Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

MITM9

Session assets

INTRODUCTION

After the failure of the landing of Rashid-1 on the Moon, in April 2023, the MBRSC (Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre) decided to set up a new mission with the same rover design. It is expected that Rashid-2 will land in the mid-latitudes of the Moon in 2026. This paper focuses on the calibration of its optical cameras.

OPTICAL CAMERAS DESCRIPTION

The Rashid-2 rover carries 3 multispectral visible (RGB) cameras, as shown Figure 1. Their design is identical to that of Rashid-1, see [1]-[2]-[3] for more details. Basically, CAM-1 and CAM-2 are wide-angle navigation cameras, with a full diagonal angle of 115°, and CAM-M is a microscopic camera, with a spatial resolution better than 30µm.

DETECTOR CHARACTERIZATION

We first characterized the radiometric response of the CMOS detectors, in terms of gain, offset, dark current and readout noise, by measuring the average levels and the spatial non-uniformity maps. The dynamics of the detectors are encoded in 10 bits and the measured gains are:

- CAM-1: 0.346 DN/e-

- CAM-2: 0.173 DN/e-

- CAM-M: 0.147 DN/e-

The average levels are given with respect to the temperature in Figure 2 and the standard deviation of the non-uniformity maps are always between 4% and 5% at ambient temperature (except for CAM-M offset: 7%). The dark current is approximated by an Arrhenius law adapted for the high levels: dark=exp(62.5-1.5/kT). Actually, it is only properly measured for CAM-M because the camera was not yet integrated, so the temperature could be measured directly on the detector. However, we can relate an internal uncalibrated temperature register from the detector to the measured dark current. This relation will be used during the mission.

INTEGRATED CAMERAS CHARACTERIZATION

INTEGRATED CAMERAS CHARACTERIZATION

This section only describes CAM-1 and CAM-2, as they are integrated at CNES. CAM-M is integrated by Kampf Telescope Optics in Munich[3]. These characterizations include the effects of the optical components.

Radiometry

Radiometric calibration consists of three distinct measurements:

- The spatial non-uniformity of the response, both at low and high frequencies,

- The spectral shape of the response (colorimetric response),

- The absolute radiometric response to a typical scene.

The non-uniformity is evaluated by illuminating the camera with a uniform illuminant generated by an integrating sphere. The integration time is chosen in order to obtain the higher dynamics in the images without saturation. A burst of images is acquired to reduce the noise effects and derive the flat field (Figure 3-left).

A median filter is then applied to extract only the low frequency component, i.e. the vignetting effect. By dividing it to the measured flat, we can also estimate the Pixel Response Non Uniformities (Figure 3-right) and detect defective and “noisy” pixels that are far from the standard response. This vignetting/PRNU separation will be done on the fly during the mission by the CASPIP[4] operational library.

Knowledge of the instrument’s colorimetry is necessary for proper interpretation of the spectral distribution of the observed scene, which is required for geological analysis[1]. It is calibrated using color patches of known reflectance, in a dedicated chamber that reproduces a spectrum similar to the sunlight reflected from the lunar surface, in order to mimic the lunar illuminant. The result is a 3x3 matrix that is used to convert camera’s readings into human-perceivable colors.

The absolute response is measured in the same chamber with a spectralon. The Digital Numbers are averaged around the center of the image, where the effect of vignetting is negligible. Knowing the mean offset and the mean dark current from the detector characterization, we can calculate the absolute radiometric coefficient that relates the measurement (in DN) to the flux (in W/m²/sr/µm), see Figure 4 for the resulting values.

Resolution

The cameras resolution is measured using the slanted-edge method[5], which is extended over the field of view with a checkerboard pattern (Figure 5-a). The slanted-edge method directly calculates the MTF curves in the vertical and horizontal directions for each transition, but it is affected by noise at high frequencies. Moreover, it is necessary to demosaic the Bayer pattern before computing the MTF, so as not to be limited to half the sampling frequency, and thus the MTF is also affected by the mosaicing/demosaicing operations[6]. However, it results in a representative MTF as obtained on the final product. It is approximated and extrapolated by an exponential law (Figure 5-b).

Geometry

Geometry

These wide-angle cameras introduce a large distortion to the images. It is approximated by a specially tuned polynomial model[1]. The parameters of the model are calculated by fitting it to images of the checkerboard pattern captured at different positions and orientations (Figure 6-up). The transitions on the checkerboard are detected using a Canny filter and the MTF response to account for the smoothing of the edges. The resulting polynomial is given in Figure 6-bottom.

CONCLUSION

The Rashid-2 cameras have been calibrated on-ground and are now integrated on the rover. Launch and landing operations, as well as thermal variations on the Moon, may affect some parameters, so additional calibrations will be performed onboard during the mission, with more constraints on their realization.

REFERENCES

[1] N. Théret, E. Cucchetti, E. Robert et al., Enhanced Image Processing for the CASPEX Cameras Onboard the Rashid-1 Rover. Space Sci Rev 220, 60 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-024-01091-0

[2] Z. Ioannou, S. Amilineni, S.G. Els et al., Onboard and Ground Processing of the Wide-Field Cameras of the Rashid-1 Rover of the Emirates Lunar Mission. Space Sci Rev 221, 8 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-024-01127-5

[3] S.G. Els, N. Ageorges, M. Bogosavljevic et al., The Microscope Camera CAM-M on-Board the Rashid-1 Lunar Rover. Space Sci Rev 220, 81 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-024-01117-7

[4] N. Théret, Q. Douaglin et al., CASPEX Image Processing: a tool for space exploration, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-15

[5] M. Estribeau et P. Magnan, Fast MTF measurement of CMOS imagers using ISO 12233 slanted-edge methodology, SPIE Optical System Design 2003

[6] N. Théret, A. Courtois, Q. Douaglin et S. Lucas, Mesure de FTM optique sur caméras intégrées avec motifs Bayer, in preparation

How to cite: Théret, N., Guénin, M., Bonassi, T., Douaglin, Q., Virmontois, C., Lalucaa, V., and Els, S.: Preparing Rashid-2 Lunar Mission: calibration of the optical cameras, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-27, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-27, 2025.

