- University of Edinburgh, Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics and Astronomy, Edinburgh, United Kingdom of Great Britain – England, Scotland, Wales (brian.murphy@ed.ac.uk)

Abstract

Small bodies of the Solar System can display an array of active behaviors and extended morphologies, such as the sublimation-induced production of transient atmospheres called comae, and the rocky ejecta clouds instigated by impacts or geomorphological surface alterations. These comae and ejecta clouds are visible from Earth, and can therefore provide crucial information about the conditions and composition of the parent body, whether it be an asteroid or comet. Through studying these structures with spatially-resolved integral field unit (IFU) spectroscopy, we can directly disentangle and compare the synchronous gas and dust components, and better understand the activity mechanisms behind their formation and how to more robustly link comae and ejecta clouds to the parent body (Opitom et al, 2019.). Here, we present the culmination of dissertation work on around 900 IFU observations from the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE) instrument at the Very Large Telescope (VLT), highlighting novel findings on the post-Double Asteroid Redirect Test (DART) Didymos-Dimorphos ejecta cloud and the chemomorphological coma evolution of 31 comets, including previous mission targets 9P/Tempel, 19P/Borrelly, 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, 73P/Schwassmann–Wachmann, 81P/Wild, and 103P/Hartley (Murphy et al., 2023; Murphy et al., 2025; Murphy et al., in prep).

Observations

We observed 31 comets and 1 active asteroid with the MUSE IFU spectrograph, from 2016 to 2024, across ESO programmes: 60.A-9800(T), 0102.C-0395(A), 0102.C-0395(B), 105.2086.001, 105.2086.002, 106.216F.001, 108.223B.001, 109.22ZS.001, 110.23TK.001, 111.24KA.001, 112.25H1.001, 113.269X.001, and 114.28H0.001. MUSE collects spatio-spectral datacubes, which consist of two spatial dimensions and one spectral dimension (x,y,λ). Across these observations, we primarily utilised MUSE in wide field mode (WFM, 1'x1',0.2"/pix), however, employed narrow field mode (NFM, 8"x8", 0.025"/pix) with adaptive optics (AO) for the DART observations. MUSE covers the 4800 to 9300A wavelength range with an average resolving power of 3000 (Bacon et al. 2010). Generally, we exposed MUSE for 600 seconds, used non-sidereal tracking, and rotated by 90° between observations. Standard stars were observed for flux calibration, followed by an O-S-O-O-S-O (O-object, S-sky) pattern for science exposures. The sky observations were positioned around 10 arcminutes from the system to ensure no diffuse contributions from comae or ejecta clouds. We also conducted offset observations for Didymos-Dimorphos, in order to better capture the rapidly evolving tail. We reduced the dataset using the ESO MUSE Pipeline (Wielbacher et al. 2020), ESO Molecfit Package (Smette et al. 2015), and custom continuum- and emission-isolation scripts.

Results

This work demonstrates the efficacy of integral field spectroscopy in resolving the spatial and spectral characteristics of small body activity and extended morphologies across the Solar System. Regarding the Didymos–Dimorphos system, we tracked the post-impact evolution of the ejecta over 11 nights following the DART collision and identified multiple morphological components; the ejecta cone, near-asteroid spirals, late-evolution wings, and dual debris tails. Complimenting other works (Li et al., 2023, Lin et al. 2023, Opitom et al., 2023) the ejecta cone opened at an angle of ~127±1°, the inner spirals corresponded to the binary gravitational dynamics, the bases of the two late-stage dust wings were comprised of grain sizes ~0.05–0.2 mm, and the unexpected secondary tail was detected on October 3 2022, earlier than any other study. We find that the secondary tail widths, position angles, and relative flux slopes indicate a similar origin to the primary tail, i.e. creation via surface impact(s). We tracked distinct clumps of material in the ejecta cloud, and extracted spectral slope measurements that showed redder colors associated with later clumps of larger, slower grains (~0.09m s-1), indicating that the ejecta cloud clumps are structurally or compositionally distinct from the rest of the ejecta cloud and are not line-of-sight apparitions.

