Côte d'Azur, Université Côte d'Azur, France

- 3Department of Earth and Planetary Science, School of Science, the University of Tokyo, Japan

- 4Department of Physics, University of Hong Kong, China

- 5Center for Computational Astrophysics, Flatiron Institute, USA

- 6Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University, Czech

The rotational dynamics of asteroids are primarily governed by two mechanisms: collisions and the Yarkovsky–O'Keefe–Radzievskii–Paddack (YORP) effect. The YORP effect is a radiative torque resulting from the anisotropic emission of thermal radiation from irregularly shaped asteroids. These two processes dominate different rotational regimes. Because the strength of the YORP effect scales approximately as ~1/R2 (where R is the asteroid's radius), it is significantly more effective for smaller asteroids—typically those less than 50 km in diameter. In contrast, collisions are the dominant driver of rotational evolution for larger asteroids. Additionally, collisions play a crucial role in the spin evolution of very slowly rotating asteroids, whose low angular momentum makes them especially susceptible to even minor impacts.

For the past 40 years, astronomers have been puzzled by three major unexplained phenomena in asteroid rotation:

- Excess of slow rotators – A significant overabundance of asteroids with extremely slow rotation periods, first discovered in the 1980s (e.g. Pravec & Harris 2000 and references therein).

- Distribution of tumbling asteroids – A subset of asteroids that do not rotate about their principal axis (Harris 1994), yet their size-dependent distribution in the slow rotation regime follows a power law.

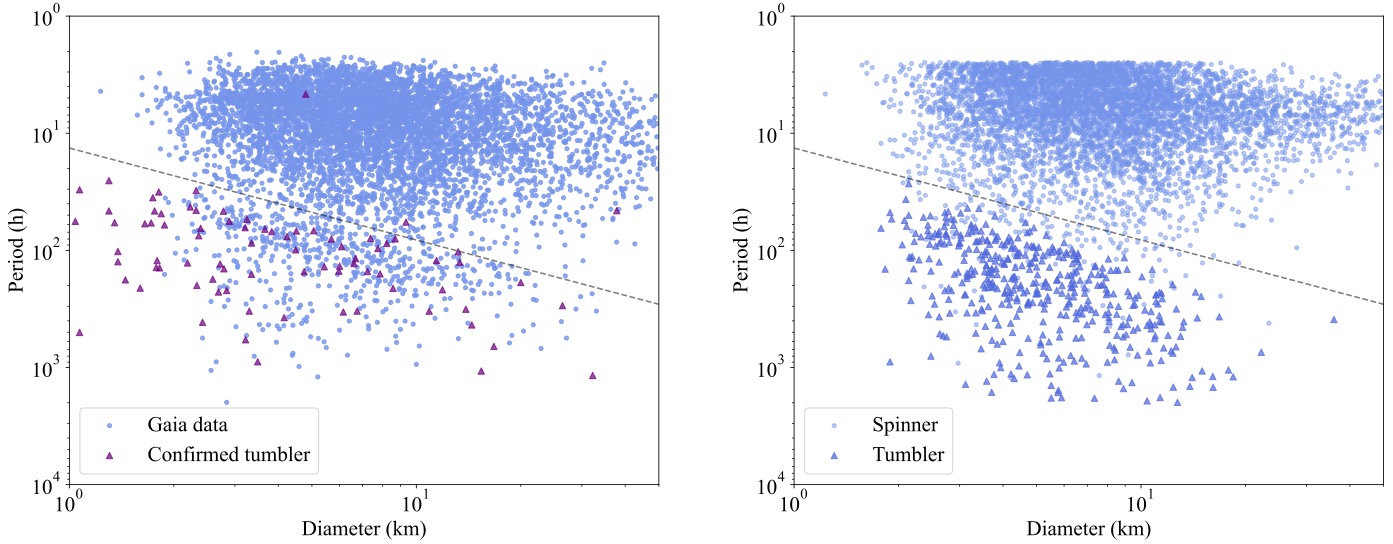

Recently discovered in Gaia data (Durech & Hanus 2023), the spin-size distribution of asteroids exhibits a gap, creating a previously unknown discontinuity in the population, as Fig. 1 shows.

Fig. 1. Period–diameter distribution: comparison of Gaia observations and simulations. Left: Observational data from Gaia (Durech & Hanus, 2023) showing the period–diameter distribution for asteroids, where the tumblers are identified using data from Asteroid Lightcurve Data Base (LCDB) (Warner, 2009). Right: Results from numerical simulations of the period–diameter distribution. The grey lines represent a fitted line that identifies the gap in the distribution.