Introduction

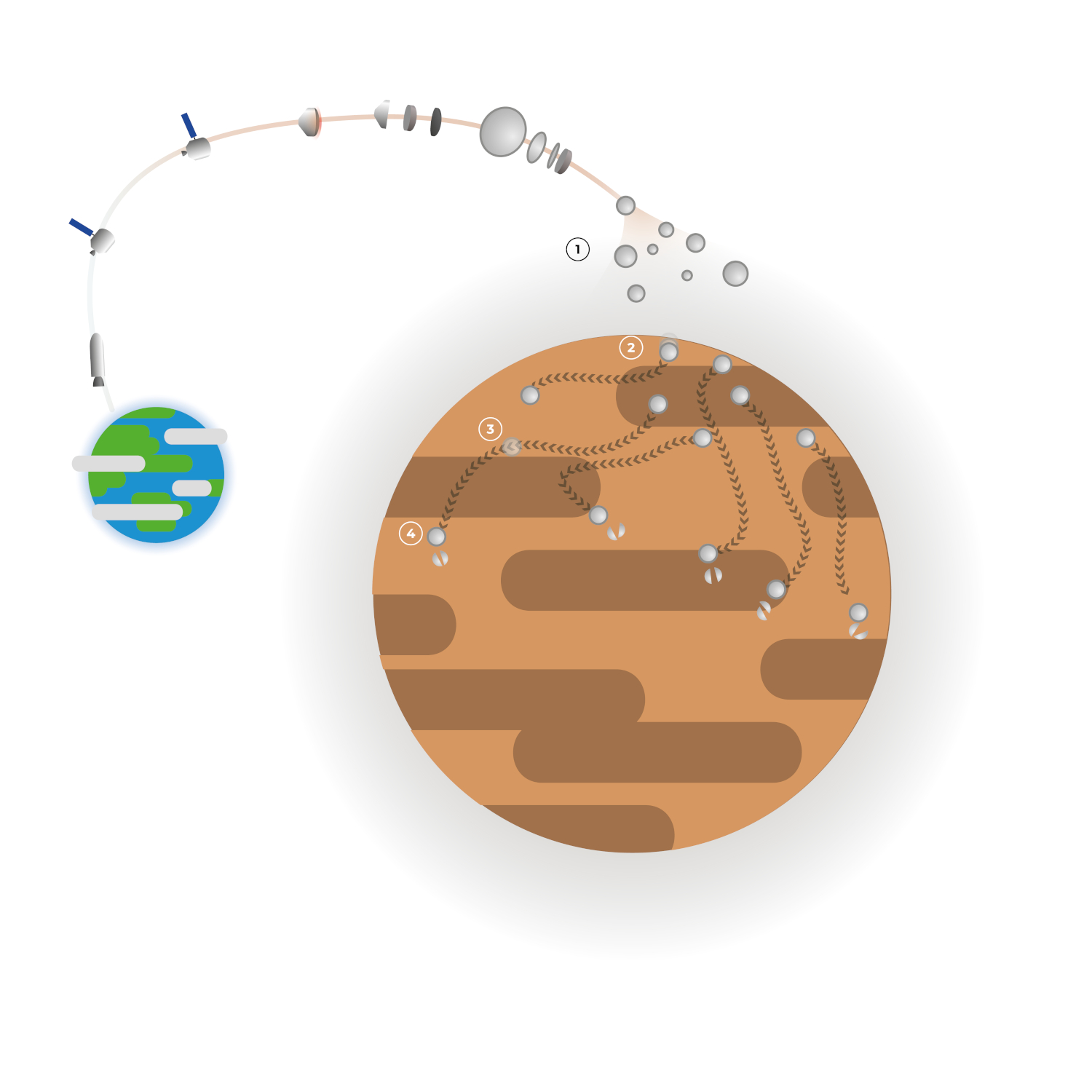

The main goal of the ESA ExoMars Rosalind Franklin (EMRF) rover mission is to search for past and present life on Mars [1]. Enfys is a new near-infrared spectrometer, added to the mission in 2023, currently under development, before Flight Model (FM) delivery in 2026 and launch in 2028. The EMRF rover will land in Oxia Planum in 2030, and Enfys will form part of the suite of remote sensing instruments used for exploration and target selection. Given the importance of near-infrared spectroscopy in selection of the landing site [2-4], Enfys will play a major role not only in mission operations, but also in helping to link orbital and in situ observations and interpretations, which has been shown to be vital in other rover missions [e.g. 5].

Instrument Design

The function of Enfys is based around utilizing two near-infrared Linear Variable Filters (LVTs), each with a dedicated detector. An uncooled InGaAs photodiode is paired with a LVF covering the wavelength range 0.9 – 1.7 mm. A cooled InAs photodiode is paired with a LVF covering the wavelength range 1.6 – 3.1 mm. Both LVFs are translated simultaneously on a mechanical stage. There are two main parts to the Enfys instrument. (1) The Optical Box (OB) sits on top of the EMRF mast, co-aligned with and directly underneath the High Resolution Camera (HRC) element of the Panoramic Camera (PanCam) instrument [6]. The OB contains the optics, detectors, mechanism, and associated electronics. (2) The Electronics Box (EB) is situated inside the EMRF ‘bathtub’, and provides power and control for the OB, and the data interface with EMRF. An umbilical cable running up the mast of EMRF connects the OB and EB.

Instrument Synergy

Embedded within the design is an overlap in wavelength range with PanCam, allowing synergy between multispectral imaging and point spectroscopy. Together these instruments provide contextual remote sensing information, prior to selection of drill sites. Enfys data will be complementary to the other near-infrared spectrometers on EMRF, namely Ma-MISS [7], which will collect data from within the drill hole, and MicrOmega [8], which will analyze the drill core once collected, prepared and delivered into the analytical suite inside EMRF.

Scientific Preparations

We are carrying out concurrent and complementary projects to ensure not only rigorous calibration, but also to maximize the scientific return from Enfys. The predicted spectral performance of Enfys suggests that identification of all mineral types identified from orbit to date should be feasible. Part of the preparation work includes devising operating procedures that will help identification of more subtle absorption features (e.g. vermiculite doublets), in order to discriminate between phyllosilicate mineral types for example. Future efforts will also derive a comprehensive component-level mathematical model of the spectro-radiometric response of Enfys, which will be validated and implemented in software.

Acknowledgements: We are grateful for support from the UK Space Agency (grants ST/Z510427/1, ST/Z510415/1, ST/Y005996/1, ST/Y005287/1).

References: [1] Vago, J.L., et al. (2017) Astrobiol. 17, 471-510. [2] Quantin-Nataf, C. et al. (2021) Astrobiol. 21, 345-366. [3] Mandon, L., et al. (2021) Astrobiol. 21, 464-480. [4] Brossier, J. et al. (2022) Icarus 115114. [5] Fraeman, A.A. et al. (2020) JGR 125, e2019JE006294. [6] Coates, A.J. et al. (2017) Astrobiol. 17, 511-541. [7] De Sanctis, M.C. et al. (2017) Astrobiol. 17, 612-620. [8] Bibring, J.-P. et al. (2017) Astrobiol. 17, 621-626. [9] Seelos, K.D. et al. (2019) LPSC 50, #2745. [10] Million, C.C. et al. (2022) LPSC 53, #2533.

How to cite: Grindrod, P. M., Cousins, C., Stabbins, R., Hagan-Fellowes, S., Nielson, G., Marsh, H., Langston, J., and Gunn, M.: Enfys: A Near-Infrared Spectrometer for the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-154, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-154, 2025.

Introduction:

Understanding the properties of planetary regolith is essential to predict the response of a surface to interactions and correctly interpret the outcome of in-situ operations. In preparation for the interpretation of data from small body missions with surface interaction, we investigate models relating the dynamics of an impact into granular media and the mechanical properties of the surface material. The objective is to constrain frictional properties of regolith using data acquired during landing.

Methods:

Landing on small bodies can be modelled as low-velocity collisions into a granular material in low-gravity conditions. We use experimental data to assess the agreement between empirical scalings from collisional models and frictional properties. Our data are from past impact experiments [3,4] conducted in terrestrial (1g) and low-gravity conditions using a drop tower [5]. The experiments consist of releasing an instrumented spherical projectile from a controlled height into a granular material. From the acceleration profile, the velocity and position are derived by integration. Here, we focus on specific datasets obtained for glass beads and quartz sand of average grain sizes 1.5 mm and 1.8 mm, respectively. The experimental range of impact velocities is 0.2 – 1.2 m/s in 1g and 0.01-0.4 m/s in low-gravity. The average gravity level in the low-gravity experiments is 1.8 m/s² for the glass beads and 0.8 m/s² for the sand.

Results:

We consider the time series for acceleration, velocity, and position of the projectile during impact for various impact velocities. To describe the impact dynamics, the Poncelet collisional model is frequently used, including a drag force composed of two contributions: quasi-static friction and hydrodynamic drag. In Katsuragi et al. [1] the quasi-static term is linear in depth (z), and in the framework of Sunday et al. [2], this component is modified to highlight a regime transition after a certain depth z1, at which the quasi-static friction saturates.

Here we consider a hydrodynamic drag coefficient h(z), and a depth-dependent quasi-static friction force f(z), giving the following equation of motion:

ma = mg – Fd, with Fd = h(z)v² + f(z) (1)

We plot the total drag force Fd in Fig. 1 for the glass beads and the sand as a function of the velocity squared at different depths in the material. The slope of each linear fit is the hydrodynamic coefficient h(z), and the intercept is the quasi-static friction f(z). We represent the estimated quasi-static friction force against depth in Fig. 2.

In 1g, the quasi-static friction force increases linearly until the transition depth where it becomes roughly constant, consistent with [2]. Using this model, the transition depth z1 and the saturated friction force f0 can be determined (Fig. 2). As expected, the sand is more frictional than glass beads. The derived parameters (f0, z1) are also consistent with previous estimates using a different method [4].

In low-gravity, the quasi-static friction is considerably lower and approximately constant with depth, in agreement with previous studies showing that the quasi-static regime is significantly reduced in low-gravity [2-4]. The consequence is that we cannot identify a clear transition depth, nor fit the quasi-static force parameters.

Different empirical scalings from impact models have been proposed to relate the drag force coefficients to the angle of repose of the material. We show in Eq. 2 the scaling from [6] for the coefficient of friction (µf) using the coefficient of the quasi-static term k, and in Eq. 3 the scaling from [2] using the equivalent f0/z1 term.

We find that the scaling of [6] (Eq. 2) overestimates µf. However, when using the model of [2] (Eq. 3) accounting for the regime transition, the 1g experimental results provide results consistent with measured values of µf. In low-g, the use of these scalings is no longer possible given the absence of the quasi-static friction regime. Therefore, to retrieve frictional properties in low-gravity, scalings based on the hydrodynamic component need to be used.

Conclusions and perspectives:

We quantify the drag force in low velocity impact experiments into granular material in both 1g and low-gravity conditions. Our results show that the quasi-static friction is considerably lower in low-gravity and approximately constant with depth, in agreement with previous studies [2-4]. We also show that the model of Sunday et al. [2], provides the most reliable estimates of the material frictional properties in 1g. However, the same approach cannot be applied in low-gravity due to the absence of the quasi-static friction term. This analysis will be expanded to additional datasets, in order to further examine the influence of friction, grain size, and gravity levels and we will also address the challenge of retrieving mechanical properties from a single impact event. Finally, new experimental data will be collected from the future variable-gravity tower at ISAE-SUPAERO [8] and will bring us means to further investigate the mechanics of regolith in low-gravity.