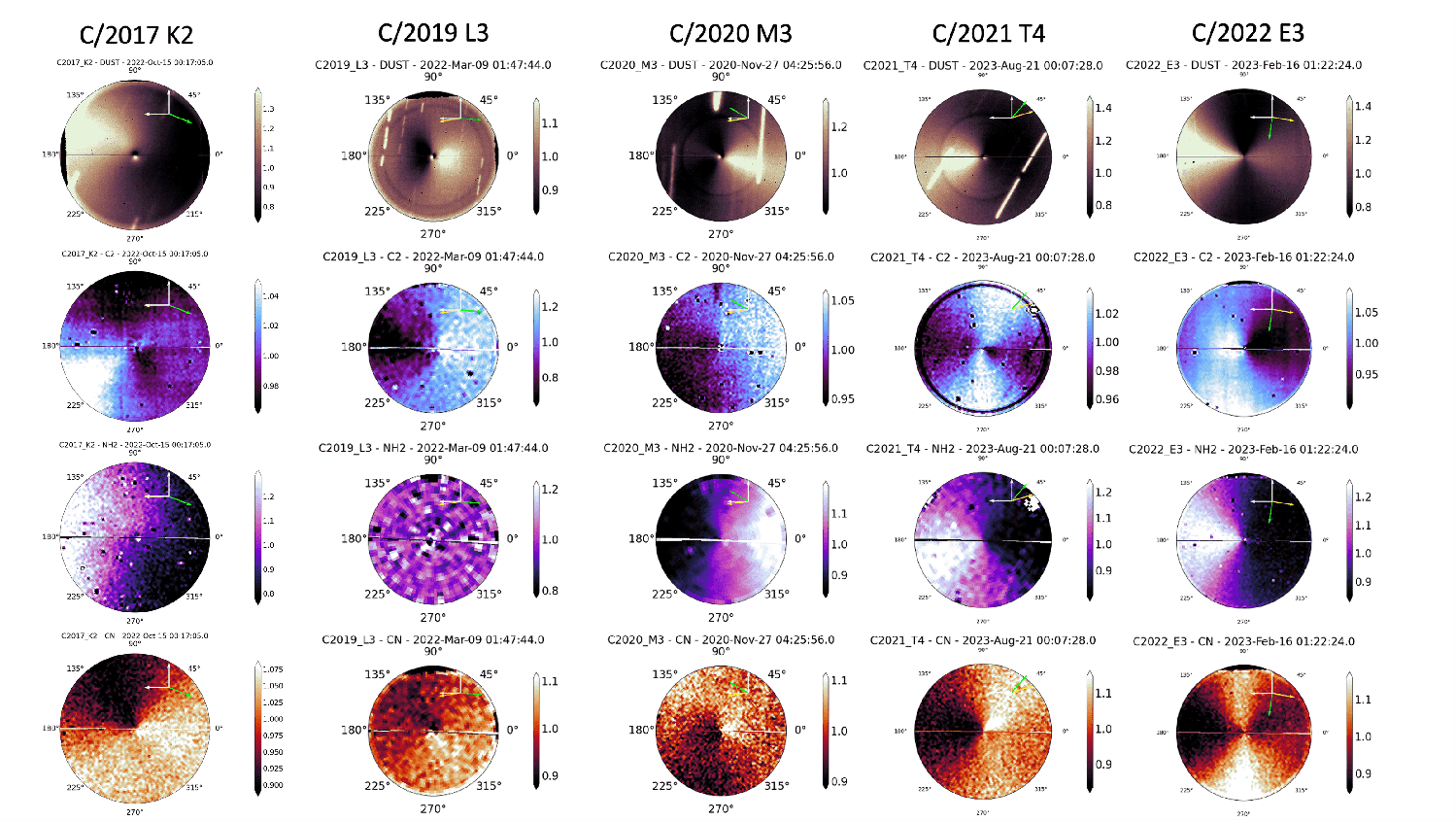

Fig. 1:Molecular and dust maps of five long period comets. All maps have been enhanced by division by azimuthal median, thus removing the diffuse component of the coma. The top row is the dust, the second row is C2, the third row is NH2, the fourth row is CN. North is up, and left is East. The yellow arrow represents the sunward position angle, and the green arrow is the velocity vector.

Regarding the comets observed with MUSE, we began with comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (hereafter 67P) due to the rich in-situ findings and context of the ESA/Rosetta mission (Koschny et al. 2007; Schulz 2012; Taylor et al. 2017). We analysed 11 MUSE epochs from the 2021 perihelion passage of 67P and extracted concurrent coma maps of [OI], C2, NH2, CN, and dust. We found that CN and NH2 emissions were strongly correlated with known dust fans, and retrieved NH2 effective scale lengths up to 1.9x those fitted elsewhere in the coma—supporting the presence of extended sources. Furthermore, dust spectral slopes ranged from 8–18%/1000A , consistent with Rosetta findings, while [OI] green-to-red line ratios (G/R) confirmed H2O as the dominant driver of coma production at the heliocentric distances we probed (G/R ≅ 0.1, 1.2-1.7 au). Looking forward, we are applying the same calibrated methodology to the remaining 30 comets, which span 0.6-19 au and a diverse range of taxonomic and dynamical classes and families. We have isolated similar gas and dust species, and computed spectral slopes, across this sample of comets, resulting in 585 comae maps. Throughout these maps, we find that long period comets exhibit more complex morphologies, with a higher rate of heterogeneous coma structure (~50% of maps), as seen in Figure 1. We do find complex morphologies in the short period comets, however, at a much lower rate of detection and largely homogeneous across species. Further analyses, modeling, and reduction are underway to better understand these trends.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the following collaborators and colleagues for their support or data in these works, and in the dissertation, thus far: Colin Snodgrass, Matthew Knight, Rosita Kokotanekova, Bin Yang, Cyrielle Opitom, Sophie Deam, Lea Ferellec, Jian-Yang Li, Nancy L. Chabot, Andrew S. Rivkin, Simon F. Green, Michele Bannister, Aurélie Guilbert-Lepoutre, Paloma Guetzoyan, Vincent Okoth, Daniel Gardener, and Julia de León. Furthermore, the author highlights funding support from the United Kingdom Science Technology and Facilities Council, Royal Astronomical Society, and International Space Science Institute.

How to cite: Murphy, B.: Toward Understanding the Coma and Ejecta of Comets and Active Asteroids with Integral Field Spectroscopy, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-900, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-900, 2025.