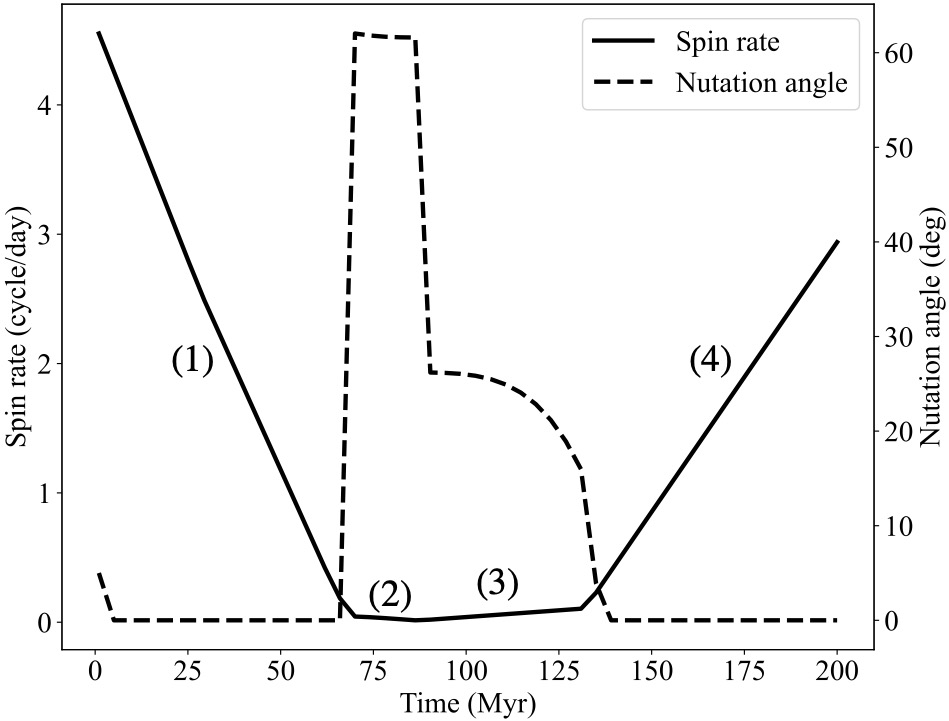

In our latest study (Zhou et al, 2025), we developed a new asteroid rotational evolution model that includes the collisions, YORP and non-principal axis rotation state (tumbling), successfully resolving all three of these long-standing mysteries. We show that most of slow rotators should be tumbling and their overabundance is caused by their slow evolution under the weakened YORP effect. These tumblers are trapped in the slow regions as collisions keep triggering a new onset of tumbling motion. A typical rotational evolution is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig.2. Rotational evolution of a synthetic asteroid over 200 Myr. The spin rate and nutation angle are denoted by the solid and dashed lines, respectively. This asteroid follows such a typical sequence: (1) it spins down, under the YORP effect, until it goes through a sub-catastrophic collision; (2) subsequently, the tumbling motion is triggered and it spins down at a slower rate than before due to a weak YORP effect until a new tumbling state is triggered; (3) then it starts to spin up at a slow rate until the tumbling is damped; (4) it spins up at a normal YORP acceleration until getting disrupted. It can be seen that the time fraction of lifetime in the slow region for asteroids is relatively high compared to that in the faster region, resulting in a larger number density of asteroid population in the slow region.

The gap is the boundary between pure spinner and tumblers (Fig. 3) and its location is regulated by the balance of collisions excitation and friction damping. We also found the location of the gaps is different for S-type asteroids and C-type asteroids. This could imply that the C-type asteroids dissipate energies faster than the S-type asteroids due to the difference of porosity and material properties.

Fig. 3. Bimodal period distribution for simulated asteroids between 3 km and 4 km as an example showing the location of the gap. The group of fast rotators is dominated by pure spinners while the group of slow rotators is dominated by tumblers. A distinct gap clearly separates the two groups.

References

Ďurech, J., & Hanuš, J. (2023). Reconstruction of asteroid spin states from Gaia DR3 photometry. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 675, A24.

Harris, A. W. (1994). Tumbling asteroids. Icarus, 107(1), 209-211.

Pravec, P., & Harris, A. W. (2000). Fast and slow rotation of asteroids. Icarus, 148(1), 12-20.

Rubincam, D. P. (2000). Radiative spin-up and spin-down of small asteroids. Icarus, 148(1), 2-11.

Warner, B. D., Harris, A. W., & Pravec, P. (2009). The asteroid lightcurve database. Icarus, 202(1), 134-146.

Zhou, W. H., Michel, P., Delbo, M., Wang, W., Wang, B. Y., Ďurech, J., & Hanuš, J. (2025). Confined tumbling state as the origin of the excess of slowly rotating asteroids. Nature Astronomy, 1-8.

How to cite: Zhou, W.-H., Michel, P., Delbo, M., Wang, W., Wang, B. Y., Durech, J., and Hanuš, J.: Understanding the Long-term Rotational Evolution of Asteroids with Gaia, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-893, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-893, 2025.