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge funding support from CNES (in the context of Hera and MMX rover/wheelcam), from the French ANR Tremplin-ERC ‘GRAVITE’, and from the European Research Council (ERC) GRAVITE project (Grant Agreement N°1087060).

References:

[1] Katsuragi, H., & Durian, D. J., Nat. Phys., 2007. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphys583

[2] Sunday, C. et al., A&A, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202142098

[3] Murdoch, N. et al., MNRAS, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stw3391

[4] Murdoch, N. et al., MNRAS, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stab624

[5] Sunday, C. et al., Rev. Sci. Inst., 2016. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4961575

[6] Katsuragi, H., & Durian, D. J., PRE, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.87.052208

[7] Kang, W. et al., Nat. Comm., 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03344-3

[8] Wilhelm, A. et al., EPSC-DPS, 1355, 2025.

How to cite: Bigot, J. and Murdoch, N.: Deriving frictional properties of regolith during small body landing, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-690, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-690, 2025.

The Automated Lander Planetary Analog Composition Analyzer (ALPACA) is a chemical and organic composition analyzer well suited for future landed missions to ocean worlds such as Enceladus, Europa, and Titan. ALPACA utilizes the Biosignature Preparation for Ocean Worlds (BioPOW) instrument for sample enrichment (concentrating the sample) and purification to enable detections in challenging ocean world environments [1]. The BioPOW system performs the following operations: 1) melt an icy sample; 2) purify amino acids, and other organics, from salts and inorganic compounds [2]; 3) concentrate and derivatize targeted amino acids for downstream GC analyses (Figure 1). The downstream GC analyses are accomplished with a micro-electromechanical system gas chromatograph (μ-GC) [3–5]. The ALPACA instrument is being developed under NASA’s Planetary Science and Technology Through Analog Research (PSTAR) program (NASA Grant 80NSSC25K7720).

The automated, on-chip BioPOW system receives an icy sample in a sample cup that was specifically designed to interface with the CADMES arm described in NASA’s ICEE-2 program. Sample cup testing demonstrated repeatability and reliability for melting icy samples with steady heating to 100 °C in ~350 seconds using embedded nichrome wire. Once melted, fluid is transferred to the cation exchange module (ion exchange chromatography column) that is referred to as the Wet Lab of the BioPOW system. For purification and concentration of amino acids, the following steps are performed: 1) Use 10 mM hydrochloric acid (HCl) to de-protonate the resin (cation exchange beads) and provide an overall negative charge; 2) acidified sample (4OH) elutes the amino acids from the resin for subsequent derivatization and analysis (Figure 2). The eluted amino acids are moved to the second portion of the BioPOW Wet Lab, the derivatization chamber. The eluted sample is dried (60 °C until powder) and derivatized with MTBSTFA (90 °C for 1 hour) using the custom-built derivatization chamber. The derivatization chamber has three ports, one for inserting the sample and MTBSTFA, another for carrier gas, and one output which is used for water-vapor exhaust during the drying stage and for delivering the derivatized amino acid vapor to the μ-GC. Metal microfluidic tubing connects the chamber to input sources and output for the high temperatures required during derivatization. Minco® heater elements wrapped around the chamber provide the heat source.

The μ-GC utilizes silicon chip-based technology for miniaturization and consists of three main parts: 1) preconcentrator; 2) separation column; and 3) detectors. The preconcentrator is made from deep-reactive ion etching (DRIE) of silicon wafers for μ-channel ports for carbon molecular sieve (bead) loading, sample loading (preconcentration), carrier gas and vacuum pump connection, and outlet connection to the μ-GC separation column (μ-column). The molecular sieve material is used for the trapping and preconcentration of analytes with different molecular sieves targeting different analyte sizes (shown as the number of carbons in the molecule in Figure 3). The preconcentrators can employ a single sieve or multiple-sieve configurations (4-sieve configuration in Figure 3). A vacuum pump is used to pull samples across the preconcentrator where target analytes are trapped and accumulate with increased sampling time. Once sampling is completed, the vacuum pump is turned off and μ-valves switch to allow the flow of carrier gas (He) through the preconcentrator and to the μ-column. The preconcentrator is resistively heated to desorb the trapped analytes for separation on the μ-column. The μ-column is made of square spiral channels from DRIE silicon wafers of dimensions 3 x 3 cm or 3 x 6 cm for 5- and 10-m effective column length, respectively. The square spiral channels are coated with a variety of liquid stationary phases to target different analyte selectivity within each μ-column. Finally, at the exit of the μ-column, the separated analytes pass through high sensitivity μ-detectors for detection. The μ-detectors employed are a micro-photoionization detector (μ-PID) sensitive to most organics and a micro-helium dielectric barrier discharge photoionization detector (μ-HD-PID) sensitive to fixed gases (minus helium and neon). The MEMS technology significantly decreases the size, weight, and power (SWaP) of the device thereby enabling multiple μ-GCs in a single enclosure, referred to as a μ-GC suite (Figure 4) [5].

In this presentation, we focus on ALPACA hardware development and the recent advances that have been made to impact future landed missions.

References

[1] K.A. Duval, et al., Biosignature preparation for ocean worlds ( BioPOW ) instrument prototype, (2023) 2023–2032. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspas.2023.1244682.

[2] T. Van Volkenburg, et al., Microfluidic Chromatography for Enhanced Amino Acid Detection at Ocean Worlds, Astrobiology. 22 (2022) 1116–1128. https://doi.org/10.1089/AST.2021.0182/SUPPL_FILE/SUPP_DATA.PDF.

[3] R.C. Blase, et al., Experimental Coupling of a MEMS Gas Chromatograph and a Mass Spectrometer for Organic Analysis in Space Environments, ACS Earth Sp. Chem. 4 (2020) 1718–1729. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsearthspacechem.0c00131.

[4] R.C. Blase, et al., MEMS GC Column Performance for Analyzing Organics and Biological Molecules for Future Landed Planetary Missions, Front. Astron. Sp. Sci. 9 (2022) 828103 (1–19). https://doi.org/10.3389/FSPAS.2022.828103.

[5] R. Blase, et al., Biosignature detection from amino acid enantiomers with portable GC systems, Adv. Devices Instrum. (2024) 11–23. https://doi.org/10.34133/adi.0049.

Figure 1. BioPOW a) sample processing scheme, consisting of the B) sample cup, 1cm scale bar, C) wet lab manifold with cation exchange cartridge, 4 cm scale bar and D) concentration and derivatization tank, 1 cm scale bar. E) Integrated operational workflow where sample loading (gray box) is assumed performed by an external system (from [1]).

Figure 2. BioPOW system overview that 1) melts ice sample, 2) purifies amino acids, and 3) dries amino acids to concentrate and derivatizes for downstream GC analysis. 2b) Overview of steps in the cation exchange process, modified from [2].

Figure 3. Diagram of preconcentrator, from ref [5], used in μ-GC for preconcentrating analytes prior to desorption onto the μ-column for separation of complex sample mixtures.

Figure 4. μ-GC suite layout using multiple preconcentrators, μ-GCs, and μ-detectors for analyte selectivity in each μ-GC and broad chemical coverage over the entire suite.

How to cite: Blase, R., Libardoni, M., Craft, K., Bradburne, C., and Fan, X.: Automated Lander Planetary Analog Composition Analyzer (ALPACA), EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-890, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-890, 2025.

Introduction: Quantifying and mapping the precise amount of water ice in the subsurface of the Moon has proven challenging using only remote sensing data. However, this knowledge is crucial for planning long-term exploration missions that rely on the utilization of potential water reserves. Higher-resolution data and ground truth can be obtained by in-situ measurements. Instruments on stationary landers, such as ESA’s upcoming PROSPECT instrument package [1], will analyze the vertical distribution of water up to 1 m depth. In addition, rover missions promise to be highly valuable assets for lunar exploration as their mobility allows them to analyze the lateral distribution of water ice around its landing site at much higher resolution than presently possible [2].

Studies have shown that water ice in the lunar regolith can be detected using electric permittivity sensors [3,4,5]. By measuring the temperature- and frequency-dependent electric permittivity in the extremely low-frequency band, the soil’s porosity and water ice content can be deduced. Permittivity sensors of varying complexity have been part of the Rosetta/Philae [6] and Cassini/Huygens payloads [7], and a drill-based sensor will be employed in the upcoming Intuitive Machine’s IM-4 mission as part of ESA’s PROSPECT instrument package.

Rover Permittivity Sensor: For an ESA contribution to an upcoming lunar rover mission by the MBRSC (UAE), we are currently investigating the feasibility of a rover-wheel-based permittivity sensor. A prototype of this Rover Permittivity Sensor (RPS) is currently being tested at the Technical University of Munich [8]. The sensor architecture is based on the PROSPECT P-Sensor design with added sensor capabilities and circuitry adaptations. Advantages of the instrument are its simplicity, operational robustness, and low mass, power, and data requirements.

The RPS design features four distinct elements: Two electrodes mounted on one of the rover wheels, one of which is equipped with a thermometer, a coaxial pancake slip ring to transfer the signal from the rotating wheel to the static rover body, a backend electronics board performing sensor signal conditioning, acquisition, and analog processing, and a thermopile sensor to measure the surface temperature in the close vicinity of the rover.

RPS utilizes two electrodes, which allows to periodically investigate the soil’s porosity and its water-ice content, taking advantage of the mobility offered by the rover to map resources along its traverse. As the sensing depth correlates with the electrode’s size, the two electrodes have different dimensions and allow for determining the depth-dependent stratification and stability of water ice in the shallow subsurface.

The back-end electronics board includes circuitry to cycle four different excitation frequencies. For this mission, read-out of the sensor will be performed by the rover’s digital electronics, reducing the complexity and power demand of the sensor electronics.

In between the electrode and the backend electronics, a novel coaxial pancake slip ring is used to transfer the excitation and signal from the static body to the rotating rover wheel. The slip ring was specifically developed to cope with the harsh lunar environment and dust contamination while providing effective shielding for the sensitive measurement signal of the permittivity sensor.

The permittivity measurements are accompanied by measurements of the regolith surface temperature, with both, a contact temperature sensor integrated into one electrode and a thermopile sensor attached to the rover’s body. The sample temperature is a crucial parameter for the soil permittivity; therefore these additional sensors provide important contextual information for data interpretation.

Figure 1: RPS wheel architecture (second electrode obstructe).

Figure 2: Assembled electrode prototype.

Results: In the feasibility study, a fully functional prototype of RPS has been developed and evaluated. Figure 1 conceptually shows the wheel section of the instrument and Figure 2 depicts one of the wheel-mounted sensor electrodes. The results of the feasibility study confirm the measurement concept and the predicted magnitude of geometric capacitance of the novel electrodes. In addition, experiments with the thermopile temperature sensor showed that this concept is also viable for samples at cryogenic temperatures.

Conclusion and Outlook: The recent study has proven the technical feasibility of the RPS concept for lunar exploration. With a newly developed slip ring and two electrodes, mapping of water ice on the lunar surface and investigation of its stratification in the shallow subsurface is possible. A special development effort was put into selecting materials and components suitable for an ongoing development to facilitate a fast progression towards a flight instrument.

At TUM, a specialized dusty thermal vacuum system is being assembled to assess electrode robustness, slip ring dust tolerance, and combined system performance in a representative environment and with icy regolith simulant. Refined and extensive testing of the thermopile sensor is also foreseen as a next step.

In addition to their application on lunar rovers, similar permittivity sensors could also be integrated into other exploration systems, such as penetrators or landers, to provide valuable context information about the soil properties and potential water-ice content.

Acknowledgement: The RPS Feasibility Study was funded by ESA.

References: [1] Trautner, R et al. (2025), Frontiers in Space Technologies, 5 [2] Gscheidle, C. et al. (2022), PSS, 212, 105426 [3] Nurge, M. A. (2012) PSS., 65, 76-82 [4] Trautner, R. et al. (2021) Meas. Sci. Technol, 32, 125117 [5] Gscheidle, C. et al. (2024) Frontiers in Space Technologies, 4 [6] Seidensticker, K. J. et al. (2007) Space Sci. Rev., 128, 301-337 [7] Grard, R. et al. (2006) PSS, 54, 1124-1136 [8] Trautner, R. et al. (2024) Euro. Lunar Symposium, Dumfries, UK

How to cite: Gscheidle, C., Eckert, L., Sesko, R., Trautner, R., and Reiss, P.: Feasibility of a Rover-wheel-based Permittivity Sensor for Prospecting Lunar Water, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-922, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-922, 2025.

Introduction: Methane observed in the Martian atmosphere is not stable on geological timescales, suggesting a source on Mars that is active today [1]. Several theories have been proposed that link this atmospheric methane to emission from ancient subsurface reservoirs (such as methane hydrate clathrates) [2,3], hot water/rock reactions (e.g. Fisher Troph-Type Processes) [4], exogenous input of organic material (e.g. Interplanetary Dust Particles), [5] or biological activity [4]. However, methane is currently measured in the near-surface atmosphere only a few times per year, making testing these theories challenging [6, 7].

Methane on Earth is primarily biological, making the methane cycle on Mars of great astrobiological interest. This instrument could also provide important thermochemical data about the Martian subsurface[1].

Figure 1: The ABB breadboard prototype spectrometer.

Figure 1: The schematic for the experimental breadboard spectrometer.

The Martian Atmospheric Gas Evolution (MAGE) experiment was proposed to provide the data needed to distinguish between different theories of the origin and evolution of methane in the Martian atmosphere. A small gas spectrometer, based around the ABB Integrated Cavity-enhanced Optical Spectroscopy (ICOS), is a Canadian instrument that could be deployed to sample the concentration of atmospheric methane on an hourly basis [3].

Methodology: For this work, we use an experimental ICOS spectrometer which represents a prototype of a future spectrometer capable of flight to Mars. Images of the breadboard instrument (Figure 1) and its schematic (Figure 2are shown. The prototype spectrometer contains 2 lasers, a 1659 nm laser analyzing concentrations of 12CH4 and 13CH4, and a 1650 nm laser analyzing concentrations of 12CH4 and CO2.

The prototype spectrometer’s 1659 nm laser was tested using with a balance gas of carbon dioxide. Mass flow controllers were used to make methane concentrations of 1000 ppmv and 10 ppmv. Tedlar bags were used to make theoretical concentrations of methane of 1 ppmv and 10 ppbv by serial dilution. As there was difficulty obtaining a concentration of methane below 10 ppm due to methane contamination of the CO2 background gas, the runs of 10 ppm, 1 ppm, and 10 ppb are considered equivalent due to background gas contamination. The graphs below show the raw data, processed data with a uniform window filter of size 10 applied, and the data with the drift removed by subtracting the filtered data from the raw data. A mean line goes through the center of the graph. The integration times discussed further in the results section are calculated using the results with the drift removed.

Figure 3: Concentrations of 12CH4 from the prototype spectrometer

Figure 4: Concentrations of 13CH4 from the prototype spectrometer.

Results: As the seasonal background of methane on Mars ranges in concentration from 0.2-0.7 ppbv, with periodic high spikes of up to 45 ppbv [7], sensitivity in this range would make a flight instrument based on ours suitable for the detection of methane. The instrument takes an average of 16 hours of operation to reach 95% confidence that the concentrations of 13CH4 detected are within 1 ppb of the true value, while it takes an average of 56,647 hours to reach 95% confidence that the values of 12CH4 are within 1 ppb of true values. The significant drop in integration time when observing 13CH4 vs 12CH4 is due to a more stable signal response at lower concentrations of gas. The results from the 10 ppm, 1 ppm and 10 ppb runs are averaged to obtain the operational times discussed above, as they are considered replicas. The long measurement time is largely due to instability caused by noise within the instrument, clearly seen in the results for both 12CH4 and 13CH4 (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Future Work: Future modifications include testing under Mars-like conditions, including testing the instrument with Mars analogue mixtures of gases. This will include pressure changes in the atmosphere to observe how the limits of detection change. If deployed on a Mars rover, or on a rotorcraft, the instrument could help to constrain the potential sinks and sources of Martian methane.

Acknowledgments: This work was funded by the Canadian Space Agency FAST program grant No, 19FAYORA13 and is being pursued in collaboration with ABB Inc.

References: [1] Atreya, S. K., Mahaffy, P. R., & Wong, A.‐S. (2007). Planetary Space Science, 55(3), 358–369. [2]Stevens, A. H., Patel, M. R. & Lewis, S. R. Icarus 281, 240–247 (2017). [3] Lasue, J., Quesnel, Y., Langlais, B. & Chassefière, E. Icarus 260, 205–214 (2015). [4] Oehler, D. Z., & Etiope, G. (2017)., 17(12), 1233–1264.1657 [5] Schuerger, A.C., Moores, J., Clausen, C., Barlow, N., Britt, D., 2012. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 117, E08007.. [6] Webster, C. R., Mahaffy, P. R., Atreya, S. K., Moores, J. E., Flesch, G. J., Malespin, C., et al. (2018). Science, 360(6393), 1093–1096. [7] Moores, J.E., Sapers, H.M., Oehler, D., Newman, C. and Whyte, L. (2021) 8 pp. published in Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, Vol 53, issue 4. https://baas.aas.org/pub/2021n4i125/release/1

How to cite: Newton, A., Axelrod, K., Moores, J., and Sapers, H.: Laboratory Evaluation of a Methane Spectrometer for the Martian Atmosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1119, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1119, 2025.

It is common human experience that wind is associated with noise. Acoustic noise is generated by the turbulent pressure fluctuations associated with the shearing flow near the ground. Sound levels recorded on the Venera 13/14 missions at Venus were used to estimate winds (Ksanfomality et al., 1983). More recently, measurements with the SuperCam microphone on the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover have found that the power spectral density at low frequencies correlates well with windspeed (e.g. Maurice et al., 2022; Stott et al., 2023). The rapid response of microphone sensors makes it possible to resolve rather rapid changes in wind conditions, e.g. during dust devil encounters (Murdoch et al., 2022).

Here we show that a simple, inexpensive microphone can yield quantitatively-useful measurements of wind speed in terrestrial field conditions, even when its output is very sparsely-sampled. This is of practical utility in that passive acoustic measurements can be made with extremely low power requirements (unlike ultrasonic or hot film anemometers) and with no moving parts (as do cup or propeller anemometers) making them very useful for long-term field observations. These aspects, and their low geometric volume and cost, make them attractive for sensor networks.

The field measurements were conducted on a dry lake bed about 1 km southwest of the 70m radio telescope at the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex (35°25′36″ N, 116°53′24″ W) outside Barstow, California, operated by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The measurement campaign was initiated by the InSight project, with the intent of acquiring representative seismic data from a shallowly-emplaced seismometer in desert field conditions. In addition to the main equipment installation (seismometer and anemometer), we deployed loggers that recorded pressure and an analog voltage from a user-supplied sensor at 1 sample per second. As an experiment, we connected this measurement channel to an amplified Micro ElectroMechanical System (MEMS) microphone (Analog Devices ADMP401). We have previously shown (Lorenz et al., 2017) that the output from such a microphone can be related, as can that of other simple electret microphones (Chide et al., 2021) to windspeed and direction in a wind tunnel, even at Mars atmospheric density.

The microphone, datalogger, and 2 alkaline D-cell batteries permitting weeks of unattended operation, were mounted in a plastic box set on the playa floor, 60m to the west of the anemometer station. The anemometer recorded at 1 minute intervals. The instrumentation was deployed in May 2015 and retrieved in August. We concentrate our analysis on a 12-day period when good data were acquired.

The microphone record comprises individual instantaneous voltage samples at 1.5-s intervals. The samples are 12-bit integers (0-4095) mapping to the range 0-5 V; the amplifier shifts the zero level to half of the 3.3V supply, thus readings are symmetrically distributed about a base value of ~1667. The signal of interest, then, is the absolute value of the difference between an individual sample and the base level (the latter of which is readily obtained by taking a long-term average).

Figure 1. Left panel is the 12 day period, with the maximum and 2x the mean signal value over 60s-intervals shown as grey lines and red points, respectively. In the lower panel is the 1-minute mean wind (red) and maximum ‘gust’ (grey) recorded by the anemometer. The right panel is the same, but zoomed in on a 24-hr period in the middle of the record.

The dominant signals in the wind noise are at low audio frequencies, and at infrasound frequencies (where the microphone has poor response). But these are still high very frequencies compared with the sample rate of 0.67/s, and thus samples are at random phase. Such ‘snapshots’ of a constant-amplitude monochromatic signal would yield a saddle-shaped histogram, since the system spends more time at the ends of the cycle than at the center. Thus, sparse sampling is quite effective at capturing the amplitude of a signal.

Figure 2. Correlation of microphone signal fluctuation with mean wind speed. Above a speed of 20 m/s, the signal becomes saturated.

It is seen in figure 2 that below a windspeed of ~4 m/s the microphone output is small. Between 4 and 20 m/s (100.6 and 101.3) there is an excellent correlation of the microphone output with wind speed, with the scatter being about +/- 100.1, or about 25% of the actual value. The slope of the correlation in logarithmic space is ~1.6. This is close to the exponent of 2.0 that one would expect if pressure fluctuations were proportional to the dynamic pressure, i.e. mean velocity squared.

The microphone datasheet (Analog, 2012) indicates a -3dB low-pass sensitivity limit of 60 Hz and -10dB at 20 Hz. There is additional high-pass filtering (22 Hz corner frequency) in the amplifier. Thus in practical terms the wind sensitivity arises as a compromise between the larger pressure fluctuations at low frequencies, and the higher device sensitivity towards higher frequencies. One could contemplate improving sensitivity by associating the device with a smaller structure (or even introducing specific resonant geometries, like an organ pipe) to develop higher-frequency pressure fluctuations for a given flow speed. In any case, the ‘calibration’ of this type of measurement is rather device-dependent and mounting-dependent.

A simple microphone signal, even grossly undersampled, can yield a wind estimate over a useful range of speeds. It is easy to imagine that some simple analog signal-processing (e.g. a low-pass filter and envelope detector) could yield a better wind speed estimate than the statistics from random instantaneous voltage samples we have presented ; similarly, digital signal processing could be readily implemented. It seems likely that such an approach could yield wind estimation on sub-second timescales, without requiring large data volumes to be stored or telemetered : data volume is an important constraint on remote monitoring stations, especially those on planetary bodies. This work will inform the sampling strategy to be used on the microphones on the Dragonfly mission (Lucas et al., 2024).

How to cite: Lorenz, R., Chide, B., Stott, A., and Murdoch, N.: Under-Sampled Microphone Data as a Wind Measurement, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1137, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1137, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Title : Ion and Neutral Energy and Mass Analyzer for M-MATISSE

Anthony PINEY (anthony.piney@latmos.ipsl.fr)1, François LEBLANC1, Jean-Jacques BERTHELIER1, Valentin Steichen2,1, Gabriel GUIGNAN1, Frédéric FERREIRA1, Cosima DORLAND1, Christophe MONTARRON1, Laurent LAPAUW1, Ronan MODOLO1, Quentin NENON1 and Jean-Yves CHAUFRAY1.

1 LATMOS/CNRS, Sorbonne Université, UVSQ, France

2 SwRI, San Antonio, USA

Mars Ion and Neutral Mass and Energy Analyzer (M-INEA) is an instrument selected for the mission M-MATISSE (PI: B. Sanchez-Cano, University of Leicester, UK) proposed in the frame of the ESA M7 call and, at present, in a competitive phase A (2024-2026). M-MATISSE is a project with two spacecrafts around Mars dedicated to the characterization of Mars’ environment from its induced magnetosphere down to its lower atmosphere combining in situ with remote observations. One of the goals of M-MATISSE will be to characterize the composition, density, wind and temperature in the upper thermosphere/ionosphere of Mars, as well as its atmospheric escaping rate. A two points measurements strategy will allow M-MATISSE to distinguish between time and spatial variabilities and to follow solar events encountering Mars from the solar wind down to Mars’ surface.

M-INEA is an instrument developed and tested at LATMOS. It is part of the M-MATISSE payload and is dedicated to the measurement of the density, composition, wind and temperature of the Martian thermosphere and to the measurement of the atmospheric escape and its dependence on the solar conditions. The main target of M-INEA is to measure the energy distribution function (density, temperature and drift velocity along the axis of sight of the instrument, see Fig 1). The instrument is based on an original electrostatic design specially designed to achieve an energy resolution better than 0.1 eV over an energy range of 0-10 eV, as well as a temperature resolution better than 50 K with high sensitivity and mass resolution of the order of 20. Such performances are also possible thanks to the use of an original ion source using carbon nano-tubes for the emission of electrons.

The mechanical and electronic designs of the instrument are being done as well as first tests demonstrating M-INEA's performances as well. We will present the state of design and tests of M-INEA during this presentation.

Figure 1: schematics of M-INEA with particles trajectories.

How to cite: piney, A., leblanc, F., and berthelier, J.: Ion and Neutral Energy and Mass Analyzer for M-MATISSE, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-107, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-107, 2025.

The boulder shape at the surface of small bodies enables the investigation of the geological processes the surface boulders have undergone, and the estimation of certain mechanical properties (e.g. [1]). Studies conducted on surface boulders observed on extraterrestrial planetary bodies are usually performed using 2D images of the projected surface [1, 2, 3, 4]. 2D projections of irregular particle are known to differ from their 3D geometry [5, 6, 7], therefore, careful precautions are required when comparing different surfaces and, in particular, different representations (2D or 3D).

To investigate how representative 2D images of boulders are for estimating bulk 3D morphological parameters, three different granular samples (LHS-1 Lunar Highland Simulant, Øysand soil, and glass grit) were scanned by XCT (X-ray Computed Tomography) to reconstruct the 3D geometry of each particle. The shapes of more than 2500 particles have been analyzed using both the 3D geometry and different 2D projections from the 3D reconstruction. The 2D shape analysis pipeline used in this study was previously applied in Robin et al. (2024) [1] and Kohout et al. (2024) [8]. A 3D shape analysis has been extended using the same methodology as the 2D analysis.

The shape can be expressed using three independent descriptors based on the observation scale [9, 10]: the form (large scale), roundness (intermediate scale), and surface texture (small scale). The morphological parameters measured in this study include axes ratios and sphericity (large-scale measurements), and roundness. In addition to the shape analysis, the size of particles is also computed (fig. 1).

Figure 1: Definitions of size and shape descriptors measured for 2D (left) and 3D (right) representations.

Using the 2D and 3D morphological analysis of the XCT scan dataset, correlation formulas with confidence intervals have been established between both representations to estimate 3D morphological parameters from 2D measurements.

Our methodology to estimate 3D parameters from 2D measurements is being tested with boulders observed on asteroid Bennu by the NASA OSIRIS-REx mission (fig. 2). Boulders on Bennu have been observed by different instruments; in 2D by OCAMS (OSIRIS-REx Camera Suite) [11], and in 3D by OLA (OSIRIS-REx Laser Altimeter) [12]. The results of the comparison between the estimated 3D parameters obtained with the 2D images and the 3D analysis from the same boulders observed with OLA will be presented during the conference in addition to the analysis of XCT scan data.

Figure 2: An example of boulders observed on asteroid Bennu by different instruments during the NASA OSIRIS-REx mission. OLA measurements (left) provide the surface topography (3D), and the same surface has also been observed in 2D with OCAMS (right). (Credit: NASA/Goddard/University Of Arizona)

References

[1] Robin, et al. (2024). Mechanical properties of rubble pile asteroids (Dimorphos, Itokawa, Ryugu, and Bennu) through surface boulder morphological analysis. Nature communications, 15: 6203.

[2] Yingst, et al. (2007). Quantitative morphology of rocks at the Mars Pathfinder landing site. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 112.

[3] Cambianica, et al. (2019). Quantitative analysis of isolated boulder fields on comet 67P/ Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 630:15.

[4] Jawin, et al. (2023). Boulder Diversity in the Nightingale Region of Asteroid (101955) Bennu and Predictions for Physical Properties of the OSIRIS-REx Sample. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 128:12.

[5] Jia et al. (2023). Sphericity and roundness for three-dimensional high explosive particles by computational geometry. Computational Particle Mechanics, 10:817-836.

[6] Beemer, et al. (2022). Comparison of 2D Optical Imaging and 3D Microtomography Shape Measurements of a Coastal Bioclastic Calcareous Sand. Journal of Imaging, 8:72.

[7] Zheng, et al. (2021). Three-dimensional Wadell roundness for particle angularity characterization of granular soils. Acta Geotechnica, 16:133-149.

[8] Kohout, et al. (2024). Impact Disruption of Bjurböle Porous Chondritic Projectile. The Planetary Science Journal, 5:128.

[9] Barrett (1980). The shape of rock particles, a critical review. Sedimentology, 27:3.

[10] Cho, et al. (2006). Particle Shape Effects on Packing Density, Stiffness, and Strength: Natural and Crushed Sands. Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 132:5.

[11] Rizk, et al. (2018). OCAMS: The OSIRIS-REx Camera Suite. Space Science Reviews, 214:26.

[12] Daly, et al. (2017). The OSIRIS-REx Laser Altimeter (OLA) Investigation and Instrument. Space Science Reviews, 212:899-924.

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement N°870377 (project NEO-MAPP), and CNES in the framework of the Hera mission and the MMX rover/wheelcams. A.D. acknowledges PhD funding from Université de Toulouse III. C.R. acknowledges PhD funding from CNES and ISAE SUPAERO. O. S. Barnouin’s and R. L. Ballouz’s efforts were funded by the NASA New Frontier Data Analysis Program under grand number 80NSSC22K1035 P00004.

How to cite: Duchêne, A., Murdoch, N., Robin, C., Mikesell, T. D., Barnouin, O. S., Ballouz, R. L., and Jerves, A. X.: Boulder shape analysis: is a 2D projection reliable for capturing the 3D geometry?, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-114, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-114, 2025.

I. INTRODUCTION

The Chandrayaan 3 (C3) mission was developed and launched by the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) in July 2023. After the failure of Chandrayaan 2 lander in 2019, the goal of Chandrayaan 3 was to achieve the objectives of its predecessor, i.e., demonstrate full capability in safe landing, roving, and conducting in situ experiments on the lunar surface. This mission contained a lander including a 26-kg rover named Pragyan that carried the Low-energy Eye-safe Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LE-LIBS) instrument. The laser operates at 1540 nm, delivering 20 pulses at 5 Hz, with an energy between 3 and 4 mJ per pulse on target.

During its 100-meter traverse (Fig. 1), the rover conducted 66 LIBS investigations. At each of those locations, there are between 1 and 10 LIBS spectra. The results have been studied in this work and compared with the preliminary results of Sridhar et al., (2025) [1].

Fig. 1: Path of Pragyan rover (from ISRO).

II. DATA PROCESSING

The C3 archive [5] contains both raw data (level-0) and wavelength-calibrated data (level-1). Starting from level-0 data, we built our own calibration. Data were first de-noised with the Undecimated Wavelet Transform method (UWT) [3], followed by baseline removal with Asymmetrically Iterative Reweighted Penalized Least Squares (AIRPLS) function [4]. We found that our results do not match level-1 data provided by the C3 team [5] with unexplained discrepancies up to 8 nm. Thus, for the rest of the study, we used our own calibration, starting from level-0 data.

Next, emission peaks were fitted with a Lorentzian function that led to peak identification and resolution from wavelength and full width at half-maximum (FWHM), respectively. The NIST database was used for peak element identification.

III. RESULTS

We have processed all 66 investigations, and when significant, classified the results (see Fig. 2 below) on the basis of Signal to Noise Ratios (SNR) and noise levels. We then focused on Target 6 to compare our element identification results with those reported in [1], and subsequently with Target 19.

A. Spectra classification

We have developed a Python tool to process 34 of the 66 operations, which are considered by the C3 team as significant for science, resulting in 170 LIBS spectra Those spectra were compared and classified based on their main characteristics, i.e., noise and SNR. SNR is defined as the ratio of the maximum peak amplitude versus the standard deviation of the signal between 680-760 nm, a zone considered as pure noise. With this information, we found that 13 of the 66 investigations have the best signal with the most peaks (tens to hundreds of peaks as expected in LIBS spectra [2]) and are therefore scientifically usable.

Fig 2: Operations classification regarding the noise and the SNR of the strongest peak. Data from operations 14, 21, 22, 23, 24, and 47 are damaged and not shown. The 13 optimal investigations are circled in red.

B. Comparison with Sridhar et al., (2025) [1]

Target 6 reported in Sridhar et al., (2025) [1], was acquired on August 27, 2023 at 18:12.23 UT. Figure 3 shows our processing of the LIBS spectrum, which we compared with the one processed by the C3 team.

Both spectra appear similar, but differences arise after removing the baseline and fitting the peaks. The same number of peaks could be fitted in both of the studies, however, our element identification based on NIST database do not fully agree with the results in [1].

We have identified 28 peaks. 11 match in wavelength and element identification results of [1]. We found that 17 do not match in wavelength (i.e., shifted by more than 1 nm). Specifically, 6 do not match in element identification because another element is more probable while the other 11 do not have an unequivocal element candidate. This means those peaks do not match regarding the element in the NIST database, or the presence of the element is in doubt because the major emission peaks of this element are missing (e.g., manganese, chromium, titanium). Finally, some elements like silicon, iron and aluminum are clearly present in this sample, but among the few peaks attributed to those elements some do not include the most intense peaks like the one attributed to Si I at 792 nm. Our wavelength recalibration did not change these observations.

Fig. 3: Spectrum of Target 6 derived in this work. Some peaks could not be associated with specific elements, as no unequivocal correspondence using NIST could be established.

C. Comparison with Target 19

The measurements of target 19 took place 2 days after Target 6, and their spectra are both clean and strong (Fig. 2). Thus, the comparison can remove doubt and confirm peak wavelengths. It appears that the spectra of these targets are very similar, which confirms that the same regolith was sampled in both cases. We will continue to investigate other targets to confirm the presence of additional elements beyond Fe, Al, Mg, Ca, O, and Si.

IV. CONCLUSION

Chandrayaan-3 has demonstrated that LIBS can work on the Moon, despite challenges with the current setup (no active refocus) to systematically acquire a meaningful signal. One of the next steps is to investigate the origin of the observed nonlinear wavelength shifts. A possible explanation is an issue with the beam focus, which we are currently investigating in our laboratory.

REFERENCES

[1] Sridhar, R. V. L. N., et al. « Chandrayaan-3 LIBS Sensor: Preflight Characterization, Inflight Operations, and Preliminary Observations ». IEEE Sensors Journal 25, no 2 (2025): 2554‑66. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3506037.

[2] Wiens, Roger C., Sylvestre Maurice, et al. « The SuperCam Instrument Suite on the NASA Mars 2020 Rover: Body Unit and Combined System Tests ». Space Science Reviews 217, no 1 (2021): 4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-020-00777-5.

[3] Starck, Jean-Luc, et al. « The Undecimated Wavelet Decomposition and its Reconstruction ». IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 16, no 2 (2007): 297‑309. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2006.887733.

[4] Baek, Sung-June, et al. « Baseline Correction Using Asymmetrically Reweighted Penalized Least Squares Smoothing ». The Analyst 140, no 1 (2015): 250‑57. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4AN01061B.

[5] pradan.issdc.gov.in/ch3/

How to cite: Mourlin, F., Rapin, W., Maurice, S., Lasue, J., Forni, O., Cousin, A., and Meslin, P.-Y.: Chandrayaan 3 data: Unveiling the challenges of performing LIBS on the Lunar Surface, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-704, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-704, 2025.

The MOlecular Beam for Instrument Utilization and Simulation (MOBIUS) is a newly developed calibration facility at Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) designed to test and calibrate in-situ neutral mass spectrometers. MOBIUS was built to calibrate Strofio, the neutral mass spectrometer on the BepiColombo mission, by replicating the conditions it will encounter while orbiting Mercury at 3 km/s. To achieve the necessary calibration conditions, MOBIUS generates a high-speed neutral beam using a silicon carbide nozzle capable of withstanding extreme temperatures (~2000°C) and pressures (~30 bar). While tailored for Strofio, the facility is versatile and can accommodate the calibration of other neutral mass spectrometers requiring beam speeds of up to 8 km/s. This presentation will introduce MOBIUS, detailing its design, capabilities, and potential applications for future space instrument testing.

How to cite: Schroeder, J., Livi, S., Patrick, E., Steichen, V., and Turner, J.: A New Molecular Beam Facility for In-Situ Neutral Mass Spectrometer Calibration, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-785, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-785, 2025.

On 14 April 2023, the JUICE spacecraft was launched to the Jovian system to study the emergence of potentially habitable worlds around gas giants. The Neutral-Ion Mass Spectrometer (NIM), developed by the University of Bern, will characterise the atmospheres of the Galilean moons and analyse subsurface material ejected by Europa’s plumes. NIM uses a power-efficient hot cathode filament which creates an electron beam to ionize atoms and molecules for mass spectrometric analysis.

For this mission, we employ customized yttrium oxide (Y2O3) cathodes produced by Kimball Physics, based on the ES-525 design. For example the filament legs are lengthened to minimize heat loss through conduction. Additionally, a thicker coating is applied to enhance longevity. Given the criticality of correct cathode operation, two cold-redundant cathodes are installed in the NIM instrument.

This study compares the performance of the space-qualified cathodes in the Proto Flight Model (PFM) instrument, post-launch (in orbit) commissioning, with both expected performance metrics and laboratory-tested cathodes in the Flight Spare (FS) instrument.

During commissioning, the PFM cathodes underwent conditioning lasting several hours. While both cathodes were successfully conditioned, cathode 2 exhibited performance comparable to FS cathodes, whereas cathode 1 deviated from the pre-flight performance. This deviation was further investigated through additional investigations and tests. Preliminary findings suggest that launch-induced vibrations caused slight bending of the cathode legs, resulting in asymmetry between the emitting disk and the surrounding repeller electrode.

The cathodes operate within a nominal emission range of 100 to 300 μA. Without active beam shaping, power consumption varies between 1.2 and 1.6 W (up to 1.8 W for the deviating PFM cathode 1) with a current draw of 860 to 980 mA (up to 1030 mA). Optimal beam shaping increases the current requirement by approximately 20 mA. Despite limited available data, we successfully fit our measurements to the Richardson-Dushman equation, describing the relation between operation parameters and emission current, enabling a comparison with theoretical emission expectations.

The heating current drawn by the cathode is expected to increase over the long term (up to a lifetime of 10 000 operational hours) due to degradation of the coating. In contrast, short-term behaviour (up to 100 hours) reveals a "learning" effect: cathodes exhibit improved performance when used under specific active beam-shaping configurations, an effect disrupted after exposure to air.

During the post-launch commissioning of the cathodes in orbit, the LV subsystem was commissioned as well. The commissioning, including the cathodes, bake-out heater, low-voltage electrodes, as well as the necessary electronics was successful. Long-term monitoring of the cathodes' performance in both laboratory and space environments continues.

How to cite: Wyler, S. S., Fausch, R., Vorburger, A., and Wurz, P.: Post Launch Performance of a Hot Cathode for Electron Ionization of a Space BorneTime-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer (NIM on board JUICE), EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-870, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-870, 2025.

Introduction: With the possible return of mankind to the Moon comes the need for detailed analyses of ambient conditions in possible landing regions. Several missions (e.g. IM-2, Blue Ghost M1) have already landed in the Moon’s south pole region to study the environmental conditions, and more are planned. Of particular interest are temperature measurements as they can be used to draw conclusions about the material properties of the regolith such as the surface roughness or the thermal inertia. However, any lander affects the temperature of the ground around it. This effect is particularly strong in the polar regions. Here, the ground is hit by sunlight at a large angle, while for the sides of the lander the incidence angle can be very small. Consequently, a relatively large amount of light can be scattered from the lander to the ground increasing the temperature there. Furthermore, the lander may heat up more strongly, which (depending on the emissivity of the lander's surface) could lead to comparatively large thermal emissions. This study investigates the temperature change caused by a lander located at a latitude of -84.7715° and a longitude of 29.21994°, close to the landing site of Intuitive Machines' IM-2 mission.

Methods: The lander is modeled as a cube with a side length of 1m. To disentangle the influence of the lander from the influence of the local topography, the lander's neighborhood is modeled by a plane. Both the cube and the plane are modelled using triangular meshes with side lengths of 50 cm and 12.5 cm, respectively. We assume that the lander's surface is either covered by black paint (solar albedo 0.04, IR emissivity 0.88) or by Multi-layer Insulation (MLI, solar albedo 0.95, IR emissivity 0.05). For the sake of simplicity we assume, for now, that the lander has a constant temperature of 250 K. With regard to the material properties of the ground we adopt the values of the Oxford Thermal Model [1], except for the solar albedo, which we assume to be constant at 0.12. Regarding scattered light we currently consider only single-scattering. First the surface temperature of the undisturbed plane is determined for epoch 2025-03-07T12:00:00 UTC. On this date the lander is placed on the surface. For all subsequent times the ground temperature is computed taking the lander's presence into account.

Results: Figures 1-4 show temperature curves for a location about 33 cm in front of the lander, where the corresponding lander side is directed to the North. The black curve shows the temperature without the lander, the orange curve shows the temperature when single-scattering and the red curve when single-scattering and thermal emission from the lander are taken into account. Figure 1 compares the temperature curves during one month for a lander whose surface consists of black paint. Due to the low albedo, single scattering only increases the temperature of the ground by a maximum of 7K. The thermal emissions from the lander, on the other hand, increase the temperature of the ground by up to 25 K. At the same time, the ground does not cool down as much during the night as it would without the lander's presence. Figure 2 provides a closer look at the first two hours after landing and demonstrates that the ground responds quickly to the lander's presence.

Figure 3 shows the temperature curves over the course of one month for a lander whose surface consists of MLI. Due to the lander's large albedo, single scattering increases the temperature of the ground by up to 90 K. However, due to the lander's small emissivity, thermal emissions from the lander are negligible during the daytime. At night, they prevent the ground from cooling down as much as it would without the lander. Again, Figure 4 shows the first two hours after landing in more detail.

Figure 1: The temperature at the North side of the lander at a distance of 33 cm for a lander covered with black paint. Black: Temperature without the lander's presence. Yellow: Single-scattering included. Red curve: Single-scattering and thermal emissions included. Before the arrival of the lander at around 8:25 am local time, the three curves are identical. Around 2 pm an eclipse occurs.

Figure 2: The temperature at the North side of the lander at a distance of 33 cm for the first two hours after the landing. For an explanation of the color code see Figure 1.

Figure 3: The temperature at the North side of the lander at a distance of 33 cm for a lander covered with MLI. For an explanation of the color code see Figure 1. Before the arrival of the lander at around 8:25 am local time, the three curves are identical. During daytime the orange and the red curve are identical, too. Around 2 pm an eclipse occurs.

Figure 4: The temperature at the North side of the lander at a distance of 33 cm for the first two hours after the landing. For an explanation of the color code see Figure 1.

Summary and Outlook: If the temperature of the regolith is measured, the presence of the lander must be taken into account, especially if conclusions are to be drawn about the material properties from the temperature.

The next steps are to increase the resolution of the meshes and run our code in multi-scattering mode. Moreover, the lander's temperature will be calculated more accurately. We also plan to study a landing site at the Shackleton - de Gerlache ridge and the case of a lander situated inside a permanently shadowed region.

Acknowledgements: LRAD is supported by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action on the basis of a decision by the German Bundestag. Grant: 50OW2103

References: [1] King et al. (2020), PSS 182. doi:10.1016/j.pss.2019.104790

How to cite: Ziese, R., Knollenberg, J., Hamm, M., Grott, M., and Rauer, H.: The influence of a lunar lander on the temperature of the surrounding surface, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1398, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1398, 2025.

Introduction

In the last decade planetary science has seen an emergence of in-situ, i.e. rover-based, radar subsurface investigation missions on planetary bodies, such as Chang'E 3 and 4 on the Moon as well as the Radar Imager for Mars’ Subsurface Experiment (RIMFAX). Commonly, the geologic stratification and material composition shall be determined, including special targets such as water ice or cavities.

In the meantime, the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and ESA have provided favorable testing conditions through the lunar analogue facility (LUNA), a site that allows human and robotic training in a Moon-like setting [Casini 2020]. The LUNA site features a large-scale pit with a deep (3.0 m) and shallow section (0.6 m), filled with the well characterized EAC-1A lunar regolith simulant. The pit naturally represents a test laboratory for shallow geophysical exploration techniques such as GPR and their inclusion in in-situ planetary exploration campaigns [Knapmeyer 2025].

We employ techniques commonly used on planetary in-situ radar missions. However, without ground-truth information in space it is difficult to disambiguate findings, in particular high-resolution observations such as small target detection and local material parameters estimation. On the contrary, LUNA is both well characterized and proficiently Moon-like, allowing us to validate these methods in conjunction with new instruments.

Figure 1: Left: LUNA hall at arrival. Middle: Buried target sites before regolith infill. Operators need to wear protective gear in the LUNA hall. Right: Example of buried boulder target

Figure 2: Left: Suspended antenna in a low height mode over buried targets. Right: Rover-based radar deployment

Measurements

The campaign of November 2024 focused on the shallow area of 0.6 m depth since the deep area was still subject to filling. Various structures were emplaced into the regolith that model possible targets inspired by Mars and Moon studies [e.g. Casademont 2023]. The targets are comprised of three buried boulders in the depths deep, shallow and surface, a micro impact crater, a duricrust patch, a buried cavity, air-targets, that is targets above ground, both in-drive and out-of-plane as well as a metal plate at maximum depth for reference. Fig. 1 and 2 show the measurement context.

The radar electronics are a Technical University of Dresden built IQ LFMCW 0.3 – 6 GHz full-polarimetric radar. Different antennas have been employed in different heights, with and without targets, with targets in nadir and out-of-plane direction. A precursor campaign sounded the LUNA hall without regolith infill in a similar manner. The set of antennas include a crane-suspended dipol antenna as in Fig 1. and theWater Ice Subsurface Deposit Observation on Mars (WISDOM) antenna deployed directly on the ground [Benedix 2024]. Horizontal and Vertical polarization have been switched for forward and backward traverse along the same measurement path.

Together with the radar elements a set of secondary sensors was deployed. It contained an ultrasound positioning system (MarvelMind), a stereo depth imaging camera pointed in nadir direction for the suspended antenna setup (Orbbec Astra) and a Lidar (R2000) in the x-y plane. Depth camera and Lidar are employed to characterize the site with a high-resolution digital elevation model for subsequent surface clutter estimation. Apart from measurement geometry, the important ground-truth are laboratory dielectric parameters of the EAC-1A substrate. They were previously characterized at room temperature and uncompacted (rho=1.72 g/cm3) for frequencies above 400 MHz by [Ramos Somolinos 2022]. The authors report ε′ = −0.0432f + 4.0397 and tan δe = −0.0015f + 0.0659 (linear fitting). While they describe non-magnetic behavior of EAC-1A, a handheld magnet attracted significant amount of EAC-1A during this campaign. Nonetheless, their characterization serves as temporary ground-truth material parameters until further research is conducted. Volumetric water content sensors installed shortly after the campaign show values 2-5% for the top 4 cm of regolith.

First results

Standard minimal processing includes data curation (sounding localization, repetitive measurement removal, homogenization of sensor clocks, healing of bin-shifts in recording), a windowed Fourier Transform along the soundings and a moving average subtraction to remove the constant background component. Given the rich experimental setup, we focus here on a first assessment regarding target detection.

Fig 3. shows data of the profile where the antenna was suspended with 0.45 m ground clearance at profile start. In the upper subplot, hyperbolic structures can be observed, that are typically associated with localized targets of small extent compared to the wavelength. They mostly coincide with known target positions, for instance the buried reflector target at 2.5m, 28 ns as well as the surfacing targets and air-targets from the micro crater onwards to the right. Hyperbolic signatures are also present around the buried boulder positions, yet their identification is not without ambiguity in standard processing. Surface effects introduce a high degree of hyperbolic scattering

The phase image shows a horizontally undulating band of lower phase variation, which coincides in traveltime with the concrete floor of the LUNA area. Note that the concrete layer flatness will be overprinted with the undulating depth of the regolith infill.

Figure 3: Standard processing, feedpoint time around 18 ns. Top: real part of signal with short term background removal. Bottom: IQ-phase of signal with global BGR

Discussion & Outlook

The experiments show promising results with respect to detectability of typical planetary targets. Tehy also shows that detection of buried targets, especially with respect to hyperbolic permittivity derivation or specific target identification, cannot be considered a trivial task, even under controlled circumstances. Radar instruments need to be fine-tuned and possibly secondary sensors integrated for surface clutter characterization.

References

Casini et al., 2020, Lunar analogue facilities development at EAC: the LUNA project, 10.1016/j.jsse.2020.05.002

Knapmeyer et al., 2025, First campaigns and future developments in the LUNA Moon analog facility, 10.5194/egusphere-egu25-19008

Casademont et al., 2023, RIMFAX Ground Penetrating Radar Reveals Dielectric Permittivity and Rock Density of Shallow Martian Subsurface, 10.1029/2022JE007598

Benedix et al., 2024, The ExoMars 2028 WISDOM antenna assembly: Description and characterization, 10.1016/j.pss.2024.105995

Ramos Somolinos et al., 2024, Electromagnetic Characterization of EAC-1A and JSC-2A Lunar Regolith Simulants

How to cite: Casademont, T. M., Benedix, W.-S., Seeling, J., Laabs, M., Geissler, F., Lu, Y., Knapmeyer-Endrun, B., Fantinati, C., and Plettemeier, D.: Testing of ground penetrating radar at the lunar analog facility (LUNA): A robust reference frame for planetary subsurface exploration, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1718, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1718, 2025.

NASA is preparing to launch the Dragonfly mission, a rotorcraft lander destined for the surface of Saturn’s moon Titan [1]. As part of this mission, the entry vehicle will carry the Dragonfly Entry Aerosciences Measurements (DrEAM) payload [2], which includes a sensor suite known as the COmbined Sensor System for Titan Atmosphere (COSSTA). This instrumentation package is being co-developed by NASA and the Supersonic and Hypersonic Technologies Department at the DLR Institute of Aerodynamics and Flow Technology. One component of COSSTA is a low-pressure sensor, COSSTA-PL, developed by the Finnish Meteorological Institute (FMI) to capture static pressure data on the backshell of the entry capsule.

COSSTA-PL builds on FMI’s experience with Mars missions, closely following the design of previous pressure sensors such as MEDA PS on the Perseverance rover [3]. FMI has pressure calibration facilities specifically developed for the low-pressure range characteristic of Mars’ surface conditions, as well as the pressures expected in the upper atmosphere of Titan during the beginning of entry. The sensor is calibrated at FMI’s facilities over a pressure range of 0 to 20 hPa and a temperature range of -70 to +55 °C. Since the sensor may be exposed to extremely cold temperatures in the backshell, additional calibration measurements down to -150 °C are also performed at COSSTA level.

References

[1] Lorenz, R. D. et al. (2018). Dragonfly: A Rotorcraft Lander Concept for Scientific Exploration at Titan, Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest 34(3), pp. 374-387.

[2] Brandis, A. et al. (2022). Summary of Dragonfly’s Aerothermal Design and DrEAM Instrumentation Suite, 9th International Workshop on Radiation of High Temperature Gases for Space Missions, 12 – 16 Sep 2022, Santa Maria, Azores, Portugal.

[3] Jaakonaho, I. et al. (2023). Pressure sensor for the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover, Planetary and Space Science 239, 105815, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2023.105815.

How to cite: Jaakonaho, I., Hieta, M., Genzer, M., Polkko, J., Thiele, T., Harri, A.-M., and Gülhan, A.: Calibration of COSSTA-PL low-pressure sensor of the Dragonfly entry capsule, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1721, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1721, 2025.